Paul is dead

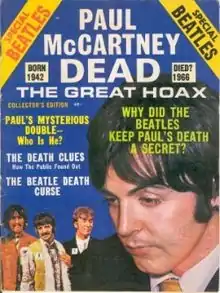

"Paul is dead" is an urban legend and conspiracy theory alleging that English musician Paul McCartney, of the Beatles, died on 9 November 1966 and was secretly replaced by a look-alike. The rumour began circulating around 1967, but grew in popularity after being reported on American college campuses in late 1969. Proponents based the theory on perceived clues found in Beatles songs and album covers. Clue-hunting proved infectious, and within a few weeks had become an international phenomenon.

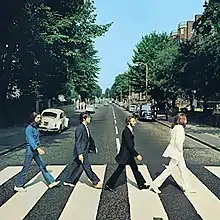

According to the theory, McCartney died in a car crash and to spare the public from grief, the surviving Beatles replaced him with the winner of a McCartney look-alike contest, sometimes identified as "William Campbell" or "Billy Shears". Afterwards, the band left messages in their music and album artwork to communicate the truth to their fans. These include the 1968 song "Glass Onion", in which Lennon sings "here's another clue for you all / the walrus was Paul", and the cover photo of their album Abbey Road, in which McCartney is shown barefoot and walking out of step with his bandmates.

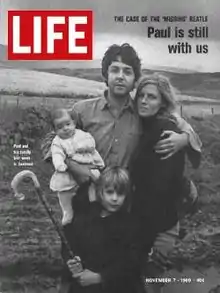

Rumours declined after an interview with McCartney, who had been secluded with his family in Scotland, was published in Life magazine in November 1969. During the 1970s, the phenomenon was the subject of analysis in the fields of sociology, psychology and communications. McCartney parodied the hoax with the title and cover art of his 1993 live album, Paul Is Live. In 2009, Time magazine included "Paul is dead" in its feature on ten of "the world's most enduring conspiracy theories".

Beginnings

In early 1967, a rumour circulated in London that Paul McCartney had been killed in a traffic accident while driving along the M1 motorway on 7 January.[1] The rumour was acknowledged and rebutted in the February issue of The Beatles Book, a fanzine.[1][2] McCartney then alluded to the rumour during a press conference held around the release of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club in May.[3] By 1967, the Beatles were known for sometimes including backmasking in their music.[4] Analysing their lyrics for hidden meaning had also become a popular trend in the US.[5] In November 1968, their self-titled double LP (also known as the "White Album") was released containing the track "Glass Onion". John Lennon wrote the song in response to "gobbledygook" said about Sgt. Pepper. In a later interview, he said that he was purposely confusing listeners with lines such as "the Walrus was Paul" – a reference to his song "I Am the Walrus" from the 1967 EP and album Magical Mystery Tour.[6]

On 17 September 1969, Tim Harper, an editor of the Drake Times-Delphic, the student newspaper of Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, published an article titled "Is Beatle Paul McCartney Dead?" The article addressed a rumour being circulated on campus that cited clues from recent Beatles albums, including a message interpreted as "Turn me on, dead man", heard when the White Album track "Revolution 9" is played backwards. Also referenced was the back cover of Sgt. Pepper, where every Beatle except McCartney is photographed facing the viewer, and the front cover of Magical Mystery Tour, which depicts one unidentified band member in a differently coloured suit from the other three.[7] According to music journalist Merrell Noden, Harper's Drake Times-Delphic was the first to publish an article on the "Paul is dead" theory.[8][nb 1] Harper later said that it had become the subject of discussion among students at the start of the new academic year, and he added: "A lot of us, because of Vietnam and the so-called Establishment, were ready, willing and able to believe just about any sort of conspiracy."[8]

In late September 1969, the Beatles released the album Abbey Road as they were in the process of disbanding.[10] On 10 October, the Beatles' press officer, Derek Taylor, responded to the rumour stating: "Recently we've been getting a flood of inquiries asking about reports that Paul is dead. We've been getting questions like that for years, of course, but in the past few weeks we've been getting them at the office and home night and day. I'm even getting telephone calls from disc jockeys and others in the United States."[11][12] Throughout this period, McCartney felt isolated from his bandmates in his opposition to their choice of business manager, Allen Klein, and distraught at Lennon's private announcement that he was leaving the group.[13][14] With the birth of his daughter Mary in late August, McCartney had withdrawn to focus on his family life.[15] On 22 October, the day that the "Paul is dead" rumour became an international news story,[16] McCartney, his wife Linda and their two daughters travelled to Scotland to spend time at his farm near Campbeltown.[17]

Growth

On 12 October 1969, a caller to Detroit radio station WKNR-FM told disc jockey Russ Gibb about the rumour and its clues.[8] Gibb and other callers then discussed the rumour on air for the next hour,[18] during which Gibb offered further potential clues.[19] Two days later, The Michigan Daily published a satirical review of Abbey Road by University of Michigan student Fred LaBour, who had listened to the exchange on Gibb's show,[8] under the headline "McCartney Dead; New Evidence Brought to Light".[20][21] It identified various clues to McCartney's death on Beatles album covers, particularly on the Abbey Road sleeve. LaBour later said he had invented many of the clues and was astonished when the story was picked up by newspapers across the United States.[22] Noden writes that "Very soon, every college campus, every radio station, had a resident expert."[8] WKNR fuelled the rumour further with its two-hour programme The Beatle Plot, which first aired on 19 October.

The story was soon taken up by more mainstream radio stations in the New York area, WMCA and WABC.[23] In the early hours of 21 October, WABC disc jockey Roby Yonge discussed the rumour on-air for over an hour before being pulled off the air for breaking format. At that time of night, WABC's signal covered a wide listening area and could be heard in 38 US states and, at times, in other countries.[24] Although the Beatles' press office denied the rumour, McCartney's atypical withdrawal from public life contributed to its escalation.[25] Vin Scelsa, a student broadcaster in 1969, later said that the escalation was indicative of the countercultural influence of Bob Dylan, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, since: "Every song from them – starting about late 1966 – became a personal message, worthy of endless scrutiny ... they were guidelines on how to live your life."[8]

WMCA dispatched Alex Bennett to the Beatles' Apple Corps headquarters in London on 23 October,[26] further to his extended coverage of the "Paul is dead" theory.[23][27] There, Ringo Starr told Bennett: "If people are gonna believe it, they're gonna believe it. I can only say it's not true."[26] In a radio interview with John Small of WKNR, Lennon said that the rumour was "insane" but good publicity for Abbey Road.[28][nb 2] On Halloween night 1969, WKBW in Buffalo, New York broadcast a program titled Paul McCartney Is Alive and Well – Maybe, which analysed Beatles lyrics and other clues. The WKBW DJs concluded that the "Paul is dead" hoax was fabricated by Lennon.[30]

Before the end of October 1969, several record releases had exploited the phenomenon of McCartney's alleged demise.[23] These included "The Ballad of Paul" by the Mystery Tour;[31] "Brother Paul" by Billy Shears and the All Americans; "So Long Paul" by Werbley Finster, a pseudonym for José Feliciano;[32] and Zacharias and His Tree People's "We're All Paul Bearers (Parts One and Two)".[33] Another song was Terry Knight's "Saint Paul",[23] which had been a minor hit in June that year and was subsequently adopted by radio stations as a tribute to "the late Paul McCartney".[34][nb 3] According to a report in Billboard magazine in early November, Shelby Singleton Productions planned to issue a documentary LP of radio segments discussing the phenomenon.[36] In Canada, Polydor Records exploited the rumour in their artwork for Very Together, a repackaging of the Beatles' pre-fame recordings with Tony Sheridan, using a cover that showed four candles, one of which had just been snuffed out.[37]

Premise

Proponents of the theory maintained that, on 9 November 1966, McCartney had an argument with his bandmates during a Beatles recording session and drove off angrily in his car, crashed, and was decapitated.[23][38] To spare the public from grief, or simply as a joke, the surviving Beatles replaced him with the winner of a McCartney look-alike contest.[23] This scenario was facilitated by the Beatles' recent retirement from live performance and by their choosing to present themselves with a new image for their next album, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[39]

In LaBour's telling, the stand-in was an "orphan from Edinburgh named William Campbell" whom the Beatles then trained to impersonate McCartney.[8] Others contended that the man's name was William Shears Campbell, later abbreviated to Billy Shears,[40] and the replacement was instigated by Britain's MI5 out of concern for the severe distress McCartney's death would cause the Beatles' audience.[41] In this latter telling, the surviving Beatles were said to be wracked by guilt at their duplicity, and therefore left messages in their music and album artwork to communicate the truth to their fans.[41][42]

Dozens of supposed clues to McCartney's death have been identified by fans and followers of the legend. These include messages perceived when listening to songs being played backwards and symbolic interpretations of both lyrics and album cover imagery.[43][44] One frequently cited example is the suggestion that the words "I buried Paul" are spoken by Lennon in the final section of the song "Strawberry Fields Forever", which the Beatles recorded in November and December 1966. Lennon later said that the words were actually "Cranberry sauce".[45][46]

Another example is the interpretation of the Abbey Road album cover as depicting a funeral procession. Lennon, dressed in white, is said to symbolise the heavenly figure; Starr, dressed in black, symbolises the undertaker; George Harrison, in denim, represents the gravedigger; and McCartney, barefoot and out of step with the others, symbolises the corpse.[20] The number plate of the white Volkswagen Beetle in the photo – containing the characters LMW 28IF – was identified as further "evidence".[8][47] "28IF" represented McCartney's age "if" he had still been alive (although McCartney was 27 when the album was recorded and released)[25] while "LMW" stood for "Linda McCartney weeps" or "Linda McCartney, widow".[48][nb 4] That the left-handed McCartney held a cigarette in his right hand was also said to support the idea that he was an impostor.[23]

Rebuttal

On 21 October 1969, the Beatles' press office again issued statements denying the rumour, deeming it "a load of old rubbish"[49] and saying that "the story has been circulating for about two years – we get letters from all sorts of nuts but Paul is still very much with us".[50] On 24 October, BBC Radio reporter Chris Drake was granted an interview with McCartney at his farm.[17] McCartney said that the speculation was understandable, given that he normally did "an interview a week" to ensure he remained in the news.[51] Part of the interview was first broadcast on Radio 4, on 26 October,[52] and subsequently on WMCA in the US.[51] According to author John Winn, McCartney had conceded to the interview "in hopes that people hearing his voice would see the light", but the ploy failed.[51][nb 5]

McCartney was secretly filmed by a CBS News crew as he worked on his farm. As in his and Linda's segment in the Beatles' promotional clip for "Something", which the couple filmed privately around this time, McCartney was unshaven and unusually scruffy-looking in his appearance.[53] His next visitors were a reporter and photographer from Life magazine. Irate at the intrusion, he swore at the pair, threw a bucket of water over them and was captured on film attempting to hit the photographer. Fearing that the photos would damage his image, McCartney then approached the pair and agreed to pose for a photo with his family and answer the reporter's questions, in exchange for the roll of film containing the offending pictures.[54] In Winn's description, the family portrait used for Life's cover shows McCartney no longer "shabbily attired", but "clean-shaven and casually but smartly dressed".[53]

Following the publication of the article and the photo, in the issue dated 7 November,[53] the rumour started to decline.[8] In the interview, McCartney was quoted as saying:

Perhaps the rumour started because I haven't been much in the press lately. I have done enough press for a lifetime, and I don't have anything to say these days. I am happy to be with my family and I will work when I work. I was switched on for ten years and I never switched off. Now I am switching off whenever I can. I would rather be a little less famous these days.[55]

Aftermath

In November 1969, Capitol Records sales managers reported a significant increase in sales of Beatles catalogue albums, attributed to the rumour.[56] Rocco Catena, Capitol's vice-president of national merchandising, estimated that "this is going to be the biggest month in history in terms of Beatles sales".[23][56] The rumour benefited the commercial performance of Abbey Road in the US, where it comfortably outsold all of the band's previous albums.[57] Sgt. Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour, both of which had been off the charts since February, re-entered the Billboard Top LPs chart,[23] peaking at number 101 and number 109, respectively.[58]

A television special dedicated to "Paul is dead" was broadcast on WOR in New York on 30 November.[22] Titled Paul McCartney: The Complete Story, Told for the First and Last Time, it was set in a courtroom and hosted by celebrity lawyer F. Lee Bailey,[32] who cross-examined LaBour,[22] Gibb and other proponents of the theory, and heard opposing views from "witnesses" such as McCartney's friend Peter Asher and Allen Klein.[23] Bailey left it to the viewer to determine a conclusion.[23] Before the recording, LaBour told Bailey that his article had been intended as a joke, to which Bailey sighed and replied, "Well, we have an hour of television to do; you're going to have to go along with this."[22]

– Paul McCartney

McCartney returned to London in December. Bolstered by Linda's support, he began recording his debut solo album at his home in St John's Wood.[59] Titled McCartney, and recorded without his bandmates' knowledge,[60][61] it was "one of the best-kept secrets in rock history" until shortly before its release in April 1970, according to author Nicholas Schaffner, and led to the announcement of the Beatles' break-up.[62] In his 1971 song "How Do You Sleep?", in which he attacked McCartney's character,[63] Lennon described the theorists as "freaks" who "were right when they said you was dead".[64] The rumour was also cited in the hoax surrounding the Canadian band Klaatu,[65] after a January 1977 review of their debut album 3:47 EST sparked rumours that the group were in fact the Beatles.[66] In one telling, this theory contended that the album had been recorded in late 1966 but then mislaid until 1975, at which point Lennon, Harrison and Starr elected to issue it in McCartney's memory.[65]

LaBour later became notable as the bassist for the western swing group Riders in the Sky, which he co-founded in 1977. In 2008, he joked that his success as a musician had extended his fifteen minutes of fame for his part in the rumour to "seventeen minutes".[67] In 2015, he told The Detroit News that he is still periodically contacted by conspiracy theorists who have attempted to present him with supposed new developments on the McCartney rumours.[68]

Analysis and legacy

Author Peter Doggett writes that, while the theory behind "Paul is dead" defied logic, its popularity was understandable in a climate where citizens were faced with conspiracy theories insisting that the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 was in fact a coup d'état.[69] Schaffner said that, given its origins as an item of gossip and intrigue generated by a select group in the "Beatles cult", "Paul is dead" serves as "a genuine folk tale of the mass communications era".[9] He also described it as "the most monumental hoax since Orson Welles' War of the Worlds broadcast persuaded thousands of panicky New Jerseyites that Martian invaders were in the vicinity".[9] In his book Revolution in the Head, Ian MacDonald says that the Beatles were partly responsible for the phenomenon due to their incorporation of "random lyrics and effects", particularly in the White Album track "Glass Onion" in which Lennon invited clue-hunting by including references to other Beatles songs.[4] MacDonald groups it with the "psychic epidemics" that were encouraged by the rock audience's use of hallucinogenic drugs and which escalated with Charles Manson's homicidal interpretation of the White Album and Mark David Chapman's religion-motivated murder of Lennon in 1980.[70]

During the 1970s, the phenomenon became a subject of academic study in America in the fields of sociology, psychology and communications.[71] Among sociological studies, Barbara Suczek recognised it as, in Schaffner's description, a contemporary reading of the "archetypal myth wherein the beautiful youth dies and is resurrected as a god".[9] Psychologists Ralph Rosnow and Gary Fine attributed its popularity partly to the shared, vicarious experience of searching for clues without consequence for the participants. They also said that for a generation distrustful of the media following the Warren Commission's report, it was able to thrive amid a climate informed by "The credibility gap of Lyndon Johnson's presidency, the widely circulated rumors after the Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy assassinations, as well as attacks on the leading media sources by the yippies and Spiro Agnew".[9] American social critic Camille Paglia locates the "Paul is dead" phenomenon to the Ancient Greek tradition symbolised by Adonis and Antinous, as represented in the cult of rock music's "pretty, long-haired boys who mesmerize both sexes", and she adds: "It's no coincidence that it was Paul McCartney, the 'cutest' and most girlish of the Beatles, who inspired a false rumor that swept the world in 1969 that he was dead."[72]

"Paul is dead" has continued to inspire analysis into the 21st century, with published studies by Andru J. Reeve, Nick Kollerstrom and Brian Moriarty, among others, and exploitative works in the mediums of mockumentary and documentary film.[41] Writing in 2016, Beatles biographer Steve Turner said, "the theory still has the power to flare back into life."[40] He cited a 2009 Wired Italia magazine article that featured an analysis by two forensic research consultants who compared selected photographs of McCartney taken before and after his alleged death by measuring features of the skull.[40] According to the scientists' findings, the man shown in the post-November 1966 images was not the same.[40][73][nb 6]

Similar rumours concerning other celebrities have been circulated, including the unsubstantiated allegation that Canadian singer Avril Lavigne died in 2003 and was replaced by a person named Melissa Vandella.[74][75] In an article on the latter phenomenon, The Guardian described the 1969 McCartney hoax as "Possibly the best known example" of a celebrity being the focus of "a (completely unverified) cloning conspiracy theory".[74] In 2009, Time magazine included "Paul is dead" in its feature on ten of "the world's most enduring conspiracy theories".[42]

In popular culture

There have been many references to the legend in popular culture, including the following examples.

- In the Rutles' 1978 television film satirising the Beatles' history, All You Need Is Cash, the identity of the alleged dead band member was transferred to the George Harrison character, Stig O'Hara, who was supposed to have died "in a flash fire at a water bed shop" and been replaced by a Madame Tussauds wax model. Building on Harrison's reputation as the "Quiet Beatle", the "Stig is dead" theory was supported by his lack of dialogue in the film[76] and clues such as his trouser-less appearance on the cover of the Rutles' Shabby Road album.[77]

- McCartney titled his 1993 live album Paul Is Live in reference to the hoax.[78] He also presented it in a sleeve that parodied the Abbey Road cover and its clues.[79]

- The 1995 video for "Free as a Bird" – a song recorded by Lennon in the late 1970s and completed by McCartney, Harrison and Starr for the band's Anthology project – references "Paul is dead", among other myths relating to the Beatles' impact during the 1960s. According to author Gary Burns, the video indulges in the same "semiological excess" as the 1969 hoax and thereby "spoof[s]" obsessive clue-hunting.[80]

- In 2010, American author Alan Goldsher published the mashup novel Paul Is Undead: The British Zombie Invasion, which depicts all of the Beatles as zombies except Ringo Starr.[81]

- In 2015, the indie rock band EL VY released a song called "Paul Is Alive", which contains lyrics referencing Beatlemania[82] and partly addresses the 1969 rumour.[83]

- A 2018 comedy short film, Paul Is Dead, depicts a version of events where McCartney dies during a musical retreat and is replaced by a look-alike named Billy Shears.[84]

Notes

- Writing in 1977, author Nicholas Schaffner said the theory has been traced to a student thesis at Ohio Wesleyan University and to a prank article published in the student newspaper for Illinois University.[9]

- Estranged from McCartney, Lennon said: "Paul McCartney couldn't die without the world knowing it. The same as he couldn't get married ... [or] go on holiday without the world knowing it. It's just insanity – but it's a great plug for Abbey Road."[29]

- A Capitol Records recording artist, Knight had been present during the White Album session when Starr temporarily left the band,[34] in August 1968.[35] In the song, the singer conveys his fears that the Beatles were about to disband.[34]

- The fact that he would have been 27 in late 1969, rather than 28, was dismissed with the rationale that, in the Hindu tradition, infants were one year old at birth.[8]

- In the 2000 book The Beatles Anthology, McCartney says that his reaction to the rumour's growth had been: "Well, we'd better play it for all it's worth. It's publicity, isn't it?"[29]

- In his article on the legacy of "Paul is dead", for Dawn in January 2017, Anis Shivani wrote that the narrative has grown, in the manner of JFK's assassination, to incorporate related conspiracy theories. In this expanded narrative, Lennon's murder in 1980, Harrison's near-fatal stabbing in 1999, and the death of Beatles associate Mal Evans in 1976 are all credited to forces protecting the "truth" behind "Paul is dead".[41]

References

- Yoakum, Jim (May–June 2000). "The Man Who Killed Paul McCartney". Gadfly Online. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Beatle News". The Beatles Book. February 1967.

- Moriarty, Brian (1999). "Who Buried Paul?". ludix.com. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- MacDonald 1998, pp. 16, 273–75.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 115.

- The Beatles 2000, p. 306.

- Schmidt, Bart (18 September 2009). "It Was 40 Years Ago, Yesterday ..." Drake University: Cowles Library blog. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- Noden, Merrell (2003). "Dead Man Walking". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days of Revolution (The Beatles' Final Years – Jan 1, 1968 to Sept 27, 1970). London: Emap. p. 114.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 128.

- Miles 2001, pp. 353, 354.

- "Paul McCartney Asserts He's 'Alive and Well'". Courier-Post. Camden, New Jersey. 10 October 1969.

- "Beatle Paul McCartney Is Really Alive". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 11 October 1969. p. 5.

- Sounes 2010, pp. 261, 263–64.

- Rodriguez 2010, pp. 1, 396, 398.

- Miles 1997, p. 559.

- Winn 2009, p. 332.

- Miles 2001, p. 358.

- Morris, Julie (23 October 1969). "The Beatle Paul Mystery – As Big as Rock Music Itself". Detroit Free Press. p. 6.

- Winn 2009, p. 241.

- LaBour, Fred (14 October 1969). "McCartney Dead; New Evidence Brought to Light". The Michigan Daily. p. 2.

- Gould 2007, pp. 593–94.

- Glenn, Allen (11 November 2009). "Paul Is Dead (Said Fred)". Michigan Today. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 127.

- "Why Did WABC Have Such a Great Signal?". Musicradio 77 WABC. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- Sounes 2010, p. 262.

- Winn 2009, p. 333.

- McKinney 2003, p. 291.

- Winn 2009, pp. 332–33.

- The Beatles 2000, p. 342.

- Bisci, John. "WKBW: Paul McCartney Is Alive And Well – Maybe, 1969". ReelRadio. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 281.

- McKinney 2003, p. 292.

- Clayson 2003, p. 118.

- "Terry Knight Speaks". Blogcritics. 2 March 2004. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011.

- MacDonald 1998, p. 271.

- Billboard staff (8 November 1969). "McCartney 'Death' Gets 'Disk Coverage' Dearth". Billboard. p. 3.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 130.

- Hoffmann & Bailey 1990, pp. 165–66.

- Gould 2007, p. 593.

- Turner 2016, p. 368.

- Shivani, Anis (15 January 2017). "Paul is Dead: The Conspiracy Theory That Won't Go Away". Dawn. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- Time staff (July 2009). "Separating Fact from Fiction: Paul Is Dead". Time. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- Patterson 1998, pp. 193–97.

- Clayson 2003, pp. 117–18.

- MacDonald 1998, p. 273fn.

- Yorke, Ritchie (7 February 1970). "A Private Talk With John". Rolling Stone. p. 22.

- The Beatles 2000, pp. 341, 342.

- Draper 2008, p. 76.

- "Beatle Spokesman Calls Rumor of McCartney's Death 'Rubbish'". The New York Times. 22 October 1969. p. 8.

- Phillips, B.J. (22 October 1969). "McCartney 'Death' Rumors". The Washington Post. p. B1.

- Winn 2009, p. 334.

- Miles 2001, p. 359.

- Winn 2009, p. 335.

- Sounes 2010, pp. 262–63.

- Neary, John (7 November 1969). "The Magical McCartney Mystery". Life. pp. 103–06.

- Burks, John (29 November 1969). "A Pile of Money on Paul's 'Death'". Rolling Stone. pp. 6, 10.

- Schaffner 1978, pp. 126–27.

- Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 361.

- Sounes 2010, p. 264.

- Doggett 2011, pp. 111, 121.

- Rodriguez 2010, p. 2.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 135.

- Rodriguez 2010, p. 399.

- Sounes 2010, p. 290.

- Raymond, Adam K. (23 October 2016). "The 70 Greatest Conspiracy Theories in Pop-Culture History". Vulture. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Schaffner 1978, pp. 189–90.

- LaBour, Fred (1 August 2008). "True Westerners: Fred Labour – Too Slim of Riders in the Sky". True West Magazine. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- Rubin, Neal (10 September 2015). "Paul McCartney still isn't dead. Neither is the story". The Detroit News. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- Doggett 2011, p. 107.

- MacDonald 1998, pp. 273–75.

- Schaffner 1978, pp. 128–29.

- Paglia, Camille (Winter 2003). "Cults and Cosmic Consciousness: Religious Vision in the American 1960s". Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics. 3rd. 10 (3): 61–62.

- Carlesi, Gabriella et al. (2009) "Chiedi chi era quel «Beatle»", Wired Italia

- Cresci, Elena (16 May 2017). "Why fans think Avril Lavigne died and was replaced by a clone named Melissa". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- Estatie, Lamia (15 May 2017). "The Avril Lavigne conspiracy theory returns". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- Rodriguez 2010, p. 308.

- Idle, Eric (1978). "The Rutles Story". The Rutles (LP booklet). Warner Bros. Records. p. 16.

- Clayson 2003, p. 228.

- Doggett 2011, p. 339.

- Burns 2000, pp. 180–81.

- Flood, Alison (31 July 2009). "The Beatles flesh out zombie mash-up craze". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- Van Nguyen, Dean (7 October 2015). "EL VY post lyric video for new single 'Paul Is Alive'". NME. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- WCYT staff (16 November 2015). "EL VY – 'Return to the Moon'". wcyt.org. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- "Paul Is Dead ... A Comedy Short Film Inspired by the Classic Bizarre Rock & Roll Conspiracy Theory". urbanistamagazine.uk. 30 September 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

Sources

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8.

- Burns, Gary (2000). "Refab Four: Beatles for Sale in the Age of Music Video". In Inglis, Ian (ed.). The Beatles, Popular Music and Society: A Thousand Voices. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-22236-9.

- Castleman, Harry; Podrazik, Walter J. (1976). All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25680-8.

- Clayson, Alan (2003). Paul McCartney. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 1-86074-482-6.

- Doggett, Peter (2011). You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup. New York, NY: It Books. ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8.

- Draper, Jason (2008). A Brief History of Album Covers. London: Flame Tree Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84786-211-2.

- Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America. London: Piatkus. ISBN 978-0-7499-2988-6.

- Hoffmann, Frank W.; Bailey, William G. (1990). Arts & Entertainment Fads. Binghamton, NY: The Haworth Press. ISBN 0-86656-881-6.

- MacDonald, Ian (1998). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6697-8.

- McKinney, Devin (2003). Magic Circles: The Beatles in Dream and History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01202-X.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now. New York, NY: Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-5248-0.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- Patterson, R. Gary (1998). The Walrus Was Paul: The Great Beatle Death Clues. New York, NY: Fireside. ISBN 0-684-85062-1.

- Reeve, Andru J. (1994). Turn Me On, Dead Man: The Beatles and the "Paul-Is-Dead" Hoax. Ann Arbor, MI: Popular Culture, Ink. ISBN 978-1418482947.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2010). Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Sounes, Howard (2010). Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-723705-0.

- Turner, Steve (2016). Beatles '66: The Revolutionary Year. New York, NY: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-247558-9.

- Winn, John C. (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.