Chopsticks

Chopsticks are shaped pairs of equal-length sticks that have been used as kitchen and eating utensils in most of East Asia for over three millennia. They are held in the dominant hand, secured by fingers, and wielded as extensions of the hand, to pick up small pieces of food.

• Taiwanese melamine chopsticks

• Chinese porcelain chopsticks

• Tibetan bamboo chopsticks

• Vietnamese palmwood chopsticks

• Korean stainless steel flat chopsticks,

and a matching spoon in a sujeo

• Japanese couple's set (two pairs)

• Japanese child's chopsticks

• disposable bamboo chopsticks

(in paper wrapper)

| Chopsticks | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) The original Chinese character for "chopsticks"[upper-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 筷子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 箸 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | đũa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Nôm | 箸 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 젓가락 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 箸 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 箸 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | はし | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

First used by the Chinese, chopsticks later spread to other East Asian cultural sphere countries including Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Taiwan. As ethnic Chinese emigrated, the use of chopsticks as eating utensils for certain ethnic food took hold in South and Southeast Asian countries such as Cambodia, Laos, Nepal, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, and Thailand. In Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Nepal, chopsticks are generally used only to consume noodles. Similarly, chopsticks have become more accepted in connection with Asian food in Hawaii, the West Coast of North America, and cities with Overseas Asian communities all around the globe.

Chopsticks are smoothed, and frequently tapered. They are traditionally made of wood, bamboo, metal, ivory, and ceramics. But in modern days, they are increasing available in non-traditional materials such as plastic, stainless steel, and even titanium.

Origin and history

The Han dynasty historian Sima Qian wrote that chopsticks were known before the Shang dynasty (1766–1122 BCE). But there is no textual or archeological evidence to support this statement.[1] The earliest evidence uncovered so far consists of six chopsticks, made of bronze, 26 centimetres (10 in) long, and 1.1 to 1.3 centimetres (0.43 to 0.51 in) wide, excavated from the Ruins of Yin near Anyang (Henan). These are dated roughly to 1200 BCE. They were supposed to be have been used for cooking.[2][3][4] The earliest known textual reference to the use of chopsticks comes from the Han Feizi, a philosophical text written by Han Fei (c. 280–233 BCE) in the 3rd century BCE.[5]

As cooking utensils

The first chopsticks were used for cooking, stirring the fire, serving or seizing bits of food, and not as eating utensils. One reason was that before the Han dynasty, millet was predominant in North China, Korea and parts of Japan. While chopsticks were used for cooking, millet porridge was eaten with spoons at that time.[6]:29-35 The use of Chopsticks in the kitchen continues to this day.

Ryoribashi (料理箸 | りょりばし) are Japanese kitchen chopsticks used in Japanese cuisine. They are used in the preparation of Japanese food, and are not designed for eating. These chopsticks allow handling of hot food with one hand, and are used like regular chopsticks. These chopsticks have a length of 30 centimetres (12 in) or more, and may be looped together with a string at the top. They are usually made from bamboo. For deep frying, however, metal chopsticks with bamboo handles are preferred, as tips of regular bamboo chopsticks become discolored and greasy after repeated use in hot oil. The bamboo handles protect against heat.

Similarly, Vietnamese cooks use oversized đũa cả (𥮊奇) or "grand chopsticks" in cooking, and for serving rice from the pot.[7]

As eating utensils

Chopsticks began to be used as eating utensils during the Han dynasty, as rice consumption increased. During this period, spoons continued to be used alongside chopsticks as eating utensils at meals. It was not until the Ming dynasty that chopsticks came into exclusive use for both serving and eating. They then acquired the name kuaizi and the present shape.[8][6]:6-8

Propagation throughout the world

The use of chopsticks as both cooking and eating utensils spread throughout East Asia over time. Scholars such as Isshiki Hachiro and Lynn White have noted how the world was split among three dining customs, or food cultural spheres. There are those eating with fingers, and those with forks and knives. Then there is the "chopsticks cultural sphere", consisting of China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam.[6]:1-3, 67-92

As ethnic Chinese emigrated, the use of chopsticks as eating utensils for certain ethnic food took hold in South and Southeast Asian countries such as Cambodia, Laos, Nepal, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore and Thailand. In Singapore and Malaysia, the ethnic Chinese traditionally consume all food with chopsticks, while ethnic Indians and Malays (especially in Singapore) use chopsticks only to consume noodle dishes. Overall, the use of a spoon or fork is more common in these regions.[9][10] In Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Nepal chopsticks are generally used only to consume noodles.[6]:1–8

Similarly, chopsticks have become more accepted in connection with Asian food in Hawaii, the West Coast of North America,[11][12] and cities with Overseas Asian communities all around the globe.

The earliest European reference to chopsticks comes in the Portuguese Suma Oriental by Tomé Pires, who wrote in 1515 in Malacca: "They [the Chinese] eat with two sticks and the earthenware or china bowl in their left hand close to the mouth, with the two sticks to suck in. This is the Chinese way."[13]

Naming in different countries

In ancient written Chinese, the character for chopsticks was zhu (箸; Middle Chinese reconstruction: d̪jwo-). Although it may have been widely used in ancient spoken Chinese, its use was eventually replaced by the pronunciation for the character kuài (快), meaning "quick". The original character, though still used in writing, is rarely used in modern spoken Chinese. It, however, is preserved in Chinese dialects such as Hokkien and Teochew as the Min Chinese languages are directly descended from Old Chinese rather than Middle Chinese.

The Standard Chinese term for chopsticks is kuàizi (Chinese: 筷子). The first character (筷) is a semantic-phonetic compound created with a phonetic part meaning "quick" (快), and a semantic part meaning "bamboo" (竹), using the radical (⺮).[14][15]

The English word "chopstick" may have derived from Chinese Pidgin English, in which chop chop meant "quickly".[16][17][18] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest published use of the word is in the 1699 book Voyages and Descriptions by William Dampier: "they are called by the English seamen Chopsticks".[19] Another possibility, is that the term is derived from chow (or chow chow) which is also a pidgin word stemming from Southeast Asia meaning "food". Thus chopsticks would simply mean "food sticks".

In Japanese, chopsticks are called hashi (箸). They are also known as otemoto (おてもと), a phrase commonly printed on the wrappers of disposable chopsticks. Te means hand and moto means the area under or around something. The preceding o is used for politeness.

In Okinawan, chopsticks are called mēshi めーし as a vulgar word,[20] umēshi うめーし as a polite word,[21] or 'nmēshi ぅんめーし(御箸,ʔNmeesi).[22] A special type of chopsticks made from the himehagi (a Japanese word referring to Polygala japonica) stem is called sōrō 'nmēshi そーろーぅんめーし (sooroo ʔNmeesi精霊御箸). These are used at altars of offerings in Kyū Bon (old Bon Festival). [23]

In Korean, 저 (箸, jeo) is used in the compound jeotgarak (Hangul: 젓가락), which is composed of jeo ("chopsticks") and garak ("stick"). Jeo cannot be used alone, but can be found in other compounds such as sujeo (Hangul: 수저) ("spoon and chopsticks").

In Taiwanese Hokkien, which is derived from Hokkien, chopsticks are called tī, written as 箸.[24]

In Vietnamese, chopsticks are called đũa, which is written as 𥮊 with 竹 trúc ("bamboo") as the semantic, and 杜 đỗ as the phonetic part. It is an archaic borrowing of the older Chinese term for chopsticks, 箸.

In Cambodian (Khmer), chopsticks are called chang keuh (ចង្កឹះ).

In Filipino, chopsticks are referred to as sipit ng intsik which is a compound of sipit ( "to grip" or "pincers") and intsik ("Chinese").[25]

Styles of chopsticks

Common characteristics

Chopsticks come in a wide variety of styles, with differences in geometry and material. Depending on the country and the region some chopstick styles are more common than others.

- Length: Chopsticks range from 23 centimetres (9.1 in) to 26 centimetres (10 in) long, tapering to one end. Very long, large chopsticks, usually about 30 or 40 centimetres (12 or 16 in), are used for cooking, especially for deep frying foods.

- Cross-section: Chopsticks may have round, square, hexagonal, or other polygonal cross-sections. Usually the edges are rounded off so there are no sharp 90° surface angles in square chopsticks. Korean chopsticks are notable for having flat handles, instead of regular full bodies as in Chinese and Japanese chopsticks.

- Taper: Chopsticks are usually tapered in the end used for picking up food. Chinese chopsticks are more commonly blunt, while Japanese ones tend to be sharp and pointed in style. Korean chopsticks typically have sharp tapers.

- Tips: Some chopsticks have a rough surface for the tip end, to provide better friction for gripping food. The gripping surfaces may be carved as circumferential grooves, or provided as a rough texture.

- Material: A large variety of materials is available, including bamboo, wood, plastic, metal, bone, jade, porcelain, and ivory.

- Bamboo and wood chopsticks are relatively inexpensive, low in temperature conduction, and provide good grip for holding food. They can warp and deteriorate with continued use if they are of the unvarnished or unlacquered variety. Almost all cooking and disposable chopsticks are made of bamboo or wood. Disposable unlacquered chopsticks are used especially in restaurants. These often come as a piece of wood that is partially cut and must be split into two chopsticks by the user (serving as proof that they have not been previously used). In Japanese, these disposable implements are known as waribashi (割り箸)

- Plastic chopsticks are relatively inexpensive, low in temperature conduction, and resistant to wear. Melamine is one of the more commonly used plastics for chopsticks. Plastic chopsticks are not as effective as wood and bamboo for picking up food, because they tend to be slippery. Also, plastic chopsticks cannot be used for cooking, since high temperatures may damage the chopsticks and produce toxic compounds.

- Metal chopsticks are durable and easy to clean, but present a slippery surface. Stainless steel chopsticks are a common metal used to make chopsticks, but titanium chopsticks can be purchased at prices comparable to a good pair of wooden chopsticks. Silver is still common among wealthy families.

- Other materials such as ivory, jade, gold, and silver are typically chosen for luxury. Silver-tipped chopsticks were often used as a precaution by wealthy people, as it was believed that the silver would turn black upon contact with poison.[26]

- Embellishments: Wooden or bamboo chopsticks can be painted or lacquered for decoration and waterproofing. Metal chopsticks are sometimes roughened or scribed to make them less slippery. Higher-priced metal chopstick pairs are sometimes connected by a short chain at the untapered end to prevent their separation.

China

Chinese chopsticks tend to be longer than other styles, at about 27 centimetres (11 in). They are thicker, with squared or rounded cross-sections. They end in either wide, blunt, flat tips or tapered pointed tips. Blunt tips are more common with plastic or melamine varieties, whereas pointed tips are more common in wood and bamboo varieties. Chinese restaurants more commonly offer melamine chopsticks for its durability and ease of sanitation. Within individual household, bamboo chopsticks are more commonly found.

Japan

It is common for Japanese sticks to be of shorter length for women, and children's chopsticks in smaller sizes are common. Many Japanese chopsticks have circumferential grooves at the eating end, which helps prevent food from slipping. Japanese chopsticks are typically sharp and pointed. They are traditionally made of wood or bamboo, and are lacquered.

Lacquered chopsticks are known in Japanese as nuribashi, in several varieties, depending on where they are made and what types of lacquers are used in glossing them.[6]:80–87 Japan is the only place where they are decorated with natural lacquer, making them not just functional but highly attractive. Japanese traditional lacquered chopsticks are produced in the city of Obama in Fukui Prefecture, and come in many colors coated in natural lacquer. They are decorated with mother-of-pearl from abalone, and with eggshell to impart a waterproof coating to the chopsticks, extending their life.[27]

Edo Kibashi chopsticks have been made by Tokyo craftspeople since the beginning of the Taishō Period (1912-1926) roughly 100 years ago. These chopsticks use high-grade wood (ebony, red sandalwood, ironwood, Japanese box-trees, or maple), which craftspeople plane by hand.[28] Edo Kibashi chopsticks may be pentagonal, hexagonal or octagonal in cross-section. The tips of these chopsticks are rounded to prevent to damage the dish or the bowl.[29]

In Japan, chopsticks for cooking are known as ryoribashi (料理箸 | りょりばし),[30] and as saibashi (菜箸 | さいばし) when used to transfer cooked food to the dishes it will be served in.[31]

Korea

Unique among East Asian cultures, chopsticks used by Koreans are often made of metal. Depending on the historical era, the metallic composition of Korean chopsticks varied. In the past, such as during the Goryeo era, chopsticks were made of bronze. During the Joseon era, chopsticks used by royalty were made of silver, as its oxidizing properties could often be used to detect whether or not food intended for royals had been tampered with. In the present day, the majority of Korean metal chopsticks are made of stainless steel. High-end sets, such as those intended as gifts, are often made of sterling silver. Chopsticks made of varying woods (typically bamboo) are also common in Korea. Many Korean chopsticks are ornately decorated at the grip.

In North and South Korea, chopsticks of medium-length with a small, flat rectangular shape are paired with a spoon, made of the same material. The set is called sujeo, a portmanteau of the Korean words for spoon and chopsticks. This is a feature unique to Korea. Most chopstick-using countries have either eliminated the use of spoons, or have limited their use as eating utensils. It is traditional to rest sujeo on spoon and chopstick rest, so chopsticks and the spoon do not touch the table surface.

In the past, materials for sujeo varied with social class: Sujeo used in the court were made with gold, silver, or cloisonné, while commoners used brass or wooden sujeo. Today, sujeo is usually made with stainless steel, although bangjja is also popular in more traditional settings.

Vietnam

Vietnamese chopsticks are long sticks that taper to a blunt point. They are traditionally made of bamboo or lacquered wood. A đũa cả (from chữ nôm: 𥮊奇) are large, flat chopsticks used to serve rice from a pot. Plastic chopsticks are also used due to their durability. However, bamboo or wooden chopsticks are often more popular, especially in the village countryside (quê).

Using chopsticks

Chopstick grips

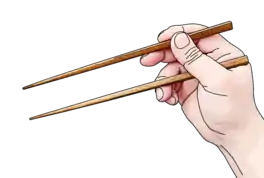

Lifelong users and adult learners alike, around the world, hold chopsticks in more than one way. But there is a general consensus on a standard grip being the most efficient way to grip and wield chopsticks.[32]

Regardless of whether users wield the standard grip, or one of many alternative grips, their goals are the same. They hold the two sticks in the dominant hand, secured by various fingers and parts of the hand, such that the sticks become an extension of the hand. Tsung-Dao Lee, a Nobel Prize Laureate in Physics, summarized it thus: "Although simple, the two sticks perfectly use the physics of leverage. Chopsticks are an extension of human fingers. Whatever fingers can do, chopsticks can do, too."[6]:14

Alternative grips differ in their effectiveness in picking up food. They differ in the amount of pinching (compression) power they can generate. Some grips can generate substantial, outward extension force, while others are unable to do so.

Standard grip

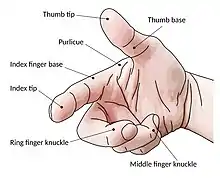

The standard grip calls for the top chopstick to be held by the tip of the thumb, the tip of the index finger, and the middle finger knuckle. These three fingers surround the top stick from three sides, and firmly secure the stick as if they were holding a pen. The three fingers, using this tripod-like hold, can wiggle and twirl the top stick, as if it were an extension of them. The rear end of the top stick rests on the base of the index finger.

The bottom chopstick, on the other hand, generally remains immobile. It is secured by the base of the thumb, which presses the stick against the knuckle of the ring finger, and against the purlicue. The thumb therefore does double duty. It holds the bottom stick immobile, and at the same time, it also moves the top stick. The thumb must be flattened, in order to perform this double duty.[33]

Learning to use chopsticks

In chopstick-using cultures, learning to use chopsticks is part of a child's development process. The right way to use chopsticks is usually taught within the family.[upper-alpha 2] But many young children find their own ways of wielding chopsticks in the process.[32] There exists a variety of learning aids that parents purchase to help their children learn to use chopsticks properly.

Adult learners, on the other hand, may acquire the skill through personal help from friends, or from instructions printed on wrapper sleeves of some disposable chopsticks. Various video hosting platforms also provide plethora of how-to videos on learning to use chopsticks. All the same, adult learners too., often find their own alternative grips to using chopsticks.

In general, learning aids attempt to steer learners towards the established standard grip. These aids attempt to illustrate or enforce the right standard grip mechanical leverage.

Full range of chopstick motion

The learning process usually starts with a proper initial placement of fingers, per standard grip. It is crucial for learners to understand how to hold both sticks firmly in the hand, as extensions of fingers.

The next step involves learning the right motion of fingers, in order to move the top stick from the closed posture where tips of chopsticks touch, to the open posture where tips are extended wide apart for embracing food items. The open posture and the closed posture define the two ends of maximum standard grip motion. In most eating situations, tips of chopsticks need not be extended thus wide apart.

Both finger placement and standard grip motion rely on the thumb being flattened. With this flat thumb pose, the base of the thumb can exert enough force to pin the bottom stick against the knuckle of the ring finger, and against the purlicue. At the same time, the tip of the thumb pushes back against the index finger and the knuckle of the middle finger, as all three wield the top stick in concert.[34]

The shape of the flat thumb is such that the bottom stick is prevented from shaking lose, and from inching closer to the top stick, during repeated standard grip motion. Keeping the two chopsticks separated far enough, at the place they intersect with the thumb, is important for the standard grip. At the open posture, it allows tips to extend wide apart, without rear ends of chopsticks colliding. At the closed posture, it enables better control over tips of chopsticks.[upper-alpha 2]

Learning aids

The most popular chopstick learning aid is arguably the wrapper-sleeve-and-rubber-band model, found used in ethnic restaurants around the world. These are mostly operated like tweezers, or tongs. While they are useful for picking up food, they do not help learners acquire the standard grip. Many similar chopstick inventions can be found on the market, such as Kwik Stix. Some inventions combine other utensils with chopsticks. These include The Chork, the Fork and Knife Chopsticks, etc.

Some learning aids actually help learners with the initial placement of fingers, per standard grip. This can be done by making "index finger", "thumb tip", or equivalent labels at the right places on chopsticks. Often these chopsticks will have finger-shaped grooves carved out of sticks, to further help learners find the right placement. Other finger placement chopsticks instead carve circumferential grooves into sticks, in place of finger-shaped ones.

Some learning aids allow users to wield two sticks as extensions of their fingers, without the exact finger dynamics required by the standard grip. Some models provide hoops through which fingers can move the top chopstick as an exoskeleton of these fingers. Other models use finger-shaped tabs instead to achieve the same, for both top and bottom sticks. Yet other models combine finger placement features with the above. Usually these models connect the two chopsticks with a bridge and a hinge, holding the two sticks in the right configuration on behalf of users.

Chopstick customs, manners and etiquette

Chopsticks are used in many parts of the world. While principles of etiquette are similar, finer points can differ from region to region. Chopstick manners were gradually shaped to work with a culture's particular dietary varieties and habit. Etiquette developed for primarily individual servings eaten on the floor (or tatami in the case of Japan) could be different from communal meals eaten around a round table while seated on chairs. The need for serving or communal chopsticks similarly differ. In some cultures it is customary to lift a bowl to the mouth, when the only eating utensil used is chopsticks. In other cultures, lifting a bowl closer to the mouth is frowned upon as equivalent to begging, as the local custom is to use chopsticks for chunky food, and a spoon for liquid food.[6]:102-119

In chopstick-using countries, holding chopsticks incorrectly reflects negatively on a child's parents and home environment. There are frequent news articles on the alarming decline of children's abilities to use chopsticks correctly. Similarly, stabbing food due to one's inability to wield chopsticks with dexterity is also frowned upon. [35]:73-75 [36] [37]

In general, chopsticks should not be left vertically stuck into a bowl of rice because it resembles the ritual of incense-burning that symbolizes "feeding" the dead. [38] [39] [40]

China

- When eating rice from a bowl, it is normal to hold the rice bowl up to one's mouth and use chopsticks to push or shovel the rice directly into the mouth.

- It is traditionally acceptable to transfer food using one's own chopsticks to closely-related people. Family members transfer a choice piece of food from a dish to an elderly before dinner starts, as a sign of respect. In modern times, the use of serving or communal chopsticks for this transfer has gained momentum, for better sanitary practices. [41]

- Chopsticks, when not in use, are placed either to the right or below one's plate in a Chinese table setting. [35]:35

- It is poor etiquette to tap chopsticks on the edge of one's bowl; beggars make this sort of noise to attract attention. [42] [43]

- One should not "dig" or "search" through food for something in particular. This is sometimes known as "digging one's grave" or "grave-digging" and is extremely poor form.[6]:116

Japan

- The pointed ends of the chopsticks should be placed on a chopstick rest when the chopsticks are not being used. However, when a chopstick rest is not available as is often the case in restaurants using waribashi (disposable chopsticks), chopstick wrappers may be folded into a rest.[39]

- Reversing chopsticks to use the opposite clean end can be used to move food from a communal plate, and is acceptable if there are no communal chopsticks.[40] In general, reversing chopsticks (逆さ箸 sakasabashi) is frowned upon, however, because of the association to the celebratory chopsticks (祝い箸 iwai-bashi), where both ends of chopsticks are tapered, but only one end is for man to use, while the other is for use by god.[44]

- Chopsticks should not be crossed on a table, as this symbolizes death.[45]:154

- Chopsticks should be placed in the right-left direction, and the tips should be on the left.[45]:61

- In formal use, disposable chopsticks (waribashi) should be replaced into the wrapper at the end of a meal.[39]

Korea

- In Korea, chopsticks are paired with a spoon, forming a sujeo set. Sujeo are placed on the right side and parallel to bap (rice) and guk (soup). Chopsticks are laid on the right side of the paired spoon. One must never put the chopsticks to the left of the spoon. Chopsticks are only laid to the left during the food preparation for the funeral or the memorial service for the deceased family members, known as jesa. [46]

- Spoon is used for bap (rice) and soupy dishes, while most other banchan (side dishes) are eaten with chopsticks.[47]

- It is considered uncultured and rude to pick up a plate or a bowl to bring it closer to one's mouth, and eat its content with chopsticks. If the food lifted "drips", a spoon is used under the lifted food to catch the dripping juices. Otherwise however, holding both a spoon and chopsticks in one hand simultaneously or in both hands is usually frowned upon.[48]

Vietnam

Vietnam is one of the countries in the original "chopsticks cultural sphere". Its customs are heavily influenced by its Chinese counterparts, including using chopsticks exclusively as eating utensils. Consequently Vietnamese chopstick etiquette are very similar to Chinese ones[6]:69, 73 For instance, it is deemed proper to hold the bowl close to the mouth, just like is the case in China. Holding chopsticks vertically up like incense sticks is taboo. Tapping bowls with chopsticks is frowned upon. [49]

Cambodia

In Cambodia, chopsticks are not the primary eating utensil. A fork and a spoon are the primary eating utensils. Forks are only used to help guide food onto the spoon. Forks are not used to shovel food into the mouth. For noodle dishes such as Kuy teav, Num Banh Chok, chopsticks are used instead, to pick up food for eating. In this case, the spoon is used for picking up the broth. [50]

Thailand

- Historically, Thai people used bare hands to eat and occasionally used a spoon and fork for curries or soup, an impact from the west. But many Thai noodle dishes, served in a bowl are eaten with chopsticks. [51] [52]

- Unlike in China and in Vietnam, chopsticks are not be used with a bowl of rice.[53]

- It is considered impolite to make a sound with chopsticks.[53]

- It is poor etiquette to rest or hold chopsticks pointing towards others, as pointing is considered disrespectful.[53]

Global impacts

Environmental impacts

The most widespread use of disposable chopsticks is in Japan, where around a total of 24 billion pairs are used each year,[54][55][56] which is equivalent to almost 200 pairs per person yearly.[57] In China, an estimated 45 billion pairs of disposable chopsticks are produced yearly.[57] This adds up to 1.66 million cubic metres (59×106 cu ft) of timber[58] or 25 million fully grown trees every year.[57]

In April 2006, China imposed a 5% tax on disposable chopsticks to reduce waste of natural resources by overconsumption.[59][60] This measure had the most effect in Japan as many of its disposable chopsticks are imported from China,[57] which account for over 90% of the Japanese market.[56][61]

American manufacturers have begun exporting American-made chopsticks to China, using sweet gum and poplar wood as these materials do not need to be artificially lightened with chemicals or bleach, and have been seen as appealing to Chinese and other East Asian consumers.[62]

The American-born Taiwanese singer Wang Leehom has publicly advocated the use of reusable chopsticks made from sustainable materials.[63][64] In Japan, reusable chopsticks are known as maihashi or maibashi (マイ箸, meaning "my chopsticks").[65][66]

See also

Notes

- Still widely used across East Asia, but in China has become archaic in most Chinese dialects except Min Chinese.

- There is a lack of written literature on the variety of chopstick grips, naming of these, classifications of these, factors used to determine grip differences, etc. There is also a lack of literature on the presumed standard grip, its physics, and its mechanical leverage. Detailed written literature on how to learn the standard grip has yet to be discovered. For the time being, summaries written in this article on the use of chopsticks can be substantiated by direct observations of a person using chopsticks, and by watching online videos.[6]:166-167

References

- H.T. Huang (Huang Xingzong). Fermentations and Food Science. Part 5 of Biology and Biological Technology, Volume 6 of Joseph Needham, ed., Science and Civilisation in China, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000 ISBN 0-521-65270-7), p. 104

- 卢茂村 (Lu, Maocun). "筷子古今谈 (An Introduction to Chopsticks)", 农业考古 (Agricultural Archaeology), 2004, No. 1:209–216. ISSN 1006-2335.

- "Le due leggende sulle bacchette cinesi". Italian.cri.cn. 2008-06-19. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- (in Chinese) 嚴志斌 洪梅编著 『殷墟青銅器︰青銅時代的中國文明』 上海大学出版社, 2008-08, p. 48 "第二章 殷墟青銅器的類別與器型 殷墟青銅食器 十、銅箸 这三双箸长26、粗细在1.1-1.3厘米之间,出土于西北岗1005号大墓。陈梦家认为这种箸原案有长形木柄,应该是烹调用具。" ISBN 7811180979 OCLC 309392963.

- Needham, Joseph. (2000). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 5, Fermentations and Food Science. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. footnote 161.

- Wang, Q. Edward (2015). Chopsticks: A cultural and culinary history. England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107023963 – via Google Books.

- "Đôi đũa". Batkhuat.net. 2011-06-19. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- Endymion Wilkinson, Chinese History: A Manual (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Rev. and enl., 2000), 647 citing Yun Liu, Renxiang Wang, Qin Mu, 木芹. 刘云. 王仁湘 刘云 Zhongguo Zhu Wen Hua Da Guan 中国箸文化大观 (Beijing: Kexue chubanshe, 1996).

- "Etiquette in Singapore | Frommer's". www.frommers.com.

- Suryadinata, Leo (1 January 1997). Ethnic Chinese as Southeast Asians. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789813055506 – via Google Books.

- "Forget the chopsticks, give us forks | YouGov". today.yougov.com.

- "Learning the Art of Chopsticks - Hawaii Aloha Travel". 7 June 2012.

- The Suma oriental of Tome Pires p.116

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2000). Chinese history: A manual. Cambridge: Harvard University. p. 647. ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4.

- Norman, Jerry (1988) Chinese, Cambridge University Press, p76.

- Merriam-Webster Online. "Definition of chopstick".

- Norman, Jerry (1988) Chinese, Cambridge University Press, p267.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 269.

- Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition 1989

- "語彙詳細 — 首里・那覇方言". ryukyu-lang.lib.u-ryukyu.ac.jp. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- "語彙詳細 — 首里・那覇方言". ryukyu-lang.lib.u-ryukyu.ac.jp. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- http://ryukyu-lang.lib.u-ryukyu.ac.jp/srnh/details.php?ID=SN50386

- http://ryukyu-lang.lib.u-ryukyu.ac.jp/srnh/details.php?ID=SN50947

- "【箸】 tī" (PDF). Ministry of Education, R.O.C. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- "Sipit Meaning | Tagalog Dictionary". Tagalog English Dictionary. Retrieved 2019-01-13.

- Access Asia: Primary Speaking and Learning Units. Carlton, Vic.: Curriculum Corporation. 1996. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-86366-345-8.

- Megumi, I. (Producer), & Masahiko, H. (Director). (2009). Begin Japanology-Chopsticks [Video file].

- Edo Kibashi Chopsticks. (2019). Retrieved from https://japan-brand.jnto.go.jp/crafts/woodcraft/2784/

- NHK (Producer). (2006). Binotsubo-Chopsticks [Video file].

- Shimbo, Hiroko (2000). The Japanese Kitchen. Boston, MA: Harvard Common Press. p. 15. ISBN 1-55832-177-2.

- "さいばし". Shogakukan and NTT Resonant Inc. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- 山内知子; 小出あつみ; 山本淳子; 大羽和子 (2010). "食育の観点からみた箸の持ち方と食事マナー". 日本調理科学会誌. 情報知識学会. 43 (4): 260–264. doi:10.11402/cookeryscience.43.260.

- Reiber, Beth; Spencer, Janie (2010). Frommer's Japan. John Wiley & Sons. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-470-54129-6.

The proper way to use a pair is to place the first chopstick between the base of the thumb and the top of the ring finger (this chopstick remains stationary) and the second one between the top of the thumb and the middle and index fingers.

- Ashcraft, Brian (2018-01-31). "How To Use Chopsticks". Kotaku. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- Giblin, James Cross (1987). From hand to mouth: How we invented knives, forks, spoons, and chopsticks, & the manners to go with them. New York: Crowell. ISBN 978-0-690-04660-1.

- Watanabe, Teresa (1992-06-23). "Culture : Japanese Losing Their Grip on Ancient Skill of Wielding Chopsticks : Most young children don't know the proper technique. Some even commit the ultimate crime: spearing their dinner". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2021-01-03. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- "Chinese Chopsticks". chinaculture.org. p. 4. Archived from the original on 2012-04-28. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- "Manners in the world". 오마이뉴스. 2017-09-05. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- Vardaman, James; Sasaki Vardaman, Michiko (2011). Japanese Etiquette Today: A Guide to Business & Social Customs. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 68–69. ISBN 9781462902392.

- De Mente, Boye Lafayette (2011). Etiquette Guide to Japan: Know the rules that make the difference!. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9781462902460.

- Ying, Zhu (2020-04-25). "Chopsticks: Eating habits under scrutiny". Shine. Archived from the original on 2020-11-24. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- "Difference". Chinatoday.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2012-07-21. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- "Pandaphone". Pandaphone. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- "祝い箸の基礎知識|さまざまな呼び名の由来と正しい使い方". 正直屋. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- Tokyo YWCA World Fellowship Committee (1955). Japanese Etiquette: An Introduction. Tuttle Publishing. p. 154. ISBN 9780804802901.

- "Where should I put the spoon on the table? Correct spot location" (in Korean). Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- Lee, MinJung (2009). Step by Step Cooking Korean: Delightful Ideas for Everyday Meals (New ed.). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. p. 9. ISBN 978-981-261-799-6.

- Park, Hannah (2014). Korean Culture for Curious New Comers. Translated by Chun, Chong-Hoon. Pagijong Press. p. 117. ISBN 9788962927252.

- "The Ultimate Guide to Customs and Etiquette in Vietnam". Vietnam Visa. Archived from the original on 2020-01-03. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- Gilbert, Abigail. "Cambodian Table Manners". travelfish.org.

- "The Scoop on Chopsticks in Thai Food". Brooklynbrainery.com. 2012-01-30. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- "Bangkok". CNN.

- "วัฒนธรรมตะเกียบ ... สนเทศน่ารู้". www.lib.ru.ac.th.

- Hayes, Dayle; Laudan, Rachel (2009). Food and Nutrition. New York: Marshall Cavendish Reference. p. 1043. ISBN 978-0-7614-7827-0.

- Rowthorn, Chris (2007). Japan (10th ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-74104-667-0.

- "Rising Chinese chopstick prices help Japan firm". Asia Times Online. Asia Times. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Japan fears shortage of disposable chopsticks: China slaps 5 percent tax on wooden utensils over deforestation concerns". NBC News. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- "Annual output of 4 billion pairs of biodegradable plant fiber chopsticks project of Jilin Agricultural Science Hi-tech Industry Co., Ltd". People's Government of Jilin Province. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "China imposes chopsticks tax". ABC News. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "As China goes ecological, Japan fears shortage of disposable chopsticks". USA TODAY. 2006-05-12. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- McCurry, Justin (2006-05-14). "Japan faces chopsticks crisis". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- Philip Graitcer (2011-07-17). "Chopsticks Carry 'Made in America' Label". Voanews.com. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- "Wang Leehom, "Change My Ways"". english.cri.cn. 2007-08-22. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- "Career". Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- "Chopstick Economics and the "My Hashi" Boom | Japan". Stippy. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 April 2009. Retrieved 21 April 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Hong Kong Department of Health survey". .news.gov.hk. 2006-12-26. Archived from the original on 2009-05-05. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chopsticks. |

| Look up chopsticks in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)