Common tsessebe

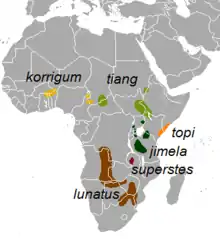

The common tsessebe or sassaby (Damaliscus lunatus lunatus) is one of six subspecies of African antelope Damaliscus lunatus of the genus Damaliscus and subfamily Alcelaphinae in the family Bovidae. It is most closely related to the topi, korrigum, coastal topi and tiang (all subspecies of Damaliscus lunatus), and the bangweulu tsessebe and bontebok in the same genus. Tsessebe are found primarily in Angola, Zambia, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Eswatini (Swaziland), and South Africa.[2][3][4] Tsessebe are one of the fastest antelopes in Africa[5] and can run at speeds up to 90 km/h.[6]

| Common tsessebe | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Tsessebe in Botswana | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | D. lunatus |

| Subspecies: | D. l. lunatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Damaliscus lunatus (Burchell, 1824) | |

| Trinomial name | |

| Damaliscus lunatus lunatus (Burchell, 1824) | |

| |

| Subspecies of Damaliscus lunatus | |

Description

_close-up_(11684009833).jpg.webp)

Adult tsessebe are 150 to 230 cm in length.[7] They are quite large animals, with males weighing 137 kg and females weighing 120 kg, on average.[8] Their horns range from 37 cm for females to 40 cm for males. For males, horn size plays an important role in territory defense and mate attraction, although horn size is not positively correlated with territorial factors of mate selection.[8] Their bodies are chestnut brown. The fronts of their faces and their tail tufts are black; the forelimbs and thigh are greyish or bluish-black. Their hindlimbs are brownish-yellow to yellow and their bellies are white.[9] In the wild, tsessebe usually live a maximum of 15 years, but in some areas, their average lifespan is drastically decreased due to overhunting and the destruction of habitat.[9]

Behavior

Tsessebe are social animals. Females form herds composed of six to 10, with their young. After males turn one year of age, they are ejected from the herd and form bachelor herds that can be as large as 30 young bulls. Territorial adult bulls form herds the same size as young bulls, although the formation of adult bull herds is mainly seen in the formation of a lek.[10] Tsessebe declare their territory through a variety of behaviors. Territorial behavior includes moving in an erect posture, high-stepping, defecating in a crouch stance, ground-horning, mud packing, shoulder-wiping, and grunting.

The most important aggressive display of territorial dominance is in the horning of the ground. Another far more curious form of territory marking is through the anointing of their foreheads and horns with secretions from glands near their eyes. Tsessebe accomplish this by inserting grass stems into their preorbital glands to coat them with secretion, then waving it around, letting the secretions fall onto their heads and horns. This process is not as commonly seen as ground-horning, nor is its purpose as well known.[11]

Several of their behaviors strike scientists as peculiar. One such behavior is the habit of sleeping tsessebe to rest their mouths on the ground with their horns sticking straight up into the air. Male tsessebe has also been observed standing in parallel ranks with their eyes closed, bobbing their heads back and forth. These habits are peculiar because scientists have yet to find a proper explanation for their purposes or functions.[11]

Diet and habitat

Tsessebe are primarily grazing herbivores[12] in grasslands, open plains, and lightly wooded savannas, but they are also found in rolling uplands and very rarely in flat plains below 1500 m above sea level.[11] Tsessebe found in the Serengeti usually feed in the morning between 8:00 and 9:00 am and in the afternoon after 4:00 pm. The periods before and after feeding are spent resting and digesting or watering during dry seasons. Tsessebe can travel up to 5 km to reach a viable water source. To avoid encounters with territorial males or females, tsessebe usually travel along territorial borders, though it leaves them open to attacks by lions and leopards.[11]

Breeding and reproduction

Tsessebe reproduce at a rate of one calf per year per mating couple.[7] Calves reach sexual maturity in two to three and half years. After mating, the gestation period of a tsessebe cow lasts seven months. The rut, or period when males start competing for females, starts in mid-February and stretches through March.[10] The female estrous cycle is shorter, but happens in this time.

_(11683592113).jpg.webp)

The breeding process starts with the development of a lek. Leks are established by the congregation of adult males in an area that females visit only for mating. Lekking is of particular interest since the female choice of a mate in the lek area is independent of any direct male influence. Several options are available to explain how females choose a mate, but the most interesting is in the way the male's group in the middle of a lek.

The grouping of males can appeal to females for several reasons. First, groups of males can protect from predators. Secondly, if males group in an area with a low food supply, it prevents competition between males and females for resources. Finally, the grouping of males provides females with a wider variety of mates to choose from, as they are all located in one central area.[13] Dominant males occupy the center of the leks, so females are more likely to mate at the center than at the periphery of the lek.[12]

A study by Bro-Jorgensen (2003) allowed a closer look into lek dynamics. The closer a male is to the center of the lek, the greater his mating success rate. For a male to reach the center of the lek, he must be strong enough to outcompete other males. Once a male's territory is established in the middle of the lek, it is maintained for quite a while; even if an area opens up at the center, males rarely move to fill it unless they can outcompete the large males already present. However, maintaining central lek territory has many physical drawbacks. For example, males are often wounded in the process of defending their territory from hyenas and other males.[14]

Conservation status

The population of Damaliscus lunatus was estimated to be in the tens of thousands in 1998, so it was declared at low risk of extinction. However, the IUCN Species Survival Commission observed a general population decline that would result in the population becoming vulnerable to extinction by the year 2025.[2] Tsessebe populations once were present in much greater numbers, but populations declined due to habitat destruction, with bush encroachment playing a primary role.[4]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Damaliscus lunatus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Damaliscus lunatus. |

- IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). "Damaliscus lunatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2009. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern .

- East, Rod; IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group (1998). "African Antelope Database". Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission. 21: 200–207.

- Damaliscus lunatus, MSW3

- Dorgeloh, Werner G. (2006). "Habitat Suitability for tsessebe Damaliscus lunatus lunatus". African Journal of Ecology. 44 (3): 329–336. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00654.x.

- "Tsessebe | Botswana Wildlife Guide". www.botswana.co.za. Retrieved 2017-10-28.

- Van den Berg, Ingrid (2015). Kruger self-drive. Van den Berg, Philip, Van den Berg, Heinrich. Cascades, South Africa: HPH Publishing. p. 102. ISBN 9780994675125. OCLC 934195661.

- Kingdon, J (2015-04-23). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 428–431. ISBN 9781472921352.

- Bro-Jorgensen, J (2007). "The Intensity of Sexual Selection Predicts Weapon Size in Male Bovids". Evolution. 61 (6): 1316–1326. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00111.x. PMID 17542842. S2CID 24278541.

- Haltenorth, T (1980). The Collins Field Guide to the Mammals of African Including Madagascar. New York, NY: The Stephen Greene Press, Inc. pp. 81–82.

- Anonymous. "Tsessebe". Kruger National Park. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- Estes, R.D. (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. pp. 142–146. ISBN 9780520080850.

- Bro-Jorgensen, J (2003). "The Significance of Hotspots to Lekking Topi Antelopes (Damaliscus lunatus)" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 53 (5): 324–331. doi:10.1007/s00265-002-0573-0. S2CID 52829538. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-12. Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- Bateson, Patrick (1985). Mate Choice. New York, NY: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. pp. 109–112. ISBN 978-0-521-27207-0.

- Bro-Jorgensen, Jakob; Sarah M Durant (2003). "Mating Strategies of Topi Bulls: Getting in the centre of attention". Animal Behaviour. 65 (3): 585–594. doi:10.1006/anbe.2003.2077. S2CID 54229602.

Damaliscus lunatus, The Ultimate Ungulate Factsheet