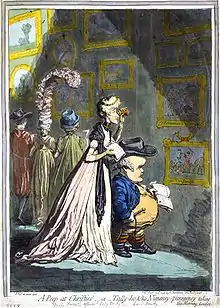

Christie's

Christie's is a British auction house founded in 1766 by James Christie. Its main premises are on King Street, St James's in London and in Rockefeller Center in New York City.[1] It is owned by Groupe Artémis, the holding company of François-Henri Pinault.[2] Sales in 2015 totalled £4.8 billion (US$7.4 billion).[3] In 2017, the Salvator Mundi was sold for $400 million at Christie's in New York, at the time the highest price ever paid for a single painting at an auction.[4]

Christie's in King Street, St James's | |

| Type | Subsidiary |

|---|---|

| Industry | Art, auctions |

| Founded | 1766 |

| Founder | James Christie |

| Headquarters | , United Kingdom |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | François-Henri Pinault Guillaume Cerutti (CEO) |

| Parent | Groupe Artémis |

| Website | christies |

_001.jpg.webp)

History

Founding

The official company literature states that founder James Christie (1730–1803) conducted the first sale in London, England, on 5 December 1766,[5] and the earliest auction catalogue the company retains is from December 1766. However, other sources note that James Christie rented auction rooms from 1762, and newspaper advertisements for Christie's sales dating from 1759 have also been traced.[6] After his death, Christie's son, James Christie the Younger (1773–1831) took over the business.[7]

1979–1990s

Christie's was a public company, listed on the London Stock Exchange, from 1973 to 1999. In 1974, Jo Floyd was appointed chairman of Christie's. He served as chairman of Christie's International plc from 1976 to 1988, until handing over to Lord Carrington, and later was a non-executive director until 1992.[8] Christie's International Inc. held its first sale in the United States in 1977. Christie's growth was slow but steady since 1989, when it had 42% of the auction market.[9]

In 1990, the company reversed a long-standing policy and guaranteed a minimum price for a collection of artworks in its May auctions.[10] In 1996, sales exceeded those of Sotheby's for the first time since 1954.[11] However, profits did not grow at the same pace;[12] from 1993 through 1997, Christie's annual pretax profits were about $60 million, whereas Sotheby's annual pretax profits were about $265 million for those years.[13]

In 1993, Christie's paid $12.7 million for the London gallery Spink & Son, which specialised in Oriental art and British paintings; the gallery was run as a separate entity. The company bought Leger Gallery for $3.3 million in 1996, and merged it with Spink to become Spink-Leger.[14] Spink-Leger closed in 2002. To make itself competitive with Sotheby's in the property market, Christie's bought Great Estates in 1995, then the largest network of independent estate agents in North America, changing its name to Christie's Great Estates Inc.[9]

1998 takeover

In December 1997, under the chairmanship of Lord Hindlip, Christie's put itself on the auction block, but after two months of negotiations with the consortium-led investment firm SBC Warburg Dillon Read it did not attract a bid high enough to accept.[13] In May 1998, François Pinault's holding company, Groupe Artémis S.A., first bought 29.1 percent of the company for $243.2 million, and subsequently purchased the rest of it in a deal that valued the entire company at $1.2 billion.[12] The company has since not been reporting profits, though it gives sale totals twice a year. Its policy, in line with UK accounting standards, is to convert non-UK results using an average exchange rate weighted daily by sales throughout the year.[15]

Price-fixing scandal in 2000

In 2000, allegations surfaced of a price-fixing arrangement between Christie's and Sotheby's. Executives from Christie's subsequently alerted the Department of Justice of their suspicions of commission-fixing collusion.

Christie's gained immunity from prosecution in the United States as a longtime employee of Christie's confessed and cooperated with the US Federal Bureau of Investigation. Numerous members of Sotheby's senior management were fired soon thereafter, and A. Alfred Taubman, the largest shareholder of Sotheby's at the time, took most of the blame; he and Dede Brooks (the CEO) were given jail sentences, and Christie's, Sotheby's and their owners also paid a civil lawsuit settlement of $512 million.[16][17][18]

2000s

In 2002, Christie's France held its first auction in Paris.[19]

Like Sotheby's, Christie's became increasingly involved in high-profile private transactions. In 2006, Christie's offered a reported $21 million guarantee to the Donald Judd Foundation and displayed the artist's works for five weeks in an exhibition that later won an AICA award for "Best Installation in an Alternative Space".[20] In 2007 it brokered a $68 million deal that transferred Thomas Eakins's The Gross Clinic (1875) from the Jefferson Medical College at the Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia to joint ownership by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.[21] In the same year, the Haunch of Venison gallery[22] became a subsidiary of the company.[23]

On 28 December 2008, The Sunday Times reported that Pinault's debts left him "considering" the sale of Christie's and that a number of "private equity groups" were thought to be interested in its acquisition.[24] In January 2009, the company employed 2,100 people worldwide, though an unspecified number of staff and consultants were soon to be cut due to a worldwide downturn in the art market;[25] later news reports said that 300 jobs would be cut.[26] With sales for premier Impressionist, Modern, and contemporary artworks tallying only US$248.8 million in comparison to US$739 million just a year before, a second round of job cuts began after May 2009.[27] Guy Bennett resigned just before to the beginning of the summer 2009 sales season.[28] Although the economic downturn has encouraged some collectors to sell art, others are unwilling to sell in a market which may yield only bargain prices.[26]

2010 onwards

On 1 January 2017, Guillaume Cerutti was appointed chief executive officer.[29] Patricia Barbizet was appointed chief executive officer of Christie's in 2014, the first female CEO of the company.[30] She replaced Steven Murphy, who had been hired in 2010 to develop their online presence and launch in new markets, such as China.[31] In 2012, Impressionist works, which dominated the market during the 1980s boom, were replaced by contemporary art as Christie's top category. Asian art was the third most-lucrative area.[15]

With income from classic auctioneering falling, treaty sales made £413.4 million ($665 million) in the first half of 2012, an increase of 53% on the same period last year; they now represent more than 18% of turnover.[32] The company has promoted curated events, centred on a theme rather than an art classification or time period.[33]

As part of a companywide review in 2017, Christie's announced the layoffs of 250 employees, or 12 percent of the total work force, based mainly in Britain and Europe.[34]

Commissions

From 2008 until 2013, Christie's charged 25 percent for the first $50,000; 20 percent on the amount between $50,001 and $1 million, and 12 percent on the rest. From 2013, it charged 25 percent for the first $75,000; 20 percent on the next $75,001 to $1.5 million and 12 percent on the rest.[35]

Locations

Christie's main London saleroom is on King Street in St. James's, where it has been based since 1823. It had a second London saleroom in South Kensington which opened in 1975 and primarily handled the middle market. Christie's permanently closed the South Kensington saleroom in July 2017 as part of their restructuring plans announced March 2017. The closure was due in part to a considerable decrease in sales between 2015 and 2016 in addition to the company expanding its online sales presence.[36][37]

In 1977, the company opened its first international branch on Park Avenue in New York City in the Delmonico’s Hotel grand ballroom on the second floor;[38][39] in 1997 it took a 30-year lease on a 28,000 m2 (300,000 sq ft) space in Rockefeller Center for $40 million.[40]

Until 2001, Christie's East, a division that sold lower-priced art and objects, was located at 219 East 67th Street. In 1996, Christie's bought a townhouse on East 59th Street in Manhattan as a separate gallery where experts could show clients art in complete privacy to conduct private treaty sales.[9] Christie's opened a Beverly Hills salesroom in 1997.[41]

In January 2009,[25] Christie's had 85 offices in 43 countries, including New York City, Los Angeles, Paris, Geneva, Houston, Amsterdam, Moscow, Vienna, Buenos Aires, Berlin, Rome, South Korea, Milan, Madrid, Japan, China, Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, Bangkok, Tel Aviv, Dubai, and Mexico City.

In early 2017, Christie's announced plans to close its secondary South Kensington salesroom at the end of the year and scale back its operation in Amsterdam.[34] In April 2017, Christie's is to open a 4,500 square feet two-story flagship space in Beverly Hills, California.[42]

Notable auctions

_(Italian%252C_Florentine)_-_Portrait_of_a_Halberdier_(Francesco_Guardi%253F)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

- In 1848 the sale of the contents of Stowe House after the bankruptcy of the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos was one of the first and most publicised British country house contents auctions. The sale raised £75,400 and included the Chandos portrait of William Shakespeare.[43]

- The 1882 sale of the Hamilton Palace collection raised £332,000.[44]

- In 1987, during the Royal Albert Hall auction, Christie's famously auctioned off a Bugatti Royale automobile for a world record price of £5.5 million.

- In May 1989, Pontormo's Portrait of a Halberdier was sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum for $35.2 million, more than tripling the previous auction record for an Old Master painting.[45]

- On 11 November 1994, the Codex Leicester was sold to Bill Gates for US$30,802,500.[46]

- In 1998, Christie's in New York sold the famous Archimedes Palimpsest after the conclusion of a lawsuit in which its ownership was disputed.

- In November 1999, a single strand necklace of 41 natural and graduated pearls, which belonged to Barbara Hutton, was auctioned by Christie's Geneva for $1,476,000.

- In June 2001, Elton John sold 20 of his cars at Christie's, saying he didn't get the chance to drive them because he was out of the country so often. The sale, which included a 1993 Jaguar XJ220, the most expensive at £234,750, and several Ferraris, Rolls-Royces, and Bentleys, raised nearly £2 million.

- In 2006, a single Imperial Qing Dynasty porcelain bowl, another item which belonged to Barbara Hutton, was auctioned by Christie's Hong Kong for a price of $22,240,000.

- On 16 May 2006, Christie's auctioned a Stradivarius called The Hammer for a record US$3,544,000. It was, at that time, the most paid at public auction for any musical instrument.[47]

- In November 2006, four celebrated paintings by Gustav Klimt were sold for a total of $192 million, after being restituted by Austria to Jewish heirs after a lengthy legal battle.[48]

- In December 2006, a copy of the black dress worn by Audrey Hepburn in the film Breakfast at Tiffany's was sold for £467,200 at Christie's South Kensington.

- In 2006, controversy arose after Christie's auctioned off artefacts known to be looted from Bulgaria.[49][50]

- In November 2007, an album of eight leaves, ink on paper, by China's Ming Dynasty court painter Dong Qichang was sold at the Christie's Hong Kong Chinese Paintings Auction for US$6,235,500, a world auction record for the artist.[51]

- In 2008, the Ink and wash painting of Gundam drawn by Hisashi in 2005 was sold in the Christie's auction held in Hong Kong with a price of US$600,000.[52][53][54][55][56]

- On 24 May 2008, Le Bassin Aux Nymphéas by Claude Monet was sold for a price of $80.4 million, the highest price ever for a Monet.

- Over a three-day sale in Paris in February 2009, Christie's auctioned the monumental private collection of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé for a record-breaking 370 million euros (US$490 million).[57] It was the most expensive private collection ever sold at auction,[58] breaking auction records for Brâncuși, Matisse, and Mondrian.[57] The "Dragons" armchair by Irish furniture designer Eileen Gray sold for 21.9 million euros (US$28 million), setting an auction record for a piece of 20th century decorative art.[59]

- In 2009, controversy arose again after the auction of two imperial bronze zodiac sculptures (for US$36 million) collected by Yves Saint Laurent, stemming from the fact that these items were looted in 1860 from the Old Summer Palace of Beijing by French and British forces at the close of the Second Opium War.[60]

- Christie's Hong Kong, November 2009 sale of Fine Modern Chinese Paintings, sold a work by Fu Baoshi titled Landscape inspired by Dufu's Poetic Sentiments, for HK$60,020,000 (US$7,780,105) – a world record for the artist.

- Christie's auctioned Pablo Picasso's Nude, Green Leaves and Bust on 4 May 2010. The piece sold for US$106.5 million, making the sale among the most expensive paintings ever sold.

- On 14 June 2010 Amedeo Modigliani's Tête, a limestone sculpture of a woman's head, became the second most expensive sculpture ever sold and the most expensive work of art sold in France.

- On 18 April 2012, the silver cup given to the marathon winner, Greek athlete Spyridon Louis, at the first modern Olympic Games staged in Athens in 1896 sold for GB£541,250 (US$860,000), breaking the auction record for Olympic memorabilia.[61]

- On 22 June 2012, George Washington's personal annotated copy of the Acts Passed at a Congress of the United States of America from 1789, which includes The Constitution of the United States and a draft of the Bill of Rights, was sold at Christie's for a record $9,826,500, with fees the final cost, to The Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. This was the record for a document sold at auction.[62]

- On 12 November 2013, Francis Bacon's Three Studies of Lucian Freud sold for US$142.4 million (including the buyer's premium) to an unnamed buyer, nominally becoming the most expensive work of art ever to be sold at auction.[63][64][65][66]

- On 11 May 2015, Pablo Picasso's Les Femmes d'Alger ("Version O") sold for US$179.3 million to an unnamed buyer, becoming the most expensive work of art ever to be sold at auction at Christie's New York. In November of the same year, Amedeo Modigliani's Nu Couché (1917–18) sold at Christie's in New York for $170.4 million, making it the second most expensive work sold at auction.[67]

- In May 2016, the Oppenheimer Blue diamond sold for 56.837 million SFr, a record price for a jewel at auction.[68]

- On 7 July 2016, the highest price ever sold for an old master painting at Christie's was achieved with £44,882,500 / $58,167,720 / €52,422,760 for Rubens' Lot and his Daughters.[69][70]

- On 11 November 2017, a Patek Philippe Titanium wristwatch Ref. 5208T-010 was sold for 6.226 million US dollars (CHF 6,200,000) in Geneva, making it one of the most expensive watches ever sold at auction.[71][72]

- On 15 November 2017, Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi sold for a record $450.3 million (including buyer's premium).[73]

- On 4 July 2019, a bust fragment of Tutankhamun was sold for £4.7 million.[74] The Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities had tried to stop the auction, citing concerns that the bust had been looted from a temple and illegally taken from Egypt in the 1970s.[75]

- On June 25, 2020, Christie's sold a Timurid Quran manuscript, described as "rare and breathtaking", for £7 million (with fees), ten times its estimate.[76][77] The price was the highest price ever paid for a Quran manuscript.[76][77] Probably created at a Timurid prince's court, the manuscript comprised 534 folios of Arabic calligraphy on "gold-flecked, coloured paper from Ming China". The sale was criticized that since the "object apparently has no provenance prior to the 1980s, we can’t know anything about the context in which it was removed from its country of origin."[76]

Criticism

Insufficient or invalid provenance for auctioned artifacts

Christie's has been criticized for "an embarrassing history of a lack of transparency around provenance".[76] In May 2020, Hobby Lobby sued the auction house for its sale of a Gilgamesh tablet, allegedly while knowing it had a fake provenance.[78] In June 2020, they were forced to withdraw four Greek and Roman antiquities from sale after it was discovered that they came from "sites linked to convicted antiquities traffickers".[76][79] The same month, they were criticized for putting up a Benin plaque and two Igbo alusi figures for auction.[80][81] The plaque was tied to similar plaques taken from Nigeria during the Benin Expedition of 1897 and remained unsold after an auction was held.[81] The alusi figures are alleged to have been taken from Nigeria during the Nigerian Civil War and were sold for €212,500 (after fees), below their low estimate of €250,000.[81][82] Christie's claims to require "verifiable documented provenance that the object was taken out of its source nation prior to the earlier date of 2000, or the date which is legally applicable between the country in which the sale takes place and the source nation".[81]

Christie's Fine Art Storage Services (CFASS)

Christie's first ventured into storage services for outside clients in 1984, when it opened a 100,000 square feet brick warehouse in London that was granted "Exempted Status" by HM Revenue and Customs,[83] meaning that property may be imported into the United Kingdom and stored without incurring import duties and VAT. Christie's Fine Art Storage Services, or CFASS, is a wholly owned subsidiary that runs Christie's storage operation.

In September 2008, Christie's signed a 50-year lease on an early 1900s warehouse of the historic New York Dock Company[84] in Red Hook, Brooklyn, and subsequently spent $30 million converting it into a six-storey, 250,000 square feet[85] art-storage facility.[83] The facility opened in 2010 and features high-tech security and climate controls that maintain a virtually constant 70° and 50% relative humidity.[86]

Located near the Upper Bay tidal waterway near the Atlantic Ocean, the Brooklyn facility was hit by at least one storm surge during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. CFASS subsequently faced client defections and complaints arising from damage to works of art.[84] In 2013, AXA Art Insurance filed a lawsuit in New York court alleging that CFASS' "gross negligence" during the hurricane damaged art collected by late cellist Gregor Piatigorsky and his wife Jacqueline Rebecca Louise de Rothschild.[87] Later that year, StarNet Insurance Co., the insurer for the LeRoy Neiman Foundation and the artist's estate, also filed a lawsuit in New York Supreme Court claiming that the storage company's negligence caused more than $10 million in damages to Neiman's art.[88]

Ventures

Christie's Education offers graduate programmes in London and New York, and non-degree programmes in London, Paris, New York and Melbourne.[89]

With Bonhams, Christie's is a shareholder in the London-based Art Loss Register, a privately owned database used by law enforcement services worldwide to trace and recover stolen art.[90]

References

- "Christie's locations". Christies.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- "Christie's". Groupe Artémis. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012.

- "Christie's Sales Fall 5% as 'Froth' Comes off Global Art Market". 26 January 2016 – via www.bloomberg.com.

- Ellis-Petersen, Hannah; Brown, Mark (16 November 2017). "How Salvator Mundi became the most expensive painting ever sold at auction" – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Christies.com – About Us". Retrieved 3 December 2008.

James Christie conducted the first sale in London on 5 December 1766.

- Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser (London, England), 25 September 1762; Issue 10460

- M.A. Michael (2019). "Not Exactly a Connoisseur A New Portrait of James Christie". The British Art Journal (London: Robin Simon). 19:76.

- Sarah Lyall (27 February 1998), Jo Floyd, 74; Led Growth and Change at Christie's The New York Times.

- Carol Vogel (11 February 1997), At the Wire, Auction Fans, It's, It's . . . Christie's! The New York Times.

- Rita Reif (12 March 1990), Christie's Reverses Stand on Price Guarantees The New York Times.

- Carol Vogel (6 May 1998), Frenchman Gets Big Stake In Christie's The New York Times.

- Carol Vogel (19 May 1998), Frenchman Seeks the Rest Of Christie's The New York Times.

- Carol Vogel (19 February 1998), Christie's Ends Talks On Takeover By Swiss The New York Times.

- Carol Vogel (22 June 2001), Re: Real Estate The New York Times.

- Scott Reyburn (17 July 2012), Rothko, Private Sales Help Boost Christie's Revenue 13% Bloomberg.

- Rohleder, Anna (2001). "Who's Who in the Sotheby's Price-Fixing Trial". Forbes. New York. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- Mason, Christopher (3 May 2005). Art of the Steal: Inside the Sotheby's-Christie's Auction House Scandal. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-4406-0480-5.

- "Going Once, Going Twice… Glamour, Greed and Fraud at Sotheby's and Christie's". Knowledge@Wharton. University of Pennsylvania. 8 September 2004. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- Souren Melikian (17 January 2004), The battle of Paris: Christie's rising International Herald Tribune.

- Souren Melikian (12 January 2007), How Christie's kept top spot over Sotheby's in 2006 sales The New York Times.

- Judd Tully (24 October 2011), Private Sales Go Public: Why Christie's and Sotheby's Are Embracing Galleries Like Never Before The New York Observer.

- Colin Gleadell (27 February 2007), Christie's move stuns dealers The Daily Telegraph.

- Kate Taylor (16 April 2007), Auction Houses Vs. Dealers New York Sun.

- Walsh, Kate (28 December 2008). "Pinault woes may force Château Latour sell-off". (London) Sunday Times. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- Werdigier, Julia (12 January 2009). "Christie's Plans Cuts as Auctions Slow". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- Holson, Laura M. (8 February 2009). "In World of High-Glamour, Low-Pay Jobs, the Recession Has Its Bright Spots". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- "Christie's Resumes Cutting Jobs After May N.Y. Auctions Decline". Bloomberg News. 18 June 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- Vogel, Carol (18 June 2009). "Christie's Executive Leaves a Top Post". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- Pogrebin, Robin (14 December 2016). "Christie's Chief Executive to Step Down and Hand Reins to Guillaume Cerutti" – via NYTimes.com.

- "Christie’s Names Barbizet First Woman CEO as Murphy Exits". Bloomberg. Retrieved 14 May 2015

- "Christie's CEO Steven Murphy will step down". Fortune. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Georgina Adam (17 October 2012), Battle for private selling shows Archived 23 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

- Childs, Mary (26 January 2016). "'Curated' auctions and new buyers keep Christie's in the frame". Financial Times. ISSN 0307-1766. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- Scott Reyburn (8 March 2017), Christie’s to Close a London Salesroom and Scale Back in Amsterdam The New York Times.

- Carol Vogel (18 February 2013), Christie's Raises Its Commissions for First Time in Five Years The New York Times.

- Spero, Josh (9 March 2017). "Christie's to close South Kensington sale room". Financial Times.

- Media, ATG. "Christie's South Kensington to close sooner than expected". www.antiquestradegazette.com.

- https://www.nytimes.com/1977/05/15/archives/the-london-art-market-arrives-the-british-art-auctioneers-are.html

- https://www.nytimes.com/1976/09/30/archives/new-jersey-pages-christies-will-open-new-york-galleries-christies.html

- Carol Vogel (25 March 1997), Rockefeller Center Lease Is Signed By Christie's The New York Times.

- Irene Lacher (2 August 1996), Christie's Ups the Ante With Beverly Hills Space Los Angeles Times.

- Gabriella Angeleti (9 February 2017), Christie’s to open new flagship location in Los Angeles The Art Newspaper.

- Country Life (27 December 2016). "1848: the Stowe sale". Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Country Life (28 December 2016). "1882: the Hamilton Palace sale". Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Kimmelman, Michael (3 June 1989). "The Getty Fills a Role, for Itself and the Public". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- "Christie, Manson and Woods, sale 8030, 11 November 1994". Christies.com. 11 November 1994. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- "Stradivarius tops auction record". BBC News. 17 May 2006. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- Vogel, Carol (9 November 2006). "$491 Million Sale at Christie's Shatters Art Auction Record". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- "Bulgaria, Christie's Face Off Over Looted Artifact". Art Info. 7 November 2006. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Kodzhabasheva, Ani (7 June 2011). "Rogue excavators routinely steal and destroy Bulgaria's archaeological treasures". The Oxonian Globalist. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- "Christie's". Studiospecial.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- "Most expensive Gundam picture sold in history". People's Daily. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- "Ink painting of Gundam sold at historical price". Gamebase.com.tw. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- Lim, Le-Min (25 May 2008). "Gun-Slinging Robot, Wooden Beams Mark Quiet Hong Kong Art Sale". Bloomberg. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- Artefact (26 May 2008). "Gundam Fetches $600,000". Sankakucomplex.com. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- "Gundam Painting Auctioned for US$600,000+ in Hong Kong". Animenewsnetwork.com. 24 February 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- "Record-breaking YSL auction shrugs off crisis". Reuters. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- Erlanger, Steve (23 February 2009). "Yves Saint Laurent Art Sale Brings In $264 Million". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- "Small brown armchair sells for £19 million". The Daily Telegraph. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Harris, George (2 March 2009). "China demands return of Christie's 'looted relics'". France 24. Agence France-Presse (AFP). Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- "Marathon cup from 1896 sets Olympics auction record". Reuters. 18 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- "NYC Auction of George Washington Document Sets Record". CBS News New York. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- Vogel, Carol (12 November 2013). "At $142.4 Million, Triptych Is the Most Expensive Artwork Ever Sold at an Auction". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- Sherwin, Adam (13 November 2013). "When Lucian met Francis: Relationship that spawned most expensive painting ever sold". The Independent. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "Bacon painting fetches record price". BBC. 12 November 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- Swaine, Jon (13 November 2013). "Francis Bacon triptych smashes art auction record". Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "Contemporary art market cools, but Modern sector heats up at Christie's in 2015". theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- "Oppenheimer Blue diamond sells for world record at auction". The Guardian. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- Alain Truong art blog

- 6010107 Christie's sale record

- "PATEK PHILIPPE (REFERENCE 5208T-010 REFERENCE 5208T-010 WAS CREATED SPECIALLY FOR ONLY WATCH 2017)". www.christies.com. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Besler, Carol. "Christie's ONLY Watch Charity Auction Totals $10.8-Million, Including A $6-Million Patek Philippe". Forbes. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Leonardo da Vinci painting 'Salvator Mundi' sold for record $450.3 million".

- "'Stolen' Tutankhamun bust sells for £4.7m". BBC News. 4 July 2019.

- Michaelson, Ruth (10 June 2019). "Egypt tries to stop sale of Tutankhamun statue in London". The Guardian.

- Rice, Stephennie Mulder and Yael. "The mystery of the Timurid Qur'an". Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Quran quietly sells for record £7m despite questions over its provenance". www.theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Hobby Lobby sues Christie's for selling it an antiquity authorities say was looted". www.theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Christie's withdraws 'looted' Greek and Roman treasures". the Guardian. 14 June 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Obi-Young, Otosirieze. "Art Historian Chika Okeke-Agulu Calls for Cancellation of Paris Auction of Igbo Sculptures". Folio Nigeria. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- "Waning market for African artefacts? Controversial Benin bronze fails to sell at Christie's". www.theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Christie's Paris Sells Two 'Sacred Sculptures' From Nigeria, Despite Protests From Scholars and Nigerian Heritage Authorities". artnet News. 29 June 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Kelly Crow (26 April 2010), The Ultimate Walk-In Closet: Christie's Offers Art Storage in Brooklyn The Wall Street Journal.

- Laura Gilbert (26 April 2013), An exodus from Red Hook The Art Newspaper.

- Diane Cardwell (24 August 2009), A High-Tech Home for Multimillion-Dollar Works of Art The New York Times.

- Jennifer Maloney (10 May 2013), Builder Is Bullish on New York City's Fine-Art Storage Market: Developer Starts Construction of Art Storage Facility in Long Island City The Wall Street Journal.

- Laura Gilbert (20 August 2013), Axa sues Christie's storage services over Sandy damage The Art Newspaper.

- Laura Gilbert (12 December 2013), Christie's storage hit by second lawsuit over storm damage The Art Newspaper.

- Karen W. Arenson (20 October 2005), Getting a Master's Looking at the Masters The New York Times.

- The Art Loss Register, Ltd.: "The Art Loss Register is the world's largest database of stolen art and antiques dedicated to their recovery. Its shareholders include Christie's, Bonhams, members of the insurance industry and art trade associations. " Retrieved 27 September 2008.

Bibliography

- J. Herbert, Inside Christie's, London, 1990 (ISBN 978-0340430439)

- P. A. Colson, The Story of Christie's, London, 1950

- H. C. Marillier, Christie's, 1766–1925, London, 1926

- M. A. Michael, A Brief History of Christie's Education... , London, 2008 (ISBN 978-0955780707)

- W. Roberts, Memorials of Christie's, 2 vols, London, 1897

- "Going Once." Phaidon Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0-7148-7202-5.

External links

Media related to Christie's at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Christie's at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Christie's Education Graduate Programmes official website

- Christie's International Real Estate – Luxury Properties and Estates official website

- Christie's page on Arcadja Art database with several auction catalogs

- Bill Brooks – Daily Telegraph obituary

- Christie's Fine Art Storage Services – Official website