Love Jihad

Love Jihad, also known as Romeo Jihad,[5] is a conspiracy theory,[13] developed by proponents of Hindutva,[17] purporting that Muslim men target Hindu women for conversion to Islam by means such as seduction,[20] feigning love,[22] deception,[23] kidnapping,[26] and marriage,[29] as part of a broader "war" by Muslims against India,[31] and an organised international conspiracy,[34] for domination through demographic growth and replacement.[38]

| Part of a series on |

| Islamophobia |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

The conspiracy theory is noted for its similarities with Nazi themes of Jewish world domination,[9] and white nationalist conspiracy theories,[39] resembling Euro-American Islamophobia,[6] and featuring orientalist portrayals of Muslims as barbaric and hypersexual.[21] In addition, it covers paternalistic and patriarchal themes which bases itself on the assumption that women are possessions of men, whose purity is defiled as an equivalent to territorial conquest and hence need to be controlled and protected from Muslims, regardless of consent.[42] It has consequently been the cause of vigilante assaults, murders and other violent incidents,[43] including the Muzaffarnagar riots.[45]

Created in 2009,[46] as part of a propaganda campaign, the theory was disseminated by Hindutva publications such as the Sananta Prabhat and Hindu Janajagruti Samiti calling Hindus to protect their women from Muslim men who were simultaneously depicted as charming individuals and lecherous rapists.[10] Organisations like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the Vishva Hindu Parishad are since credited for its proliferation in India and abroad respectively.[47] The theory was noted to have become a significant belief in the state of Uttar Pradesh by 2014 and contributed to the success of the Bharatiya Janata Party campaign in the state.[8]

The concept was institutionalised in India after the election of the Bharatiya Janata Party led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.[48] Right wing pro government television media such as Times Now and Republic TV, and social media disinformation campaigns are generally held responsible for the growth of its popularity.[6] Legislation against the purported conspiracy have been initiated in a number of states ruled by the party and implemented in the state of Uttar Pradesh by the Yogi Adityanath government, where they have been used as a means of state repression on Muslims and crackdown on interfaith marriages.[50]

The theory has been adopted by the 969 Movement in Myanmar as an allegation of Islamisation of Buddhist women and used by the Tatmadaw as justification for military operations against Rohingya civilians.[53] It has extended among the non-Muslim Indian diaspora and led to formation of alliances between Hindutva groups and Western far right organisations such as the English Defence League.[6]

Background

Regional historical tensions

In a piece picked up by the Chicago Tribune, Foreign Policy correspondent Siddhartha Mahanta reports that the modern Love Jihad conspiracy has roots in the 1947 partition of India.[54] This partition led to the creation of India and Pakistan. The creation of two countries with different majority religions led to large-scale migration, with millions of people moving between the countries and rampant reports of sexual predation and forced conversions of women by men of both faiths.[54][55][56] Women on both sides of the conflict were impacted, leading to "recovery operations" by both the Indian and Pakistani governments of these women, with over 20,000 Muslim and 9,000 non-Muslim women being recovered between 1947 and 1956.[56] This tense history caused repeated clashes between the faiths in the decades that followed as well, according to Mahanta, as cultural pressure against interfaith marriage for either side.[54]

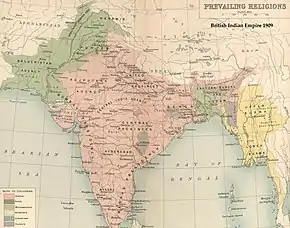

As of 2014, Hindus were the leading religious majority in India, at 81%, with Muslims at 13%.[57]

Marriage traditions and customs

India has a long tradition of arranged marriages, wherein the bride and groom do not choose their partners. Through the 2000s and 2010s, India witnessed a rise in love marriages, although tensions continue around interfaith marriages, along with other traditionally discouraged unions.[58][59] In 2012, The Hindu reported that illegal intimidation against consenting couples engaging in such discouraged unions, including inter-religious marriage, had surged.[60] That year, Uttar Pradesh saw the proposal of an amendment to remove the requirement to declare religion from the marriage law in hopes of encouraging those who were hiding their interfaith marriage due to social norms to register.[58]

One of the tensions surrounding interfaith marriage relates to concerns of required, even forced, marital conversion.[59][61] Marriage in Islam is a legal contract with requirements around the religions of the participants. While Muslim women are only permitted within the contract to marry Muslim men, Muslim men may marry "People of the Book", interpreted by most to include Jews and Christians, with the inclusion of Hindus disputed.[62] According to a 2014 article in the Mumbai Mirror, some non-Muslim brides in Muslim-Hindu marriages convert, while other couples choose a civil marriage under the Special Marriage Act of 1954.[59] Marriage between Muslim women Hindu men (including Sikh, Jaina and Buddhist) is legal civil marriage under The Special Marriage Act of 1954.

Hindu Nationalism and Right Wing Politics

Love jihad in politics has been closely tied to Hindu nationalism, particularly the more extremist form hindutva associated with BJP Prime minister of India Narendra Modi.[44] The anti-islamic stances of many right wing hindutva groups like Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) are usually hostile to inter-religious marriage and religious pluralism, which can sometimes result in mob violence motivated by allegations of love jihad.[63]

History

20th century

Similar controversies over inter religious marriage were relatively common in India from the 1920s until independence in 1947, when allegations of forced marriage were typically called "abductions".[64] They were more common in religiously diverse areas, including campaigns against both Muslims and Christians, and were tied to fears over religious demographics and political power in the newly emerging Indian nation. Fears of women converting was also a catalyst of the violence against women that occurred during that period.

2000s

Allegations of Love Jihad first rose to national awareness in September 2009.[65] Love Jihad was initially alleged to be conducted in Kerala and Mangalore in the coastal Karnataka region. According to the Kerala Catholic Bishops Council, by October 2009 up to 4,500 girls in Kerala had been targeted, whereas Hindu Janajagruti Samiti claimed that 30,000 girls had been converted in Karnataka alone.[66][67][68] Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana general secretary Vellapally Natesan said that there had been reports in Narayaneeya communities of "Love Jihad" attempts.[69][70] Reports of similar activities have also emerged from Pakistan and the United Kingdom.[71][72] According to an opinion piece by Liberal Politics blogger Sunny Hundal, "In the 90s, an anonymous leaflet (suspected to be by Hizb ut-Tahrir followers) urged Muslim men to seduce Sikh girls to convert them to Islam."[73]

The Sikh Council received reports in 2014 that girls from British Sikh families were becoming victims of Love Jihad. Furthermore, these reports stated that these girls were being exploited by their husbands, some of whom afterwards abandoned them in Pakistan. According to the Takht jathedar, "The Sikh council has rescued some of the victims (girls) and brought them back to their parents."[74]

The fundamentalist Muslim organization Popular Front of India and the Campus Front have been accused of promoting this activity.[75][76] In Kerala, some movies have been accused of promoting Love Jihad, a charge which has been denied by the filmmakers.[77]

Following the controversy's initial flare-up in 2009, it flared again in 2010, 2011 and 2014.[78][79][80] On 25 June 2014, Kerala Chief Minister Oommen Chandy informed the state legislature that 2667 young women were converted to Islam in the state since 2006. However, he stated that there was no evidence for any of them being forced conversions, and that fears of Love Jihad were "baseless."[80]

The discourses of Love Jihad are also prevalent in Myanmar.[81] Wirathu, the leader of 969 Movement, has said that Muslim men pretend to be Buddhists and then the Buddhist women are lured into Islam in Myanmar.[82][83] He has urged to "protect our Buddhist women from the Muslim love-jihad" by introducing further legislation.[84]

2009

Various organisations have joined together against this perceived conduct. Christian groups, such as the Christian Association for Social Action, and the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) banded against it, with the VHP establishing the Hindu Helpline that it indicates answered 1,500 calls in three months related to "Love Jihad".{{refn|[85] The Union of Catholic Asian News (UCAN) has reported that the Catholic Church is concerned about this alleged phenomenon.[86] The Vigilance Council of the Kerala Catholic Bishops' Council (KCBC) raised an alert for the Catholic community against the practice.[66] In September, posters appeared in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala under the name of right-wing group Shri Ram Sena warning against "Love Jihad".[87] The group announced in December that it would launch a nationwide "Save our daughters, save India" campaign to combat "Love Jihad".[88]

Muslim organizations in Kerala called it a malicious misinformation campaign.[89] Popular Front of India (PFI) committee-member Naseeruddin Elamaram denied that the PFI was involved in any "Love Jihad", stating that people convert to Hinduism and Christianity as well and that religious conversion is not a crime.[86] Members of the Muslim Central Committee of Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts have responded by claiming that Hindus and Christians have fabricated these claims to undermine the Muslim faith and community.[90]

2010

In July 2010, the "Love Jihad" controversy resurfaced in the press when Kerala Chief Minister V. S. Achuthanandan referenced the alleged matrimonial conversion of non-Muslim girls as part of an effort to make Kerala a Muslim majority state.[78][91] PFI dismissed his statements due to the findings of the Kerala probe,[91] but the president of the BJP Mahila Morcha, the women's wing of the conservative Bharatiya Janata Party, called for an NIA investigation, alleging that the Kerala state probe was closed prematurely due to a tacit understanding with PFI.[92] The Congress Party in Kerala responded strongly to the Chief Minister's comments, which they described as deplorable and dangerous.[78]

2011

In December 2011, the controversy erupted again in Karnataka legislative assembly, when member Mallika Prasad of the Bharatiya Janata Party asserted that the problem was ongoing and unaddressed – with, according to her, 69 of 84 Hindu girls who had gone missing between January and November of that year confessing after their recovery that "they'd been lured by Muslim youths who professed love."[79] According to The Times of India, response was divided, with Deputy Speaker N. Yogish Bhat and House Leader S. Suresh Kumar supporting governmental intervention, while Congress members B. Ramanath Rai and Abhay Chandra Jain argued that "the issue was being raised to disrupt communal harmony in the district."[79]

2014

During the resurgence of the controversy in 2014, protests turned violent at growing concern, even though, according to Reuters, the concept was considered "an absurd conspiracy theory by mainstream, moderate Indians."[93] BJP MP Yogi Adityanath alleged that Love Jihad was an international conspiracy targeting India,[94] announcing on television that the Muslims "can't do what they want by force in India, so they are using the love jihad method here."[57] Conservative Hindu activists have cautioned women in Uttar Pradesh to avoid Muslims and not to befriend them.[57] In Uttar Pradesh, the influential committee Akhil Bharitiya Vaishya Ekta Parishad announced their intention to push to restrict the use of cell phones among young women to prevent their being vulnerable to such activities.[95]

Following this announcement, The Times of India reported, Senior Superintendent of Police Shalabh Mathur "said the term 'love jihad' had been coined only to create fear and divide society along communal lines."[95] Muslim leaders have referred to 2014 rhetoric around the alleged conspiracy as a campaign of hate.[57] Feminists voiced concerns that efforts to protect women against the alleged activities would negatively impact women's rights, depriving them of free choice and agency.[59][96][97][98]

In September 2014, controversial BJP MP Sakshi Maharaj claimed that Muslim boys in madrasas are being motivated for Love Jihad with proposals of rewards of, "Rs 11 lakh for an "affair" with a Sikh girl, Rs 10 lakh for a Hindu girl and Rs 7 lakh for a Jain girl." He claimed to know this through reports to him by Muslims and by the experiences of men in his service who had converted for access.[99] Abdul Razzaq Khan, the vice-president of Jamiat Ulama Hind, responded by denying such activities, labeling the comments "part of conspiracy aimed at disturbing the peace of the nation" and demanding action against Maharaj.[100] Uttar Pradesh minister Mohd Azam Khan indicated the statement was "trying to break the country".[101]

2015

In January, Vishwa Hindu Parishad's women's wing, Durga Vahini used actor Kareena Kapoor's morphed picture half covered with burqa issue of their magazine, on the theme of Love Jihad.[102] The caption underneath read: "conversion of nationality through religious conversion".[103]

2017

In May 2017, the Kerala High Court annulled a marriage of a converted Hindu woman Akhila alias Hadia to a Muslim man Shafeen Jahan on the grounds that the bride's parents were not present, nor gave consent for the marriage, after allegations by her father of conversion and marriage at the behest of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. It ordered the director general of police of Kerala to investigate cases of "love jihad" and probe incidents of forced conversion, emphasising "the existence of an organisational setup functioning behind the scenes of such cases of 'love jihad' and conversions." The decision was apparently taken based on large number of radicalised youths from Kerala joining ISIS. It also observed, "Are there any radical organisations involved, are questions that plague an inquisitive mind. But sadly, there are no answers available in this case."[104] The father had claimed that his daughter had been radicalised and influenced to marry a Muslim man by some organisations so she no longer remained in her parents' custody.[105]

The woman's father, Ashokan Mani, had earlier filed a habeas corpus petition in January 2016 after she disappeared from the campus where she studied. He alleged his daughter was forcefully converted to Islam, and his family were reportedly told by her that she was being held against her will by two of her classmates Jaseena Aboobacker and her sister Faseena. However, after she was found, Akhila claimed that she was following Islam since 2012 and left her home of her own will. She also stated that she was not under any confinement against her free will. She stated that she had come under the religion's influence after hearing its teachings from her roommates. She said that she had joined a course run by Tharibathul Islam Sabha, Kottakkal to learn Islam. In her affidavit, she stated she lived with Aboobacker for a brief period and then shifted to Satyasarani's hostel in Manjeri, an institution allegedly promoting conversion to Islam and reported to be closely connected with the Popular Front of India. The institution introduced her to Sainaba in Ernakulam with whom she lived after her father filed the petition. The court allowed her to stay with Sainaba and later dismissed Ashokan's petition in June 2016, after she produced records of her admission to Satyasarani. Two months later, he filed another petition and alleged that his daughter was converted at the behest of ISIS and feared she may be taken to join it in Afghanistan, citing cases of two Kerala women joining the group after conversion and marriage to Muslim men. By December, Akhila had married Shafeen and Ashokan's petition came up for hearing in January 2017. Akhila showed the marriage certificate and marriage registration certificate, but it was annulled.[104][105]

The decision of the court was challenged by Shafeen Jahan in the Supreme Court of India in July 2017.[105] Shafin had met her with his family in August 2016 in response to her advertisement on a matrimonial website.[106] The Supreme Court began hearing the case on 4 August 2017. The counsel of the father of the woman alleged she had been psychologically indoctrinated.[107] The Supreme Court meanwhile sought response from the National Investigating Agency (NIA) and the Kerala government.[108] It ordered a NIA probe headed by former SC Judge R. V. Raveendran on 16 August while the NIA had earlier submitted that the woman's conversion and marriage was not "isolated" and it had detected a pattern emerging in the state, stating they came across another case involving the same people.[109] The NIA has stated that the husband in this case was allegedly in touch with two individuals charged in another Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant-related case and that one of these individuals may have coordinated the marriage.[110]

The Supreme Court on 8 March 2018 overturned the annulment of Hadiya's marriage by the Kerala High Court and held that the she had married of her own free will. However, it allowed NIA to continue investigation into the allegations of a terror dimension.[111]

2018

In June 2018, Jharkhand High Court granted a divorce in an alleged love jihad case in which the accused lied about his religion and forcing the victim to convert to Islam after marriage.[112]

2020

Despite drawing severe criticisms, the Syro Malabar Church continued to repeat its stand on ‘love jihad’. According to the church, Christian women are being targeted, recruited to terrorist outfit Islamic State, making them sex slaves and even killed. Detailing this, a circular, issued by Church chief Cardinal Mar George Alencherry, was read out in many parishes at the Sunday mass.[113][114]

In the circular (dated January 15) that was read out in churches on Sunday, it is stated that Christian women are being targeted under a conspiracy through inter-religious relationships, which often grow as a threat to religious harmony. “Christian women from Kerala are even being recruited to Islamic State through this,” the circular read.[115] Further, Kerala Catholic Bishops Conference’s (KCBC) Commission for Social Harmony and Vigilance, claimed that there were 4,000 instances of “Love Jihad” between 2005 and 2012.[116]

In September 2020, Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath asked his government to come up with a strategy to prevent "religious conversions in the name of love" and even considered passing an ordinance for the same if needed.[117][118]

On September 27, 2020, protests erupted in India when graphic video showing a young Muslim man gunning down a 21-year-old Hindu woman in broad daylight outside her college campus went viral. The family of a 21-year-old girl student, who was shot dead by jilted lover and his associate outside her college in Faridabad, has echoed the "love jihad" conspiracy theory, saying that she was forced to convert and marry the accused.[119][120]

On 31 October, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath announced that a law to curb 'Love Jihad'[lower-alpha 1] would be passed by his government.

The Uttar Pradesh state cabinet cleared the ordinance on 24 November 2020 following which it was approved and signed by state Governor Anandiben Patel on 28 November 2020.[122][123]

On December Madhya Pradesh approved an anti conversion bill same to the Uttar Pradesh one.[124][125][126][127]

Laws against Love Jihad

As of 25 November 2020, four BJP-ruled states: Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana and Karnataka, were mulling laws designed to prevent "forcible conversions" through marriage, commonly referred to as "love jihad" laws.[128][129] The proposed law in Uttar Pradesh, which also includes provisions against "unlawful religious conversion," declares a marriage null and void if the sole intention was to "change a girl's religion" and both it and the draft bill in Madhya Pradesh propose sentences of up to 10 years in prison for those who break the law.[130][131]

The law in Uttar Pradesh was approved on November 28 as the Prohibition of Unlawful Religious Conversion Ordinance.

The law in Madhya Pradesh was approved on December.

Official investigations

National

In August 2017, the National Investigation Agency (NIA) stated that it had found a common mentor in some love jihad cases in August 2017.[132] According to a later article in The Economist, "Repeated police investigations have failed to find evidence of any organised plan of conversion. Reporters have repeatedly exposed claims of "love jihad" as at best fevered fantasies and at worst, deliberate election-time inventions."[133] According to the same report, the common theme regarding many claims of "love jihad" have been the frenzy objection to an interfaith marriage while "Indian law erects no barriers to marriages between faiths, or against conversion by willing and informed consent. Yet the idea still sticks, even when the supposed “victims” dismiss it as nonsense."[133]

Karnataka

In October 2009, the Karnataka government announced its intentions to counter "Love Jihad", which "appeared to be a serious issue".[134] A week after the announcement, the government ordered a probe into the situation by the CID to determine if an organised effort existed to convert these girls and, if so, by whom it was being funded.[135] One woman whose conversion to Islam came under scrutiny as a result of the probe was temporarily ordered to the custody of her parents, but eventually permitted to return to her new husband after she appeared in court, denying pressure to convert.[136][137] In April 2010, police used the term to characterize the alleged kidnapping, forced conversion and marriage of a 17-year-old college girl in Mysore.[138]

In late 2009, The Karnataka CID (Criminal Investigation Department) reported that although it was continuing to investigate, it had found no evidence that a "Love Jihad" existed.[139] In late 2009, Director-General of Police Jacob Punnoose reported that although the investigation would continue, there was no evidence of any organised attempt by any group or individual using men "feigning love" to lure women to convert to Islam.[139][140] They did indicate that many Hindu girls had converted to Islam of their own will.[141] In early 2010, the State Government reported to the Karnataka High Court that although many young Hindu women had converted to Islam, there was no organized attempt to convince them to do so.[141] According to The Indian Express, Sankaran's conclusion that "such incidents under the pretext of love were rampant in certain parts of the state" ran contrary to Central and state government reports.[142] A petition was also put before Sankaran to prevent the use of the terms "Love Jehad" and "Romeo Jehad", but Sankaran declined to overrule an earlier decision not to restrain media usage.[142] Subsequently, however, the High Court stayed further police investigation, both because no organised efforts had been disclosed by police probes and because the investigation was specifically targeted against a single community.[143][144] In early 2010, the State Government reported to the Karnataka High Court that although many young Hindu women had converted to Islam, there was no organized attempt to convince them to do so.[141] A petition was also put before Sankaran to prevent the use of the terms "Love Jehad" and "Romeo Jehad", but Sankaran declined to overrule an earlier decision not to restrain media usage.[142] Subsequently, however, the High Court stayed further police investigation, both because no organised efforts had been disclosed by police probes and because the investigation was specifically targeted against a single community.[143][144]

The Karnataka government stated in 2010 that although many women had converted to Islam, there was no organized attempt to convince them to do so.[141]

Kerala

Following the launching of a poster campaign in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, purportedly by organisation Shri Ram Sena, state police began investigating the presence of that organisation in the area.[87] In late October 2009, police addressed the question of "Love Jihad" itself, indicating that while they had not located an organisation called "Love Jihad", "there are reasons to suspect 'concentrated attempts' to persuade girls to convert to Islam after they fall in love with Muslim boys".[145][146] They documented unconfirmed reports of a foreign-funded network of groups encouraging conversion through the subterfuge, but noted that no organisations conducting such campaigns had been confirmed and no evidence had been located to support foreign financial aid.[147]

In November 2009, DGP Jacob Punnoose stated there was no organisation whose members lured girls in Kerala by feigning love with the intention of converting. He told the Kerala High Court that 3 out of 18 reports he received expressed some doubts about the tendency. However, in absence of solid proof the investigations were still continuing.[140] In December 2009, Justice K.T. Sankaran who refused to accept Punnoose's report concluded from a case diary that there were indications of forceful conversions and stated it was clear from police reports there was a "concerted effort" to convert women with "blessings of some outfits". The court while hearing bail plea of two accused in "love jihad" cases stated that there had been 3,000-4,000 such conversions in past four years.[148] The Kerala High Court in December 2009 stayed investigations in the case, granting relief to the two accused though it criticised police investigations.[149] The investigation was closed by Justice M. Sasidharan Nambiar following Punnoose's statements that no conclusive evidence could be found for existence of "love jihad".[143]

On 9 December 2009, Justice K T Sankaran for the Kerala High Court weighed in on the matter while hearing bail for Muslim youth arrested for allegedly forcibly converting two campus girls. According to Sankaran, police reports revealed the "blessings of some outfits" for a "concerted" effort for religious conversions, some 3,000 to 4,000 incidences of which had taken place after love affairs in a four-year period.[148] Sankaran "found indications of 'forceful' religious conversions under the garb of 'love'", suggesting that "such 'deceptive' acts" might require legislative intervention to prevent.[148]

In January 2012, Kerala police declared that Love Jihad was "[a] campaign with no substance", bringing legal proceedings instead against the website hindujagruti.org for "spreading religious hatred and false propaganda."[143][150] In 2012, after two years of investigation into the alleged love jihad, Kerala Police declared it as a "campaign with no substance". Subsequently, a case was initiated against the website where fake posters of Muslim organisations offering money to Muslim youths for luring and trapping women were found.[143]

In 2017, after the Kerala High Court ruled that a marriage of a Hindu woman to a Muslim man was invalid on the basis of love jihad, and an appeal was filed in the Supreme Court of India by the Muslim husband where court, based on the "unbiased and independent" evidence requested by the court from NIA, instructed NIA to investigate all similar cases for establishing the pattern of love jihad. It allowed NIA to explore all similar suspicious incidences to find whether banned organisations, such as SIMI, are preying on vulnerable Hindu women to recruit them as terrorists.[151][152][153][154] NIA had earlier submitted before the court that the case was not an "isolated" incident and it had detected a pattern emerging in the state, stating that another case involved the same people who acted as instigators.[109]

Uttar Pradesh

In September 2014, following the resurgence of national attention,[80] Reuters reported that police in Uttar Pradesh had found no credence in the five or six recent allegations of Love Jihad that had been brought before them, with state police chief A.L. Banerjee stating that, "In most cases we found that a Hindu girl and Muslim boy were in love and had married against their parents' will."[93] They reportedly indicated that "sporadic cases of trickery by unscrupulous men are not evidence of a broader conspiracy."[93]

That same month, the Allahabad High Court gave the government and election commission of Uttar Pradesh 10 days to respond to a petition to restrain the use of the word "Love Jihad" and to take action against Yogi Adityanath.[54][94][155]

Uttar Pradesh Police in September 2014 found no evidence of attempted or forced conversion in five of six reported cases of love jihad reported to them in past three months. Police said sporadic cases of trickery by unscrupulous men are not evidence of a broader conspiracy.[93]

See also

Notes

- As of November 2020,'Love jihad' is a term not recognized by the Indian legal system.[121]

References

- Khatun, Nadira (14 December 2018). "'Love-Jihad' and Bollywood: Constructing Muslims as 'Other'". Journal of Religion & Film. University of Nebraska Omaha. 22 (3). ISSN 1092-1311.

- Gupta, Charu (2009). "Hindu Women, Muslim Men: Love Jihad and Conversions". Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (51): 13–15. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 25663907 – via JSTOR.

- Rao, Mohan (1 October 2011). "Love Jihad and Demographic Fears". Indian Journal of Gender Studies. 18 (3): 425–430. doi:10.1177/097152151101800307. ISSN 0971-5215. S2CID 144012623 – via SAGE Journals.

- Khalid, Saif (24 August 2017). "The Hadiya case and the myth of 'Love Jihad' in India". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- [1][2][3][4]

- Farokhi, Zeinab (2020). "Hindu Nationalism, News Channels, and "Post-Truth" Twitter: A Case Study of "Love Jihad"". In Boler, Megan; Davis, Elizabeth (eds.). Affective Politics of Digital Media: Propaganda by Other Means. Routledge. pp. 226–239. ISBN 978-1-000-16917-1.

- Nair, Rashmi; Vollhardt, Johanna Ray (October 2019). "Intersectional Consciousness in Collective Victim Beliefs: Perceived Intragroup Differences Among Disadvantaged Groups". Political Psychology. Wiley. 40 (5): 917–934. doi:10.1111/pops.12593 – via ResearchGate.

- George, Cherian (2016). Hate Spin: The Manufacture of Religious Offense and Its Threat to Democracy. MIT Press. pp. 96–101. ISBN 978-0-262-33607-9.

- Zimdars, Melissa; McLeod, Kembrew (2020). Fake News: Understanding Media and Misinformation in the Digital Age. MIT Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-0-262-53836-7.

- Anand, D. (2011). Hindu Nationalism in India and the Politics of Fear. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 63–69. ISBN 978-0-230-60385-1.

- Purewal, Navtej K. (3 September 2020). "Indian Matchmaking: a show about arranged marriages can't ignore the political reality in India". The Conversation UK. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- Byatnal, Amruta (13 October 2013). "Hindutva vigilantes target Hindu-Muslim couples". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- [6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

- Sarkar, Tanika (1 July 2018). "Is Love without Borders Possible?". Feminist Review. 119 (1): 7–19. doi:10.1057/s41305-018-0120-0. ISSN 0141-7789. S2CID 149827310 – via SAGE Journals.

- Strohl, David James (2 January 2019). "Love jihad in India's moral imaginaries: religion, kinship, and citizenship in late liberalism". Contemporary South Asia. Taylor & Francis. 27 (1): 27–39. doi:10.1080/09584935.2018.1528209. ISSN 0958-4935. S2CID 149838857.

- Waikar, Prashant (2018). "Reading Islamophobia in Hindutva: An Analysis of Narendra Modi's Political Discourse". Islamophobia Studies Journal. 4 (2): 161–180. doi:10.13169/islastudj.4.2.0161. ISSN 2325-8381. JSTOR 10.13169/islastudj.4.2.0161 – via JSTOR.

- [6][14][15][16]

- Daniel, Rupam Jain Nair, Frank Jack (4 September 2014). "'Love Jihad' and religious conversion polarise in Modi's India". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020.

- Kazmin, Amy (4 December 2020). "Hindu nationalists raise spectre of 'love jihad' with marriage law". Financial Times.

- [8][10][18][19]

- Leidig, Eviane (26 May 2020). "Hindutva as a variant of right-wing extremism". Patterns of Prejudice. Taylor & Francis. 54 (3): 215–237. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2020.1759861. ISSN 0031-322X.

- [6][7][11][21]

- [18][16]

- Grewal, Inderpal (7 October 2014). "Narendra Modi's BJP: Fake Feminism and 'Love Jihad' Rumors". HuffPost. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- Banaji, Shakuntala (2 October 2018). "Vigilante Publics: Orientalism, Modernity and Hindutva Fascism in India". Javnost - the Public. Taylor & Francis. 25 (4): 333–350. doi:10.1080/13183222.2018.1463349. ISSN 1318-3222.

- [2][24][25]

- Ramachandran, Sudha (2020). "Hindutva Violence in India: Trends and Implications". Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses. 12 (4): 15–20. ISSN 2382-6444. JSTOR 26918077 – via JSTOR.

- Ravindran, Gopalan (2020). Deleuzian and Guattarian Approaches to Contemporary Communication Cultures in India. Springer Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 978-981-15-2140-9.

- [6][16][27][28]

- Chacko, Priya (March 2019). "Marketizing Hindutva: The state, society, and markets in Hindu nationalism". Modern Asian Studies. 53 (2): 377–410. doi:10.1017/S0026749X17000051. ISSN 0026-749X.

- [3][6][30]

- Punwani, Jyoti (2014). "Myths and Prejudices about 'Love Jihad'". Economic and Political Weekly. 49 (42): 12–15. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 24480870 – via JSTOR.

- Jayal, Niraja Gopal (2 January 2019). "Reconfiguring Citizenship in Contemporary India". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. Taylor & Francis. 42 (1): 33–50. doi:10.1080/00856401.2019.1555874. ISSN 0085-6401.

- [2][32][33]

- Gökarıksel, Banu; Neubert, Christopher; Smith, Sara (15 February 2019). "Demographic Fever Dreams: Fragile Masculinity and Population Politics in the Rise of the Global Right". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. University of Chicago Press. 44 (3): 561–587. doi:10.1086/701154. ISSN 0097-9740. S2CID 151053220.

- Maiorano, Diego (3 April 2015). "Early Trends and Prospects for Modi's Prime Ministership". The International Spectator. Taylor & Francis. 50 (2): 75–92. doi:10.1080/03932729.2015.1024511. ISSN 0393-2729. S2CID 155228179.

- Tyagi, Aastha; Sen, Atreyee (2 January 2020). "Love-Jihad (Muslim Sexual Seduction) and ched-chad (sexual harassment): Hindu nationalist discourses and the Ideal/deviant urban citizen in India". Gender, Place & Culture. Taylor & Francis. 27 (1): 104–125. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2018.1557602. ISSN 0966-369X. S2CID 165145583.

- [35][36][37]

- [9][35][21]

- Ravindran, Gopalan (2020). Deleuzian and Guattarian Approaches to Contemporary Communication Cultures in India. Springer Publishing. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-981-15-2140-9.

- Basu, Amrita (2 October 2018). "Whither Democracy, Secularism, and Minority Rights in India?". The Review of Faith & International Affairs. 16 (4): 34–46. doi:10.1080/15570274.2018.1535035. ISSN 1557-0274.

- [2][6][24][35][40][41]

- [12][16][25][27][33]

- Chandra Pandey, Manish; Pathak, Vikas (12 September 2013). "Muzaffarnagar: 'Love jihad', beef bogey sparked riot flames". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- [8][44]

- [10][35]

- [25][30]

- [6][16][35]

- Biswas, Soutik (8 December 2020). "Love jihad: The Indian law threatening interfaith love". BBC News. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- [19][49]

- Frydenlund, Iselin (2018). "Buddhist Islamophobia: Actors, Tropes, Contexts". Handbook of Conspiracy Theory and Contemporary Religion: 279–302. doi:10.1163/9789004382022_014. ISBN 9789004382022.

- Kingston, Jeff (2019). The Politics of Religion, Nationalism, and Identity in Asia. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 117–119. ISBN 978-1-4422-7688-8.

- [51][52]

- Mahanta, Siddhartha (5 September 2014). "India's Fake 'Love Jihad'". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- Bhavnani, Nandita (29 July 2014). The Making of Exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India. Westland. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-93-84030-33-9.

- Huynh, Kim; Bina D'Costa; Katrina Lee-Koo (30 April 2015). Children and Global Conflict. Cambridge University Press. pp. 274–275. ISBN 978-1-316-29876-3.

- Mandhana, Niharika (4 September 2014). "Hindu Activists in India Warn Women to Beware of 'Love Jihad'". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Indian Laws, Culture Boost Inter-Faith Marriages". Voice of America. 12 August 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- "Jihad in the time of love". Mumbai Mirror. 31 August 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- Dhar, Aarti (24 January 2012). "Law Commission's new draft wants khap panchayats on marriages declared illegal". The Hindu. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- "Two booked for forcing wives to embrace Islam in Madhya Pradesh". The Times of India. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- Cornell, Vincent J. (2007). Voices of Islam: Voices of life : family, home, and society. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 61. ISBN 9780275987350.

This includes Jew, Christians and Sabeans (a sect that most Muslims believe no longer exists). Zoroastrians, certain types of Hindus, and Buddhists are accepted by some Muslims as 'People of the Book' as well, but this is a matter of dispute.

- Sarkar, Tanika (1 July 2018). "special guest contribution: is love without borders possible?". Feminist Review. 119 (1): 7–19. doi:10.1057/s41305-018-0120-0. ISSN 1466-4380. S2CID 149827310.

- Banerjee, Chandrima. "Ram Sene coined 'love jihad', but first 'case' goes back a century | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- "'Love jihad' piqued US interest". The Times of India. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Beware of 'love jihad'". Mathrubhumi. Kochi, Kerala, India: mathrubhumi.org. 15 October 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- "Is 'Love Jihad' terror's new mantra?". Rediff. 14 October 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Mangalore: Eight Hindu Organisations to Protest Against 'Love Jehad'". Daijiworld.com. 14 October 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "SNDP to campaign against Love Jihad: Vellappally". Asianet. 19 October 2009. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- "SNDP to join fight against 'Love Jihad'". ExpressBuzz. 19 October 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- Yudhvir Rana (10 January 2011). "'Not just White girls, Pak Muslim men sexually target Hindu and Sikh girls as well". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Police protect girls forced to convert to Islam". This Is London. 22 February 2007. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- Sunny Hundal (3 July 2012). "EDL and Sikh men unite in using women as pawns | Sunny Hundal | Opinion". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- HT Correspondent (27 January 2014). "'Love jihad': UK Sikh girls' exploitation worries Takht". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Nelson, Dean (13 October 2009). "Handsome Muslim men accused of waging 'love jihad' in India". The Telegraph. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- Raghavan, B. S. (30 July 2010). "Kerala's demographic trends bear watching". The Hindu Business Line. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- Raj, Rohit (27 July 2012). "Filmmakers protest Love Jihad slur in social media". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- "Kerala CM criticised for speaking out against 'love jihad'". The Economic Times. 27 July 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- "Love jihad sparks hate". The Times of India. 17 December 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- "Over 2500 women converted to Islam in Kerala since 2006, says Oommen Chandy". India Today. 4 September 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- Marius Timmann Mjaaland (2019). Formatting Religion: Across Politics, Education, Media, and Law. Taylor & Francis. p. 89. ISBN 9780429638275.

- Kesavan Mukul. "South Asia: Murderous majorities".

- Iselin Frydenlund. "Buddhist Islamophobia: Actors, Tropes, Contexts".

- "Buddhist backlash against fear of 'love-jihad'". Bangkok Post. 2014.

- Ananthakrishnan G (13 October 2009). "'Love Jihad' racket: VHP, Christian groups find common cause". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Church, state concerned about ´love jihad´". Archived from the original on 18 October 2009. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Babu Thomas (26 September 2009). "Poster campaign against 'Love Jihad'". expressbuzz.com. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- "'Rama Sene to launch 'Save our daughters Save India'". The Times of India. 31 October 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "'Love Jihad' a misinformation campaign: Kerala Muslim outfits". The Times of India. 2 November 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "'Anti Muslim forces phrase 'Love Jihad". Sahilonline.org. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Kerala CM reignites 'love jihad' theory". The Times of India. 26 July 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- "Love jihad cases: Mahila Morcha for NIA probe". Express News Service. The New Indian Express Group. 25 July 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- Nair, Rupam Jain; Daniel, Frank Jack (5 September 2014). "'Love Jihad' and religious conversion polarise in Modi's India". Reuters. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Love Jihad: High Court asks UP govt, EC to file response". India TV. 4 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Mishra, Ishita (2 September 2014). "In UP, community bans mobiles for girls to fight 'love jihad'". The Times of India. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Saha, Abhishek (1 September 2014). "Amid rage over 'Love Jihad' what about what women want?". New Delhi. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Aravind, Indulekha (6 September 2014). "Love Jihad campaign treats women as if they are foolish: Charu Gupta". Business Standard. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Akram, Maria (29 August 2014). "Netas using love jihad as a tool for polarization". The Times of India. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- "BJP Unnao MP Sakshi Maharaj claims madrasas offering cash rewards for love jihad". The Indian Express. 15 September 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Muslim Cleric Blasts Sakshi Maharaj for Jihad Factory Remark". The Times of India. 17 September 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Azam slams Sakshi Maharaj on madarssa issue, calls him "rapist"". India TV News. 17 September 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Star Power Kareena Used As Warning Against Love Jihad". Hindustan Times. 7 January 2015.

- "Kareena Kapoor is now the face of VHP's love jihad campaign". India Today. 8 January 2015.

- "Kerala High Court nullifies woman's marriage with Muslim man after bride's father raises Islamic State angle". India Today. 25 May 2017.

- "Kerala Muslim man challenges HC decision to nullify marriage with Hindu woman over ISIS link". India Today. 6 July 2017.

- Rajagopal, Krishnadas (9 July 2017). "Voluntary marriage not love jihad: man's plea against Kerala HC ruling". The Hindu.

- "Supreme Court hears its 1st 'love jihad' case, demands proof from NIA". The Times of India. 4 August 2017.

- "Supreme Court Hears Case Of 'Love Jihad', Seeks Response From The NIA". Huffington Post. 4 August 2017.

- Rajagopal, Krishnadas (16 August 2017). "Supreme Court orders NIA probe into Kerala woman's conversion and marriage case". The Hindu.

- "Hadiya's 'husband' was in touch with IS men before their marriage: NIA". The Times of India. New Delhi: Bennett, Coleman & Co.Ltd. 4 December 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "Hadiya's marriage restored, Supreme Court says no love jihad". India Today. 8 March 2018.

- "Jharkhand love jihad case: Former national shooter Tara Shahdeo granted divorce from Raqibul Hassan". dnaindia. 27 June 2018.

- Raghunathan, Arjun (15 January 2020). "Kerala Church says Love Jihad is real, claims Christian women being lured into IS trap". Deccan Herald.

- "Love Jihad making Kerala girls sex slaves: Church". The Times of India. 16 January 2020.

- "Kerala Catholic churches read out 'love jihad' circular". The News Minute. 19 January 2020.

- "Christian girls targeted and killed in name of love jihad: Kerala's Syro-Malabar church". The Week. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- "Adityanath govt mulls ordinance against 'love jihad'". The Economic Times. 18 September 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- "Adityanath govt. mulls ordinance against 'love jihad'". The Hindu. PTI. 18 September 2020. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 19 September 2020.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "'Love jihad' protests erupt in India after video shows Hindu woman gunned down outside college". The Independent. 27 October 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- Joseph, Alphonse (27 October 2020). "Faridabad: Family members of deceased woman claims she was 'forced to convert, marry accused'". www.oneindia.com. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- "Adityanath Cabinet Approves Ordinance Against 'Love Jihad'". The Wire (India). 24 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- "Jail term, fine for 'illegal' conversions in Uttar Pradesh". The Hindu. Special Correspondent. 24 November 2020. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 25 November 2020.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "UP Governor Anandiben Patel gives assent to ordinance on 'unlawful conversion'". mint. 28 November 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- "India's Madhya Pradesh state now plans 'love jihad' law". www.aljazeera.com.

- "Madhya Pradesh to take ordinance route to enforce anti-conversion law". Deccan Herald. 28 December 2020.

- Scroll Staff. "'Love jihad': Madhya Pradesh Cabinet approves anti-conversion bill". Scroll.in.

- "Madhya Pradesh to enforce 'love jihad' ordinance". Hindustan Times.

- Trivedi, Upmanyu (25 November 2020). "India's Most Populous State Brings Law to Fight 'Love Jihad'". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- "After MP, Haryana Says a Committee Will Draft Anti-'Love Jihad' Law". The Wire (India). 18 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- "'Love jihad': Madhya Pradesh proposes 10-year jail term in draft bill". Scroll.in. 26 November 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Seth, Maulshree (26 November 2020). "UP clears 'love jihad' law: 10-year jail, cancelling marriage if for conversion". The Indian Express. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- "NIA finds a common mentor in Kerala 'love jihad' cases". The Times of India. New Delhi: Bennett, Coleman & Co.Ltd. 28 August 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- "India is working itself into a frenzy about interfaith marriages". The Economist. 30 September 2017.

- "Karnataka to take steps to counter 'Love Jihad' movement". Deccan Herald. 22 October 2009.

- "Govt directs CID to probe 'love jihad'". The Times of India. 27 October 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Love jihad: HC orders thorough probe by DGP". The Times of India. 22 October 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Woman denies 'love jihad', court lets her to go with lover". Thaindian News. 13 November 2009. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Love Jihad: girl rescued". The Times of India. 6 April 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Karnataka CID finds no evidence of 'Love Jihad'". The Hindu. 13 November 2009.

- "Kerala police have no proof on 'Love Jihad'". Deccan Herald. 11 November 2009.

- Staff Reporter (23 April 2010). "No love jihad movement in State'". The Hindu.

- "HC calls for law to check 'love jehad'". The Indian Express. 10 December 2009.

- Padanna, Ashraf (4 January 2012). "Kerala police probe crack 'love jihad' myth". The Gulf Today. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013.

- "Kerala cops fail to establish 'love jihad' conspiracy". Ibnlive. 23 December 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "No 'Love Jihad' in Kerala". Deccan Herald. 21 May 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Kerala HC wants probe into 'love jihad'". Indian Express.

- "DGP suspects presence of 'Love Jihad' in Kerala". Mathrubhumi.

- "Kerala HC asks govt to frame laws to stop 'love jihad'". The Economic Times. 10 December 2009.

- 'Love jihad': Kerala high court stays police investigation DNA News

- Wahab, Hisham ul (7 June 2018). "Kerala's 'Love Jihad' Incidents Haven't Ended With Hadiya". TheQuint.

- "Top Counter-Terror Agency, NIA, To Probe Kerala 'Love Jihad' Marriage.", NDTV, 16 August 2017.

- "NIA probe on 'love jihad' may cover all suspicious cases.", The Economic Times, 16 August 2017.

- "Supreme Court hears its 1st 'love jihad' case, demands proof from NIA", The Times of India, 5 August 2017.

- "Kerala 'Love Jihad' Case: NIA to Assess Ramifications on National Security." Archived 16 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, CNN News18, 10 August 2017.

- "'Love-jihad' row: Allahabad High Court issues notice to Centre, Uttar Pradesh government". DNA. 4 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

External links

Quotations related to Love Jihad at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Love Jihad at Wikiquote