Bermuda Triangle

The Bermuda Triangle, also known as the Devil's Triangle, is a loosely defined region in the western part of the North Atlantic Ocean where a number of aircraft and ships are said to have disappeared under mysterious circumstances. Most reputable sources dismiss the idea that there is any mystery.[1][2][3]

| Bermuda Triangle | |

|---|---|

| Devil's Triangle | |

One version of the Bermuda Triangle area | |

| Coordinates | 25°N 71°W |

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

The vicinity of the Bermuda Triangle is amongst the most heavily traveled shipping lanes in the world, with ships frequently crossing through it for ports in the Americas, Europe and the Caribbean islands. Cruise ships and pleasure craft regularly sail through the region, and commercial and private aircraft routinely fly over it.

Popular culture has attributed various disappearances to the paranormal or activity by extraterrestrial beings. Documented evidence indicates that a significant percentage of the incidents were spurious, inaccurately reported, or embellished by later authors.

Origins

The earliest suggestion of unusual disappearances in the Bermuda area appeared in a September 17, 1950, article published in The Miami Herald (Associated Press)[4] by Edward Van Winkle Jones.[5] Two years later, Fate magazine published "Sea Mystery at Our Back Door",[6][7] a short article by George Sand covering the loss of several planes and ships, including the loss of Flight 19, a group of five US Navy Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers on a training mission. Sand's article was the first to lay out the now-familiar triangular area where the losses took place, as well as the first to suggest a supernatural element to the Flight 19 incident. Flight 19 alone would be covered again in the April 1962 issue of American Legion magazine.[8] In it, author Allan W. Eckert wrote that the flight leader had been heard saying, "We are entering white water, nothing seems right. We don't know where we are, the water is green, no white." He also wrote that officials at the Navy board of inquiry stated that the planes "flew off to Mars."[9]

In February 1964, Vincent Gaddis wrote an article called "The Deadly Bermuda Triangle" in the pulp magazine Argosy saying Flight 19 and other disappearances were part of a pattern of strange events in the region.[10] The next year, Gaddis expanded this article into a book, Invisible Horizons.[11]

Other writers elaborated on Gaddis' ideas: John Wallace Spencer (Limbo of the Lost, 1969, repr. 1973);[12] Charles Berlitz (The Bermuda Triangle, 1974);[13] Richard Winer (The Devil's Triangle, 1974),[14] and many others, all keeping to some of the same supernatural elements outlined by Eckert.[15]

Triangle area

The Gaddis Argosy article delineated the boundaries of the triangle,[10] giving its vertices as Miami; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Bermuda. Subsequent writers did not necessarily follow this definition. Some writers gave different boundaries and vertices to the triangle, with the total area varying from 1,300,000 to 3,900,000 km2 (500,000 to 1,510,000 sq mi). "Indeed, some writers even stretch it as far as the Irish coast."[2] Consequently, the determination of which accidents occurred inside the triangle depends on which writer reported them.

Criticism of the concept

Larry Kusche

Larry Kusche, author of The Bermuda Triangle Mystery: Solved (1975)[1] argued that many claims of Gaddis and subsequent writers were exaggerated, dubious or unverifiable. Kusche's research revealed a number of inaccuracies and inconsistencies between Berlitz's accounts and statements from eyewitnesses, participants, and others involved in the initial incidents. Kusche noted cases where pertinent information went unreported, such as the disappearance of round-the-world yachtsman Donald Crowhurst, which Berlitz had presented as a mystery, despite clear evidence to the contrary. Another example was the ore-carrier recounted by Berlitz as lost without trace three days out of an Atlantic port when it had been lost three days out of a port with the same name in the Pacific Ocean. Kusche also argued that a large percentage of the incidents that sparked allegations of the Triangle's mysterious influence actually occurred well outside it. Often his research was simple: he would review period newspapers of the dates of reported incidents and find reports on possibly relevant events like unusual weather, that were never mentioned in the disappearance stories.

Kusche concluded that:

- The number of ships and aircraft reported missing in the area was not significantly greater, proportionally speaking, than in any other part of the ocean.

- In an area frequented by tropical cyclones, the number of disappearances that did occur were, for the most part, neither disproportionate, unlikely, nor mysterious.

- Furthermore, Berlitz and other writers would often fail to mention such storms or even represent the disappearance as having happened in calm conditions when meteorological records clearly contradict this.

- The numbers themselves had been exaggerated by sloppy research. A boat's disappearance, for example, would be reported, but its eventual (if belated) return to port may not have been.

- Some disappearances had, in fact, never happened. One plane crash was said to have taken place in 1937, off Daytona Beach, Florida, in front of hundreds of witnesses; a check of the local papers revealed nothing.

- The legend of the Bermuda Triangle is a manufactured mystery, perpetuated by writers who either purposely or unknowingly made use of misconceptions, faulty reasoning, and sensationalism.[1]

In a 2013 study, the World Wide Fund for Nature identified the world's 10 most dangerous waters for shipping, but the Bermuda Triangle was not among them.[17][18]

Further responses

When the UK Channel 4 television program The Bermuda Triangle (1992)[19] was being produced by John Simmons of Geofilms for the Equinox series, the marine insurance market Lloyd's of London was asked if an unusually large number of ships had sunk in the Bermuda Triangle area. Lloyd's determined that large numbers of ships had not sunk there.[3] Lloyd's does not charge higher rates for passing through this area. United States Coast Guard records confirm their conclusion. In fact, the number of supposed disappearances is relatively insignificant considering the number of ships and aircraft that pass through on a regular basis.[1]

The Coast Guard is also officially skeptical of the Triangle, noting that they collect and publish, through their inquiries, much documentation contradicting many of the incidents written about by the Triangle authors. In one such incident involving the 1972 explosion and sinking of the tanker V. A. Fogg, the Coast Guard photographed the wreck and recovered several bodies,[20] in contrast with one Triangle author's claim that all the bodies had vanished, with the exception of the captain, who was found sitting in his cabin at his desk, clutching a coffee cup.[12] In addition, V. A. Fogg sank off the coast of Texas, nowhere near the commonly accepted boundaries of the Triangle.

The Nova/Horizon episode The Case of the Bermuda Triangle, aired on June 27, 1976, was highly critical, stating that "When we've gone back to the original sources or the people involved, the mystery evaporates. Science does not have to answer questions about the Triangle because those questions are not valid in the first place ... Ships and planes behave in the Triangle the same way they behave everywhere else in the world."[2]

Skeptical researchers, such as Ernest Taves[21] and Barry Singer,[22] have noted how mysteries and the paranormal are very popular and profitable. This has led to the production of vast amounts of material on topics such as the Bermuda Triangle. They were able to show that some of the pro-paranormal material is often misleading or inaccurate, but its producers continue to market it. Accordingly, they have claimed that the market is biased in favor of books, TV specials, and other media that support the Triangle mystery, and against well-researched material if it espouses a skeptical viewpoint.

Benjamin Radford, an author and scientific paranormal investigator, noted in an interview on the Bermuda Triangle that it could be very difficult locating an aircraft lost at sea due to the vast search area, and although the disappearance might be mysterious, that did not make it paranormal or unexplainable. Radford further noted the importance of double-checking information as the mystery surrounding the Bermuda Triangle had been created by people who had neglected to do so.[23]

Hypothetical explanation attempts

Persons accepting the Bermuda Triangle as a real phenomenon have offered a number of explanatory approaches.

Paranormal explanations

Triangle writers have used a number of supernatural concepts to explain the events. One explanation pins the blame on leftover technology from the mythical lost continent of Atlantis. Sometimes connected to the Atlantis story is the submerged rock formation known as the Bimini Road off the island of Bimini in the Bahamas, which is in the Triangle by some definitions. Followers of the purported psychic Edgar Cayce take his prediction that evidence of Atlantis would be found in 1968, as referring to the discovery of the Bimini Road. Believers describe the formation as a road, wall, or other structure, but the Bimini Road is of natural origin.[24]

Other writers attribute the events to UFOs.[25][26] Charles Berlitz, author of various books on anomalous phenomena, lists several theories attributing the losses in the Triangle to anomalous or unexplained forces.[13]

Compass variations

Compass problems are one of the cited phrases in many Triangle incidents. While some have theorized that unusual local magnetic anomalies may exist in the area,[27] such anomalies have not been found. Compasses have natural magnetic variations in relation to the magnetic poles, a fact which navigators have known for centuries. Magnetic (compass) north and geographic (true) north are exactly the same only for a small number of places – for example, as of 2000, in the United States, only those places on a line running from Wisconsin to the Gulf of Mexico.[28] But the public may not be as informed, and think there is something mysterious about a compass "changing" across an area as large as the Triangle, which it naturally will.[1]

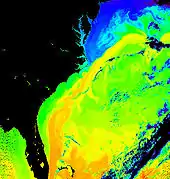

Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a major surface current, primarily driven by thermohaline circulation that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and then flows through the Straits of Florida into the North Atlantic. In essence, it is a river within an ocean, and, like a river, it can and does carry floating objects. It has a maximum surface velocity of about 2 m/s (6.6 ft/s).[29] A small plane making a water landing or a boat having engine trouble can be carried away from its reported position by the current.

Human error

One of the most cited explanations in official inquiries as to the loss of any aircraft or vessel is human error.[30] Human stubbornness may have caused businessman Harvey Conover to lose his sailing yacht, Revonoc, as he sailed into the teeth of a storm south of Florida on January 1, 1958.[31]

Violent weather

Hurricanes are powerful storms that form in tropical waters and have historically cost thousands of lives and caused billions of dollars in damage. The sinking of Francisco de Bobadilla's Spanish fleet in 1502 was the first recorded instance of a destructive hurricane. These storms have in the past caused a number of incidents related to the Triangle.

A powerful downdraft of cold air was suspected to be a cause in the sinking of Pride of Baltimore on May 14, 1986. The crew of the sunken vessel noted the wind suddenly shifted and increased velocity from 32 km/h (20 mph) to 97–145 km/h (60–90 mph). A National Hurricane Center satellite specialist, James Lushine, stated "during very unstable weather conditions the downburst of cold air from aloft can hit the surface like a bomb, exploding outward like a giant squall line of wind and water."[32] A similar event occurred to Concordia in 2010, off the coast of Brazil. Scientists are currently investigating whether "hexagonal" clouds may be the source of these up-to-170 mph (270 km/h) "air bombs".[33]

Methane hydrates

Source: United States Geological Survey

An explanation for some of the disappearances has focused on the presence of large fields of methane hydrates (a form of natural gas) on the continental shelves.[34] Laboratory experiments carried out in Australia have proven that bubbles can, indeed, sink a scale model ship by decreasing the density of the water;[35][36][37] any wreckage consequently rising to the surface would be rapidly dispersed by the Gulf Stream. It has been hypothesized that periodic methane eruptions (sometimes called "mud volcanoes") may produce regions of frothy water that are no longer capable of providing adequate buoyancy for ships. If this were the case, such an area forming around a ship could cause it to sink very rapidly and without warning.

Publications by the USGS describe large stores of undersea hydrates worldwide, including the Blake Ridge area, off the coast of the southeastern United States.[38] However, according to the USGS, no large releases of gas hydrates are believed to have occurred in the Bermuda Triangle for the past 15,000 years.[3]

Notable incidents

USS Cyclops

The incident resulting in the single largest loss of life in the history of the US Navy not related to combat occurred when the collier Cyclops, carrying a full load of manganese ore and with one engine out of action, went missing without a trace with a crew of 309 sometime after March 4, 1918, after departing the island of Barbados. Although there is no strong evidence for any single theory, many independent theories exist, some blaming storms, some capsizing, and some suggesting that wartime enemy activity was to blame for the loss.[39][40] In addition, two of Cyclops's sister ships, Proteus and Nereus were subsequently lost in the North Atlantic during World War II. Both ships were transporting heavy loads of metallic ore similar to that which was loaded on Cyclops during her fatal voyage. In all three cases structural failure due to overloading with a much denser cargo than designed is considered the most likely cause of sinking.

Carroll A. Deering

A five-masted schooner built in 1919, Carroll A. Deering was found hard aground and abandoned at Diamond Shoals, near Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, on January 31, 1921. Rumors and more at the time indicated Deering was a victim of piracy, possibly connected with the illegal rum-running trade during Prohibition, and possibly involving another ship, Hewitt, which disappeared at roughly the same time. Just hours later, an unknown steamer sailed near the lightship along the track of Deering, and ignored all signals from the lightship. It is speculated that Hewitt may have been this mystery ship, and possibly involved in Deering's crew disappearance.[41]

Flight 19

%252C_on_1_September_1942_(80-G-427475).jpg.webp)

Flight 19 was a training flight of five TBM Avenger torpedo bombers that disappeared on December 5, 1945, while over the Atlantic. The squadron's flight plan was scheduled to take them due east from Fort Lauderdale for 141 mi (227 km), north for 73 mi (117 km), and then back over a final 140-mile (230-kilometre) leg to complete the exercise. The flight never returned to base. The disappearance was attributed by Navy investigators to navigational error leading to the aircraft running out of fuel.

One of the search and rescue aircraft deployed to look for them, a PBM Mariner with a 13-man crew, also disappeared. A tanker off the coast of Florida reported seeing an explosion[42] and observing a widespread oil slick when fruitlessly searching for survivors. The weather was becoming stormy by the end of the incident.[43] According to contemporaneous sources the Mariner had a history of explosions due to vapour leaks when heavily loaded with fuel, as it might have been for a potentially long search-and-rescue operation.

Star Tiger and Star Ariel

G-AHNP Star Tiger disappeared on January 30, 1948, on a flight from the Azores to Bermuda; G-AGRE Star Ariel disappeared on January 17, 1949, on a flight from Bermuda to Kingston, Jamaica. Both were Avro Tudor IV passenger aircraft operated by British South American Airways.[44] Both planes were operating at the very limits of their range and the slightest error or fault in the equipment could keep them from reaching the small island.[1]

Douglas DC-3

On December 28, 1948, a Douglas DC-3 aircraft, number NC16002, disappeared while on a flight from San Juan, Puerto Rico, to Miami. No trace of the aircraft, or the 32 people on board, was ever found. A Civil Aeronautics Board investigation found there was insufficient information available on which to determine probable cause of the disappearance.[45]

Connemara IV

A pleasure yacht was found adrift in the Atlantic south of Bermuda on September 26, 1955; it is usually stated in the stories (Berlitz, Winer)[13][14] that the crew vanished while the yacht survived being at sea during three hurricanes. The 1955 Atlantic hurricane season shows Hurricane Ione passing nearby between 14 and 18 September, with Bermuda being affected by winds of almost gale force.[1] In his second book on the Bermuda Triangle, Winer quoted from a letter he had received from Mr J.E. Challenor of Barbados:[46]

On the morning of September 22, Connemara IV was lying to a heavy mooring in the open roadstead of Carlisle Bay. Because of the approaching hurricane, the owner strengthened the mooring ropes and put out two additional anchors. There was little else he could do, as the exposed mooring was the only available anchorage. ... In Carlisle Bay, the sea in the wake of Hurricane Janet was awe-inspiring and dangerous. The owner of Connemara IV observed that she had disappeared. An investigation revealed that she had dragged her moorings and gone to sea.

KC-135 Stratotankers

On August 28, 1963, a pair of US Air Force KC-135 Stratotanker aircraft collided and crashed into the Atlantic 300 miles west of Bermuda.[47][48] Some writers[10][13][14] say that while the two aircraft did collide there were two distinct crash sites, separated by over 160 miles (260 km) of water. However, Kusche's research showed that the unclassified version of the Air Force investigation report revealed that the debris field defining the second "crash site" was examined by a search and rescue ship, and found to be a mass of seaweed and driftwood tangled in an old buoy.[1]

See also

References

Notes

- Kusche, 1975.

- "The Case of the Bermuda Triangle". NOVA / Horizon. 1976-06-27. PBS.

- "Bermuda Triangle". Gas Hydrates at the USGS. Woods Hole. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012.

- "E. V. W. Jones AP article". Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- E.V.W. Jones (September 16, 1950). "Same Big World, Sea's Puzzles Still Baffle Men In Pushbutton Age". Associated Press.

- "Has the 'Mystery' of the Bermuda Triangle Finally Been Solved?". 2016-10-24. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- George X. San (October 1952). "Sea Mystery at Our Back Door". Fate.

- Allen W. Eckert (April 1962). "The Mystery of The Lost Patrol". American Legion Magazine. Cited in James R. Lewis (editor), Satanism Today: An Encyclopedia of Religion, Folklore, and Popular Culture, page 72, segment by Jerome Clark (ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2001). ISBN 1-57607-292-4

- Diana Formisano Willett, Paranormal Fright, p. 9 (AuthorHouse, 2013), ISBN 978-1-4817-3268-0

- Gaddis, Vincent (1964), "The Deadly Bermuda Triangle", Argosy

- Vincent Gaddis (1965). Invisible Horizons.

- Spencer, 1969.

- Berlitz, 1974.

- Winer 1974

- "Strange fish: the scientifiction of Charles F. Berlitz, 1913–2003". Skeptic. Altadena, CA. March 2004.

- "Study finds shipwrecks threaten precious seas". BBC News/science. 7 June 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Bermuda Triangle doesn't make the cut on list of world's most dangerous oceans". The Christian Science Monitor. 2013-06-10. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "Equinox: The Bermuda Triangle". Archived from the original on 2009-05-27. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- "V A Fogg" (PDF). USCG. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- Taves, Ernest H. (1978). The Skeptical Inquirer. 111 (1): 75–76. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Singer, Barry (1979). The Humanist. XXXIX (3): 44–45. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Radford, Benjamin. "Lessons From A Middle School Bermuda Triangle Q&A". Center for Inquiry. Archived from the original on 21 November 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Shinn, Eugene A. (January 2004). "A Geologist's Adventures with Bimini Beachrock and Atlantis True Believers". Skeptical Inquirer. Amherst, New York: Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Archived from the original on April 6, 2007.

- "UFO over Bermuda Triangle". Ufos.about.com. June 29, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- Cochran-Smith, Marilyn (2003). "Bermuda Triangle: dichotomy, mythology, and amnesia". Journal of Teacher Education. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. 54 (4): 275. doi:10.1177/0022487103256793.

- "Bermuda Triangle". US Navy. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- "National Geomagnetism Program | Charts | North America | Declination" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- Phillips, Pamela. "The Gulf Stream". USNA/Johns Hopkins. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- Mayell, Hillary (15 December 2003). "Bermuda Triangle: Behind the Intrigue". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. National Geographic Partners, LLC. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Scott, Captain Thomas A. (1994). Histories & Mysteries: The Shipwrecks of Key Largo (1st ed.). Best Publishing Company. p. 124. ISBN 0941332330.

- "Downdraft likely sank clipper, The Miami News, May 23, 1986, p. 6A". Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- Kenny Walter (24 October 2016). "Bermuda Triangle Mystery Explained". RandD Magazine. Retrieved 2016-10-24. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - Gruy, H. J. (March 1998). "Office of Scientific & Technical Information, OSTI, U.S. Department of Energy, DOE". Petroleum Engineer International. OTSI. 71 (3). OSTI 616279.

- "Could methane bubbles sink ships?". Monash Univ.

- Jason Dowling (2003-10-23). "Bermuda Triangle mystery solved? It's a load of gas". The Age.

- Terrence Aym (2010-08-06). "How Brilliant Computer Scientists Solved the Bermuda Triangle Mystery". Salem-News.com.

- Paull, C.K.; W.P., D. (1981). "Appearance and distribution of the gas hydrate reflection in the Blake Ridge region, offshore southeastern United States". Gas Hydrates at the USGS. Woods Hole. MF-1252. Archived from the original on 2012-02-18.

- "Bermuda Triangle". D Merrill. Archived from the original on 2002-11-24.

- "Myths and Folklore of Bermuda". Bermuda Cruises. Archived from the original on 2009-06-10.

- "Carroll A Deering". Graveyard of the Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2005-08-28.

- "The Loss of Flight 19". history.navy.mil.

- "The Disappearance of Flight 19". Bermuda-Triangle.Org. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- "The Tudors". Bermuda-Triangle.Org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- "Airborne Transport, Miami, December 1948" (PDF). Aviation Safety. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-01-03. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- Winer 1975, pp. 95–96

- Accident description for 61-0322 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2 February 2013.

- Accident description for 61-0319 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2 February 2013.

Bibliography

The incidents cited above, apart from the official documentation, come from the following works. Some incidents mentioned as having taken place within the Triangle are found only in these sources:

- Berg, Daniel (2000). Bermuda Shipwrecks. East Rockaway, NY: Aqua Explorers. ISBN 0-9616167-4-1.

- Berlitz, Charles (1974). The Bermuda Triangle (1st ed.). Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04114-4.

- Group, David (1984). The Evidence for the Bermuda Triangle. Wellingborough, Northamptonshire: Aquarian Press. ISBN 0-85030-413-X.

- Jeffrey, Adi-Kent Thomas (1975). The Bermuda Triangle. ISBN 0-446-59961-1.

- Kusche, Lawrence David (1975). The Bermuda Triangle Mystery Solved. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books. ISBN 0-87975-971-2.

- Quasar, Gian J. (2003). Into the Bermuda Triangle: Pursuing the Truth Behind the World's Greatest Mystery. International Marine / Ragged Mountain Press. ISBN 0-07-142640-X. Reprinted in paperback in 2005; ISBN 0-07-145217-6.

- Spencer, John Wallace (1969). Limbo Of The Lost. ISBN 0-686-10658-X.

- Winer, Richard (1974). The Devil's Triangle. ISBN 0-553-10688-0.

- Winer, Richard (1975). The Devil's Triangle 2. ISBN 0-553-02464-7.

Further reading

- Newspaper articles

ProQuest has newspaper source material for many incidents, archived in Portable Document Format (PDF). The newspapers include The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Atlanta Constitution. To access this website, registration is required, usually through a library connected to a college or university.

Flight 19

- "Great Hunt On For 27 Navy Fliers Missing In Five Planes Off Florida", The New York Times, December 7, 1945.

- "Wide Hunt For 27 Men In Six Navy Planes", The Washington Post, December 7, 1945.

- "Fire Signals Seen In Area Of Lost Men", The Washington Post, December 9, 1945.

SS Cotopaxi

- "Lloyd's posts Cotopaxi As 'Missing'", The New York Times, January 7, 1926.

- "Efforts To Locate Missing Ship Fail", The Washington Post, December 6, 1925.

- "Lighthouse Keepers Seek Missing Ship", The Washington Post, December 7, 1925.

- "53 On Missing Craft Are Reported Saved", The Washington Post, December 13, 1925.

USS Cyclops (AC-4)

- "Cold High Winds Do $25,000 Damage", The Washington Post, March 11, 1918.

- "Collier Overdue A Month", The New York Times, April 15, 1918.

- "More Ships Hunt For Missing Cyclops", The New York Times, April 16, 1918.

- "Haven't Given Up Hope For Cyclops", The New York Times, April 17, 1918.

- "Collier Cyclops Is Lost; 293 Persons On Board; Enemy Blow Suspected", The Washington Post, April 15, 1918.

- "U.S. Consul Gottschalk Coming To Enter The War", The Washington Post, April 15, 1918.

- "Cyclops Skipper Teuton, 'Tis Said", The Washington Post, April 16, 1918.

- "Fate Of Ship Baffles", The Washington Post, April 16, 1918.

- "Steamer Met Gale On Cyclops' Course", The Washington Post, April 19, 1918.

Carroll A. Deering

- "Piracy Suspected In Disappearance Of 3 American Ships", The New York Times, June 21, 1921.

- "Bath Owners Skeptical", The New York Times, June 22, 1921. piera antonella

- "Deering Skipper's Wife Caused Investigation", The New York Times, June 22, 1921.

- "More Ships Added To Mystery List", The New York Times, June 22, 1921.

- "Hunt On For Pirates", The Washington Post, June 21, 1921

- "Comb Seas For Ships", The Washington Post, June 22, 1921.

- "Port Of Missing Ships Claims 3000 Yearly", The Washington Post, July 10, 1921.

Wreckers

- "'Wreckreation' Was The Name Of The Game That Flourished 100 Years Ago", The New York Times, March 30, 1969.

S.S. Suduffco

- "To Search For Missing Freighter", The New York Times, April 11, 1926.

- "Abandon Hope For Ship", The New York Times, April 28, 1926.

Star Tiger and Star Ariel

- "Hope Wanes in Sea Search For 28 Aboard Lost Airliner", The New York Times, January 31, 1948.

- "72 Planes Search Sea For Airliner", The New York Times, January 19, 1949.

DC-3 Airliner NC16002 disappearance

- "30-Passenger Airliner Disappears In Flight From San Juan To Miami", The New York Times, December 29, 1948.

- "Check Cuba Report Of Missing Airliner", The New York Times, December 30, 1948.

- "Airliner Hunt Extended", The New York Times, December 31, 1948.

Harvey Conover and Revonoc

- "Search Continuing For Conover Yawl", The New York Times, January 8, 1958.

- "Yacht Search Goes On", The New York Times, January 9, 1958.

- "Yacht Search Pressed", The New York Times, January 10, 1958.

- "Conover Search Called Off", The New York Times, January 15, 1958.

KC-135 Stratotankers

- "Second Area Of Debris Found In Hunt For Jets", The New York Times, August 31, 1963.

- "Hunt For Tanker Jets Halted", The New York Times, September 3, 1963.

- "Planes Debris Found In Jet Tanker Hunt", The Washington Post, August 30, 1963.

B-52 Bomber (Pogo 22)

- "U.S.-Canada Test Of Air Defence A Success", The New York Times, October 16, 1961.

- "Hunt For Lost B-52 Bomber Pushed In New Area", The New York Times, October 17, 1961.

- "Bomber Hunt Pressed", The New York Times, October 18, 1961.

- "Bomber Search Continuing", The New York Times, October 19, 1961.

- "Hunt For Bomber Ends", The New York Times, October 20, 1961.

Charter vessel Sno'Boy

- "Plane Hunting Boat Sights Body In Sea", The New York Times, July 7, 1963.

- "Search Abandoned For 40 On Vessel Lost In Caribbean", The New York Times, July 11, 1963.

- "Search Continues For Vessel With 55 Aboard In Caribbean", The Washington Post, July 6, 1963.

- "Body Found In Search For Fishing Boat", The Washington Post, July 7, 1963.

SS Marine Sulphur Queen

- "Tanker Lost In Atlantic; 39 Aboard", The Washington Post, February 9, 1963.

- "Debris Sighted In Plane Search For Tanker Missing Off Florida", The New York Times, February 11, 1963.

- "2.5 Million Is Asked In Sea Disaster", The Washington Post, February 19, 1963.

- "Vanishing Of Ship Ruled A Mystery", The New York Times, April 14, 1964.

- "Families Of 39 Lost At Sea Begin $20-Million Suit Here", The New York Times, June 4, 1969.

- "10-Year Rift Over Lost Ship Near End", The New York Times, February 4, 1973.

SS Sylvia L. Ossa

- "Ship And 37 Vanish In Bermuda Triangle On Voyage To U.S.", The New York Times, October 18, 1976.

- "Ship Missing In Bermuda Triangle Now Presumed To Be Lost At Sea", The New York Times, October 19, 1976.

- "Distress Signal Heard From American Sailor Missing For 17 Days", The New York Times, October 31, 1976.

- Website links

The following websites have either online material that supports the popular version of the Bermuda Triangle, or documents published from official sources as part of hearings or inquiries, such as those conducted by the United States Navy or United States Coast Guard. Copies of some inquiries are not online and may have to be ordered; for example, the losses of Flight 19 or USS Cyclops can be ordered direct from the United States Naval Historical Center.

- Text of Feb, 1964 Argosy Magazine article by Vincent Gaddis

- United States Coast Guard database of selected reports and inquiries

- U.S. Navy Historical Center Bermuda Triangle FAQ

- U.S. Navy Historical C/ The Bermuda Triangle: Startling New Secrets, Sci Fi Channel documentary (November 2005)

- Navy Historical Center: The Loss Of Flight 19

- on losses of heavy ships at sea

- Bermuda Shipwrecks

- Association of Underwater Explorers shipwreck listings page

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships

- "Summary of Missing Planes". Bermuda-Triangle.Org. Archived from the original on 3 June 2004. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- Books

Most of the works listed here are largely out of print. Copies may be obtained at your local library, or purchased used at bookstores, or through eBay or Amazon.com. These books are often the only source material for some of the incidents that have taken place within the Triangle.

- Into the Bermuda Triangle: Pursuing the Truth Behind the World's Greatest Mystery by Gian J. Quasar, International Marine/Ragged Mountain Press (2003) ISBN 0-07-142640-X; contains list of missing craft as researched in official records. (Reprinted in paperback (2005) ISBN 0-07-145217-6).

- The Bermuda Triangle, Charles Berlitz (ISBN 0-385-04114-4): Out of print.

- The Bermuda Triangle Mystery Solved (1975). Lawrence David Kusche (ISBN 0-87975-971-2)

- Limbo Of The Lost, John Wallace Spencer (ISBN 0-686-10658-X)

- The Evidence for the Bermuda Triangle (1984), David Group (ISBN 0-85030-413-X)

- The Final Flight (2006), Tony Blackman (ISBN 0-9553856-0-1). This book is a work of fiction.

- Bermuda Shipwrecks (2000), Daniel Berg(ISBN 0-9616167-4-1)

- The Devil's Triangle (1974), Richard Winer (ISBN 0-553-10688-0); this book sold well over a million copies by the end of its first year; to date there have been at least 17 printings.

- The Devil's Triangle 2 (1975), Richard Winer (ISBN 0-553-02464-7)

- From the Devil's Triangle to the Devil's Jaw (1977), Richard Winer (ISBN 0-553-10860-3)

- Ghost Ships: True Stories of Nautical Nightmares, Hauntings, and Disasters (2000), Richard Winer (ISBN 0-425-17548-0)

- The Bermuda Triangle (1975) by Adi-Kent Thomas Jeffrey (ISBN 0-446-59961-1)

- Bara, Mike (2019). The Triangle: The truth behind the world's most enduring mystery. Kempton, IL: Adventures Unlimited. p. 191. ASIN B07SVG79C5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bermuda Triangle. |

| Look up Bermuda Triangle in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "Database of selected reports and inquiries". United States Coast Guard.

- Quasar, Gian. "Bermuda Triangle Mystery". Bermuda-Triangle.Org. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012.

- Quasar, Gian. "Gian Quasar's Bermuda Triangle". – updated version of Quasar's Bermuda Triangle information.

- "Bermuda Triangle FAQ". US Navy Historical Center.

- "Selective Bibliography". US Navy Historical Center. Archived from the original on 2006-07-09.

- "The Loss Of Flight 19". US Navy Historical Center.

- "On losses of heavy ships at sea".

- "Bermuda Shipwrecks".

- Barnette, Michael C. "Shipwreck listings page". Association of Underwater Explorers.

- SigmaDocumentaries. "The Mystery of the Bermuda Triangle". Sigma Documentaries.

- Dunning, Brian (20 November 2012). "Skeptoid #337: The Bermuda Triangle and the Devil's Sea". Skeptoid. Retrieved 15 June 2017.