Mountain gazelle

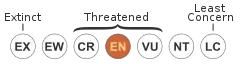

The mountain gazelle or the Palestine mountain gazelle[3][4] (Gazella gazella) is a species of gazelle widely but unevenly distributed.[5]

| Mountain gazelle[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mountain gazelle (male) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Antilopinae |

| Genus: | Gazella |

| Species: | G. gazella |

| Binomial name | |

| Gazella gazella (Pallas, 1766) | |

Physical description

Mountain gazelles are one of the few mammals in which both sexes have horns. Males have significantly larger horns with rings around them. Females will also have horns, but they will be thinner and shorter. Along with the horns, mountain gazelles are sexually dimorphic, meaning that males are larger than females. A wild male can range from 17-29.5 kg, while females are 16–25 kg in weight.[6] Mountain gazelles can reach running speeds up to 80 km/h (50 mph).[7]

Population and range

Mountain gazelles are most abundant in Israel, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights, but are also found in parts of Jordan and Turkey. While there are not accurate estimates of the number of individuals in the wild, Israel estimated there to be only 3,100 endangered gazelles in their country.[8] Less than 3,000 mountain gazelles are left within their natural range.

Habitat

Gazelles have adapted to live in dry, desert-like conditions.[9] They spend most of their time at the top of mountains and hills. Living in an annual average temperature of 21-23 °C, gazelles prefer to bed on the tops of the hills/mountains to avoid the heat during the day. Around dawn and dusk, these mammals will be found traversing the hills to eat in light forests, fields, or desert plateaus.[6] It is less well adapted to hot, dry conditions than the Dorcas gazelle, which appears to have replaced the mountain gazelle through some of its range during the late Holocene in a period of climatic warming.

Ecology

The mountain gazelle is a diurnal species, they are awake during the day and sleep at night. They are also very territorial and with their herds, but typically stay in herds of three to eight individuals. There are three main groups in the mountain gazelle community: maternity herds, bachelor male herds, or territorial solitary males.[6]

Survival and reproduction

In the wild, mountain gazelles rarely survive past the age of eight but can live up to 15 years in captivity when taken care of. By 12 months, a female gazelle can begin breeding.[10] For males, 18 months is when they will start breeding.[6] Being polygamous,[10] not spending their lives with one other individual, mountain gazelles' typical breeding season is during the early winter months. Females will give birth to one offspring per year mostly between the months of April and May.[6] A few days prior to giving birth the mother will leave her herd and live in solitary. For up to two months, the mother and her offspring will stay by themselves while the mother watches out for predators. Common predators include foxes, jackals, and wolves that will try to attack the fawn.[11] While young males will stay with their mother for only six months before departing to a herd of young males, young females will sometimes join their mother with a herd.[6]

Food

Its range coincides closely with that of the acacia trees that grow in these areas. It is mainly a grazing species, though this varies with food availability. They can survive for long periods of time without a water source. Instead, they acquire freshwater from succulents and dew droplets from plants.[6]

History

In 1985, a large population of mountain gazelles built up through game conservation in two Israeli reserves, in the southern Golan Heights and Ramat Yissachar, was decimated by foot and mouth disease. To prevent such occurrences, a plan was drawn up to stabilize the female population at 1,000 in the Golan and 700 in Ramat Yissachar.[12]

Threats and conservation

Mountain gazelles were hunted throughout Israel because they were thought of as a pest until 1993. Their numbers are still low for multiple reasons. In some areas, they face predation from feral dogs and jackals. They also face poachers for their skin, meat, and horns. As with other animals, mountain gazelles are harmed by road accidents, habitat degradation, and habitat fragmentation. Mountain gazelles are now a legally protected species, but often there is not enough enforcement to protect the species. Although the range of the gazelle was once extensive, Israel is now the only country where the gazelle is now extant, but even in Israel the future is grim without more conservation efforts. In 1985, the gazelle population was approximately 10,000, and in 2016 the population has declined to 2,500.[9][13][14]

Subspecies

The Hatay mountain gazelle lives on the northern Syrian border and a population has been discovered in the Hatay Province of Turkey.[15]

Historically, some others such as the Cuvier's gazelle (G. cuvieri) were included as a subspecies,[16] but recent authorities consistently treat them as separate species.[17]

References

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Gazella gazella". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 637–722. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2017). "Gazella gazella". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T8989A50186574. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T8989A50186574.en.

- Castelló, AvJosé (2016). Bovids of the World: Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princeton University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1400880652. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- Mallon, David; Kingswood, Steven (2001). Antelopes: North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. IUCN. p. 8 & 100. ISBN 2831705940. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- "The story of gazelles in Jerusalem and what I want for them… – Kaitholil.com". Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- Lee, Kari. "Gazella gazella mountain gazelle". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Lee, K. "Gazella gazella". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- "Gazella gazella (Ha'tsviha'Israeli, Idmi, Mountain Gazelle)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- "Gazelle gazelle". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- Baharav, Dan (January 1974). "NOTES ON THE POPULATION STRUCTURE AND BIOMASS OF THE MOUNTAIN GAZELLE, GAZELLA GAZELLA GAZELLA". Israel Journal of Zoology. 23 (1): 39–44. doi:10.1080/00212210.1974.10688395 (inactive 2021-01-17).CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- "Mountain gazelle (Gazella gazella)". Wildscreen Arkive. Archived from the original on 2018-05-01. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- Mountain gazelle management in northern Israel in relation to wildlife disease control. (PDF) . oie.int.

- Adam, Rachelle (2016). "Finding Safe Passage through a Wave of Extinctions: Israel's Endangered Mountain Gazelle". Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy. 19 (2): 136–158. doi:10.1080/13880292.2016.1167472. S2CID 87840827.

- Hadas, L.; Hermon, D.; Bar-Gal, G. K. (2016). "Before they are gone - improving gazelle protection using wildlife forensic genetics". Forensic Science International. Genetics. 24: 51–54. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2016.05.018. PMID 27294679.

- "250 endangered Mountain gazelles found in Turkey – First record in Turkey". Wildlife Extra. Archived from the original on 2012-09-19. Retrieved 2014-01-15.

- ADW: Gazella gazella: INFORMATION. Animaldiversity.org. Retrieved on 2015-09-25.

- Mallon, D.P. & Cuzin, F. (2008). "Gazella cuvieri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gazella gazella. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Gazella gazella. |