Microposaurus

Microposaurus (meaning "small eyed lizard"; from Greek μικρός, "small" + ὀπός, "face" or "eye" + σαῦρος, "lizard") is an extinct genus of trematosaurid temnospondyl. Fossils are known from the Cynognathus Assemblage Zone of the Beaufort Group (part of the Karoo Supergroup) in South Africa and the Rouse Hill Siltstone of Australia that date back to the Anisian stage of the Middle Triassic.[1][2] These aquatic creatures were the short snouted lineage from Trematosaurinae.[1]

| Microposaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

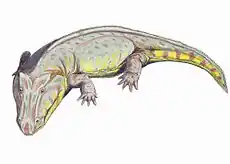

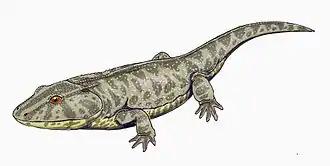

| Life restoration of Microposaurus averyi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Temnospondyli |

| Suborder: | †Stereospondyli |

| Family: | †Trematosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Trematosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Microposaurus Haughton, 1925 |

| Species | |

| |

Discovery

During 1923, the first species of Microposaurus were found by Dr. E. C. Case on a venture into the redbed exposures of Wonderboom Bridge.[3][4] These sites, just south of Burgersdrop Formation in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, were from the Cynognathus zone.[4] When found, the skull was described as an “embedded palate upwards, in a fairly soft dark-green shaly mudstone” which is characteristic of the amphibious behavior of Microposaurus.[4] Relating to the name of the discoverer, the given name was Microposaurus casei. Unfortunately, the skull had a ferruginous material coating that could not be removed without damaging the already crushed skull.[4] Also, from the coating, the sutures typical of skulls were unable to be determined decisively.[4] From these drawbacks, many features stated by Haughton in his first examination of the specimen were later determined to be incorrect. As a result, when Damiani wrote his paper on M. casei he noted many features that Haughton had named or described incorrectly.[1]

Several decades later, a new Microposaurus species was uncovered. During an expedition in the Anisian Rouse Hill Siltstones, Steven Averyi found and named the holotype and single specimen of Microposaurus averyi.[2] Unlike M. casei, this specimen was found in the Ashfield Shale Formation of New South Wales, Australia.[5] Quite a distance from South Africa, the environment during the life period of Microposaurus would have been similar in both cases. The marine landscape, with black/gray, silty claystone was indicative that M. averyi also lived an amphibious lifestyle.[5]

Classification and species

The classification of the first discovered skull of Microposaurus were to the lineage of trematosaurines. Common trematosaurines features observed from the specimen were their orbits were within the anterior half of their skull, the postorbital-prepineal growth zone was present, the anterior palatal vacuities were paired, the transvomerine tooth row was reduced or absent, the parasphenoid was antero-posteriorly elongated, the exoccipitals were underplated by the parasphenoid being posteriorly expanded, and in adults the orbits were small and located near the lateral margins of the skull.[1] Based on these characteristics many authors agreed on the evolutionary placement of these amphibians.[1] Furthermore, one main aspect of M. casei provided evidence for branching off from their sister family Lonchorhynchinae. The physically striking contrast between Microposaurus and Lonchorhynchinae was their seemingly short snouts compared to the elongated counterpart of the latter.[1]

Description

Skull

Besides being narrow, long, and wedge-shaped like most trematosaurids, M. casei also had significant ossification that caused individual skull bones to be indistinguishable from fusion with one another.[1] A notable characteristic was the posterior placement of the “suspensorium beyond the skull table”.[1]

The rounded tip of their short snout produced nostrils that were closely spaced and further back which was from a significant prenarial growth.[1] Furthermore, the nostrils had a teardrop shape from the anterior constriction experienced at the snout.[1] An attribute of M. casei was symphyseal tusks from their lower jaw protruding into the nostril openings that caused small foramens in the anterior palatal vacuities to ventrally open with the nostrils (dorsally).[1]

Found in all trematosauroids, their orbits were elliptical (long axes oriented medially) and had a smooth dorsal surface to the palatines.[1] Upon this surface is also multiple foramina.[1] Described as being more-complete on the left side of the skull and “relatively large, elliptical, and slightly constricted posteriorly”. This is unique when compared to other trematosaurids having shallow and triangular otic notches.[1]

Palate

As in the skull, the palate was also heavily ossified with a similarity to their lineage with having paired anterior palatal vacuities (APV).[1] These APVs were formed by the premaxillae (anteriorly) and the vomers (posteriorly).[1] These APVs had a posteroventrally prong-like process that separated them from one another anteriorly.[1] Another similarity was the choana which is larger in Microposaurus but still circular-elliptical in appearance.[1] A lasting ancestral trait was the quadrate ramus's primitive appearance of the same length and orientation.[1] Some differences were the parasphenoid and pterygoid sutures were elongated, and the “parasphenoid was broader posteriorly than anteriorly”.[1]

Dentition

Out of any stereospondyl, the dentition of M. casei was described as the most specialized.[1] The marginal tooth row were recurved medially which is a characteristic of mastodonsauroids and not trematosauroids.[1] However, the tightly packed marginal teeth all had plaurodont implantations with antero-posterior compression at the bases.[1] The palatal tooth row were reduced with little teeth on the vomers (medial to the choana) and on the posterior ends of the ectopterygoids.[1] There were no teeth on the palatines.[1] Referring back to the anterior tusks, they were giant in size with the left vomer being about 50mm in height, and the smallest on the left ectopterygoids at 30mm in height.[1] The acrodont tooth style was seen in the palatal teeth and the tusks.[1]

Occiput

Exoccipital condyles were present with a large, rounded outlining.[1] The paroccipital processes were attached to each condyle but barely persevered in the specimen.[1] A single, large paraquadrate foramen was seen near the posterolateral margin of the skull.[1]

M. averyi

Three distinctive characteristics were detected on the M. averyi specimen that separated the two species from one another. The greatly enlarged anterior emargination of the external nostrils were more anteriorly placed.[2] The APV were widely separated without the prong of the premaxilla like M. casei. And there was a medial subrostral fossa in the premaxillae.[2]

Geological and Paleobiology

While Microposaurus lived during the Anisian period of the Triassic, the transition from the Permian-Triassic created more aquatic environments for these species to survive. In the Karoo Basin of South Africa, after the extinction, multiple new rivers were created that ran through areas of the continent.[6]

Due to the aquatic lifestyle of Microposaurus, their diet was determined to be piscivorous.[7] For all trematosaurids, most were marine at one point in their life cycles.[7] The normal size of these carnivorous predators was about one to two meters in total body length.[8] Inferred to be eating smaller vertebrates found in their wide range of environments.

At the time of diverging of trematosaurids (between the short and long-snouted (Lonchorhynchinae)), these aquatic swimmers had a nearly global distribution.[8][2] The contribution to this wide distribution is from their possible euryhaline ability and preference to “nearshore marine to distal deltaic habitats”.[9][10] These observations were “based on the associated invertebrate faunal elements such as ammonoids and bivalves”.[9] Alternatively, marine temnospondyls were interpreted as “‘crisis progenitors’” who were “‘initially adapted to perturbed environmental conditions of the mass extinction interval, readily survive this interval, and are among the first groups to seed subsequent radiation into unoccupied ecospace during the survival and recovery intervals’”.[8] Further supporting their radiation to other parts of Pangea that lead to the high diversification during the Early Triassic.[11] Also resulting in the spreading from South Africa to South America (Brazil) where more fossils of Stereospondyls were found.[11] Even a mandible from the Lower Anisian Mukheiris Formation in Jordan was discovered, and shared many similarities with the genus, including a similarly sized Meckelian fenestra on the inner surface of the lower jaw, teeth with sharp edges, and large fangs in the upper jaw.[12]

References

- Damiani, Ross (2004). "Cranial anatomy and relationships of Microposaurus casei, a temnospondyl from the Middle Triassic of South Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (3): 533–41. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0533:caarom]2.0.co;2.

- Warren, Anne (2012). "The South African stereospondyl Microposaurus from the Middle Triassic of the Sydney Basin, Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (3): 538–44. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.658934.

- Butler, Richard (3 May 2013). "Wonderboom Bridge, Burgersdorp, Farm Cragievar (Triassic of South Africa)". PaleobioDB. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- Haughton, Sydney (1925). "Investigations in South African fossil reptiles and amphibia". Annals of the South African Museum. 22: 227–61 – via BioStor.

- Butler, Richard (28 November 2012). "7km SE of Picton (Triassic of Australia)". PaleoBioDB. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Ward, Peter; Montgomery, David; Smith, Roger (2000). "Altered river morphology in South Africa related to the Permian-Triassic extinction". Science. 289 (5485): 1740–743. doi:10.1126/science.289.5485.1740. PMID 10976065.

- Sébastien, Steyer (2002). "The first articulated trematosaur 'amphibian' from the Lower Triassic of Madagascar: Implications for the Phylogeny of the Group". Palaeontology. 45 (4): 771–93.

- Scheyer, Torsten; Romano, Carlo; Jenks, Jim; Bucher, Hugo (2014). "Early Triassic marine biotic recovery: The predators' perspective". PLoS ONE. 9: e88987. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088987. PMC 3960099. PMID 24647136.

- Hammer, W.R. (1987). "Paleoecology and phylogeny of the Trematosauridae". Gondwana Six: Stratigraphy, Sedimentology, and Paleontology Geophysical Monograph Series: 73–83.

- Haig, David; Martin, Sarah; Mory, Arthur; Mcloughlin, Stephen; Backhouse, John; Berrell, Rodney; Kear, Benjamin; Hall, Russell; Foster, Clinton (2015). "Early Triassic (early Olenekian) life in the interior of East Gondwana: mixed marine–terrestrial biota from the Kockatea Shale, Western Australia". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 417: 511–33. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.10.015.

- Dias-Da-Silva, Sérgio; Dias, Eliseu; Schultz, Cesar (2009). "First record of stereospondyls (Tetrapoda, Temnospondyli) in the Upper Triassic of Southern Brazil". Gondwana Research. 15 (1): 131–36. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2008.07.002.

- Schoch, R.R. (2011). "A trematosauroid temnospondyl from the Middle Triassic of Jordan". Fossil Record. 14 (2): 119–27. doi:10.1002/mmng.201100002.