European bison

The European bison (Bison bonasus) or the European wood bison, also known as the wisent[lower-alpha 1] (/ˈviːzənt/ or /ˈwiːzənt/), or the zubr[lower-alpha 2] (/zuːbər/), is a European species of bison. It is one of two extant species of bison, alongside the American bison. The European bison is the heaviest wild land animal in Europe and individuals in the historical past may have been even larger than modern animals. During Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, bison became extinct in much of Europe and Asia, surviving into the 20th century only in northern-central Europe and the northern Caucasus Mountains. During the early years of the 20th century bison were hunted to extinction in the wild. The species, now numbering several thousand head and returned to the wild by captive breeding programmes, is no longer in immediate danger of extinction, but remains absent from most of its historical range. It is not to be confused with the aurochs (Bos primigenius), the extinct ancestor of domestic cattle, with which it co-existed into historical times.

| European bison | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| A male bison in the process of moulting | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Bovinae |

| Genus: | Bison |

| Species: | B. bonasus |

| Binomial name | |

| Bison bonasus | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Bos bonasus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Besides humans, bison have few predators. In the 19th century, there were scattered reports of wolves, bears, Asiatic lions, and Caspian tigers hunting bison. In the past, especially during the Middle Ages, bison were commonly killed for their hide and meat, and to produce drinking horns. European bison were hunted to extinction in the wild in the early 20th century, with the last wild animals of the B. b. bonasus subspecies being shot in the Białowieża Forest (on the Belarus–Poland border) in 1921, and the last of the Caucasian wisent subspecies (B. b. caucasicus) in the north-western Caucasus in 1927.[2] The Carpathian wisent (B. b. hungarorum) had been hunted to extinction in the mid-1800s. The Białowieża or lowland European bison was kept alive in captivity, and has since been reintroduced into several countries in Europe. In 1996, the International Union for Conservation of Nature classified the European bison as an endangered species, no longer extinct in the wild. Its status has improved since then, changing to vulnerable and later to near threatened.

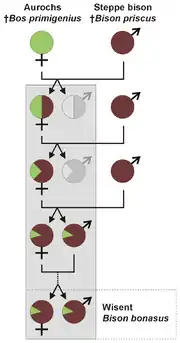

European bison were first scientifically described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. Some later descriptions treat the European bison as conspecific with the American bison. Three subspecies of European bison existed in the recent past, but only one, the nominate subspecies (B. b. bonasus), survives today. Analysis of mitochondrial genomes and nuclear DNA revealed that the wisent is theoretically the descendant of a species which arose as a result of hybridisation between the extinct steppe bison (Bison priscus) and the ancestors of the aurochs (Bos primigenius), since their genetic material contains up to 10% aurochs DNA sequences; the possible hybrid, now extinct, is referred to informally as the Higgs bison, a pun in reference to the Higgs boson.[3] Alternatively, the Pleistocene woodland bison has been suggested as the ancestor to the species.[4][5]

The European bison is one of the national animals of Poland and Belarus.[6][7]

Etymology

The ancient Greeks and ancient Romans were the first to name bison as such; the 2nd-century AD authors Pausanias and Oppian referred to them as Hellenistic Greek: βίσων, romanized: bisōn.[8] Earlier, in the 4th century BC, during the Hellenistic period, Aristotle referred to bison as βόνασος, bónasos.[8] He also noted that the Paeonians called it μόναπος (monapos).[9] Claudius Aelianus, writing in the late 2nd or early 3rd centuries AD, also referred to the species as βόνασος, and both Pliny the Elder's Natural History and Gaius Julius Solinus used Latin: bĭson and bonāsus.[8] Both Martial and Seneca the Younger mention bison (pl. bisontes).[8] Later Latin spellings of the term included visontes, vesontes, and bissontes.[8]

John Trevisa is the earliest author cited by the Oxford English Dictionary as using, in his 1398 translation of Bartholomeus Anglicus's De proprietatibus rerum, the Latin plural bisontes in English, as "bysontes" (Middle English: byſontes and bysountes).[8] Philemon Holland's 1601 translation of Pliny's Natural History, referred to "bisontes". The marginalia of the King James Version gives "bison" as a gloss for the Biblical animal called the "pygarg" mentioned in the Book of Deuteronomy.[8] Randle Cotgrave's 1611 French–English dictionary notes that French: bison was already in use, and it may have influenced the word's adoption into English, which may alternatively be directly borrowed from Latin.[8] John Minsheu's 1617 lexicon, Ductor in linguas, gives a definition for Bíson (Early Modern English: "a wilde oxe, great eied, broad-faced, that will neuer be tamed").[8]

In the 18th century, the name of the European animal was applied to the closely related American bison (initially in Latin in 1693, by John Ray) and the Indian bison (the gaur, Bos gaurus).[8] Historically, the word was also applied to Indian domestic cattle, the zebu (B. indicus or B. primigenius indicus).[8] Because of the scarcity of the European bison, the word "bison" was most familiar in relation to the American species.[8]

By the time of the adoption of "bison" into Early Modern English, the early medieval English name for the species had long been obsolete: the Old English: wesend had descended from Proto-Germanic: *wisand, *wisund and was related to Old Norse: vísundr.[8] The word "wisent" was then borrowed in the 19th century from modern German: Wisent [ˈviːzɛnt], itself related to Old High German: wisunt, wisent, wisint, and to Middle High German: wisant, wisent, wisen, and ultimately, like the Old English name, from Proto-Germanic.[10] The Proto-Germanic root: *wis-, also found in weasel, originally referred to the animal's musk.

The word "zubr" in English is a borrowing from Polish: żubr [ʐubr], previously also used to denote one race of the European bison.[11][12] The Polish żubr is similar to the word for the European bison in other modern Slavic languages, such as Upper Sorbian: žubr or Russian: зубр. The noun for the European bison in all living Slavonic tongues is thought to be derived from Proto-Slavic: *zǫbrъ ~ *izǫbrъ, which itself possibly comes from Proto-Indo-European: *ǵómbʰ- for tooth, horn, or peg.[13]

Description

.jpg.webp)

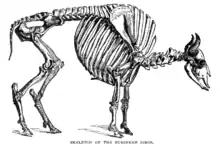

The European bison is the heaviest surviving wild land animal in Europe. Similar to their American cousins, European bisons were potentially larger historically than remnant descendants;[14] modern animals are about 2.8 to 3.3 m (9.2 to 10.8 ft) in length, not counting a tail of 30 to 92 cm (12 to 36 in), 1.8 to 2.1 m (5.9 to 6.9 ft) in height, and 615 to 920 kg (1,356 to 2,028 lb) in weight for males, and about 2.4 to 2.9 m (7.9 to 9.5 ft) in body length without tails, 1.69 to 1.97 m (5.5 to 6.5 ft) in height, and 424 to 633 kg (935 to 1,396 lb) in weight for females.[14] At birth, calves are quite small, weighing between 15 and 35 kg (33 and 77 lb). In the free-ranging population of the Białowieża Forest of Belarus and Poland, body masses among adults (aged 6 and over) are 634 kg (1,398 lb) on average in the cases of males, and 424 kg (935 lb) among females.[15][16] An occasional big bull European bison can weigh up to 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) or more[17][18][19] with old bull records of 1,900 kg (4,200 lb) for lowland wisent and 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) for Caucasian wisent.[14]

On average, it is lighter in body mass, and yet slightly taller at the shoulder, than its American relatives, the wood bison (Bison bison athabascae) and the plains bison (Bison bison bison).[20] Compared to the American species, the wisent has shorter hair on the neck, head, and forequarters, but longer tail and horns. See differences from American bison.

The European bison makes a variety of vocalisations depending on its mood and behaviour, but when anxious, it emits a growl-like sound, known in Polish as chruczenie ([xrutʂɛɲɛ]). This sound can also be heard from wisent males during the mating season.[21]

History

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

Historically, the lowland European bison's range encompassed most of the lowlands of northern Europe, extending from the Massif Central to the Volga River and the Caucasus. It may have once lived in the Asiatic part of what is now the Russian Federation. The European bison is known in southern Sweden only between 9500 and 8700 BP, and in Denmark similarly is documented only from the Pre-Boreal.[23] It is not recorded from the British Isles, nor from Italy or the Iberian Peninsula,[24] although prehistorical absence of the species among British Isles is debatable, based on fossils found on Doggerland or Brown Bank, and Isle of Wight and Oxfordshire, followed by fossil records of steppe bison from the isles.[25][26][27][28] A possible ancestor, the extinct steppe bison, B. priscus, is known from across Eurasia and North America, last occurring 7,000 BC[29] to 5,400 BC,[30] and is depicted in the Cave of Altamira and Lascaux. Another possible ancestor, the Pleistocene woodland bison (B. schoetensacki), was last present 36,000 BC.[4] Cave paintings appear to distinguish between B. bonasus and B. priscus.[31]

Within mainland Europe, its range decreased as human populations expanded and cut down forests. They seemed to be common in Aristotle's period on Mount Mesapion (possibly the modern Ograzhden).[9] In the same wider area Pausanias calling them Paeonian bulls and bisons, gives details on how they were captured alive; adding also the fact that a golden Paeonian bull head was offered to Delphi by the Paeonian king Dropion (3rd century BC) who lived in what is today Tikveš.[32] The last references (Oppian, Claudius Aelianus) to the animal in the transitional Mediterranean/Continental biogeographical region in the Balkans in the area of modern borderline between Greece, North Macedonia and Bulgaria date to the 3rd century AD.[33][34] In northern Bulgaria, the wisent survived until the 9th or 10th century AD.[35] There is a possibility that the species' range extended to East Thrace during the 7th – 8th century AD.[36] Its population in Gaul was extinct in the 8th century AD. The species survived in the Ardennes and the Vosges Mountains until the 15th century.[37] In the Early Middle Ages, the wisent apparently still occurred in the forest steppes east of the Urals, in the Altai Mountains, and seems to have reached Lake Baikal in the east. The northern boundary in the Holocene was probably around 60°N in Finland.[38]

European bison survived in a few natural forests in Europe, but their numbers dwindled. In the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, European bison in the Białowieża Forest were legally the property of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania until the third partition of Poland. Wild European bison herds also existed in the forest until the mid-17th century. Polish kings took measures to protect the bison. King Sigismund II Augustus instituted the death penalty for poaching a European bison in Białowieża in the mid-16th century. In the early 19th century, after the partitions of the Polish Commonwealth the Russian tsars retained old Lithuanian laws protecting the European bison herd in Białowieża. Despite these measures and others, the European bison population continued to decline over the following century, with only Białowieża and Northern Caucasus populations surviving into the 20th century.[39][40] The last European bison in Transylvania died in 1790.[41]

During World War I, occupying German troops killed 600 of the European bison in the Białowieża Forest for sport, meat, hides and horns.[39] A German scientist informed army officers that the European bison were facing imminent extinction, but at the very end of the war, retreating German soldiers shot all but nine animals.[39][40] The last wild European bison in Poland was killed in 1921. The last wild European bison in the world was killed by poachers in 1927 in the western Caucasus. By that year, fewer than 50 remained, all held by zoos.

The International Society for the Preservation of the Wisent was founded on 25 and 26 August 1923 in Berlin. Numerous experts joined the company, among themHermann Pohle, Max Hilzheimer and Julius Riemer. The aim of the society was to cooperate internationally to preserve the "Wisent, which was directly threatened with extinction. The last free-living wisent in the Caucasus was shot in 1927. The first goal of the society was to record all the still living bison, on the basis of which one could begin with a conservation breeding. The company, the first chairman of which was the director of the Frankfurt Zoo, Kurt Priemel, was joined by several private individuals and institutions, such as the American Bison Society, following the example of which the International Society for the Conservation of the Wisent was founded. Important members were, however, the Polish Hunting Association and the Poznań zoological gardens, as well as a number of Polish private individuals. They were also the first to provide substantial funds to acquire the first bison cows and bulls. The breeding book was published in the company's annual report from 1932. While Priemel aimed at a slow increase in the Wisent population with the pure conservation of the breeding line, Lutz Heck planned to suddenly increase the Wisent population by crossing American bison in 1934 in a separate breeding project in Munich. In it he was personally supported by the then Reichsjägermeister Hermann Göring, who hoped for huntable big game.[42] Lutz Heck promised his powerful supporter in writing: "Since surplus bulls will soon be set, the hunting of the Wisent will be possible again in the foreseeable future." Hermann Göring himself took over the patronage of the "German Professional Association of Wisent Breeders and Hegers", founded at the suggestion of Lutz Heck. Kurt Priemel, who had since resigned as president of the "International Society for the Preservation of the Wisent", warned in vain against a "manification". This criticism led Lutz Heck to threaten Priemel by announcing that Göring would take action against Priemel if he continued to oppose his crossing plans. Priemel was then banned from publishing in relation to bison breeding, and the regular bookkeeper of the "International Society", Erna Mohr, was also forced to hand over the official register in 1937.Thus, the older society was effectively incorporated into the newly created "professional community" and thus connected to the same. After the Second World War, therefore, only the pure-blooded bison in the game park Springe near Hanover were recognized as part of the international herd book.[43][44]

The first two bisons were released into nature to the Białowieża Forest in 1952.[45] By 1964 more than 100 existed.[46]

Genetic history

A 2003 study of mitochondrial DNA indicated four distinct maternal lineages in the tribe Bovini:

Y chromosome analysis associated wisent and American bison.[47] An earlier study, using amplified fragment-length polymorphism fingerprinting, showed a close association of wisent and American bison and probably with yak. It noted the interbreeding of Bovini species made determining relationships problematic.[48]

European bison can crossbreed with American bison. This hybrid is known in Poland as a żubrobizon. The products of a German interbreeding programme were destroyed after the Second World War. This programme was related to the impulse which created the Heck cattle. The cross-bred individuals created at other zoos were eliminated from breed books by the 1950s. A Russian back-breeding programme resulted in a wild herd of hybrid animals, which presently lives in the Caucasian Biosphere Reserve (550 animals in 1999).

Wisent-cattle hybrids also occur, similarly to the North American beefalo. Cattle and European bison hybridise fairly readily, but the calves cannot be born naturally (birth is not triggered correctly by the first-cross hybrid calf, so they must be delivered by Caesarian section). First-generation males are infertile. In 1847, a herd of wisent-cattle hybrids named żubroń (/ˈʒuːbrɒnj/) was created by Leopold Walicki. The animals were intended to become durable and cheap alternatives to cattle. The experiment was continued by researchers from the Polish Academy of Sciences until the late 1980s. Although the program resulted in a quite successful animal that was both hardy and could be bred in marginal grazing lands, it was eventually discontinued. Currently, the only surviving żubroń herd consists of just a few animals in Białowieża Forest, Poland and Belarus.

In 2016, the first whole genome sequencing data from two European bison bulls from the Białowieża Forest revealed that the bison and bovine species diverged from about 1.7 to 0.85 Mya, through a speciation process involving limited gene flow.[49] These data further support the occurrence of more recent secondary contacts, posterior to the divergence between Bos primigenius primigenius and B. p. namadicus (ca. 150,000 years ago), between the wisent and (European) taurine cattle lineages. An independent study of mitochondrial DNA and autosomal markers confirmed these secondary contacts (with an estimate of up to 10% of bovine ancestry in the modern wisent genome) leading the authors to go further in their conclusions by proposing the wisent to be a hybrid between steppe bison and aurochs with a hybridisation event originating before 120,000 years ago.[22] This is also consistent with the apparent Bos origin of the mitochondrial DNA.

Some of the authors however support the hypothesis that similarity of wisent and cattle (Bos) mitochondrial genomes is result of incomplete lineage sorting during divergence of Bos and Bison from their common ancestors rather than further post-speciation gene flow (ancient hybridisation between Bos and Bison). But they agree that limited gene flow from Bos primigenius taurus could account for the affiliation between wisent and cattle nuclear genomes (in contrast to mitochondrial ones).[50]

Alternatively, genome sequencing completed on the Pleistocene woodland bison (B. schoetensacki), and published in 2017, posit that genetic similarities between the Pleistocene woodland bison and the wisent suggest that B. schoetensaki was the ancestor of the European wisent.[4][5]

Behaviour and biology

Social structure and territorial behaviours

The European bison is a herd animal, which lives in both mixed and solely male groups. Mixed groups consist of adult females, calves, young aged 2–3 years, and young adult bulls. The average herd size is dependent on environmental factors, though on average, they number eight to 13 animals per herd. Herds consisting solely of bulls are smaller than mixed ones, containing two individuals on average. European bison herds are not family units. Different herds frequently interact, combine, and quickly split after exchanging individuals.[37]

Bison social structure has been described by specialists as a matriarchy, as it is the cows of the herd that lead it, and decide where the entire group moves to graze.[51] Although larger and heavier than the females, the oldest and most powerful male bulls are usually satellites that hang around the edges of the herd to protect the group.[52] Bulls begin to serve a more active role in the herd when a danger to the group's safety appears, as well as during the mating season – when they compete with each other.[53]

Territory held by bulls is correlated by age, with young bulls aged between five and six tending to form larger home ranges than older males. The European bison does not defend territory, and herd ranges tend to greatly overlap. Core areas of territory are usually sited near meadows and water sources.[37]

Reproduction

The rutting season occurs from August through to October. Bulls aged 4–6 years, though sexually mature, are prevented from mating by older bulls. Cows usually have a gestation period of 264 days, and typically give birth to one calf at a time.[37]

On average, male calves weigh 27.6 kg (60.8 lb) at birth, and females 24.4 kg (53.8 lb). Body size in males increases proportionately to the age of 6 years. While females have a higher increase in body mass in their first year, their growth rate is comparatively slower than that of males by the age of 3–5. Bulls reach sexual maturity at the age of two, while cows do so in their third year.[37]

European bison have lived as long as 30 years in captivity,[54] but in the wild their lifespans are shorter. The lifespan of a zubr in the wild is usually between 18 and 24 years, though females live longer than males.[55] Productive breeding years are between four and 20 years of age in females, and only between six and 12 years of age in males.

Diet

European bison feed predominantly on grasses, although they also browse on shoots and leaves; in summer, an adult male can consume 32 kg of food in a day.[56] European bison in the Białowieża Forest in Poland have traditionally been fed hay in the winter for centuries, and large herds may gather around this diet supplement.[56] European bison need to drink every day, and in winter can be seen breaking ice with their heavy hooves.[57] Despite their usual slow movements, European bison are surprisingly agile and can clear 3-m-wide streams or 2-m-high fences from a standing start.[57][58]

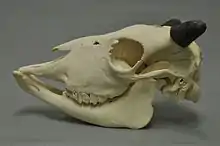

Differences from American bison

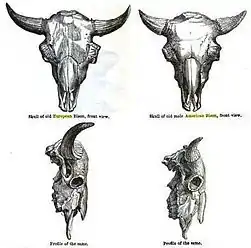

Although superficially similar, a number of physical and behavioural differences are seen between the European bison and the American bison. The zubr has 14 pairs of ribs, while the American bison has 15.[59] Adult European bison are (on average) taller than American bison, and have longer legs.[60] European bison tend to browse more, and graze less than their American relatives, due to their necks being set differently. Compared to the American bison, the nose of the European bison is set further forward than the forehead when the neck is in a neutral position.

The body of the wisent is less hairy, though its tail is hairier than that of the American species. The horns of the European bison point forward through the plane of their faces, making them more adept at fighting through the interlocking of horns in the same manner as domestic cattle, unlike the American bison, which favours charging.[61] European bison are less tameable than the American ones, and breed with domestic cattle less readily.[62]

In terms of behavioural capability, European bison runs slower and with less stamina yet jumps higher and longer than American bisons, showing signs of more developed adaptations into mountainous habitats.[14]

Conservation

The protection of the European bison has a long history; between the 15th and 18th centuries, those in the Forest of Białowieża were protected and their diet supplemented.[63] Efforts to restore this species to the wild began in 1929, with the establishment of the Bison Restitution Centre at Białowieża, Poland.[64][65] Subsequently, in 1948, the Bison Breeding Centre was established within the Prioksko-Terrasny Biosphere Reserve.

The modern herds are managed as two separate lines – one consisting of only Bison bonasus bonasus (all descended from only seven animals) and one consisting of all 12 ancestors, including the one B. b. caucasicus bull.[66] The latter is generally not considered a separate subspecies because they contain DNA from both B. b. bonasus and B. b. caucasicius, although some scientists classify them as a new subspecies, B. b. montanus.[67] Only a limited amount of inbreeding depression from the population bottleneck has been found, having a small effect on skeletal growth in cows and a small rise in calf mortality. Genetic variability continues to shrink. From five initial bulls, all current European bison bulls have one of only two remaining Y chromosomes.

Reintroduction

.jpg.webp)

Beginning in 1951, European bison have been reintroduced into the wild, including some areas where they were never found wild.[68] Free-ranging herds are currently found in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Romania, Russia, Slovakia,[69] Latvia, Switzerland, Kyrgyzstan, Germany,[70][71] and in forest preserves in the Western Caucasus. The Białowieża Primeval Forest, an ancient woodland that straddles the border between Poland and Belarus, continues to have the largest free-living zubr population in the world with around 1000 wild bison counted in 2014.[72] Herds have also been introduced in Moldova (2005),[73] Spain (2010),[74] Denmark (2012),[75] and the Czech Republic (2014).[76] The Wilder Blean project, headed up by the Wildwood Trust and Kent Wildlife Trust, is introducing European bison to the UK for the first time in 6000 years.[77] The herd of 3 females and 1 male will be set free in 2022 within a 2,500-acre conservation area in Blean Woods near Canterbury.[78][79]

Numbers by country

The total worldwide population recorded in 2019 was around 7,500 – about half of this number being in Poland and Belarus, with over 25% of the global population based in Poland alone.[7] For 2016, the number was 6,573 (including 4,472 free-ranging) and has been increasing.[80] Some local populations are estimated as:

Austria: 10 animals[81]

Austria: 10 animals[81] Belarus: 1962 animals[82] in 2019.

Belarus: 1962 animals[82] in 2019. Bulgaria: Around 150 animals in northeastern Bulgaria;[83] a smaller population has been reintroduced in the eastern Rhodope Mountains.[84]

Bulgaria: Around 150 animals in northeastern Bulgaria;[83] a smaller population has been reintroduced in the eastern Rhodope Mountains.[84] Czech Republic: 106 animals in 2017.[80]

Czech Republic: 106 animals in 2017.[80] Denmark: Two herds were established in the summer of 2012, as part of conservation of the species. First, 14 animals were released near the town of Randers, and later, seven animals on Bornholm. In June 2012, one male and six females were moved from Poland to the Danish island Bornholm. The plan was to examine if it is possible to establish a wild population of bison on the island over a five-year period. In 2018 it was decided to keep the bison on Bornholm, but fenced. The hope is that these animals will aid biodiversity by naturally maintaining open grassland and creating open gaps in the forest.[85] The bison have become a great attraction with more than 100,000 visitors every year.

Denmark: Two herds were established in the summer of 2012, as part of conservation of the species. First, 14 animals were released near the town of Randers, and later, seven animals on Bornholm. In June 2012, one male and six females were moved from Poland to the Danish island Bornholm. The plan was to examine if it is possible to establish a wild population of bison on the island over a five-year period. In 2018 it was decided to keep the bison on Bornholm, but fenced. The hope is that these animals will aid biodiversity by naturally maintaining open grassland and creating open gaps in the forest.[85] The bison have become a great attraction with more than 100,000 visitors every year. France: One herd was established in 2005 in the Alps near the village of Thorenc (close to the city of Grasse), as part of conservation of the species. In 2015, it contained around 50 animals.

France: One herd was established in 2005 in the Alps near the village of Thorenc (close to the city of Grasse), as part of conservation of the species. In 2015, it contained around 50 animals. Germany: A herd of eight wisents was released into nature in April 2013 at the Rothaarsteig natural reserve near Bad Berleburg (North Rhine-Westphalia). As of May 2015, 13 free-roaming wisents lived there. In September 2017 one of the free-living Polish animals swam the border river Oder and migrated to Germany. It was the first wild bison seen in Germany for more than 250 years. German authorities ordered the animal to be killed and it was shot dead by hunters on September 2017.[86][87]

Germany: A herd of eight wisents was released into nature in April 2013 at the Rothaarsteig natural reserve near Bad Berleburg (North Rhine-Westphalia). As of May 2015, 13 free-roaming wisents lived there. In September 2017 one of the free-living Polish animals swam the border river Oder and migrated to Germany. It was the first wild bison seen in Germany for more than 250 years. German authorities ordered the animal to be killed and it was shot dead by hunters on September 2017.[86][87] Hungary: 11 animals in the Őrség National Park[88] and few more in the Körös-Maros National Park.[89]

Hungary: 11 animals in the Őrség National Park[88] and few more in the Körös-Maros National Park.[89] Lithuania: 214 free-ranging animals as of 2017.[90]

Lithuania: 214 free-ranging animals as of 2017.[90] Moldova: Extirpated from Moldova since the 18th century, wisents were reintroduced with the arrival of three European bison from Białowieża Forest in Poland several days before Moldova's Independence Day on 27 August 2005.[91] Moldova is currently interested in expanding their wisent population, and began talks with Belarus in 2019 regarding a bison exchange program between the two countries.[92]

Moldova: Extirpated from Moldova since the 18th century, wisents were reintroduced with the arrival of three European bison from Białowieża Forest in Poland several days before Moldova's Independence Day on 27 August 2005.[91] Moldova is currently interested in expanding their wisent population, and began talks with Belarus in 2019 regarding a bison exchange program between the two countries.[92] Netherlands: Kraansvlak herd established in 2007 with three wisents, and expanded to six in 2008;[93] the Maashorst herd established in 2016 with 11 wisents;[94] and the Veluwe herd established in 2016 with a small herd.[95] In 2020 a new herd of 14 bison was established in the Slikken van de Heen. Numbers at the end of 2017 were: Kraansvlak 22, Maashorst 15 and the Veluwe 5, for a total of 42 animals.

Netherlands: Kraansvlak herd established in 2007 with three wisents, and expanded to six in 2008;[93] the Maashorst herd established in 2016 with 11 wisents;[94] and the Veluwe herd established in 2016 with a small herd.[95] In 2020 a new herd of 14 bison was established in the Slikken van de Heen. Numbers at the end of 2017 were: Kraansvlak 22, Maashorst 15 and the Veluwe 5, for a total of 42 animals. Poland: As of 31 December 2019 the number was 2269[96] – total population has been increasing by around 15% to 18% yearly.[7] Between 2017 and 1995, the number of zubrs in Poland doubled; from 2012 to 2017 it rose by 30%.[97] The data for 31 December 2017 showed 1873 animals living in Poland of which 1635 are in free-range herds.[98] The data for 31 December 2016 showed 1698 zubrs living in Poland of which 1455 were in free-range herds.[99] As of 2014 they were 1434 wisents, out of which 1212 were in free-range herds, and 522 belonged to the wild population in the Białowieża Forest. Compared to 2013, the total population in 2014 increased by 4.1%, while the free-ranging population increased by 6.5%.[80] Bison from Poland have also been transported beyond the country's borders to boost the local populations of other countries, among them Bulgaria, Spain, Romania, Czechia, and others.[100] Poland has been described as the world's breeding centre of the European bison.[21] As of 31 December 2019 data - out of 2269 zubrs, 2048 were free-roaming and 221 were living in captivity, including zoos.A total of 770 belonged to the wild population in the Białowieża Forest and 668 to Bieszczady National Park. As the numbers of animals is growing, more zubrs are spotted in areas where they have not been seen in centuries, especially migrating males in Spring. According to National Forests programme the next place where about 40 free-roaming zubrs will be placed is the Lublin Region (Lasy Janowskie) in 2020 and 2021. This new location announcement resulted in effecting ecologists' efforts to redesign some bridges of the S19 highway (which will be constructed in years 2020 - 2022 to allow large animals to cross it).[101]

Poland: As of 31 December 2019 the number was 2269[96] – total population has been increasing by around 15% to 18% yearly.[7] Between 2017 and 1995, the number of zubrs in Poland doubled; from 2012 to 2017 it rose by 30%.[97] The data for 31 December 2017 showed 1873 animals living in Poland of which 1635 are in free-range herds.[98] The data for 31 December 2016 showed 1698 zubrs living in Poland of which 1455 were in free-range herds.[99] As of 2014 they were 1434 wisents, out of which 1212 were in free-range herds, and 522 belonged to the wild population in the Białowieża Forest. Compared to 2013, the total population in 2014 increased by 4.1%, while the free-ranging population increased by 6.5%.[80] Bison from Poland have also been transported beyond the country's borders to boost the local populations of other countries, among them Bulgaria, Spain, Romania, Czechia, and others.[100] Poland has been described as the world's breeding centre of the European bison.[21] As of 31 December 2019 data - out of 2269 zubrs, 2048 were free-roaming and 221 were living in captivity, including zoos.A total of 770 belonged to the wild population in the Białowieża Forest and 668 to Bieszczady National Park. As the numbers of animals is growing, more zubrs are spotted in areas where they have not been seen in centuries, especially migrating males in Spring. According to National Forests programme the next place where about 40 free-roaming zubrs will be placed is the Lublin Region (Lasy Janowskie) in 2020 and 2021. This new location announcement resulted in effecting ecologists' efforts to redesign some bridges of the S19 highway (which will be constructed in years 2020 - 2022 to allow large animals to cross it).[101] Romania: The wisents were reintroduced in 1958, when the first two animals were brought from Poland and kept in a reserve in Hațeg. Similar locations later appeared in Vama Buzăului (Valea Zimbrilor Nature Reserve) and Bucșani, Dâmbovița. The idea of free bison, on the Romanian territory, was born in 1999, through a program supported by the World Bank and the European Union.[102] Almost 100 free-roaming animals, as of 2019, population slowly increasing in the three areas where wild bison can be found: Northern Romania – Vânători-Neamț Natural Park, and South-West Romania – Țarcu Mountains and Poiana Ruscă Mountains, as part of the Life-Bison project initiated by WWF Romania and Rewilding Europe, with co-funding from the EU through its LIFE Programme. The wisents were reintroduced in 1958, when the first two animals were brought from Poland and kept in a reserve in Hațeg. Similar locations later appeared in Vama Buzăului (Valea Zimbrilor Nature Reserve) and Bucșani, Dâmbovița. The idea of free bison, on the Romanian territory, was born in 1999, through a program supported by the World Bank and the European Union.[102]

Romania: The wisents were reintroduced in 1958, when the first two animals were brought from Poland and kept in a reserve in Hațeg. Similar locations later appeared in Vama Buzăului (Valea Zimbrilor Nature Reserve) and Bucșani, Dâmbovița. The idea of free bison, on the Romanian territory, was born in 1999, through a program supported by the World Bank and the European Union.[102] Almost 100 free-roaming animals, as of 2019, population slowly increasing in the three areas where wild bison can be found: Northern Romania – Vânători-Neamț Natural Park, and South-West Romania – Țarcu Mountains and Poiana Ruscă Mountains, as part of the Life-Bison project initiated by WWF Romania and Rewilding Europe, with co-funding from the EU through its LIFE Programme. The wisents were reintroduced in 1958, when the first two animals were brought from Poland and kept in a reserve in Hațeg. Similar locations later appeared in Vama Buzăului (Valea Zimbrilor Nature Reserve) and Bucșani, Dâmbovița. The idea of free bison, on the Romanian territory, was born in 1999, through a program supported by the World Bank and the European Union.[102] Russia: Around 461, population generally stable and increasing.[103]

Russia: Around 461, population generally stable and increasing.[103] Slovakia: A bison reserve was established in Topoľčianky in 1958.[104] The reserve has a maximum capacity of 13 animals but has bred around 180 animals for various zoos. As of 2013, there was also a wild breeding herd of 16 animals in Poloniny National Park with an increasing population.[105]

Slovakia: A bison reserve was established in Topoľčianky in 1958.[104] The reserve has a maximum capacity of 13 animals but has bred around 180 animals for various zoos. As of 2013, there was also a wild breeding herd of 16 animals in Poloniny National Park with an increasing population.[105] Spain: Two herds in northern Spain were established in 2010.[106] As of 2018, the total population neared a hundred animals, half of them in Castile and León, but also in Asturias, Valencia, Extremadura and the Pyrenees.[107]

Spain: Two herds in northern Spain were established in 2010.[106] As of 2018, the total population neared a hundred animals, half of them in Castile and León, but also in Asturias, Valencia, Extremadura and the Pyrenees.[107] Sweden: There are approximately 139 animals.[81]

Sweden: There are approximately 139 animals.[81] Switzerland: Coming from Poland, one male and four females have been introduced in November 2019 into the natural reserve and forest of Suchy, Vaud Canton, western Switzerland. On 15 June, 2020, the first baby was born.[108][109]

Switzerland: Coming from Poland, one male and four females have been introduced in November 2019 into the natural reserve and forest of Suchy, Vaud Canton, western Switzerland. On 15 June, 2020, the first baby was born.[108][109] Ukraine: A population of around 240 animals, population is unstable and decreasing.[110]

Ukraine: A population of around 240 animals, population is unstable and decreasing.[110]

Distribution

The largest zubr herds — of both captive and wild populations — are still based in Poland and Belarus,[7] the majority of which can be found in the Białowieża Forest including the most numerous population of free-living European bison in the world with most of the animals living on the Polish side of the border.[72] Poland remains the world's breeding centre for the wisent.[21] In the years 1945 to 2014, from the Białowieża National Park alone, 553 specimens were sent to most captive populations of the zubr in Europe as well as all breeding sanctuaries for the species in Poland.[72]

Since 1983, a small reintroduced population lives in the Altai Mountains. This population suffers from inbreeding depression and needs the introduction of unrelated animals for "blood refreshment". In the long term, authorities hope to establish a population of about 1,000 animals in the area. One of the northernmost current populations of the European bison lives in Vologodskaya Oblast in the Northern Dvina valley at about 60°N. It survives without supplementary winter feeding. Another Russian population lives in the forests around the Desna River on the border between Russia and Ukraine.[38] The north-easternmost population lives in Pleistocene Park south of Chersky in Siberia, a project to recreate the steppe ecosystem which began to be altered 10,000 years ago. Five wisents were introduced on 24 April 2011. The wisents were brought to the park from the Prioksko-Terrasny Nature Reserve near Moscow. Winter temperatures often drop below −50 °C. Four of the five bison have subsequently died due to problems acclimatizing to the low winter temperature.

In 2011, three bison were introduced into Alladale Wilderness Reserve in Scotland. Plans to move more into the reserve were made, but the project failed due to not being "well thought through".[111] In April 2013, eight European bison (one male, five females, and two calves) were released into the wild in the Bad Berleburg region of Germany,[112] after 850 years of absence since the species became extinct in that region.[113]

Plans are being made to reintroduce two herds in Germany[114] and in the Netherlands in Oostvaardersplassen Nature Reserve[115] in Flevoland as well as the Veluwe. In 2007, a bison pilot project in a fenced area was begun in Zuid-Kennemerland National Park in the Netherlands.[116] Because of their limited genetic pool, they are considered highly vulnerable to illnesses such as foot-and-mouth disease. In March 2016, a herd was released in the Maashorst Nature Reserve in North Brabant. Zoos in 30 countries also have quite a few bison involved in captive-breeding programs.

Cultural significance

Representations of the European bison from different ages, across millennia of human society's existence, can be found throughout Eurasia in the form of drawings and rock carvings; one of the oldest and most famous instances of the latter can be found in the Cave of Altamira, present-day Spain, where cave art featuring the wisent from the Upper Paleolithic was discovered.[117] The bison has also been represented in a wide range of art in human history, such as sculptures, paintings, photographs, glass art, and more.[118] Sculptures of the wisent constructed in the 19th and 20th centuries continue to stand in a number of European cities; arguably the most notable of these are the zubr statue in Spała from 1862 designed by Mihály Zichy and the two bison sculptures in Kiel sculpted by August Gaul in 1910–1913. However, a number of other monuments to the animal also exist, such as those in Hajnówka and Pszczyna or at the Kyiv Zoo entrance.[118][117] Mikołaj Hussowczyk, a poet writing in Latin about the Grand Duchy of Lithuania during the early 16th century, described the zubr in a historically significant fictional work from 1523.[119]

The zubr is considered one of the national animals of Poland and Belarus.[6] Due to this and the fact that half of the worldwide European bison population can be found spread across these two countries,[7] the wisent is still featured prominently in the heraldry of these neighbouring states (especially in the overlapping region of Eastern Poland and Western Belarus).[118] Examples in Poland include the coats of arms of: the counties of Hajnówka and Zambrów, the towns Sokółka and Żywiec, the villages Białowieża and Narewka, as well as the coats of arms of the Pomian and Wieniawa families. Examples in Belarus include the Grodno and Brest voblasts, the town of Svislach, and others. The European bison can also be found on the coats of arms of places in neighbouring countries: Perloja in southern Lithuania, Lypovets in west-central Ukraine, and Zubří in east Czechia – as well as further outside the region, such as Kortezubi in the Basque Country, and Jabel in Germany.

A flavoured vodka called Żubrówka ([ʐuˈbrufka]), originating as a recipe of the szlachta of the Kingdom of Poland in the 14th century, has since 1928 been industrially produced as a brand in Poland.[120] In the decades that followed, it became known as the "world's best known Polish vodka"[121] and sparked the creation of a number of copy brands inspired by the original in Belarus, Russia, Germany, as well as other brands in Poland.[122] The original Polish brand is known for placing a decorative blade of bison grass from the Białowieża Forest in each bottle of their product; both the plant's name in Polish and the vodka are named after żubr, the Polish name for the European bison.[120] The zubr also appears commercially as a symbol of a number of other Polish brands, such as the popular beer brand Żubr and on the logo of Poland's second largest bank, Bank Pekao S.A..[118]

See also

Notes

References

- Plumb, G.; Kowalczyk, R. & Hernandez-Blanco, J.A. (2020). "Bison bonasus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T2814A45156279. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- "70 years Wisent in the Caucasian mountains". www.lhnet.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- The Higgs Bison – mystery species hidden in cave art, The University of Adelaide, 19 October 2016, retrieved 13 January 2017

- Palacio, Pauline; Berthonaud, Véronique; et al. (1 January 2017). "Genome data on the extinct Bison schoetensacki establish it as a sister species of the extant European bison (Bison bonasus)". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 17 (1): 48. doi:10.1186/s12862-017-0894-2. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 5303235. PMID 28187706.

- Marsolier-Kergoat, Marie-Claude; Palacio, Pauline; et al. (17 June 2015). "Hunting the Extinct Steppe Bison (Bison priscus) Mitochondrial Genome in the Trois-Frères Paleolithic Painted Cave". PLOS ONE. 10 (6): e0128267. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1028267M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128267. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4471230. PMID 26083419.

- "Poland". All About Bison. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Wójcik, Wojciech (director & script); Zielonka, Tomasz (lead) (2 November 2019). Las bliżej nas – Polskie żubry [The Forest Closer to Us – Polish Bison] (Documentary). Poland: Telewizja Polska.

- bison, n. Oxford English Dictionary (online 2nd ed.). 2011 [1989]. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- Αριστοτέλης 4th century BC: Των περί τα ζώα ιστοριών.

- wisent, n. Oxford English Dictionary (online 2nd ed.). 1989 [1928]. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- Weissenborn, W. (1838). "On the Influence of Man in modifying the Zoological Featurs of the Globe; with Statistical Accounts respecting a few of the more important Species". The Magazine of Natural History. 2.

- Wilson, James (1831). "Essay III: On the origin and natural history of the domestic ox, and its allied species". Journal of Agriculture. 2.

- Jagodziński, Grzegorz (2008). "Nieindoeuropejskie słownictwo w germańskim". Retrieved 30 November 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Semenov U.A. of WWF-Russia, 2014, "The Wisents of Karachay-Cherkessia", Proceedings of the Sochi National Park (8), pp.23–24, ISBN 978-5-87317-984-8, KMK Scientific Press

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "European Bison: The Animal Files".

- "torontozoo.com (2011)". Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Boitani, Luigi, Simon & Schuster's Guide to Mammals. Simon & Schuster/Touchstone Books (1984), ISBN 978-0-671-42805-1

- Burnie D and Wilson DE (Eds.), Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. DK Adult (2005), ISBN 0789477645

- Gennady G. Boeskorov, Olga R. Potapova, Albert V. Protopopov, Valery V. Plotnikov, Larry D. Agenbroad, Konstantin S. Kirikov, Innokenty S. Pavlov, Marina V. Shchelchkova, Innocenty N. Belolyubskii, Mikhail D. Tomshin, Rafal Kowalczyk, Sergey P. Davydov, Stanislav D. Kolesov, Alexey N. Tikhonov, Johannes van der Plicht, 2016, "The Yukagir Bison: The exterior morphology of a complete frozen mummy of the extinct steppe bison, Bison priscus from the early Holocene of northern Yakutia, Russia", pp.7, Quaternary International, Vol.406 (25 June 2016), Part B, pp.94–110

- "The royal European bison". Łowiec Polski. 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Soubrier, J.; Gower, G.; Chen, K.; Richards, S. M.; Llamas, B.; Mitchell, K. J.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Kosintsev, P.; Lee, M. S. Y.; Baryshnikov, G.; Bollongino, R.; Bover, P.; Burger, J.; Chivall, D.; Crégut-Bonnoure, E.; Decker, J. E.; Doronichev, V. B.; Douka, K.; Fordham, D. A.; Fontana, F.; Fritz, C.; Glimmerveen, J.; Golovanova, L. V.; Groves, C.; Guerreschi, A.; Haak, W.; Higham, T.; Hofman-Kamińska, E.; Immel, A.; Julien, M.-A.; Krause, J.; Krotova, O.; Langbein, F.; Larson, G.; Rohrlach, A.; Scheu, A.; Schnabel, R. D.; Taylor, J. F.; Tokarska, M.; Tosello, G.; van der Plicht, J.; van Loenen, A.; Vigne, J.-D.; Wooley, O.; Orlando, L.; Kowalczyk, R.; Shapiro, B.; Cooper, A. (18 October 2016). "Early cave art and ancient DNA record the origin of European bison". Nature Communications. 7 (13158): 13158. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713158S. doi:10.1038/ncomms13158. PMC 5071849. PMID 27754477.

- The Holocene distribution of European bison – the archaeozoological record. Norbert Benecke. Munibe (Antropologia_Arkeologia) 57 421–428 2005. ISSN 1132-2217. Refers to Liljegren R. and Ekstrom J., 1996. The terrestrial late Glacial fauna in south Sweden. In L. Larsson (Hrsg). The earliest settlement of Scandinavia and its relationship with neighbouring areas. Acta Archaeologica Lundensia 8, 24, 135–139, Stockholm.

- The Holocene distribution of European bison-the archaeozoological record.

- Kirkdale Cave (Pleistocene of the United Kingdom)

- Bison Teeth & Bones

- Benedict Macdonaldo, 2019, Rebirding: Rewilding Britain and its Birds, The chaos animals, Pelagic Publishing. Ltd

- Bison

- Markova, A.K.; et al. (2015). "Changes in the Eurasian distribution of the musk ox (Ovibos moschatus) and the extinct bison (Bison priscus) during the last 50 ka BP". Quaternary International. 378: 99–110. Bibcode:2015QuInt.378...99M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.01.020.

- Zazula, Grant D.; Hall, Elizabeth; Hare, P. Gregory; Thomas, Christian; Mathewes, Rolf; La Farge, Catherine; Martel, André L.; Heintzman, Peter D.; Shapiro, Beth (2017). "A middle Holocene steppe bison and paleoenvironments from the Versleuce Meadows, Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 54 (11): 1138–1152. Bibcode:2017CaJES..54.1138Z. doi:10.1139/cjes-2017-0100. hdl:1807/78639.

- Briggs, H. (19 October 2016). "Cave paintings reveal clues to mystery Ice Age beast". BBC.com. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- Παυσανίας 2nd cent A.D.: Ελλάδος περιήγησης. Φωκικά, Λοκρών Οζόλων.

- Douglas, N. 1927: Birds and Beasts of the Greek Anthology. Florence.

- Kitchell, K.F. 2013: Animals in the Ancient Word from A to Z.

- Spassov, N., Iliev, N. 1986: Bone remains of Wisent (Bison bonasus L.) in the medieval settlement near the Garvan village, Silistra District (new researches). In: Vazharova, Zh. The Medieval Settlement at Garvan Village, Silistra District, 4th–11th century A. D., Sofia, Publ. House of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 68.

- Onar, V., Soubrier, J., Toker, N.Y., Loenen, v.A., Llamas, B., Siddiq, B.A., Pasicka, E. & M. Tokarska 2016: Did the historical range of the European bison (Bison bonasus L.) extend further south?—a new finding from the Yenikapı Metro and Marmaray excavation, Turkey. Mammal Research 62(1): 103–109.

- European Bison (Bison bonasus): Current State of the Species and Strategy for Its Conservation By Zdzsław Pucek, Published by Council of Europe, 2004, ISBN 92-871-5549-6, 978-92-871-5549-8

- Sipko, T., P. (2009). European bison in Russia – past, present and future. European Bison Conservation Newsletter Vol 2, pp: 148–159

- "Lake Pape – Bison", World Wide Fund for Nature Archived 13 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Z. Pucek, I. P. Belousova, Z. A. Krasiński, M. Krasińska and W. Olech (10 October 2003). "European bison (Bison bonasus) Current state of the species and an action plan for its conservation". Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "European Bison – Information about the species". European Bison Conservation Center. 2018. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- "Nils Seethaler hat zur Person Julius Riemer geforscht". Wittenberger Sonntag/Freizeit Magazin (in German). FIW mbH & Co. KG. 10 May 2019.

- Urmacher unerwünscht. Berliner Zoo. In: Der Spiegel vom 23. Juni 1954.

- Frank G. Wörner: DER WISENT – Ein Erfolg des Artenschutzes: Notizen zur Rettung und Rückkehr eines Giganten. In: Veröffentlichungen des Tierparks Niederfischbach gemeinsam mit dem regionalen Naturschutzverein Ebertseifen Lebensräume e. V., 2006.

- "Zagłada i restytucja żubrów". www.oep.neostrada.pl. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Ley, Willy (December 1964). "The Rarest Animals". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–103.

- Verkaar, EL; Nijman, IJ; Beeke, M; Hanekamp, E; Lenstra, JA (2004). "Maternal and Paternal Lineages in Cross-Breeding Bovine Species. Has Wisent a Hybrid Origin?" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (7): 1165–70. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh064. PMID 14739241.

- Buntjer, J B; Otsen, M; Nijman, I J; Kuiper, M T R; Lenstra, J A (2002). "Phylogeny of bovine species based on AFLP fingerprinting". Heredity. 88 (1): 46–51. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800007. PMID 11813106.

- Gautier, M.; Moazami-Goudarzi, K.; Leveziel, H.; Parinello, H.; Grohs, C.; Rialle, S. J.; Kowalczyk, R.; Flori, L (2016). "Deciphering the wisent demographic and adaptive histories from individual whole-genome sequences". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 33 (11): 2801–2814. doi:10.1093/molbev/msw144. PMC 5062319. PMID 27436010.

- Massilani, Diyendo; Guimaraes, Silvia; Brugal, Jean-Philip; Bennett, E. Andrew; Tokarska, Malgorzata; Arbogast, Rose-Marie; Baryshnikov, Gennady; Boeskorov, Gennady; Castel, Jean-Christophe; Davydov, Sergey; Madelaine, Stéphane; Putelat, Olivier; Spasskaya, Natalia N.; Uerpmann, Hans-Peter; Grange, Thierry; Geigl, Eva-Maria (21 October 2016). "Past climate changes, population dynamics and the origin of Bison in Europe". BMC Biology. 14 (93): 93. doi:10.1186/s12915-016-0317-7. PMC 5075162. PMID 27769298.

- Mirosław Androsiuk (26 January 2012). "Leśnicy wołają żubry na siano". TVN Meteo.

- Marta Kądziela (Director) (24 September 2014). Ocalony Świat – odc. 2 – Leśny majestat [Saved World – Episode 2 – Forest Majesty] (Documentary). Poland: TVP1.

- Sylwia Plucińska (6 April 2010). "Żubr dostał kosza, więc uciekł z pszczyńskiego rezerwatu". Dziennik Zachodni.

- Medeiros, Luísa (3 September 2009). "Female European bison in Brasília Zoo may be the species oldest". correiobraziliense.com.br. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2009.(in Portuguese)

- "ŻubryOnline". Lasy Państwowe. 4 November 2019.

- Pucek, Z.; Belousova, I.P.; Krasiñska, M.; Krasiñski, Z.A. & Olech, W. (2004). European Bison Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.: IUCN/SSC Bison Specialist Group.

- Brent Huffman. "Ultimate Ungulate".

- Olech, W. (2011). Pers. comm.

- The Penny Cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge by Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Great Britain), published by C. Knight, 1835

- Trophy Bowhunting: Plan the Hunt of a Lifetime and Bag One for the Record Books, by Rick Sapp, Edition: illustrated, published by Stackpole Books, 2006, ISBN 0-8117-3315-7, 978-0-8117-3315-1

- American Bison: A Natural History, By Dale F. Lott, Harry W. Greene, ebrary, Inc., Contributor Harry W. Greene, Edition: illustrated, Published by University of California Press, 2003 ISBN 0-520-24062-6, 978-0-520-24062-9

- Zoologist: A Monthly Journal of Natural History, By Edward Newman, James Edmund Harting, Published by J. Van Voorst, 1859

- Trapani, J. "Bison bonasus". Animal Diversity Web.

- Krasińska, M.; Krasiński, Z. (2007). European bison – the nature monograph. Białowieża, Poland.: Mammal Research Institute.

- Macdonald, D. (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- "Genetic status of the species". Bison Specialist Group – Europe. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "The Extinction Website – Species Info – Caucasian European Bison". www.petermaas.nl. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- Belousova, Irina P. (2004). European bison : status survey and conservation action plan. Pucek, Zdzisław,, Belousova, Irina P.,, Krasińska, Małgorzata. compiler., Krasiński, Zbigniew A., 1938–, Olech, Wanda,, IUCN/SSC Bison Specialist Group. Gland. p. 16. ISBN 2831707625. OCLC 56807539.

- "Wisents in Slovakia: the population has increased three times since 2004". European Wildlife. 23 July 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- "Die Wisente kehren nach Deutschland zurück – Wissen & Umwelt". Deutsche Welle. 11 April 2013.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330546518_Spatio-temporal_distribution_of_European_bison_Bison_bonasus_L_in_Poloniny_National_Park_East_Carpathians_Slovakia

- "Puszcza Białowieska ostoją żubrów". Białowieski Park Narodowy. 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- "Bison in the Republic of Moldova" Archived 6 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, IATP

- "El bisonte europeo se reimplanta en España". Univision.com. 5 June 2010. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- "Denmark's Bornholm island gets rare bison from Poland". bbc.co.uk. 7 June 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- "Wisent rescue in Europe is only at the half-way point". European WILDLIFE. 13 January 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- GrrlScientist (20 July 2020). "Bison To Return To British Woodland After Absence Of More Than Six Millennia". Forbes. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "European bison to be introduced into Kent woodland". BBC News. 9 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Chantler-Hicks, Lydia (10 July 2020). "Bison to be introduced to Kent woodland". Kent Online. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Number of wisents in the Czech Republic passes one hundred for the first time since the Middle Ages". European Wildlife. 13 March 2018. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- "All About Bison:Europe".

- "Почему 2 тысячи зубров – очень мало для Беларуси?". sb.by (in Russian). 17 March 2020.

- Pucek, Zdzsław (1 January 2004). European Bison (Bison Bonasus): Current State of the Species and Strategies for its Conservation. p. 15. ISBN 9789287155498.

- "European Bison Brought back to Bulgaria". 9 November 2013.

- "Denmark's Bornholm island gets rare bison from Poland". BBC News. 7 June 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- "Polski żubr zastrzelony w niemieckim miasteczku. Jest decyzja". 26 June 2018.

- "Germany's 'first wild bison in 250 years' shot dead by authorities". 20 September 2017.

- "orseginemzetipark.hu: Európai bölények az Őrségi Nemzeti Parkban".

- "kmnp.nemzetipark.gov.hu: Körösvölgyi Látogatóközpont és Állatpark".

- "Mįslė gamtosaugininkams: kaip visą būrį stumbrų perkelti į Dzūkiją". DELFI. 9 January 2018.

- Invitat, Author (27 August 2005). "The Bison Come Back to Moldova". Moldova.org. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Belarus, Moldova discuss bison exchange program". Ministry of Forestry of the Republic of Belarus. 17 February 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "History | Wisentproject Kraansvlak". www.wisenten.nl. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "Wisent Maashorst". ARK Natuurontwikkeling (in Dutch). 17 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "Wisent op de Veluwe". Stichting Wisent op de Veluwe (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- https://smz.waw.pl/wyniki-inwentaryzacji-zubrow-w-polsce/

- Professor Wanda Olech-Piasecka (10 January 2017). Ochrona żubra w Polsce. Wyjaśniamy kontrowersje [Protection of the zubr in Poland. We explain the controversies] (Interview). Poland: Telewizja Lasów Państwowych.

- "Wiemy, ile żubrów żyje w Polsce / Aktualne wiadomości z Polski, informacje rolnicze z kraju, wydarzenia / Agropolska". 6 April 2018.

- "Liczba żubrów w Polsce i na świecie".

- 90 lat ochrony żubra [90 Years of Zubr Protection] (Video). Poland: Lasy Państwowe. 11 September 2019.

- https://www.dziennikwschodni.pl/janow-lubelski/zubry-w-lasach-janowskich-to-moze-byc-blad-alarmuja-ekolodzy-przez-droge-s19,n,1000251873.html

- Gheorghe, Dan (24 July 2011). "Uriașii din Carpați" [The giants of the Carpathians] (in Romanian). romanialibera.ro. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Morris, Desmond (5 May 2015). Bison. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780234571.

- "Zubria zvernica Topolčianky".

- "Zubři na Slovensku: populace se od roku 2004 zvětšila téměř čtyřnásobně". Česká krajina.

- OKIA (9 October 2012). "Biggest bison transport ever Rewilding Europe".

- "Segovia recibe nueve bisontes europeos para evitar su extinción". 20 Minutos. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Cinq bisons sont arrivés dans la forêt de Suchy".

- "Bisons: première naissance dans la forêt de Suchy (VD)".

- Parnikoza, Ivan. "BISON YEAR IN UKRAINE". Terrestrial ecosystems research. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bison return to Germany after 300-year absence. Mongabay.com

- Christoph Vetter (1 March 2010). "Wisente erobern die ITB". Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (WAZ), online edition. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- "Startseite – Wisent Welt".

- "Second group of 3 European bison from Poland (Białowieża) was released today". Large Herbivore Network. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- "Bison". Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- Sztych, D. (2014). "Żubr w kulturze". Życie Weterynaryjne. 89 (10): 857–865.

- Sztych, D. (2008). "Kulturotwórcza rola żubra". European Bison Conservation Newsletter. 1 (2008): 161–190.

- Дарашкевіч, Віктар (1980). Паэма жыцця // Песня пра зубра. Minsk. pp. 171–184.

- Janka Werpachowska (25 December 2010). "Żubrówka – kultowa wódka z trawką. Powstawanie, historia, drinki". Kurier Poranny.

- "Żubrówka". Roust. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Patryk Słowik (4 August 2015). "Nie każdy może sprzedawć "żubrówkę". Witas: Nie tolerujemy, gdy ktoś do butelki wkłada trawę". Gazeta Prawna.

This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "European bison" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bison bonasus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to European bison. |

- European bison media from ARKive

- Bison entry from Walker's Mammals of the World

- The Extinction Website – Caucasian European bison (Bison bonasus caucasicus).

- The Extinction Website – Carpathian European bison (Bison bonasus hungarorum).

- European bison/wisent

- BBC NEWS Reversal fortunes

- I. Parnikoza, V. Boreiko, V. Sesin, M. Kaliuzhna History, current state and perspectives of conservation of European bison in Ukraine // European Bison Conservation Newsletter Vol 2 (2009) pp: 5–16

- Species fact sheet on LHNet database

- "Wisent online" from Browsk Forest District in Białowieża National Park, Poland

- National Geographic – Rewilding Europe Brings Back the Continent's Largest Land Animal

- European Bison Conservation Center

- Rewilding bison in Romania

- Distribution and quantity of the European bison in 2014 Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine (PDF; 213 kB)