Desert Inn

The Desert Inn, also known as the D.I., was a hotel and casino on the Las Vegas Strip in Paradise, Nevada, which operated from April 24, 1950, to August 28, 2000. Designed by architect Hugh Taylor and interior design by Jac Lessman, it was the fifth resort to open on the Strip, the first four being El Rancho Vegas, The New Frontier, the still-operating Flamingo, and the now-defunct El Rancho (then known as the Thunderbird). It was situated between Desert Inn Road and Sands Avenue.

| Desert Inn Hotel and Casino | |

|---|---|

| |

The Desert Inn in 1968 | |

| |

| Location | Paradise, Nevada, U.S. |

| Address | 3145 South Las Vegas Blvd |

| Opening date | April 24, 1950 |

| Closing date | August 28, 2000 |

| Theme | Desert |

| No. of rooms | 715 |

| Total gaming space | 35,000 sq ft (3,300 m2) |

| Signature attractions | Desert Inn Golf Course |

| Casino type | Land |

| Owner | 1964–1967 Moe Dalitz 1967–1988 Howard Hughes 1988–1993 Kirk Kerkorian 1993–1998 ITT / Sheraton Hotels and Resorts 1998–2000 Starwood 2000 Steve Wynn[1] |

| Previous names | Wilbur Clark's Desert Inn, Sheraton Desert Inn |

| Coordinates | 36°07′43″N 115°9′59″W |

The Desert Inn opened with 300 rooms and the Sky Room restaurant, headed by a chef formerly of the Ritz Paris, which once had the highest vantage point on the Las Vegas Strip. The casino, at 2,400 square feet (220 m2), was one of the largest in Nevada at the time. The nine-story St. Andrews Tower was completed during the first renovation in 1963, and the 14-story Augusta Tower became the Desert Inn's main tower when it was completed in 1978 along with the seven-story Wimbledon Tower. The Palms Tower was completed in 1997 with the second and final renovation. The Desert Inn was the first hotel in Las Vegas to feature a fountain at the entrance. In 1997, the Desert Inn underwent a $200 million renovation and expansion, but after it was purchased for $270 million by Steve Wynn in 2000, he decided to demolish it and build a new hotel and resort and casino. The remaining towers of the Desert Inn were imploded in 2004. Today, the Wynn and Encore are now where the Desert Inn once stood.

The original performance venue at the Desert Inn was the Painted Desert Room, later the Crystal Room, which opened in 1950 with 450 seats. Frank Sinatra made his Las Vegas debut there on September 13, 1951 and became a regular performer. The property included an 18-hole golf course which hosted the PGA Tour Tournament of Champions from 1953 to 1966. The golf course is now a part of the Wynn resort.[2]

History

The hotel was situated at 3145 Las Vegas Boulevard South, between Desert Inn Road and Sands Avenue.[3] The original name was Wilbur Clark's Desert Inn. Wilbur Clark, described by Frank Sinatra biographer James Kaplan as a "onetime San Diego bellhop and Reno craps dealer",[4] originally began building the resort with his brother in 1947 with $250,000, but ran out of money. Author Hal Rothman notes that "for nearly two years the framed structure sat in the hot desert sun, looking more like an ancient relic than a nascent casino".[5] Clark approached the Reconstruction Finance Corporation for investment, but it was struggling financially. In 1949, he met with Moe Dalitz, the head of the notorious Cleveland gang, the Mayfield Road Mob, and Dalitz agreed to fund 75% of the project with $1.3 million, and construction resumed.[5] Much of the financing came from the American National Insurance Company (ANICO),[6] though Clark became the public frontman of the resort while Dalitz remained quietly in the background as the principal owner. The resort would eventually be renamed Desert Inn and was called the "D.I." by Las Vegas locals and regular guests.[7]

The Desert Inn opened formally on April 24, 1950,[8][9] at a two-day gala which was heavily publicized nationally. Journalists from all of the major newspapers and magazines were invited, and the hotel paid $5,700 to cover air tickets. 150 invitations were sent out by Clark to VIPs with a credit limit of $10,000. About half the attendees at the opening were from California and Nevada. At the opening show in the Painted Desert Room were performers such as Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, Vivian Blaine, Pat Patrick, The Donn Arden Dancers, Van Heflin, Abbott and Costello, and the Desert Inn Orchestra, led by Ray Noble.[10] In attendance were a number of mafiosi, including Black Bill Tocco, Joe Massei, Sam Maceo, Peter Licavoli, and Frank Malone in a gala which Barbara Greenspun believed marked the beginning of heavy involvement of the mafia in the development of Las Vegas.[11] Sidney Korshak was one of its early investors.[11]

The Desert Inn became known for its "opulence" and top-notch service.[12] The first manager of the Desert Inn had previously worked as the manager at the Clift Hotel in San Francisco.[7] Lew and Edie Wasserman were frequent guests of the hotel.[13] During the 1950s, the hotel often hosted the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Winston Churchill, Adlai Stevenson, Senator John F. Kennedy, and former President Harry S. Truman.[12]

In the mid 1940s and early 1950s the city and its Chamber of Commerce worked to keep the Vegas nickname of the "Atomic City" going to attract tourists.[14][15][16] After the Desert Inn opened, so called "bomb parties" famously took place in the hotel's panoramic Sky Room, where patrons could view the detonations from a relatively safe distance while drinking Atomic Cocktails.[17][18]

In 1959, Lawrence Wien, owner of New York City's Plaza Hotel purchased the hotel, but signed a management deal for Clark to remain as manager.[19] In the early 1960s, the mafia-financed casino hotels of the Las Vegas Strip and Nevada came under close scrutiny by the FBI, and they placed increased pressure on the Nevada Gaming Control Board to force the mobsters out of Las Vegas. After Sam Giancana was spotted on the premises of Frank Sinatra's Cal Neva Lodge & Casino at Lake Tahoe, his gambling license was removed by the Board and he was forced to sell up and forfeit his share in the Sands Hotel and Casino.[20][21] The Desert Inn faced similar scrutiny by the FBI, attracting controversy at the same time for the involvement of Dalitz and his mobster associates,[22] but simultaneously called for the prosecution of the FBI for illegal wiretapping.[23] In 1964, Clark sold his remaining share in the hotel to Dalitz and business associates Morris Kleinman, Thomas McGinty and Sam Tucker. He died of a heart attack the following year. The bell captain of the Desert Inn, Jack Butler, remembered Clark: "Wilbur was the greatest guy. Without him this town never would've got off the ground. Everyone came into the club just to see him and he was all over the postcards. He was the only boss who would agree to have his picture taken".[24]

The Desert Inn's most famous guest, businessman Howard Hughes, arrived on Thanksgiving Day 1966, renting the hotel's entire top two floors.[25] After staying past his initial ten-day reservation, he was asked to leave in December so that the resort could accommodate the high rollers who were expected for New Year's Eve. Instead of leaving, Hughes started negotiations to buy the Desert Inn.[26] On March 27, 1967,[27] Hughes purchased the resort from Dalitz for $6.2 million in cash and $7 million in loans.[25] This was the first of many Las Vegas resort purchases by Hughes, including the Sands Hotel and Casino ($14.6 million) and the Frontier Hotel and Casino ($23 million).[26] However, Hughes refused to include the PGA Tour Tournament of Champions in the deal, so Dalitz moved the tournament to his Stardust Resort and Casino in 1967 and 1968.[28]

The reclusive Hughes continued to live in his penthouse suite at the Desert Inn for four years, never leaving his 250 square feet (23 m2) bedroom. Usually unclothed, he spent his time "negotiating purchases and business deals with the curtains drawn and windows and doors sealed shut with tape", and did not allow anyone from the hotel staff to come in and clean his room.[25] On the eve of Thanksgiving 1970, he was removed from his room on a stretcher and flown to the Bahamas.[26] After Hughes's death in 1976, the hotel remained under the Summa Corporation, which completed the extensive renovation that he had ordered.[10] Summa sold the hotel to Kirk Kerkorian and the Tracinda Corporation in 1986, and it became known as the MGM Desert Inn. Kerkorian sold it to ITT-Sheraton in 1993 for $160 million.[10]

Modern history

In 1992, Frank Sinatra celebrated his 77th birthday at the hotel in an event which generated much media attention. Dick Taylor, the CEO of public relations firm Rogers & Cowan recalled: "We had the stars assemble in the casino's presidential suite and then took them in limos to the entrance of the hotel, where the press and hundreds of fans were gathered, like a Hollywood movie premiere. The stars were interviewed on the red carpet and in they went to the famed Crystal Room. It was a very big deal."[29]

The property was sold to ITT Sheraton in 1993 for $160 million and renamed the Sheraton Desert Inn.[30] Four years later, in 1997, ITT Sheraton undertook a $200 million renovation of the Augusta Tower and St. Andrews Tower and expansion,[31] with the building and completion of the Palms Tower. The resort was returned to its historic name, The Desert Inn, dropping the Sheraton name, and was placed in the ITT Sheraton Luxury Collection division. ITT Sheraton itself was sold the following year to Starwood.[10] Due to losing money, Starwood immediately put The Desert Inn up for sale, and contracted a sale to Sun International Hotels Ltd. on May 19, 1999 for $275 million.[10][32] The sale to Sun International fell through the following March, however.[30] Also in 1999, Sinatra's and the Rat Pack's estate managers, Sheffield Enterprises Inc., sued the Desert Inn, claiming an infringement of rights in their use of Sinatra's name and persona in its advertising and sales, including the words "Frank", "Ol' Blue Eyes," "the chairman of the Board" and "The Rat Pack". Sinatra's estate specifically objected to their use in "billboard advertising, marquees, alcoholic beverages and wine menus, and on the front and back of tee-shirts and caps at its gift shop" and alleged photographs of Sinatra and his signature on the walls behind the bar near the entrance to the Starlight Lounge of the Desert Inn.[33]

The Desert Inn celebrated its 50th anniversary on April 24, 2000. Celebrations were held for a week and a celebrity golf tournament was held with the likes of Robert Loggia, Chris O'Donnell, Robert Urich, Susan Anton, Vincent Van Patten and Tony Curtis. As part of the festivities, a time capsule was buried in a granite burial chamber on April 25, to be reopened on April 25, 2050.[10] Three days later, on April 27, Steve Wynn purchased the resort from Starwood for $270 million. Wynn closed the Desert Inn at 2:00 a.m. on August 28, 2000.[10]

—Wilbur Clark's Desert Inn Hotel History[34]

On October 23, 2001, the Augusta Tower, the Desert Inn's southernmost building,[35] was imploded to make room for a mega resort that Wynn planned to build.[36] Coming a month after the September 11 attacks, the implosion was marked with less fanfare than previous Las Vegas demolition spectacles due to its similarity to the collapse of the Twin Towers.[37] Originally intended to be named Le Rêve, the new project opened as Wynn Las Vegas. The remaining two towers, the St. Andrews Tower and Palms Tower were both temporarily used as the Wynn Gallery, spanning 1,316 square feet (122.3 m2) to display some of Wynn's art collection.[38] The St. Andrews Tower and Palms Tower were finally imploded on November 16, 2004.[39]

Architecture and features

The initial hotel, a $6.5 million property set in 200 acres, was designed by Hugh Taylor who was hired after Wilbur Clark and Wayne McAllister could not agree on the design. Interiors were by noted New York architect Jac Lessman.[12][40] The property conveyed the image of a "southwestern spa"[41] that was "half ranch house, half nightclub".[12] It was built of "cinder blocks but trimmed with sandstone and finished throughout the inside with redwood".[7] The logo of the hotel was a Joshua tree cactus.[4] The driveway into the hotel passed under an "old-fashioned ranch sign" bearing the name Wilbur Clark's Desert Inn in scripted letters.[12] The Desert Inn was the first hotel in Las Vegas to feature a fountain at the entrance. A "Dancing Waters" show involved the fountain jets choreographed to music.[7]

The interior of the hotel was finished in redwood with flagstone flooring.[12] The public space included a registration area, a casino, two bars, a coffee shop, a restaurant, various commercial shops and services, and a broadcasting station for K-RAM radio.[12] Guest rooms were located in wings situated behind the main building, surrounding the figure-eight swimming pool.[12] The hotel originally had 300 rooms, each outfitted with air conditioning with individual thermostats.[7][22]

The lounge was located in a three-story, glass-sided tower at the front of the hotel known as the Sky Room, which was the largest structure on the Strip at the time of its construction and commanded views of the mountains and desert all around, as well as overlooked the "Dancing Waters" feature.[12][22] The Sky Room restaurant was headed by a chef formerly of the Ritz Paris.[7]

The original performance venue at the Desert Inn was the 450 seat Painted Desert Room, later the Crystal Room, which opened in 1950 with 450 seats. Charles Cobelle created the handpainted murals, and a "band car" was used to move the orchestra within the showroom.[42] Next door was a restaurant, the Cactus Room. The Kachina Doll Ranch was a supervised play area for guests' children.[43] The hotel had a ladies salon and health club from the outset.[8] Another performance venue at the hotel was the Lady Luck Lounge.[44]

The hotel first underwent renovation in the early 1960s, during which the St. Andrews Tower was built in 1963.[45] In the 1970s, the hotel underwent a $54-million renovation under Howard Hughes, which resumed under the responsibility of the Summa Corporation after his death in 1976.[10] The 14-story Augusta Tower became the Desert Inn's main tower when it was completed in 1978. The seven-story Wimbledon Tower contained duplex suites,[3] and resembled a modern version of a Mayan pyramid.[46] It overlooked the golf course and was built at the same time,[47] bringing the total room count to 825.[48] By 1978, most of the 1950s structures on the property had been replaced with modern buildings[48] and the property was renamed the Desert Inn and Country Club. It featured full country club amenities open to guests of the hotel, including a club house, driving range, pro shop, restaurant and lounge at the golf club; 10 tournament-class outdoor tennis courts; and a 18,000 feet (5,500 m) spa.[48][49] Three restaurants were added: the "small, intimate" Monte Carlo Room, the "gourmet" Portofino Room, and the Ho Wan Chinese restaurant.[48] At the time of its sale to ITT-Sheraton in 1993, the Desert Inn had the largest frontage of any casino hotel on the Las Vegas Strip, measuring 1,700 feet (520 m) feet.[50]

In 1997, the Desert Inn underwent a $200 million renovation and expansion by Steelman Partners,[31] giving it a new Mediterranean-looking exterior with white stucco and red clay tile roofs.[51][52] The room count was reduced to 715 to provide more luxurious accommodations.[48] The nine-story Palm Tower was completed, the lagoon-style pool was added, and notable changes were made to the Grand Lobby Atrium, Starlight Lounge, Villas Del Lago, and new golf shop and country club.[10][48] The seven-story lobby, fully built in marble,[51] was also a major part of the renovation.[10]

Casino

At its opening in 1950, the casino, at 2,400 square feet (220 m2), was one of the largest in Nevada at the time.[8] The windowless room included "five crap tables, three roulette wheels, four black jack tables and 75 slot machines", together with a sportsbook.[12] Hundreds of coin-operated gambling machines – including slot machines, video poker, 21, and keno – were installed during the 1978 renovation.[48] The casino acquired a reputation for attracting the high rollers.[53] On January 27, 2000, the Megabucks jackpot record for Las Vegas was broken when $34,955,489 was won by an anonymous gambler at the Desert Inn, playing a bank of six Megabucks machines near the hotel's coffee shop.[54]

Golf course and country club

The 18-hole, par-72[49] Desert Inn Golf Club opened in 1952. Initially, Dalitz had pushed the idea of opening a golf course next to the hotel with an entrance off the Strip, which would be accessible to other hotels and boost the city's profile as a resort destination. When other hotel owners rejected this idea, Dalitz built the course on the hotel premises.[55] He also opened an outdoor dining area, to accommodate golfers and swimmers who might prefer a more informal atmosphere.[56] The course hosted the PGA Tour Tournament of Champions from 1953 to 1966,[45] attracting professional golfers such as Sam Snead, Arnold Palmer, and Jack Nicklaus.[55] Allard Roen was director of the tournament for many years, and was instrumental in breaking down the racial barrier on the Strip. He broke the all-white club convention by permitting Sammy Davis, Jr. to play on the course.[57] From 1958 it hosted the Golf Cup Golf Tournament, the largest tournament in the world for amateur golfers.[58]

According to the Las Vegas Sun, the course "held the distinction of being the only golf course in the United States to have annually hosted three championship tour events – the PGA Tour's Las Vegas Invitational, the Las Vegas Senior Classic and the LPGA Las Vegas International".[58] The Panasonic Las Vegas Invitational, now the Las Vegas Invitational, returned to the Desert Inn in 1983, and became known as the wealthiest PGA event in the world. It has since been won by the likes of Fuzzy Zoeller, Curtis Strange, Greg Norman, and Paul Azinger. The Las Vegas Senior Classic event at the Desert Inn was added to the Senior PGA Tour in 1986, and has since been won by Bruce Crampton (1986), Al Geiberger, who equaled the course record at the time of 62 (1987), Larry Mowry (1988) and Lee Trevino (1992).[58]

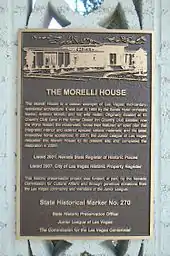

Wilbur Clark was the first to build a home on the golf course in the 1950s.[12] Additional homes were added to the Desert Inn Country Club Estates from the 1960s on. During his ownership of the hotel, Howard Hughes built 100 residential units on the property.[59] After Steve Wynn purchased the resort in 2000 and announced that the real estate was too valuable to leave as a golf course, homeowners were forced to sell their properties to Wynn and his property developer Irwin Molasky. Molasky bought homes closest to the golf course for $2 million each, and homes on the perimeter of the resort for $900,000 to $1.2 million each. The Junior League of Las Vegas convinced Wynn to save one house from demolition and moved it to a lot in downtown Las Vegas to serve as its headquarters.[34][60] This was the Morelli House, designed by architect Hugh Taylor for Antonio Morelli, a "rare example of modernist architecture in Las Vegas".[60] The house was subsequently listed on the City and State historic registers.

Performances

Almost every major star of the latter half of the 20th century played at the Desert Inn. Frank Sinatra made his Las Vegas debut at the Desert Inn on September 13, 1951. He later said of it: "Wilbur Clark gave me my first job in Las Vegas. That was in 1951. For six bucks you got a filet mignon dinner and me".[11] Noël Coward performed at the Inn on one occasion for an entire month.[7] In 1954, after a performance at the Desert Inn, Betty Hutton announced one of her several retirements.[61] In 1958, Tony Martin was signed to a five-year deal at $25,000 per week, making him the highest paid performer in Las Vegas.[62] Eddie Fisher was heckled by a disguised Elizabeth Taylor during a 1961 performance,[63] in a year which saw Dinah Shore booked for her fourth performance and debut Vegas performances at the Desert Inn by both Benny Goodman and Rosemary Clooney.[64] In 1979, Jet magazine noted that Wayne Newton was "enthroned" at the Desert Inn as king of entertainment idols", earning $10 million a year, which made him the highest-paid nightclub performer of all time.[65] Other performers in its famous "crystal showroom" over the years included Patti Page,[66] Ted Lewis,[44] Joe E. Lewis,[67] Bobby Darin,[68] Jimmy Durante,[22] Tony Bennett,[69] Paul Anka,[70] Dionne Warwick,[71] Louise Mandrell,[72] and more.

Louis Prima and Keely Smith recorded their 1960 Dot Records LP On Stage live at the Desert Inn.[73] Bobby Darin's famous album Live! At the Desert Inn was recorded at the hotel in February 1971.[68] In 1992, a week-long celebration of Frank Sinatra's 77th birthday at the Desert Inn was held[74] and later in January it was announced that Sinatra, Liza Minnelli, Paul Anka, Shirley MacLaine, Dean Martin, Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme had all signed a two-year engagement agreeing to perform at least five weeks annually.[75]

Film and television

Portions of Ocean's 11 were shot at the Desert Inn. It is one of the five Las Vegas hotels robbed on New Year's Eve by the characters played by Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and others in the film.[76] Orson Welles' film F for Fake covers, among other topics, the scandal of a fake biography of Howard Hughes, and the billionaire's Desert Inn residence is illustrated by Welles.[77] In the 1985 film Lost in America, Julie Hagerty's character Linda Howard loses the couple's "nest egg" at the Desert Inn, leading to a memorable scene in which Albert Brooks' character David Howard tries to convince the Casino manager (Garry Marshall) to give them their money back. David, an ad man, proposes a campaign centered around the generosity of the casino in his case, replete with a jingle: "The Desert Inn has heart... The Desert Inn has heart."[78] The opening scene to the 1993 film Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit took place in the Grand Ballroom of the hotel.[79] The Desert Inn saw its last commercial use in the 2001 film Rush Hour 2, shortly before it was imploded.[80] It was converted into the "Red Dragon", an Asian-themed casino set.[81]

The hotel served as the primary backdrop for the TV show Vega$ which aired on ABC from 1978 to 1981.[82][83] The 1980s Aaron Spelling soap opera Dynasty included footage of the hotel, and use of the Presidential Suite.[84] The hit 1980s NBC TV series Remington Steele filmed its 60th Las Vegas-set episode at the inn, where both the exterior and interior are shown regularly throughout the episode.[85]

Legacy

The closure of the Desert Inn in 2000 and subsequent demolition was unpopular with many as it seemed to mark the end of old Las Vegas. Historian Michael Green stated: "To a lot of people outside of Las Vegas, these two places (the Desert Inn and the Sands) really meant Las Vegas. These were the places that represent the images of Las Vegas, in a far greater way than the Dunes, the Aladdin, the Hacienda and the Landmark".[86] Robert Maheu, Howard Hughes's head of Nevada operations and publicist for many years, remarked that the "Desert Inn was the gem of Las Vegas". The hotel remained popular with locals until the end, as the heavily tourism-driven modern Las Vegas emerged in the 1990s.[87]

Desert Inn Road

Desert Inn Road, an east–west Las Vegas Valley roadway, still exists. It is the only major east–west surface street on the Strip that does not connect to Las Vegas Boulevard.[88]

- Major intersections

The entire route is in Clark County.

| Location | mi[89] | km | Destinations | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summerlin South | 0.00 | 0.00 | Red Rock Ranch Road / Flamingo Road | Western terminus | |

| 0.4 | 0.64 | Bridge over CC 215 (Bruce Woodbury Beltway); no access to beltway | |||

| Spring Valley | 5.5 | 8.9 | Rainbow Boulevard (SR 595) | ||

| 6.5 | 10.5 | Jones Boulevard (SR 596) | |||

| Las Vegas–Paradise line | 9.0 | 14.5 | Rancho Drive | Interchange; eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |

| 9.05 | 14.56 | Highland Drive | Interchange; eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| Bridge over I-15; no access to freeway | |||||

| Paradise–Winchester line | 9.9 | 15.9 | Tunnel underneath Las Vegas Boulevard | ||

| 14.2 | 22.9 | Underpass beneath I-515 (I-11); no access to freeway | |||

| Paradise–Winchester– Sunrise Manor tripoint | 14.5 | 23.3 | Boulder Highway (SR 582) | ||

| Paradise–Sunrise Manor line | 15.6 | 25.1 | Nellis Boulevard (SR 612) | ||

| Sunrise Manor | 17.1 | 27.5 | Theme Road | Continuation south beyond eastern terminus | |

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| |||||

References

Citations

- "Wynn Buys Desert Inn as Gift for Wife". Los Angeles Times. April 28, 2000.

- Matuszewski, Erik (November 12, 2018). "Wynn Golf Club In Las Vegas To Re-Open In 2019 After Being Closed For Development". Forbes. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Bulkin 1996, p. 49.

- Kaplan 2010, p. 242.

- Rothman 2015, p. 13.

- Denton & Morris 2010, p. 62.

- Fox 2007, p. 31.

- Russo 2008, p. 206.

- Koch, Ed; Manning, Mary; Toplikar, Dave (May 15, 2008). "Showtime: How Sin City evolved into 'The Entertainment Capital of the World'". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- "History". A2zlasvegas.com. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Russo 2008, p. 207.

- "Wilbur Clark's Desert Inn Hotel History – 1950s". Classic Las Vegas. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Russo 2008, p. 208.

- "How 1950s Las Vegas sold atomic bomb testing as tourism". /www.si.edu/. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- "Atomic tests were a tourist draw in 1950s Las Vegas". citylab.com. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- "Atomic Cocktail". diffordsguide.com. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- "Who are you miss atomic bomb". popularmechanics.com. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- "Las Vegas NV Atomic Testing Museum". roadsideamerica.com. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- "Real Estate Man Buys the Desert Inn". The Ludington Daily News. Ludington, Michigan. August 17, 1959. p. 1. Retrieved December 16, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- Kelley 1986, pp. 363–364.

- Waldman & Donovan 1999, p. 139.

- "Desert Inn". Online Nevada. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "Governor Asks Trial of FBI for Wiretap". The Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Corpus Christi, Texas. June 29, 1966. p. 1. Retrieved December 16, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- Katsilometes, John (April 20, 2000). "Desert Inn celebrates its golden anniversary". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "People and Events: Howard Hughes (1905–1976)". PBS. 2005. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- Manning, Mary (May 15, 2008). "Howard Hughes: A revolutionary recluse". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- Davies 1999, p. 39.

- Davies 1999, pp. 39–40.

- "Frank Sinatra hoopla eclipses Lennon, Elvis and Billie". The Desert Sun. December 7, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- http://www.a2zlasvegas.com/hotels/history/h-di.html

- Global Equity Research. UBS Warburg. 2004. p. 10.

- "Sun Will Buy Desert Inn for $275 Million". Los Angeles Times. May 19, 1999.

- Leong, Grace (September 9, 1999). "Sinatra estate sues Desert Inn". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "Wilbur Clark's Desert Inn Hotel History (continued)". Classic Las Vegas. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "Wynn's Plans for Desert Inn Revealed". The Los Angeles Times. August 28, 2001. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- Garman 2010, p. 278.

- Easterling 2005, p. 160.

- "Wynn plans water theme at DI site". Las Vegas Sun. August 23, 2001. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "The Desert Inn Implosion". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "Jac Lessman 85, Dies; Hotel-Resort Developer". The New York Times. November 8, 1990. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- Moehring 2003, pp. 14–15.

- Zook, Burke & Sandquist 2009, p. 134.

- Architect and Engineer 1950, p. 15.

- Jet Age Airlanes. Ayre Publishing Company. 1965.

- Casino Journal: National ed. Casino Journal of Nevada, Incorporated. January 2000.

- Wood, Lanier & Zoeller 1992, p. 149.

- Castleman 1999, p. 84.

- "Wilbur Clark's Desert Inn Hotel History (continued)". Classic Las Vegas. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Michele and Tom Grimm (October 1992). "The West's Hottest Desert Resorts". Orange Coast: 88.

- McDowell, Edwin (June 29, 1993). "COMPANY NEWS; ITT Buying Desert Inn In Las Vegas". The New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "Living it Up and Doubling Down in the New Las Vegas". The New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Time Out Las Vegas. Penguin. 1998. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-14-027062-4.

- Strow, David (April 24, 2000). "Desert Inn marks 50th anniversary". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "Record Megabucks jackpot hit at Desert Inn". Las Vegas Sun. January 27, 2000. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Davies 1999, p. 32.

- "Las Vegas Inn Opens Patio for Outdoor Dining". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. June 8, 1952. p. 19. Retrieved December 16, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Desert Inn, Stardust chief helped integrate Las Vegas Strip". Las Vegas Sun. September 1, 2008. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "Desert Inn rich in tradition". Las Vegas Sun. October 20, 1997. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Moehring 2003, p. 55.

- Schumacher, Geoff (April 17, 2003). "Cover story: This old town". Las Vegas Mercury. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- "The End". Pampa Daily News. Pampa, Texas. November 11, 1954. p. 1. Retrieved December 16, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Tony Martin's $1,000,000 Deal". Variety. November 19, 1958. p. 1. Retrieved July 8, 2019 – via Archive.org.

- "Heckler Disguised". The Oneonta Star. Oneonta, New York. June 15, 1961. p. 1. Retrieved December 16, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Top Names Booked for Desert Inn". Independent. Long Beach, California. March 16, 1961. p. 70. Retrieved December 16, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- Vegas Idol Wayne Newton Calls Lola Falana Show Biz 'Decathlon Artist'. Jet. May 17, 1979. p. 22. ISSN 0021-5996.

- Current Biography Yearbook. H. W. Wilson Co. 1966. p. 310.

- Winchell 1975, p. 236.

- DiOrio 1981, p. 199.

- Evanier 2011, p. 239.

- Weatherford 2001, p. 40.

- Racing Pigeon Bulletin. 1979.

- Roemer 1990, p. 100.

- Larkin 2002, p. 342.

- "Sinatra Marks 77th Birthday". The Titusville Herald. Titusville, Pennsylvania. January 3, 1992. p. 10. Retrieved December 16, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Stars Sign Contracts with Desert Inn". The Titusville Herald. Titusville, Pennsylvania. January 16, 1992. p. 3. Retrieved December 16, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- Davis & Pierce 2014, p. 86.

- Graver & Rausch 2011, p. 76.

- Rothman & Davis 2002, pp. 49–51.

- "Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit script". Script-o-rama.com. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Parker & Munier 2010, p. 169.

- The Bulletin. J. Haynes and J.F. Archibald. 2001. p. 174.

- Spelling & Liftin 2009, p. 29.

- Clarke 2004, p. 178.

- Cosmopolitan. Hearst Corporation. January 1985. p. 1.

- "Episode 60". Pbfiles.net. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- "Wynn's closure of Desert Inn strikes nerve with community". Las Vegas Sun. August 25, 2000. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "Desert Inn site carries a rich past". Las Vegas Sun. April 28, 2005. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Google (December 17, 2015). "Desert Inn" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- "Overview of Desert Inn Road". Google Maps. Google, Inc. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

Sources

- Architect and Engineer (1950). Architect and Engineer. Issues 80–183. San Francisco: Architect and Engineer.

- Bulkin, Rena (December 1996). Frommer's Las Vegas, 1997. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-02-860917-1.

- Castleman, Deke (1999). Compass American Guide to Las Vegas. Fodor's Travel Publications. ISBN 978-0-679-00370-0.

- Clarke, Norm (January 8, 2004). Vegas Confidential: Norm Clarke! Sin City's Ace Insider 1,000 Naked Truths. Stephens Press, LLC. ISBN 978-1-932173-26-0.

- Davis, Tracey; Pierce, Nina Bunche (April 22, 2014). Sammy Davis Jr.: A Personal Journey with My Father. Running Press Book Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7624-5017-6.

- DiOrio, Al (1981). Borrowed Time: The 37 Years of Bobby Darin. Running Press. ISBN 978-0-89471-111-4.

- Davies, Richard O. (1999). The Maverick Spirit: Building the New Nevada. University of Nevada Press. p. 32. ISBN 0874173272.

- Denton, Sally; Morris, Roger (September 30, 2010). The Money And The Power: The Rise and Reign of Las Vegas. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4090-0203-1.

- Evanier, David (June 30, 2011). All the Things You Are: The Life of Tony Bennett. John Wiley & Sons. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-118-03354-8.

- Graver, Gary; Rausch, Andrew J. (October 28, 2011). Making Movies with Orson Welles. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8229-4.

- Easterling, Keller (2005). Enduring Innocence: Global Architecture and Its Political Masquerades. MIT Press. ISBN 026205079X.

- Fox, William L. (2007). In the Desert of Desire: Las Vegas and the Culture of Spectacle. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 978-0-87417-727-5.

- Garman, Rick (2010). Las Vegas for Dummies (6th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0470944420.

- Kaplan, James (November 4, 2010). Frank: The Making of a Legend. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-0-7481-2250-9.

- Kelley, Kitty (1986). His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra. Bantam Books Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-553-38618-9.

- Larkin, Colin (2002). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Fifties Music. Virgin Books. ISBN 978-1-85227-937-0.

- Moehring, Eugene (2003). "The Sahara Hotel: Las Vegas' "Jewel in the Desert"". In Jaschke, Karin; Ötsch, Silke (eds.). Stripping Las Vegas: A Contextual Review of Casino Resort Architecture. Verl.d. Bauhaus-Universität. ISBN 3860681923.

- Parker, Quentin; Munier, Paula (December 18, 2010). The Sordid Secrets of Las Vegas: Over 500 Seedy, Sleazy, and Scandalous Mysteries of Sin City. Adams Media. ISBN 1-4405-1194-2.

- Roemer, William F. (1990). War of the Godfathers: The Bloody Confrontation Between the Chicago and New York Families for Control of Las Vegas. Donald I. Fine. ISBN 978-1-55611-193-8.

- Rothman, Hal; Davis, Mike (2002). The Grit Beneath the Glitter: Tales from the Real Las Vegas. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22538-1.

- Rothman, Hal (October 15, 2015). Neon Metropolis: How Las Vegas Started the Twenty-First Century. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-95852-9.

- Russo, Gus (December 12, 2008). Supermob: How Sidney Korshak and His Criminal Associates Became America's Hidden Power Brokers. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59691-898-6.

- Spelling, Tori; Liftin, Hilary (February 24, 2009). STORI Telling. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-8700-2.

- Waldman, Carl; Donovan, Jim (February 1, 1999). Forever Sinatra: A Celebration in Words & Images. Legends Press. ISBN 978-0-9668136-0-9.

- Weatherford, Mike (January 1, 2001). Cult Vegas: The Weirdest! the Wildest! the Swingin'est Town on Earth!. Huntington Press Inc. ISBN 978-0-929712-71-0.

- Winchell, Walter (October 1975). Winchell exclusive: "things that happened to me—and me to them. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-960286-3.

- Wood, Robert S; Lanier, Pamela; Zoeller, Fuzzy (April 1992). Golf Resorts: The Complete Guide. Lanier Pub. International. ISBN 978-0-89815-476-4.

- Zook, Lynn; Burke, Carey; Sandquist, Allen (March 2, 2009). Las Vegas: 1905–1965. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-2310-7.

External links

- Video of Desert Inn implosion, October 23, 2001

- Jac Lessman architectural records and papers, 1925-1975. Held by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Desert Inn. |