De facto embassy

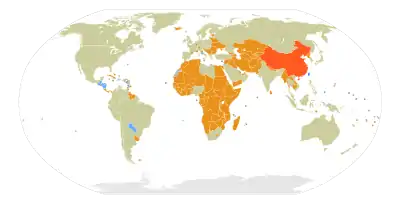

A de facto embassy is an office or organisation that serves de facto as an embassy in the absence of normal or official diplomatic relations among countries, usually to represent nations which lack full diplomatic recognition, regions or dependencies of countries, or territories over which sovereignty is disputed. In some cases, diplomatic immunity and extraterritoriality may be granted.[1]

Alternatively, states which have broken off direct bilateral ties will be represented by an "interests section" of another embassy, belonging to a third country that has agreed to serve as a protecting power and is recognised by both states. When relations are exceptionally tense, such as during a war, the interests section is staffed by diplomats from the protecting power. For example, when Iraq and the U.S. broke diplomatic relations due to the Gulf War, Poland became the protecting power for the United States. The United States Interests Section of the Polish Embassy in Iraq was headed by a Polish diplomat.[2] However, if the host country agrees, an interests section may be staffed by diplomats from the sending country. From 1977 to 2015, the United States Interests Section in Havana was staffed by Americans, even though it was formally a section of the Swiss Embassy to Cuba.

Taiwan

Foreign missions in Taiwan

Many countries maintain formal diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China but operate unofficial "trade missions" or "representative offices" in Taipei to deal with Taiwan-related commercial and consular issues. Often, these delegations may forward visa applications to their nearest embassy or consulate rather than processing them locally.[3]

When the United States ended diplomatic relations with Taipei in 1979, it established a non-governmental body known as the American Institute in Taiwan, to serve its interests on the island. By contrast, other countries were represented by privately operated bodies; the United Kingdom was informally represented by the "Anglo-Taiwan Trade Committee", while France was similarly represented by a "Trade Office".[4]

These were later renamed the "British Trade and Cultural Office" and "French Institute" respectively, and, were headed by career diplomats on secondment, rather than being operated by chambers of commerce or trade departments.[4]

France now maintains a "French Office in Taipei", with cultural, consular and economic sections,[5] while the "British Office"[6] and German Institute Taipei[7] perform similar functions on behalf of the United Kingdom and Germany.

Other countries which have broken off diplomatic relations with Taiwan also established de facto missions. In 1972, Japan established the "Interchange Association, Japan" (renamed the "Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association" in 2017),[8] headed by personnel "on leave" from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[9] This became known as the "Japanese formula", and would be adopted by other countries like the Philippines in 1975, which established the "Asian Exchange Center", replacing its former Embassy.[10] This was renamed the "Manila Economic and Cultural Office" in 1989.[11]

Australia ended formal diplomatic relations in 1972, but did not establish an "Australian Commerce and Industry Office" until 1981.[12] This was under control of the Australian Chamber of Commerce.[13] It was renamed the "Australian Office in Taipei" in 2012.[14] By contrast, New Zealand, which also ended formal diplomatic relations in 1972, did not establish the "New Zealand Commerce and Industry Office" in Taipei until 1989.[15]

South Korea, which broke off diplomatic relations in 1992, has been represented by the "Korean Mission in Taipei" since 1993.[16] South Africa, which ended diplomatic ties in 1998, is represented by the "Liaison Office of the Republic of South Africa".[17]

India, which has always had diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China, established an "India–Taipei Association" in 1995, which is also authorised to provide consular and passport services.[18]

Singapore, despite its close ties with Taiwan, did not establish formal diplomatic relations, although it was the last ASEAN country to establish diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China, in 1990.[19] Consequently, it only established a "Trade Representative Office" in Taipei in 1979, which was renamed the "Singapore Trade Office in Taipei" in 1990.[20]

Taiwan missions in other countries

Similarly, Taiwan maintains "representative offices" in other countries, which handle visa applications as well as relations with local authorities.[21] These establishments use the term "Taipei" instead of "Taiwan" or "Republic of China" since the term "Taipei" avoids implying that Taiwan is a separate country from China or that there are "Two Chinas", both of which would cause difficulties for their host countries.

In 2007, for example, the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs, Dermot Ahern, confirmed that Ireland recognised the Government of the People's Republic of China as the sole legitimate government of China, and that while the Taipei Representative Office in Dublin had a representative function in relation to economic and cultural promotion, it had no diplomatic or political status.[22]

Before the 1990s, the names of these offices would vary considerably from country to country. For example, in the United States, Taipei's mission was known as the "Coordination Council for North American Affairs" (CCNAA),[23] in Japan as the "Association of East Asian Relations" (AEAR),[10] in the Philippines as the "Pacific Economic and Cultural Center"[10] and in the United Kingdom as the "Free Chinese Centre".[24]

However, in May 1992, the AEAR offices in Japan became Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Offices,[25] as did the "Free Chinese Centre" in London.[26] In September 1994, the Clinton Administration announced that the CCNAA office in Washington could similarly be called the Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office.[27]

Earlier in 1989, the "Pacific Economic and Cultural Center" in Manila became the "Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in the Philippines".[11] In 1991, the "Taiwan Marketing Service" office in Canberra, Australia, established in 1988, also became a "Taipei Economic and Cultural Office", along with the "Far East Trading Company" offices in Sydney and Melbourne.[28]

Other names are still used elsewhere; for example, the mission in Moscow is formally known as the "Representative Office in Moscow for the Taipei–Moscow Economic and Cultural Coordination Commission",[29] the mission in New Delhi is known as the "Taipei Economic and Cultural Center".[30] while the mission in Pretoria is known as the "Taipei Liaison Office".[31]

In Papua New Guinea and Fiji, the local missions are known as the "Trade Mission of the Republic of China (Taiwan) in Papua New Guinea"[32] and "Trade Mission of the Republic of China (Taiwan) to the Republic of Fiji"[33] respectively, despite both countries having diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China. The Taipei Representative Office in Singapore was similarly known as the "Trade Mission of the Republic of China" until 1990.[20]

In addition, Taiwan maintains "Taipei Economic and Cultural Offices" in Hong Kong and Macau, both Special Administrative Regions of the People's Republic of China. Previously, Taiwan was represented in Hong Kong by the "Chung Hwa Travel Service", established in 1966.[34] In Macau it was represented by the "Taipei Trade and Tourism Office", established in 1989, renamed the "Taipei Trade and Cultural Office" in 1999.[35]

In May 2011, the "Chung Hwa Travel Service" was renamed the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Hong Kong, and in May 2012, the "Taipei Trade and Cultural Office" became the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Macau.[36]

Relations between Taiwan and China are conducted through two quasi-official organisations, the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF) in Taipei, and the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS) in Beijing.[37] In 2012, the two organisations' chairmen, Lin Join-sane and Chen Yunlin announced talks on opening reciprocal representative offices, but did not commit to a timetable or reach an agreement.[38]

In 2013, President Ma Ying-jeou outlined plans to establish three SEF representative offices in China, with the ARATS establishing representative offices in Taiwan.[39] The opposition Democratic Progressive Party expressed fears that China could use the offices as a channel for intelligence gathering in Taiwan, while China expressed concerns that they could be used as possible gathering areas for student demonstrators.[40]

Disputed territories

Northern Cyprus

As the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, declared in 1983, is only recognised as an independent state by Turkey, it is represented in other countries by "Representative Offices", most notably in London, Washington, New York, Brussels, Islamabad, Abu Dhabi and Baku.[41]

West Germany and East Germany

Prior to the reunification of Germany, West and East Germany were each represented by a "permanent mission" (Ständige Vertretung),[42] in East Berlin and Bonn respectively. These were headed by a "permanent representative", who served as a de facto ambassador.[43] The permanent missions were established under Article 8 of the Basic Treaty in 1972.[44]

Previously, West Germany had always claimed to represent the whole of Germany, reflected in the Hallstein Doctrine, which prescribed that the Federal Republic would not establish or maintain diplomatic relations with any state that recognised the GDR.[45] This opposition even extended to East Germany being allowed to open trade missions in countries such as India, which Bonn viewed as de facto recognition of the government in East Berlin.[46]

However, the GDR operated unofficial missions in Western countries, such as Britain, where "KfA Ltd", an agency of the Kammer für Außenhandel, or Department of Foreign Trade of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was established in 1959.[47] By the early 1970s, this had begun to function as a de facto East German embassy in London, including diplomats on its staff.[48]

Although after 1973, West Germany no longer asserted an exclusive mandate over the whole of Germany, it did not consider East Germany to be a "foreign" country. Instead of being conducted through the Foreign Office, relations were conducted through a separate Federal Ministry for Intra-German Relations, known until 1969 as the Federal Ministry of All-German Affairs.[49]

By contrast, East Germany did consider West Germany a completely separate country, meaning that while the East German mission in Bonn was accredited to the West German Chancellery, its West German counterpart in East Berlin was accredited to East Germany's Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[50]

Rhodesia after UDI

Following its Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965, Rhodesia maintained overseas missions in Lisbon and Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) until 1975[51] and an "Accredited Diplomatic Representative" in Pretoria.[52] The Rhodesian Information Office in Washington remained open, but its director, Ken Towsey, and his staff were deprived of their diplomatic status.[53] (Following the country's independence as Zimbabwe, Towsey became chargé d'affaires at the new Embassy.)[54]

.svg.png.webp)

The High Commission in London, known as Rhodesia House, continued to function until it was closed in 1969, following the decision by white Rhodesians in a referendum to make the country a republic, along with the British Residual Mission in Salisbury.[56] Prior to its closure, the mission flew the newly adopted Flag of Rhodesia in a provocative gesture, as the Commonwealth Prime Ministers arrived in London for their Conference.[57] This was considered illegal by the Foreign Office, and prompted calls by Labour MP Willie Hamilton, who condemned it as "the flag of an illegal Government in rebellion against the Crown", for its removal.[55]

In Australia, the federal government in Canberra sought to close the Rhodesian Information Centre in Sydney.[58] However, it remained open, operating under the jurisdiction of the state of New South Wales.[59] In 1973, the Labor government of Gough Whitlam cut post and telephone links to the Centre, but this was ruled illegal by the High Court.[60] An office was also established in Paris, but this was closed down by the French government in 1977.[61]

Similarly, the United States recalled its consul-general from Salisbury, and reduced consular staff,[62] but did not move to close its consulate until the declaration of a republic in 1970.[63] South Africa, however, retained its "Accredited Diplomatic Representative" after UDI,[64] which allowed it to continue to recognise British sovereignty as well as to deal with the de facto authority of the government of Ian Smith.[65]

The self-styled "South African Diplomatic Mission" in Salisbury became the only such mission remaining in the country after 1975,[66] when Portugal downgraded its mission to consul level,[67] having recalled its consul-general in Salisbury in May 1970.[68]

Bophuthatswana

Bophuthatswana, one of four nominally independent "homelands" created by South Africa under apartheid, was not recognised as an independent state by any other country.[69] Consequently, it only had diplomatic relations with Pretoria, which maintained an embassy in Mmabatho, its capital.[70] However, it established representative offices internationally, including London[71] and Tel Aviv.[72]

.svg.png.webp)

The opening of "Bophuthatswana House" in Holland Park in London in 1982, attended by the homeland's President, Lucas Mangope, prompted demonstrations by the Anti-Apartheid Movement, and while the British government gave Mangope a special travel document to enter the United Kingdom, it refused to accord the mission diplomatic status.[73]

In 1985, a "Bophuthatswana House" was opened in Tel Aviv, in a building on HaYarkon Street next to the British Embassy.[74] Despite the objections of the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the homeland's flag was flown from the building.[75]

Following the end of apartheid and the reincorporation of the homeland into South Africa, the Bophuthatswana government properties were acquired by the new South African government and sold.[76]

China in Hong Kong and Macau

When Hong Kong was under British administration, China did not establish a consulate in what it considered to be part of its national territory.[77] However, the Communist government of the People's Republic of China in Beijing, and its predecessor, the Kuomintang government of the Republic of China in Nanjing established de facto representation in the colony.

While the Nationalist government had negotiated with the British regarding the appointment of a Consul-General in Hong Kong in 1945, it decided against such an appointment, with its representative in the colony, T W Kwok (Kuo Teh-hua) instead being styled "Special Commissioner for Hong Kong".[78] This was in addition to his role as Nanjing's Special Commissioner for Guangdong and Guangxi.[79] Disagreements also arose with the British authorities, with the Governor, Alexander Grantham, opposing an office building for the "Commissioner for Foreign Affairs of the Provinces of Kwantung and Kuangsi" being erected on the site of the Walled City in Kowloon.[80] In 1950, following British recognition of the People's Republic of China, the office of the Special Commissioner was closed and Kwok withdrawn.[81]

In 1956, the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai requested the opening of a representative office in Hong Kong, but this also was opposed by Grantham, who advised the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Alan Lennox-Boyd in 1957 that it would a) give "an aura of respectability" to pro-Communist elements, b) have "a deplorable effect" on the morale of Chinese in Hong Kong, c) give the impression to friendly countries that Britain was retreating from the colony, d) that there would be no end to the claims of the Chinese representative as to what constituted his functions, and e) become a target for Kuomintang and other anti-communist activities.[82]

Consequently, the People's Republic of China was only represented unofficially in Hong Kong by the Xinhua News Agency Hong Kong Branch, which had been operating in the colony since 1945.[83] In addition to being a bona fide news agency, Xinhua also served as cover for the "underground" local branch of the Chinese Communist Party[84] known as the Hong Kong and Macau Work Committee (HKMWC).[85] It also opened additional district branches on Hong Kong Island, Kowloon and the New Territories in 1985 to expand its influence.[86]

Despite its unofficial status, the directors of the Xinhua Hong Kong Branch included high-ranking former diplomats such as Zhou Nan, former Ambassador to the United Nations and Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs, who later negotiated the Sino-British Joint Declaration on the future of Hong Kong.[87] His predecessor, Xu Jiatun, was also vice-chairman of the Hong Kong Basic Law Drafting Committee, before fleeing to the United States in response to the military crackdown on the Tiananmen Square protests, where he went into exile.[88]

On 18 January 2000, after the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong, the branch office of Xinhua became the Liaison Office of the Central People's Government in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.[89]

When Macau was under Portuguese administration, the People's Republic of China was unofficially represented by the Nanguang trading company.[90] This later became known as China Central Enterprise Nam Kwong (Group).[91] Established in 1949, officially to promote trade ties between Macau and mainland China, it operated as the unofficial representative and "shadow government" of the People's Republic in relation to the Portuguese administration.[92]

It also served to challenge the rival "Special Commissariat of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China" in the territory, which represented the Kuomintang government on Taiwan.[92] This was closed after the pro-Communist 12-3 incident in 1966, after which the Portuguese authorities agreed to ban all Kuomintang activities in Macau.[93] Following the Carnation Revolution, Portugal redefined Macau as a "Chinese territory under Portuguese administration" in 1976.[94] However, Lisbon did not establish diplomatic relations with Beijing until 1979.[95]

In 1984, Nam Kwong was split into political and trading arms.[96] On 21 September 1987, a Macau branch of Xinhua News Agency was established which, as in Hong Kong, became Beijing's unofficial representative, replacing Nam Kwong.[97] On 18 January 2000, a month after the transfer of sovereignty over Macau, the Macau branch became the Liaison Office of the Central People's Government in the Macau Special Administrative Region.[98]

Regions

Hong Kong

Due to Hong Kong's status as a Special Administrative Region, foreign diplomatic missions there function independently of their embassies in Beijing, reporting directly to their foreign ministries.[99][100] For example, the United States Consulate General reports to the Department of State with the Consul General as the "Chief of Mission".[101]

Similarly, Hong Kong Economic and Trade Offices enjoy some privileges and immunities equivalent to those of a diplomatic mission under legislation passed by host countries such as the United Kingdom,[102] Canada[103] and Australia.[104] Under British administration, they were known as Hong Kong Government Offices, and were headed by a Commissioner.[105][106]

When Hong Kong was under British administration, diplomatic missions of Commonwealth countries, such as Australia,[107] Bangladesh[108] Canada,[109] India,[110] Malaysia,[111] New Zealand[112] Nigeria[113] and Singapore[114] maintained Commissions. However, the Australian Commission was renamed the Consulate-General in 1986.[115] Following the transfer of sovereignty to China in 1997, the remaining Commissions were renamed Consulates-General.[116] with the last Commissioner becoming Consul-General.[117]

Macao

Macao as a Special Administrative Region, It has the right to set up different offices in many places around the world. Similarly, Macao Economic and Trade Offices enjoy some privileges and immunities equivalent to those of a diplomatic mission under legislation passed by host countries such as Portugal, Belgium and so on.

Montenegro

Prior to achieving full independence in 2006, Montenegro effectively ran its own foreign policy independently of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Union of Serbia and Montenegro, with a Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Podgorica and trade missions abroad operating as de facto embassies.[118]

Dependent territories

Commonwealth of Nations

Historically, in British colonies, independent Commonwealth countries were represented by Commissions, which functioned independently of their High Commissions in London. For example, Canada,[119] Australia[120] and New Zealand[121] maintained Commissions in Singapore, while following its independence in 1947, India established Commissions in Kenya,[122] Trinidad and Tobago,[123] and Mauritius[124] which became High Commissions on independence. Canada formerly had a Commissioner to Bermuda, although this post was held by the Consul-General to New York City,[125][126] but there is now an Honorary Canadian Consulate on the island.[127]

Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia, uniquely among British colonies, was represented in London by a High Commission from 1923, while the British government was represented by a High Commission in Salisbury from 1951.[128] Following the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965, when the British High Commissioner was withdrawn[129] and the Rhodesian High Commissioner requested to leave London, both High Commissions were downgraded to residual missions before being closed down in 1970.[130]

The self-governing colony also established a High Commission in Pretoria, following the decision of the then Union of South Africa to establish one in Salisbury, which, after South Africa's withdrawal from the Commonwealth in 1961, was renamed the "South African Diplomatic Mission" with the High Commissioner becoming the "Accredited Diplomatic Representative".[128] Southern Rhodesia, which briefly became part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, was also able to establish its own consulate in Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) in Mozambique.[131] In addition, it also had a "Minister for Rhodesian Affairs" in Washington, DC operating under the aegis of the British Embassy,[132] as well representatives in Tokyo and Bonn.[133]

During 1965, the government of Rhodesia, as the colony now called itself, made moves to establish a mission in Lisbon separate from the British Embassy, with its own accredited representative, prompting protests from the British government, which was determined that the representative, Harry Reedman, should be a nominal member of the British Ambassador's staff.[134] For their part, the Portuguese authorities sought a compromise whereby they would accept Reedman as an independent representative but deny him diplomatic status.[135]

Trade missions

South Africa and neighbouring countries

Under apartheid, South Africa maintained trade missions in neighbouring countries, with which it did not have diplomatic relations, such as Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe),[136] where, following the country's independence, the "South African Diplomatic Mission" in Salisbury (now Harare) was closed.[137] A trade mission was also established in Maputo, Mozambique,[138] in 1984, nine years after the South African consulate was closed following independence in 1975.[139]

Similarly, Mauritius maintained a trade mission in Johannesburg, the country's commercial capital,[140] as did Zimbabwe, after the closure of its missions in Pretoria and Cape Town.[141]

Following majority rule in 1994, full diplomatic relations were established, and these became High Commissions, after South Africa rejoined the Commonwealth.[142]

South Korea and China

Prior to the establishment of full diplomatic relations in 1992, South Korea and the People's Republic of China established trade offices in Beijing and Seoul, under the auspices of the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade, and KOTRA, the Korea Trade Promotion Corporation respectively.[143] The South Korean office in Beijing was established in January 1991, while the Chinese office was established in April of that year.[144]

Other missions

South Africa and China

Prior to the establishment of full diplomatic relations in 1998, South Africa and the People's Republic of China established "cultural centres" in Beijing and Pretoria, known as the South African Centre for Chinese Studies and the Chinese Centre for South African Studies respectively.[145] Although the Centres, each headed by a Director, did not use diplomatic titles, national flags, or coats of arms, their staff used diplomatic passports and were issued with diplomatic identity documents, while their vehicles had diplomatic number plates.[146] They also performed visa and consular services.[147]

Israel and China

Prior to the establishment of full diplomatic relations in 1992, Israel and the People's Republic of China established representative offices in Beijing and Tel Aviv. The Israeli office was formally known as the Liaison Office of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities.[148] This was opened in June 1990.[149] China was similarly represented by a branch of the China International Travel Service, which also opened in 1990.[150]

Liaison Offices

Greece and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

Until 2019, Greece and the then Republic of Macedonia only maintained "Liaison Offices", with Greece being represented in Skopje by a mission known as the "Liaison Office of the Hellenic Republic",[151] and Macedonia by the "Liaison Office of the Republic of Macedonia" in Athens.[152] This was to the naming dispute between the two states, but following the Republic of Macedonia adoption of the name "North Macedonia" and the signing of an agreement with Greece, the two countries' diplomatic missions were upgraded to embassies, with Greece's representation in Bitola and North Macedonia's representation in Thessaloniki being upgraded to Consulates-General.[153]

Vietnam and the United States

In January 1995, Vietnam and the United States established "Liaison Offices" in Washington and Hanoi, the first such representation in the two countries since the end of the Vietnam War, when the US-backed South Vietnam fell to the Communist-controlled North.[154] On 11 July, President Bill Clinton announced the normalisation of relations between the two countries, and the following month, both countries upgraded their Liaison Offices to Embassy status, with the United States later opening a consulate general in Ho Chi Minh City, while Vietnam opened a consulate in San Francisco, California.[155]

China and the United States

Following President Richard Nixon's visit to China, the United States and the People's Republic of China agreed to open "Liaison Offices" in Washington and Beijing in 1973, described by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger as "embassies in all but name".[156]

Although the Embassy of the Republic of China on Taiwan remained, it increasingly became overshadowed by the "Liaison Office of the People's Republic of China",[157] which, under Executive Order 11771, was accorded the same privileges and immunities enjoyed by the diplomatic missions accredited to the United States.[158]

George H.W. Bush, later Vice-President under Ronald Reagan and President between 1989 and 1993, served as Chief of the "United States Liaison Office" between 1974 and 1975.[159] The last holder of the post was Leonard Woodcock, formerly president of the United Auto Workers, who became the first Ambassador when full diplomatic relations were established in 1979.[160]

North Korea and South Korea

The joint Inter-Korean Liaison Office was established as part of Panmunjom Declaration signed by North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and South Korean President Moon Jae-in on April 27, 2018, during the 2018 inter-Korean Summit in Panmunjom. The joint liaison office provided direct communication channel for the two Koreas.[161] The office was bombed by the DPRK at 2:50 PM local time on 16 June 2020.[162]

Interests sections

When two nations break diplomatic relations, their embassies are turned over to neutral countries that act as protecting powers. The protecting power is responsible for all diplomatic communications on behalf of the protected power. When the situation improves, the feuding countries may be willing to accept diplomats from the other country on an unofficial basis. The original embassy is known as an interests section of the protecting power. For example, until 2015 the Cuban Interests Section was staffed by Cubans and located in the old Cuban Embassy in Washington, but it was officially an interests section of the Swiss Embassy to the United States.[165]

See also

References

- New Taiwan-U.S. diplomatic immunity pact a positive move: scholar, Focus Taiwan, 12 February 2013

- Former Polish Director of U.S. Interests Section in Baghdad Krzysztof Bernacki Receives the Secretary's Award for Distinguished Service, Department of State, 28 February 2003

- De facto embassies in Taipei folding the flag, Asia Times, 14 June 2011

- Privatising the State, Béatrice Hibou, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2004, pages 157–158

- La France à Taiwan

- British Office

- "German Institute Taipei". Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Chang, Mao-sen (29 December 2016). "Foreign ministry supports name change". Taipei Times. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- The International Energy Relations of China, Kim Woodard Stanford University Press, 1980, page 125

- International Law of Recognition and the Status of the Republic of China, Hungdah Chiu, in The United States and the Republic of China: Democratic Friends, Strategic Allies, and Economic Partners, Steven W. Mosher Transaction Publishers, 1992, page 24

- Ensuring Interests: Dynamics of China-Taiwan Relations and Southeast Asia, Khai Leong Ho, Guozhong He, Institute of China Studies, University of Malaya, 2006, page 25

- The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate: 1962–1983, Ann Millar, UNSW Press, 2000, page 244

- Prospects for Australian Seafood Exports: A Case Study of the Taiwanese Market, Malcolm Tull Asia Research Centre on Social, Political, and Economic Change, Murdoch University, 1993, page 10

- Australian office renamed, Taipei Times, 30 May 2012

- Republic of China Yearbook Taiwan, Kwang Hwa Publishing Company, 1989, page 227

- Seoul tries to mend Taipei tie Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Taiwan Today, 8 November 1996

- Liaison Office of the Republic of South Africa

- "About Us – India-Taipei Association". Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Contemporary Southeast Asia, Volumes 7–8, Singapore University Press, 1985, page 215

- American Journal of Chinese Studies, Volumes 3–4, American Association for Chinese Studies, 1996, page 170

- Visa Requirements for the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan Archived 8 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Taipei Representative Office in the U.K., 1 July 2011

- Written Answers – Diplomatic Relations. Thursday, 8 February 2007 Dáil Éireann (Ref No: 3911/07)

- Memorandum of Understanding between the American Institute in Taiwan and the Coordination Council for North American Affairs on the Exchange of Information Concerning Commodity Futures and Options Matters, Signed at Arlington, Virginia this 11th day of January 1993

- The Cold War's Odd Couple: The Unintended Partnership Between the Republic of China and the UK, 1950–1958, Steven Tsang, I.B.Tauris, 2006, page 39

- Republic of China Yearbook Kwang Hwa Publishing Company, 1998, 145

- Former diplomats to Great Britain remember Thatcher, The China Post, 10 April 2013

- Taiwan's Relations with Mainland China: A Tail Wagging Two Dogs, Chi Su Routledge, 2008, page 31

- Australia and China: Partners in Asia, Colin Mackerras, Macmillan Education, 1996, page 33

- Representative Office in Moscow for the Taipei–Moscow Economic and Cultural Coordination Commission

- MoU between India-Taipei Association (ITA) in Taipei and Taipei Economic and Cultural Center (TECC) in India on cooperation in the field of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Cabinet, 14 October 2015

- Taipei Liaison Office in the RSA

- Trade Mission of the Republic of China (Taiwan) in Papua New Guinea

- Trade Mission of the Republic of China to the Republic of Fiji

- Is name change a game changer?, Taipei Times, 17 July 2011

- Macao allows Taipei office to issue visas to Chinese, Taipei Times, 7 January 2002

- Macau representative office in Taiwan opens The China Post, 14 May 2012

- Human rights as identities: difference and discrimination in Taiwan's China policy, Shih Chih-Yu in Debating Human Rights: Critical Essays from the United States and Asia, Peter Van Ness (ed.), Routledge, 2003, page 153

- SEF, ARATS push for reciprocal rep offices, Taiwan Today, 17 October 2012

- Ma defends cross-strait offices proposal, Taipei Times, 24 April 2013

- PRC has qualms over representative offices: Ma The China Post, 19 May 2015

- The Making of Informal States: Statebuilding in Northern Cyprus and Transdniestria, Daria Isachenko, Palgrave Macmillan, page 163

- History of the Berlin Wall

- East-West German trade up 8 percent The Christian Science Monitor, 8 September 1982

- Uniting Germany: Documents and Debates, 1944–1993, Volker Gransow, Konrad Hugo Jarausch, Berghahn Books, page 23

- The Two Germanies: Rivals struggle for Germany's soul – As worries surface in Bonn about the influx from the East, there are anxieties across Europe about the likely economic and international effects, The Guardian, 15 September 1989

- Germany's Cold War: The Global Campaign to Isolate East Germany, 1949–1969, University of North Carolina Press, 2003, page 26

- Uneasy Allies : British–German Relations and European Integration Since 1945, Klaus Larres, Elizabeth Meehan, OUP Oxford, 2000, page 76–77

- Friendly Enemies: Britain and the GDR, 1949–1990, Stefan Berger, Norman LaPorte, Berghahn Books, 2010, page 13

- German Politics Today Geoffrey K. Roberts, Manchester University Press, 2000, page 46

- Germany Divided: From the Wall to Reunification, A. James McAdams Princeton University Press, 1994, page 107

- Rhodesians to quit Lisbon, Glasgow Herald, 1 May 1975, page 4

- Sanctions: The Case of Rhodesia, Harry R. Strack, Syracuse University Press, 1978, page 52

- Goldberg Back British Stand In U.N. Session,Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 13 November 1965

- Rhodesia's Lobbyist Back for Mugabe, The Washington Post, 26 June 1980

- M.P. calls for removal of Rhodesian flag in Strand, The Glasgow Herald, 4 January 1969, page 1

- Rhodesia, Hansard, HC Deb 24 June 1969 vol 785 cc1218-27

- SMITH SHOWS THE FLAG, Associated Press Archive, 6 January 1969

- Rhodesia Office Will Be Closed, The Age, 3 April 1972

- The Nationals: The Progressive, Country, and National Party in New South Wales 1919–2006, Paul Davey, Federation Press, 2006 page 223

- Africa Contemporary Record: Annual Survey and Documents, Volume 6, Colin Legum, Africana Publishing Company, 1974

- US Not Closing Rhodesian Office, The Lewiston Daily Sun, 27 August 1977, page 8

- US To Restrict Sales To Rhodesia, Reading Eagle, 12 December 1965

- The Superpowers and Africa: The Constraints of a Rivalry, 1960–1990, Zaki Laïdi University of Chicago Press, 1990, page 55

- Foreign Affairs for New States: Some Questions of Credentials, Peter John Boyce, University of Queensland Press, January 1977, page 13

- Confrontation and Accommodation in Southern Africa: The Limits of Independence, Kenneth W. Grundy, University of California Press, 1973, page 257

- Native Vs. Settler: Ethnic Conflict in Israel/Palestine, Northern Ireland, and South Africa, Thomas G. Mitchell Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, page 141

- Sanctions: The Case of Rhodesia, Harry R. Strack, Syracuse University Press, 1978, page 77

- Portugal Severs Key Link With Rhodesia, Sarasota Herald-Tribune, 27 April 1970

- Bophuthatswana, HC Deb, Hansard, 19 October 1988 vol 138 cc872-3

- South Africa Suppresses Coup In Homeland, Chicago Tribune, 11 February 1988

- Toytown image hid apartheid tyranny: As white right-wingers die at the hands of Bophuthatswana forces, Richard Dowden examines the racial purpose of the 'homeland', The Independent, 12 March 1994

- Apartheid's "Little Israel", Arianna Lissoni, in Apartheid Israel: The Politics of an Analogy, Sean Jacobs, Jon Soske, Haymarket Books, 2015

- 'Bophuthatswana House' protest, Anti-Apartheid Movement Archive

- Foreign Ministry opposed to Bophuthatswana office in Israel, Associated Press, 5 June 1985

- The Unspoken Alliance: Israel's Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa, Sasha Polakow-Suransky, Pantheon Books, New York, 2010, page 157.

- Inside File: A des. res. in Trafalgar Square, one proud owner, The Independent, 11 May 1994

- The Long History of United Front Activity in Hong Kong, Hong Kong Journal, Cindy Yik-yi Chu, July 2011

- Democracy shelved: Great Britain, China, and attempts at constitutional reform in Hong Kong, 1945–1952, Steve Yui-Sang Tsang, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 1988, page 28

- Hegemonies Compared: State Formation and Chinese School Politics in Postwar Singapore and Hong Kong, Ting-Hong Wong, Routledge Press, 2002, page 96

- Britain and China 1945–1950: Documents on British Policy Overseas, Series I, Volume 8, S.R. Ashton, G. Bennett, K. Hamilton, Routledge, 2013 page 129

- Via Ports: From Hong Kong to Hong Kong, Alexander Grantham, Hong Kong University Press, 2012, page 106

- Government and Politics, Steve Tsang, Hong Kong University Press, 1995, pages 276

- Hong Kong: China's Challenge, Michael B. Yahuda Psychology Press, 1996, pages 46–47

- China's Political Economy, Wang Gungwu, John Wong World Scientific, 1998, page 360

- Elections and Democracy in Greater China, Larry Diamond, Ramon H. Myers, OUP Oxford, 2001, page 228

- Public Governance in Asia and the Limits of Electoral Democracy, Brian Bridges, Lok-sang Ho, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2009, page 155

- 'Poet diplomat' Zhou Nan takes aim at Occupy Central, South China Morning Post, 16 June 2014

- China's ex-proxy in Hong Kong fired for 'betrayal', UPI, 22 February 1991

- In Watching Hong Kong, China Loses The Shades, The New York Times, 20 February 2000

- Portuguese behavior towards the political transition and the regional integration of Macau in the Pearl River Region, Moisés Silva Fernandes, in Macau and Its Neighbours in Transition, Rufino Ramos, José Rocha Dinis, D.Y.Yuan, Rex Wilson, University of Macau, Macau Foundation, 1997, page 48

- NAM KWONG (GROUP) COMPANY LIMITED, China Daily, 22 September 1988

- Macao in Sino-Portuguese Relations, Moisés Silva Fernandes, in Portuguese Studies Review, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2009, page 155

- Macao Locals Favor Portuguese Rule, Sam Cohen, The Observer in Sarasota Herald-Tribune, 2 June 1974, page 4H

- Lisbon Seen in 1999 Macao Shift, The New York Times, 8 January 1987

- Sino-Portugal relations, Xinhua 24 August 2004

- Naked Tropics: Essays on Empire and Other Rogues, Kenneth Maxwell, Psychology Press, 2003, page 280

- Asia Yearbook, Far Eastern Economic Review, 1988

- Renamed Xinhua becomes a new force in Hong Kong's politics, Taipei Times, 21 January 2000

- "Christopher J. Marut Appointed as Director of the Taipei Office of the American Institute in Taiwan" (Press release). American Institute in Taiwan. 8 May 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- "Inspection of The Canadian Consulate General Hong Kong". Archived from the original on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- "Chiefs of Mission". U.S. Department of State.

- The Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office Act 1996

- Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office Privileges and Immunities Order

- Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office (Privileges and Immunities) Regulations 1996

- Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office Bill, Hansard, 25 November 1996

- LETTER: Hong Kong's road to democracy, The Independent, 23 August 1995

- Australian Commission Office Requirements, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 August 1982

- Business Directory of Hong Kong, Current Publications Company, 1988, page 797

- 2 China Dissidents Granted Asylum, Fly to Vancouver, Los Angeles Times, 17 September 1992

- Indians in Limbo as 1997 Hand-over Date Draws Nearer, Inter Press Service, 12 February 1996

- Officials puzzled by Malaysian decision, New Straits Times, 3 July 1984

- NZer's credibility under fire in Hong Kong court, New Zealand Herald, 27 March 2006

- Asia, Inc: The Region's Business Magazine, Volume 4, Manager International Company, 1996

- Singapore Lure Stirs Crowds In Hong Kong, Chicago Tribune, 12 July 1989

- Australian Foreign Affairs Record, Volume 56, Issues 7-12, Australian Government Public Service, 1985, page 1153

- About the Consulate-General

- In the swing of things Archived 23 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Embassy Magazine, September 2010

- Montenegro and Serbia: disassociation, negotiation, resolution?, Philip Lyon in De Facto States: The Quest for Sovereignty Tozun Bahcheli, Barry Bartmann, Henry Srebrnik, Routledge, 2004, page 60

- Colonial Reports Report on Sarawak, Great Britain, Colonial Office 1961, page 7

- Losing the Blanket: Australia and the End of Britain's Empire, David Goldsworthy Melbourne University Publish, 2002, page 28

- External Affairs Review, Volume 6, New Zealand. Dept. of External Affairs 1956, page 41

- Indian Coffee: Bulletin of the Indian Coffee Board, Volume 21, Coffee Board, 1957, page 202

- Caribbean Studies, Volume 16, Institute of Caribbean Studies, University of Puerto Rico, 1977, page 22

- The Establishment and Cultivation of Modern Standard Hindi in Mauritius, Lutchmee Parsad Ramyead, Mahatma Gandhi Institute, 1985, page 86

- The Canadian Commission to Bermuda Archived 27 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Canada's One-Time Bermuda Diplomat Dies

- Embassies and consulates - Bermuda

- Diplomacy with a Difference: the Commonwealth Office of High Commissioner, 1880–2006, Lorna Lloyd, BRILL, 2007, page 240

- Sir John Johnston, The Daily Telegraph, 25 October 2005

- The United Nations, international law, and the Rhodesian independence crisis, Jericho Nkala, Clarendon Press, 1985, page 76

- John Arthur KINSEY, Esq., Consul-General for the Federation at Lourenco Marques, London Gazette, 5 June 1959

- Isolated States: A Comparative Analysis, Deon Geldenhuys, Cambridge University Press, 1990, page 62

- Collective Responses to Illegal Acts in International Law: United Nations Action in the Question of Southern Rhodesia, Vera Gowlland-Debbas, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. 1990

- Rhodesia's Man in Lisbon: Objective Said To Be Achieved, The Glasgow Herald, 22 September 1965. page 9

- International Diplomacy and Colonial Retreat, Kent Fedorowich, Martin Thomas Routledge, 2013, page 186

- Thousands Rampage Through Harare, Upset Over Machel's Death, Associated Press, 21 October 1986

- Salisbury whites queue up to flee, The Age, 8 July 1980

- Youths Attack South African Trade Mission, United Press International, 5 November 1986

- South Africa, 1987–1988, Department of Foreign Affairs, page 207

- Port Louis Journal; Land of Apartheid Befriends an Indian Ocean Isle, The New York Times, 28 December 1987

- Coming To Terms: Zimbabwe in the International Arena, Richard Schwartz I.B.Tauris, 2001, page 68

- Portfolio of South Africa, Portfolio Publications, 1999

- S. Korea, China Agree to Set Up Trade Offices : Asia: The diplomatic accord is another setback for Communist North Korea, an ally of Beijing., Los Angeles Times, 21 October 1990

- China and South Korea in a New Triangle, Emerging Patterns of East Asian Investment in China: From Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, Sumner J. La Croix M.E. Sharpe, 1995, page 215

- Interpreting Chinese Foreign Policy: The Micro-macro Linkage Approach, Quansheng Zhao Oxford University Press, 1996, page 68

- Establishing the SA Mission in the PRC, Embassy of the People's Republic of China, 31 March 2008

- Colour, Confusion and Concessions: The History of the Chinese in South Africa, Hong Kong University Press, 1996, page 424

- A China Diary: Towards the Establishment of China-Israel Diplomatic Relations, E. Zev Sufott, Frank Cass, 1997, page ix

- Israel Strengthening Representation in China, Associated Press, 9 January 1991

- IDSA News Review on East Asia, Volume 5, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, 1991, page 375

- F.Y.R.O.M. – Greece's Bilateral Relations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Greece

- Interview for IBNA of Darko Angelov, Head of the liaison office of Republic of Macedonia in Athens, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Macedonia, 29 October 2015

- Greece, North Macedonia open embassies after name deal, AP, May 31, 2019

- U.S., Vietnam to Establish Liaison Offices, The Washington Post, Thomas W. Lippman 28 January 1995

- Political Risk Yearbook: East Asia & the Pacific, PRS Group, 2008, page 27

- A Tangled Web: The Making of Foreign Policy in the Nixon Presidency, William P. Bundy, I.B.Tauris, 1998, page 402

- Chiang Ching-kuo's Leadership in the Development of the Republic of China on Taiwan, Shao Chuan Leng, University Press of America, 1993, page 137

- Executive Order 11771 – Extending Diplomatic Privileges and Immunities to the Liaison Office of the People's Republic of China in Washington, DC and to Members Thereof, RICHARD NIXON, The White House, 18 March 1974

- The China Diary of George H. W. Bush: The Making of a Global President, Jeffrey A. Engel, Princeton University Press, 2008

- Leonard Woodcock; President of United Auto Workers Union, Envoy to China, Los Angeles Times, 18 January 2001

- North and South Korea Open Full-Time Liaison Office at Border, The New York Times, September 14, 2018

- "Alert: South Korea says North Korea blew up an inter-Korean liaison office amid rising tensions between the rivals". SFChronicle.com. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- John Pike. "Chosen Soren". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "Stage set for Japan to seize North Korea's 'embassy' Archived October 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine." Agence France-Presse. June 18, 2007. Retrieved on January 15, 2009.

- Krauss, Clifford (12 February 1991). "Swiss to Sponsor Cuba's Diplomats". The New York Times.