Concept

Concepts are defined as abstract ideas or general notions that occur in the mind, in speech, or in thought. They are understood to be the fundamental building blocks of thoughts and beliefs. They play an important role in all aspects of cognition.[1][2] As such, concepts are studied by several disciplines, such as linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, and these disciplines are interested in the logical and psychological structure of concepts, and how they are put together to form thoughts and sentences. The study of concepts has served as an important flagship of an emerging interdisciplinary approach called cognitive science.[3]

In contemporary philosophy, there are at least three prevailing ways to understand what a concept is:[4]

- Concepts as mental representations, where concepts are entities that exist in the mind (mental objects)

- Concepts as abilities, where concepts are abilities peculiar to cognitive agents (mental states)

- Concepts as Fregean senses (see sense and reference), where concepts are abstract objects, as opposed to mental objects and mental states

Concepts can be organized into a hierarchy, higher levels of which are termed "superordinate" and lower levels termed "subordinate". Additionally, there is the "basic" or "middle" level at which people will most readily categorize a concept.[5] For example, a basic-level concept would be "chair", with its superordinate, "furniture", and its subordinate, "easy chair".

A concept is instantiated (reified) by all of its actual or potential instances, whether these are things in the real world or other ideas.

Concepts are studied as components of human cognition in the cognitive science disciplines of linguistics, psychology and, philosophy, where an ongoing debate asks whether all cognition must occur through concepts. Concepts are used as formal tools or models in mathematics, computer science, databases and artificial intelligence where they are sometimes called classes, schema or categories. In informal use the word concept often just means any idea.

Ontology of concepts

A central question in the study of concepts is the question of what they are. Philosophers construe this question as one about the ontology of concepts—what kind of things they are. The ontology of concepts determines the answer to other questions, such as how to integrate concepts into a wider theory of the mind, what functions are allowed or disallowed by a concept's ontology, etc. There are two main views of the ontology of concepts: (1) Concepts are abstract objects, and (2) concepts are mental representations.[6]

Concepts as mental representations

The psychological view of concepts

Within the framework of the representational theory of mind, the structural position of concepts can be understood as follows: Concepts serve as the building blocks of what are called mental representations (colloquially understood as ideas in the mind). Mental representations, in turn, are the building blocks of what are called propositional attitudes (colloquially understood as the stances or perspectives we take towards ideas, be it "believing", "doubting", "wondering", "accepting", etc.). And these propositional attitudes, in turn, are the building blocks of our understanding of thoughts that populate everyday life, as well as folk psychology. In this way, we have an analysis that ties our common everyday understanding of thoughts down to the scientific and philosophical understanding of concepts.[7]

The physicalist view of concepts

In a physicalist theory of mind, a concept is a mental representation, which the brain uses to denote a class of things in the world. This is to say that it is literally, a symbol or group of symbols together made from the physical material of the brain.[8][9] Concepts are mental representations that allow us to draw appropriate inferences about the type of entities we encounter in our everyday lives.[9] Concepts do not encompass all mental representations, but are merely a subset of them.[8] The use of concepts is necessary to cognitive processes such as categorization, memory, decision making, learning, and inference.[10]

Concepts are thought to be stored in long term cortical memory,[11] in contrast to episodic memory of the particular objects and events which they abstract, which are stored in hippocampus. Evidence for this separation comes from hippocampal damaged patients such as patient HM. The abstraction from the day's hippocampal events and objects into cortical concepts is often considered to be the computation underlying (some stages of) sleep and dreaming. Many people (beginning with Aristotle) report memories of dreams which appear to mix the day's events with analogous or related historical concepts and memories, and suggest that they were being sorted or organised into more abstract concepts. ("Sort" is itself another word for concept, and "sorting" thus means to organise into concepts.)

Concepts as abstract objects

The semantic view of concepts suggests that concepts are abstract objects. In this view, concepts are abstract objects of a category out of a human's mind rather than some mental representations. [6]

There is debate as to the relationship between concepts and natural language.[4] However, it is necessary at least to begin by understanding that the concept "dog" is philosophically distinct from the things in the world grouped by this concept—or the reference class or extension.[8] Concepts that can be equated to a single word are called "lexical concepts".[4]

Study of concepts and conceptual structure falls into the disciplines of linguistics, philosophy, psychology, and cognitive science.[9]

In the simplest terms, a concept is a name or label that regards or treats an abstraction as if it had concrete or material existence, such as a person, a place, or a thing. It may represent a natural object that exists in the real world like a tree, an animal, a stone, etc. It may also name an artificial (man-made) object like a chair, computer, house, etc. Abstract ideas and knowledge domains such as freedom, equality, science, happiness, etc., are also symbolized by concepts. It is important to realize that a concept is merely a symbol, a representation of the abstraction. The word is not to be mistaken for the thing. For example, the word "moon" (a concept) is not the large, bright, shape-changing object up in the sky, but only represents that celestial object. Concepts are created (named) to describe, explain and capture reality as it is known and understood.

A priori concepts

Kant maintained the view that human minds possess pure or a priori concepts. Instead of being abstracted from individual perceptions, like empirical concepts, they originate in the mind itself. He called these concepts categories, in the sense of the word that means predicate, attribute, characteristic, or quality. But these pure categories are predicates of things in general, not of a particular thing. According to Kant, there are twelve categories that constitute the understanding of phenomenal objects. Each category is that one predicate which is common to multiple empirical concepts. In order to explain how an a priori concept can relate to individual phenomena, in a manner analogous to an a posteriori concept, Kant employed the technical concept of the schema. He held that the account of the concept as an abstraction of experience is only partly correct. He called those concepts that result from abstraction "a posteriori concepts" (meaning concepts that arise out of experience). An empirical or an a posteriori concept is a general representation (Vorstellung) or non-specific thought of that which is common to several specific perceived objects (Logic, I, 1., §1, Note 1)

A concept is a common feature or characteristic. Kant investigated the way that empirical a posteriori concepts are created.

The logical acts of the understanding by which concepts are generated as to their form are:

- comparison, i.e., the likening of mental images to one another in relation to the unity of consciousness;

- reflection, i.e., the going back over different mental images, how they can be comprehended in one consciousness; and finally

- abstraction or the segregation of everything else by which the mental images differ ...

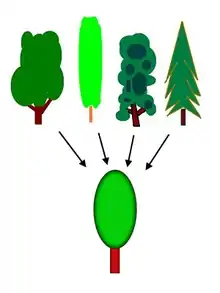

In order to make our mental images into concepts, one must thus be able to compare, reflect, and abstract, for these three logical operations of the understanding are essential and general conditions of generating any concept whatever. For example, I see a fir, a willow, and a linden. In firstly comparing these objects, I notice that they are different from one another in respect of trunk, branches, leaves, and the like; further, however, I reflect only on what they have in common, the trunk, the branches, the leaves themselves, and abstract from their size, shape, and so forth; thus I gain a concept of a tree.

— Logic, §6

Embodied content

In cognitive linguistics, abstract concepts are transformations of concrete concepts derived from embodied experience. The mechanism of transformation is structural mapping, in which properties of two or more source domains are selectively mapped onto a blended space (Fauconnier & Turner, 1995; see conceptual blending). A common class of blends are metaphors. This theory contrasts with the rationalist view that concepts are perceptions (or recollections, in Plato's term) of an independently existing world of ideas, in that it denies the existence of any such realm. It also contrasts with the empiricist view that concepts are abstract generalizations of individual experiences, because the contingent and bodily experience is preserved in a concept, and not abstracted away. While the perspective is compatible with Jamesian pragmatism, the notion of the transformation of embodied concepts through structural mapping makes a distinct contribution to the problem of concept formation.

Realist universal concepts

Platonist views of the mind construe concepts as abstract objects.[12] Plato was the starkest proponent of the realist thesis of universal concepts. By his view, concepts (and ideas in general) are innate ideas that were instantiations of a transcendental world of pure forms that lay behind the veil of the physical world. In this way, universals were explained as transcendent objects. Needless to say this form of realism was tied deeply with Plato's ontological projects. This remark on Plato is not of merely historical interest. For example, the view that numbers are Platonic objects was revived by Kurt Gödel as a result of certain puzzles that he took to arise from the phenomenological accounts.[13]

Sense and reference

Gottlob Frege, founder of the analytic tradition in philosophy, famously argued for the analysis of language in terms of sense and reference. For him, the sense of an expression in language describes a certain state of affairs in the world, namely, the way that some object is presented. Since many commentators view the notion of sense as identical to the notion of concept, and Frege regards senses as the linguistic representations of states of affairs in the world, it seems to follow that we may understand concepts as the manner in which we grasp the world. Accordingly, concepts (as senses) have an ontological status.[6]

Concepts in calculus

According to Carl Benjamin Boyer, in the introduction to his The History of the Calculus and its Conceptual Development, concepts in calculus do not refer to perceptions. As long as the concepts are useful and mutually compatible, they are accepted on their own. For example, the concepts of the derivative and the integral are not considered to refer to spatial or temporal perceptions of the external world of experience. Neither are they related in any way to mysterious limits in which quantities are on the verge of nascence or evanescence, that is, coming into or going out of existence. The abstract concepts are now considered to be totally autonomous, even though they originated from the process of abstracting or taking away qualities from perceptions until only the common, essential attributes remained.

Notable theories on the structure of concepts

Classical theory

The classical theory of concepts, also referred to as the empiricist theory of concepts,[8] is the oldest theory about the structure of concepts (it can be traced back to Aristotle[9]), and was prominently held until the 1970s.[9] The classical theory of concepts says that concepts have a definitional structure.[4] Adequate definitions of the kind required by this theory usually take the form of a list of features. These features must have two important qualities to provide a comprehensive definition.[9] Features entailed by the definition of a concept must be both necessary and sufficient for membership in the class of things covered by a particular concept.[9] A feature is considered necessary if every member of the denoted class has that feature. A feature is considered sufficient if something has all the parts required by the definition.[9] For example, the classic example bachelor is said to be defined by unmarried and man.[4] An entity is a bachelor (by this definition) if and only if it is both unmarried and a man. To check whether something is a member of the class, you compare its qualities to the features in the definition.[8] Another key part of this theory is that it obeys the law of the excluded middle, which means that there are no partial members of a class, you are either in or out.[9]

The classical theory persisted for so long unquestioned because it seemed intuitively correct and has great explanatory power. It can explain how concepts would be acquired, how we use them to categorize and how we use the structure of a concept to determine its referent class.[4] In fact, for many years it was one of the major activities in philosophy—concept analysis.[4] Concept analysis is the act of trying to articulate the necessary and sufficient conditions for the membership in the referent class of a concept. For example, Shoemaker's classic "Time Without Change" explored whether the concept of the flow of time can include flows where no changes take place, though change is usually taken as a definition of time.

Arguments against the classical theory

Given that most later theories of concepts were born out of the rejection of some or all of the classical theory,[12] it seems appropriate to give an account of what might be wrong with this theory. In the 20th century, philosophers such as Wittgenstein and Rosch argued against the classical theory. There are six primary arguments[12] summarized as follows:

- It seems that there simply are no definitions—especially those based in sensory primitive concepts.[12]

- It seems as though there can be cases where our ignorance or error about a class means that we either don't know the definition of a concept, or have incorrect notions about what a definition of a particular concept might entail.[12]

- Quine's argument against analyticity in Two Dogmas of Empiricism also holds as an argument against definitions.[12]

- Some concepts have fuzzy membership. There are items for which it is vague whether or not they fall into (or out of) a particular referent class. This is not possible in the classical theory as everything has equal and full membership.[12]

- Rosch found typicality effects which cannot be explained by the classical theory of concepts, these sparked the prototype theory.[12] See below.

- Psychological experiments show no evidence for our using concepts as strict definitions.[12]

Prototype theory

Prototype theory came out of problems with the classical view of conceptual structure.[4] Prototype theory says that concepts specify properties that members of a class tend to possess, rather than must possess.[12] Wittgenstein, Rosch, Mervis, Berlin, Anglin, and Posner are a few of the key proponents and creators of this theory.[12][14] Wittgenstein describes the relationship between members of a class as family resemblances. There are not necessarily any necessary conditions for membership; a dog can still be a dog with only three legs.[9] This view is particularly supported by psychological experimental evidence for prototypicality effects.[9] Participants willingly and consistently rate objects in categories like 'vegetable' or 'furniture' as more or less typical of that class.[9][14] It seems that our categories are fuzzy psychologically, and so this structure has explanatory power.[9] We can judge an item's membership of the referent class of a concept by comparing it to the typical member—the most central member of the concept. If it is similar enough in the relevant ways, it will be cognitively admitted as a member of the relevant class of entities.[9] Rosch suggests that every category is represented by a central exemplar which embodies all or the maximum possible number of features of a given category.[9] Lech, Gunturkun, and Suchan explain that categorization involves many areas of the brain. Some of these are: visual association areas, prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and temporal lobe.

The Prototype perspective is proposed as an alternative view to the Classical approach. While the Classical theory requires an all-or-nothing membership in a group, prototypes allow for more fuzzy boundaries and are characterized by attributes.[15] Lakeoff stresses that experience and cognition are critical to the function of language, and Labov's experiment found that the function that an artifact contributed to what people categorized it as.[15] For example, a container holding mashed potatoes versus tea swayed people toward classifying them as a bowl and a cup, respectively. This experiment also illuminated the optimal dimensions of what the prototype for "cup" is.[15]

Prototypes also deal with the essence of things and to what extent they belong to a category. There have been a number of experiments dealing with questionnaires asking participants to rate something according to the extent to which it belongs to a category. [15]This question is contradictory to the Classical Theory because something is either a member of a category or is not.[15] This type of problem is paralleled in other areas of linguistics such as phonology, with an illogical question such as "is /i/ or /o/ a better vowel?" The Classical approach and Aristotelian categories may be a better descriptor in some cases.[15]

Theory-theory

Theory-theory is a reaction to the previous two theories and develops them further.[9] This theory postulates that categorization by concepts is something like scientific theorizing.[4] Concepts are not learned in isolation, but rather are learned as a part of our experiences with the world around us.[9] In this sense, concepts' structure relies on their relationships to other concepts as mandated by a particular mental theory about the state of the world.[12] How this is supposed to work is a little less clear than in the previous two theories, but is still a prominent and notable theory.[12] This is supposed to explain some of the issues of ignorance and error that come up in prototype and classical theories as concepts that are structured around each other seem to account for errors such as whale as a fish (this misconception came from an incorrect theory about what a whale is like, combining with our theory of what a fish is).[12] When we learn that a whale is not a fish, we are recognizing that whales don't in fact fit the theory we had about what makes something a fish. Theory-theory also postulates that people's theories about the world are what inform their conceptual knowledge of the world. Therefore, analysing people's theories can offer insights into their concepts. In this sense, "theory" means an individual's mental explanation rather than scientific fact. This theory criticizes classical and prototype theory as relying too much on similarities and using them as a sufficient constraint. It suggests that theories or mental understandings contribute more to what has membership to a group rather than weighted similarities, and a cohesive category is formed more by what makes sense to the perceiver. Weights assigned to features have shown to fluctuate and vary depending on context and experimental task demonstrated by Tversky. For this reason, similarities between members may be collateral rather than causal.[16]

Ideasthesia

According to the theory of ideasthesia (or "sensing concepts"), activation of a concept may be the main mechanism responsible for creation of phenomenal experiences. Therefore, understanding how the brain processes concepts may be central to solving the mystery of how conscious experiences (or qualia) emerge within a physical system e.g., the sourness of the sour taste of lemon.[17] This question is also known as the hard problem of consciousness.[18][19] Research on ideasthesia emerged from research on synesthesia where it was noted that a synesthetic experience requires first an activation of a concept of the inducer.[20] Later research expanded these results into everyday perception.[21]

There is a lot of discussion on the most effective theory in concepts. Another theory is semantic pointers, which use perceptual and motor representations and these representations are like symbols.[22]

Etymology

The term "concept" is traced back to 1554–60 (Latin conceptum – "something conceived").[23]

See also

- Abstraction

- Categorization

- Class (philosophy)

- Concept and object

- Concept map

- Conceptual blending

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual history

- Conceptual model

- Conversation theory

- Definitionism

- Formal concept analysis

- Fuzzy concept

- Hypostatic abstraction

- Idea

- Ideasthesia

- Noesis

- Notion (philosophy)

- Object (philosophy)

- Process of concept formation

- Schema (Kant)

References

- Chapter 1 of Laurence and Margolis' book called Concepts: Core Readings. ISBN 9780262631938

- Carey, S. (1991). Knowledge Acquisition: Enrichment or Conceptual Change? In S. Carey and R. Gelman (Eds.), The Epigenesis of Mind: Essays on Biology and Cognition (pp. 257-291). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- https://bcs.mit.edu/research/cognitive-science

- Eric Margolis; Stephen Lawrence. "Concepts". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab at Stanford University. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- Eysenck. M. W., (2012) Fundamentals of Cognition (2nd) Psychology Taylor & Francis.

- Margolis, Eric; Laurence, Stephen (2007). "The Ontology of Concepts—Abstract Objects or Mental Representations?". Nous. 41 (4): 561–593. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.188.9995. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0068.2007.00663.x.

- Jerry Fodor, Concepts: Where Cognitive Science Went Wrong

- Carey, Susan (2009). The Origin of Concepts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536763-8.

- Murphy, Gregory (2002). The Big Book of Concepts. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ISBN 978-0-262-13409-5.

- McCarthy, Gabby (2018) "Introduction to Metaphysics". pg. 35

- Eysenck. M. W., (2012) Fundamentals of Cognition (2nd) Psychology Taylor & Francis

- Stephen Lawrence; Eric Margolis (1999). Concepts and Cognitive Science. in Concepts: Core Readings: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 3–83. ISBN 978-0-262-13353-1.

- 'Godel's Rationalism', Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Brown, Roger (1978). A New Paradigm of Reference. Academic Press Inc. pp. 159–166. ISBN 978-0-12-497750-1.

- TAYLOR, John R. (1989). Linguistic Categorization: Prototypes In Linguistic Theory.

- Murphy, Gregory L.; Medin, Douglas L. (1985). "The role of theories in conceptual coherence". Psychological Review. 92 (3): 289–316. doi:10.1037//0033-295x.92.3.289. ISSN 0033-295X. PMID 4023146.

- Mroczko-Wąsowicz, A., Nikolić D. (2014) Semantic mechanisms may be responsible for developing synesthesia. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8:509. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00509

- Stevan Harnad (1995). Why and How We Are Not Zombies. Journal of Consciousness Studies 1: 164–167.

- David Chalmers (1995). Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2 (3): 200–219.

- Nikolić, D. (2009) Is synaesthesia actually ideaesthesia? An inquiry into the nature of the phenomenon. Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Synaesthesia, Science & Art, Granada, Spain, April 26–29, 2009.

- Gómez Milán, E., Iborra, O., de Córdoba, M.J., Juárez-Ramos V., Rodríguez Artacho, M.A., Rubio, J.L. (2013) The Kiki-Bouba effect: A case of personification and ideaesthesia. The Journal of Consciousness Studies. 20(1–2): pp. 84–102.

- Blouw, P., Solodkin, E., Thagard, P., & Eliasmith, C. (2016). Concepts as semantic pointers: A framework and computational model. Cognitive Science, 40(5), 1128–1162. doi:10.1111/cogs.12265

- "Homework Help and Textbook Solutions | bartleby". Archived from the original on 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2011-11-25.The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition.

Further reading

- Armstrong, S. L., Gleitman, L. R., & Gleitman, H. (1999). what some concepts might not be. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, Concepts (pp. 225–261). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Carey, S. (1999). knowledge acquisition: enrichment or conceptual change? In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 459–489). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Fodor, J. A., Garrett, M. F., Walker, E. C., & Parkes, C. H. (1999). against definitions. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 491–513). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Fodor, Jerry; Lepore, Ernest (1996). "The red herring and the pet fish: Why concepts still can't be prototypes". Cognition. 58 (2): 253–270. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(95)00694-X. PMID 8820389. S2CID 15356470.

- Hume, D. (1739). book one part one: of the understanding of ideas, their origin, composition, connexion, abstraction etc. In D. Hume, a treatise of human nature. England.

- Murphy, G. (2004). Chapter 2. In G. Murphy, a big book of concepts (pp. 11 – 41). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Murphy, G., & Medin, D. (1999). the role of theories in conceptual coherence. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 425–459). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Prinz, Jesse J. (2002). Furnishing the Mind. doi:10.7551/mitpress/3169.001.0001. ISBN 9780262281935.

- Putnam, H. (1999). is semantics possible? In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 177–189). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Quine, W. (1999). two dogmas of empiricism. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 153–171). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Rey, G. (1999). Concepts and Stereotypes. In E. Margolis, & S. Laurence (Eds.), Concepts: Core Readings (pp. 279–301). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Rosch, E. (1977). Classification of real-world objects: Origins and representations in cognition. In P. Johnson-Laird, & P. Wason, Thinking: Readings in Cognitive Science (pp. 212–223). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rosch, E. (1999). Principles of Categorization. In E. Margolis, & S. Laurence (Eds.), Concepts: Core Readings (pp. 189–206). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Schneider, Susan (2011). "Concepts: A Pragmatist Theory". The Language of Thought. pp. 159–182. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9780262015578.003.0071. ISBN 9780262015578.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1999). philosophical investigations: sections 65–78. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 171–175). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- The History of Calculus and its Conceptual Development, Carl Benjamin Boyer, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60509-4

- The Writings of William James, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-39188-4

- Logic, Immanuel Kant, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-25650-2

- A System of Logic, John Stuart Mill, University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 1-4102-0252-6

- Parerga and Paralipomena, Arthur Schopenhauer, Volume I, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-824508-4

- Kant's Metaphysic of Experience, H. J. Paton, London: Allen & Unwin, 1936

- Conceptual Integration Networks. Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner, 1998. Cognitive Science. Volume 22, number 2 (April–June 1998), pp. 133–187.

- The Portable Nietzsche, Penguin Books, 1982, ISBN 0-14-015062-5

- Stephen Laurence and Eric Margolis "Concepts and Cognitive Science". In Concepts: Core Readings, MIT Press pp. 3–81, 1999.

- Hjørland, Birger (2009). "Concept theory". Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 60 (8): 1519–1536. doi:10.1002/asi.21082.

- Georgij Yu. Somov (2010). Concepts and Senses in Visual Art: Through the example of analysis of some works by Bruegel the Elder. Semiotica 182 (1/4), 475–506.

- Daltrozzo J, Vion-Dury J, Schön D. (2010). Music and Concepts. Horizons in Neuroscience Research 4: 157–167.

External links

| Look up concept in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Concept. |

- Concept at PhilPapers

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Concepts". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Concept at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- "Concept". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Theory–Theory of Concepts". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Classical Theory of Concepts". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Blending and Conceptual Integration

- Conceptual Science and Mathematical Permutations

- Concept Mobiles Latest concepts

- v:Conceptualize: A Wikiversity Learning Project

- Concept simultaneously translated in several languages and meanings

- TED-Ed Lesson on ideasthesia (sensing concepts)