Las Vegas Strip

The Las Vegas Strip is a stretch of South Las Vegas Boulevard in Clark County, Nevada, that is known for its concentration of resort hotels and casinos. The Strip, as it is known, is about 4.2 mi (6.8 km) long,[1] and is immediately south of the Las Vegas city limits in the unincorporated towns of Paradise and Winchester, but is often referred to simply as "Las Vegas".

| The Strip South Las Vegas Boulevard | |

.jpg.webp)   .jpg.webp) .jpg.webp)   Clockwise from top: Las Vegas Boulevard, MGM Grand Las Vegas, New York-New York, The Venetian Las Vegas, Caesars Palace, Bally's Las Vegas & Paris Las Vegas, Bellagio | |

| Length | 4.2 mi (6.8 km) |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36.119684°N 115.172599°W |

| South end | Russell Road |

| North end | Sahara Avenue |

Many of the largest hotel, casino, and resort properties in the world are on the Strip, known for its contemporary architecture, lights, and wide variety of attractions. Its hotels, casinos, restaurants, residential high-rises, entertainment offerings, and skyline have established the Strip as one of the most popular and iconic tourist destinations in the world and is one of the driving forces for Las Vegas' economy.[2] Most of the Strip has been designated as an All-American Road[3] and the North and South Las Vegas Strip routes are classified as Nevada Scenic Byways and National Scenic Byways.[4]

Boundaries

Historically, area casinos that were not in Downtown Las Vegas along Fremont Street sat outside the city limits on Las Vegas Boulevard.[5][6] In 1959, the Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas sign was built[7] exactly 4.5 miles (7.2 km) outside the city limits. The sign is currently located in the median just south of Russell Road, across from the location of the now-demolished Klondike Hotel and Casino and about 0.4 miles (0.64 km) south of the southernmost entrance to Mandalay Bay, which is the Strip's southernmost casino.

In the strictest sense, "the Strip" refers only to the stretch of Las Vegas Boulevard that is roughly between Sahara Avenue and Russell Road, a distance of 4.2 miles (6.8 km).[8][9][10] However, the term is often used to refer not only to the road but also to the various casinos and resorts that line the road, and even to properties that are near but not on the road. Phrases such as Strip Area, Resort Corridor or Resort District are sometimes used to indicate a larger geographical area, including properties 1 mile (1.6 km) or more away from Las Vegas Boulevard, such as the Westgate Las Vegas, Hard Rock, Rio, Palms, and Oyo resorts.

The Sahara is widely considered the Strip's northern terminus, though travel guides typically extend it to the Strat 0.4 miles (0.64 km) to the north.[11][12][13] Mandalay Bay, just north of Russell Road, is the southernmost resort considered to be on the Strip[11] (the Klondike was the southernmost until 2006, when it was closed, although it was not included in the Strip on some definitions and travel guides). The "Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas" sign is often considered part of the Strip,[11] although it sits 0.4 miles south of the Mandalay Bay and Russell Road.

Because of the number and size of the resorts, the resort corridor can be quite wide. Interstate 15 runs roughly parallel and 0.5 to 0.8 miles (0.80 to 1.29 km) to the west of Las Vegas Boulevard for the entire length of the Strip. Paradise Road runs to the east in a similar fashion, and ends at St. Louis Avenue. The eastern side of the Strip is bounded by McCarran International Airport south of Tropicana Avenue.

North of this point, the resort corridor can be considered to extend as far east as Paradise Road, although some consider Koval Lane as a less inclusive boundary. Interstate 15 is sometimes considered the western edge of the resort corridor from Interstate 215 to Spring Mountain Road. North of this point, Industrial Road serves as the western edge.

Newer hotels and resorts such as South Point, Grandview Resort, and M Resort are on Las Vegas Boulevard South as distant as 8 miles south of the "Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas" sign. Marketing for these casinos and hotels usually states that they are on southern Las Vegas Boulevard and not "Strip" properties.

- Las Vegas Strip ~ Day and Night

History

Early years (1930s–1990s)

The first casino to be built on Highway 91 was the Pair-o-Dice Club in 1931, but the first casino-resort on what is currently the Strip was the El Rancho Vegas, which opened with 63 rooms on April 3, 1941 (and was destroyed by a fire in 1960). Its success spawned a second hotel on what would become the Strip, the Hotel Last Frontier in 1942. Organized crime figures such as New York's Bugsy Siegel took interest in the growing gaming center, and funded other resorts such as the Flamingo, which opened in 1946, and the Desert Inn, which opened in 1950. The funding for many projects was provided through the American National Insurance Company, which was based in the then-notorious gambling empire of Galveston, Texas.[14][15]

Las Vegas Boulevard South was previously called Arrowhead Highway, or Los Angeles Highway. The Strip was named by Los Angeles police officer and businessman Guy McAfee, after his hometown's Sunset Strip.[16]

In 1950, mayor Ernie Cragin of the City of Las Vegas sought to annex the Strip, which was unincorporated territory, in order to expand the city's tax base to fund his ambitious building agenda and pay down the city's rising debt.[17] Instead, Gus Greenbaum of the Flamingo led a group of casino executives to lobby the Clark County commissioners for town status.[17] Two unincorporated towns were eventually created, Paradise and Winchester.[18][19] More than two decades later, the Supreme Court of Nevada struck down a 1975 Nevada state law that would have folded the Strip and the rest of the urban areas of Clark County into the City of Las Vegas.[20]

Caesars Palace was established in 1966. In 1968, Kirk Kerkorian purchased the Flamingo and hired Sahara Hotels Vice President Alex Shoofey as president. Alex Shoofey brought along 33 of Sahara's top executives. The Flamingo was used to train future employees of the International Hotel, which was under construction. Opening in 1969, the International Hotel, with 1,512 rooms, began the era of mega-resorts. The International is known as Westgate Las Vegas today. The first MGM Grand Hotel and Casino, also a Kerkorian property, opened in 1973 with 2,084 rooms. At the time, this was one of the largest hotels in the world by number of rooms. The Rossiya Hotel built in 1967 in Moscow, for instance, had 3,200 rooms; however, most of the rooms in the Rossiya Hotel were single rooms of 118 sq. ft (roughly 1/4 size of a standard room at the MGM Grand Resort). On November 21, 1980, the MGM Grand suffered the worst resort fire in the history of Las Vegas as a result of electrical problems, killing 87 people. It reopened eight months later. In 1986, Kerkorian sold the MGM Grand to Bally Manufacturing, and it was renamed Bally's.

The Wet 'n Wild water park opened in 1985 and was located on the south side of the Sahara hotel. It closed at the end of the 2004 season and was later demolished. The opening of The Mirage in 1989 set a new level to the Las Vegas experience, as smaller hotels and casinos made way for the larger mega-resorts. The Rio and the Excalibur opened in 1990. These huge facilities offer entertainment and dining options, as well as gambling and lodging. This change affected the smaller, well-known and now historic hotels and casinos, like the Dunes, the Sands, and the Stardust.

The lights along the Strip have been dimmed in a sign of respect to six performers and one other major Las Vegas figure upon their deaths. They are Elvis Presley (1977), Sammy Davis Jr. (1990),[21] Dean Martin (1995), George Burns (1996), Frank Sinatra (1998), former UNLV basketball head coach Jerry Tarkanian (2015),[22] and Don Rickles (2017).[23] The Strip lights were dimmed later in 2017 as a memorial to victims of a mass shooting at a concert held adjacent to the Strip.[24] In 2005, Clark County renamed a section of Industrial Road (south of Twain Avenue) Dean Martin Drive as a tribute to the famous Rat Pack singer, actor, and frequent Las Vegas entertainer.

In an effort to attract families, resorts offered more attractions geared toward youth, but had limited success. The current MGM Grand opened in 1993 with MGM Grand Adventures Theme Park, but the park closed in 2000 due to lack of interest. Similarly, in 2003 Treasure Island closed its own video arcade and abandoned the previous pirate theme, adopting the new ti name.[25]

In addition to the large hotels, casinos and resorts, the Strip is home to many attractions, such as M&M's World, Adventuredome and the Fashion Show Mall. Starting in the mid-1990s, the Strip became a popular New Year's Eve celebration destination.

.jpg.webp)

2000–present

.jpg.webp)

With the opening of Bellagio, Venetian, Palazzo, Wynn and Encore resorts, the strip trended towards the luxurious high end segment through most of the 2000s, while some older resorts added major expansions and renovations, including some de-theming of the earlier themed hotels. High end dining, specialty retail, spas and nightclubs increasingly became options for visitors in addition to gambling at most Strip resorts. There was also a trend towards expensive residential condo units on the strip.

In 2004, MGM Mirage announced plans for CityCenter, a 66-acre (27 ha), $7 billion multi-use project on the site of the Boardwalk hotel and adjoining land. It consists of hotel, casino, condo, retail, art, business and other uses on the site. City Center is currently the largest such complex in the world. Construction began in April 2006, with most elements of the project opened in late 2009. Also in 2006, the Las Vegas Strip lost its longtime status as the world's highest-grossing gambling center, falling to second place behind Macau.[26]

In 2012, the High Roller Ferris wheel and a retail district called The LINQ Promenade broke ground in an attempt to diversify attractions beyond that of casino resorts. Renovations and rebrandings such as The Cromwell Las Vegas and the SLS Las Vegas continued to transform the Strip in 2014. The Las Vegas Festival Grounds opened in 2015. In 2016, T-Mobile Arena, The Park, and the Park Theater opened.

On October 1, 2017, a mass shooting occurred on the Strip at the Route 91 Harvest country music festival, adjacent to the Mandalay Bay hotel. 60 people were killed and 867 were injured. This incident became the deadliest mass shooting in modern United States history.[27][28][29]

In 2018, the Monte Carlo Resort and Casino was renamed the Park MGM and 2019, the SLS retook its Sahara name.[30][31]

Future developments

- Genting Group bought the site of the Stardust/Echelon Place with plans to build and open Resorts World Las Vegas in summer 2021.[32]

- Astral Hotels plans to build Astral, a 34-story, 620-room hotel and casino on the southern Las Vegas Strip. Construction is expected to begin in 2020 for a 2022 opening.[33]

- Dream Las Vegas, a casino and boutique hotel, is planned to break ground on the southern Las Vegas Strip by early 2021, with completion by early 2023.[34][35]

- The opening of 4,000 room The Drew Las Vegas (formerly planned as the Fontainebleau) has been pushed back to the second quarter of 2022.[36]

- As of June 2019, construction of the All Net Resort and Arena is expected to start "as soon as possible" and will take about 3 years.[37]

- The MSG Sphere Las Vegas, including a monorail stop, is being built behind The Palazzo and The Venetian. It was scheduled to open in 2021, but has been rescheduled to sometime in 2023.[38]

Transportation

Buses

RTC Transit (previously Citizens Area Transit, or CAT) provides bus service on the Strip with double decker buses known as The Deuce.[39] The Deuce runs between Mandalay Bay at the southern end of the Strip (and to the Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas sign and South Strip Transfer Terminal after midnight) to the Bonneville Transit Center (BTC) and the Fremont Street Experience in Downtown Las Vegas, with stops near every casino. RTC also operates an express bus called the Strip and Downtown Express (SDX).[39] This route connects the Strip to the Las Vegas Convention Center and Downtown Las Vegas to the north, with stops at selected hotels and shopping attractions (Las Vegas Premium Outlets North & South).

Trams

Several free trams operate between properties on the west side of the Strip:[40]

- Mandalay Bay Tram connecting the Mandalay Bay, Luxor, and Excalibur

- Aria Express connecting Park MGM, Crystals (also stop for Aria), and Bellagio)

- Mirage-Treasure Island Tram runs between Treasure Island and The Mirage

The Deuce bus

The Deuce bus Aria Express

Aria Express

Monorail

While not on the Strip itself, the Las Vegas Monorail runs a 3.9 mile route on the east side of the Strip corridor from Tropicana Avenue to Sahara Avenue, with stops every 4 to 8 minutes at several on-Strip properties including the MGM Grand and the Sahara at each end of the route.[41][42] The stations include:[42]

- SAHARA Las Vegas Station

- Westgate Station

- Las Vegas Convention Center Station

- Harrah's/The LINQ Station

- Flamingo/Caesars Palace Station

- Bally's/Paris Station

- MGM Grand Station

Pedestrian traffic

On a daily basis, there are tens of thousands of pedestrians walking along the Strip.[43] As of 2019, the daily number of pedestrians on the Strip is approximately 50,000.[44]

Concerning pedestrian safety and to help alleviate traffic congestion at popular intersections, several pedestrian footbridges were erected in 1990s and the first was the Tropicana – Las Vegas Boulevard footbridge.[45][46] Some feature designs that match the theme of the nearby resorts. Additional footbridges have been built on Las Vegas Boulevard.[47][48] The footbridges include:[49]

- Veer Towers:. Connects Veer Towers, Waldorf Astoria, and Crystals Shopping Center

- Park MGM and T-Mobile Arena Park: Connects MGM and Showcase Mall

- Planet Hollywood: Connects Planet Hollywood, CityCenter, Crystals Shopping Center, and The Cosmopolitan.

- Spring Mountain Road and Las Vegas Blvd. Corner: Connects Treasure Island, The Wynn, Fashion Show Mall, and The Venetian

- Flamingo Road and Las Vegas Blvd. Corner: Connects Bally's, Flamingo, Bellagio, and Caesars Palace

- Las Vegas Blvd and Tropicana Ave Corner. Connects the MGM Grand, New York-New York, Excalibur, and Tropicana

There has been negative feedback from pedestrians about the elevated crosswalks due to need to walk as much as a quarter-mile to reach an intersection to cross the street and to then walk back some distance on the other side of the street to get to their desired destinations.[50]

After a driver drove into pedestrians on the sidewalk in front of Paris Las Vegas and Planet Hollywood in December 2015, additional bollards were installed on Las Vegas Blvd.[51] In 2019, the bollards on Las Vegas Blvd. were shortened due to feedback from drivers that the bollards were obstructing street views.[52] 283 of the 4,500 bollards will be shortened from 54 inches to 36 inches.[53]

Studies conducted by Clark County in 2012 and 2015 identified issues with congestion.[54][55] The studies resulted in $5 million of improvements, including LED lights, ADA ramps, containment fencing, widening sidewalks, and removing permanent obstructions, such as signs, signposts, trash cans, and fire hydrants.[54][55] The studies also identified non-permanent obstructions causing congestion, such as street performers, vendors, handbillers, signholders, and illegal street gambling.[55] Modifications to non-obstruction zones and increased enforcement were implemented in order to reduce congestion.[55]

Taxis

Taxis are available at resorts, shopping centers, attractions, and for scheduled pickups.[56] The Nevada Taxicab Authority provides information about taxi fares and fare zones.[57]

Rideshares

Rideshare services, including Uber and Lyft, are available on the Strip.[58]

Attractions on the Strip

Gambling

In 2019, about eight in ten (81%) visitors said they gambled while in Las Vegas, the highest proportion in the past five years.[59] The average time spent gambling, 2.7 hours, represents an increase over the past three years.[59] Also, the average trip gambling budget, $591.06, was increased from 2018.[59] About nine in ten (89%) visitors who gambled gambled on the Strip Corridor.[59] UNLV reported that in 2019, Big Las Vegas Strip Casinos (defined as Strip casinos with more than $72M in annual gaming revenues) had more than $6B in annual gaming revenues, corresponding to about 26% of total annual revenues.[60]

From the time period spanning 1985 to 2019, there have been some changes in the mix of table games in casinos on the Strip:[61]

- Blackjack: The number of tables decreased from 77% in 1985 to 50% in 2019. Revenue decreased from 50% in 1985 to 11% in 2019.

- Craps: Revenue decreased from 28% in 1985 to 11% in 2019.

- Roulette: Both the number of tables and revenue increased by 50%.

- Baccarat: About 2% of tables and 13% revenue in 1985 to 13% of tables and 37% of revenue in 2019.

- Additional games: Games such as pai gow poker, three-card poker, and mini-baccarat have increased in popularity, number of tables, and revenue.

Casino operators have been expanding sports betting facilities and products, as well as renovating and upgrading equipment and facilities.[62] Although sports betting has a relatively low margin, the high-end sportsbooks can generate significant amounts of revenue in other areas, such as food and drink.[62] As a result, sportsbooks have been expanding and upgrading foot and drink offerings.[63] High-end sportsbooks include features such as single-seat stadium-style seating, large high-definition screens, a dedicated broadcast booth, and the ability to watch up to 15 sporting events at once.[62][64] The sports network ESPN is broadcasting sports betting shows from a dedicated studio at The Linq.[64] Some sportsbooks are now offering self-service betting kiosks.[65]

Entertainment

The Las Vegas Strip is well known for its lounges, showrooms, theaters and nightclubs;[66] most of the attractions and shows on the Strip are located on the hotel casino properties. Some of the more popular free attractions visible from the Strip include the water fountains at Bellagio, the volcano at The Mirage, and the Fall of Atlantis and Festival Fountain at Caesars Palace. There are several Cirque du Soleil shows, such as Kà at the MGM Grand, O at Bellagio, Mystère at Treasure Island, and Michael Jackson: One at Mandalay Bay.[67]

Many notable artists have performed in Las Vegas, including Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Wayne Newton, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr. and Liberace,[68] and in more recent years Celine Dion, Britney Spears, Barry Manilow, Cher, Elton John, Bette Midler, Diana Ross, Donny and Marie Osmond, Garth Brooks, Jennifer Lopez, Reba McEntire, Mariah Carey, Shania Twain, Criss Angel, Olivia Newton-John, Queen + Adam Lambert, and Lady Gaga have had residencies in the various resorts on the Strip. The only movie theatre directly on the Strip was the 10-screen Regal Showcase Theatre in the Showcase Mall. The theater opened in 1997 and was operated by Regal Entertainment Group,[69] until its closure in 2018.[70] During 2019, 51% of visitors attended shows, which was down from 2015, 2017, and 2018.[71] Among visitors who saw shows, relatively more went to Broadway/production shows than in past years, while relatively fewer saw lounge acts, comedy shows, or celebrity DJs.[71]

Venues

The Strip is home to many entertainment venues. Most of the resorts have a showroom, nightclub and/or live music venue on the property and a few have large multipurpose arenas. Major venues include:

Shopping

- Bonanza Gift Shop is billed as the "World's Largest Gift Shop", with over 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2) of shopping space.

- The Shoppes at the Palazzo featuring luxury stores.

- Fashion Show Mall is adjacent to Treasure Island and opposite Wynn Las Vegas.

- Grand Canal Shoppes is a luxury mall connected to The Venetian with canals, gondolas and singing gondoliers.

- The LINQ Promenade is an open-air retail, dining, and entertainment district located between The Linq and Flamingo resorts that began a soft open in January 2014. It leads from a Strip-side entrance to the High Roller.

- Miracle Mile Shops is part of the Planet Hollywood hotel.

- The Forum Shops at Caesars is a luxury mall connected to Caesars Palace, with more than 160 shops and 11 restaurants.

- Crystals at CityCenter is a luxury high-fashion mall at CityCenter.

- Harmon Corner is a three-story retail center located next to Planet Hollywood with shops and restaurants.

- Showcase Mall is next to MGM Grand, and displays a 100-foot Coca-Cola bottle.[72]

- The Park, a short east–west street between the Park MGM and New York-New York resorts is a park-like boulevard lined with retail shops and restaurants, leading to T-Mobile Arena.[73]

Live sports

Professional sports are found at venues on or near the Strip, including:[74]

- National Football League: Las Vegas Raiders at Allegiant Stadium

- National Hockey League: Vegas Golden Knights: at T-Mobile Arena

- Boxing: MGM Grand Garden Arena

- Women's National Basketball Association: Las Vegas Aces at the Mandalay Bay Events Center

Golf

.JPG.webp)

In 2000, Bali Hai Golf Club opened just south of Mandalay Bay and the Strip.[75]

As land values on the Strip have increased over the years, the resort-affiliated golf courses been removed to make way for building projects.[76] The Tropicana Country Club closed in 1990[77] and the Dunes golf course in the mid-90s. Steve Wynn, founder of previously owned Mirage Resorts, purchased the Desert Inn and golf course for his new company Wynn Resorts and redeveloped the course as the Wynn Golf Club. This course closed in 2017, but the development planned for the course was cancelled and the course will be renovated and re-opened in late 2019.[78] The Aladdin also had a nine-hole golf course in the 1960s.[79]

Amusement parks and rides

The Strip is home to the Adventuredome indoor amusement park, and the Stratosphere tower has several rides:

Other rides on the Strip include:

- The Roller Coaster (also known as Big Apple Coaster)

- High Roller

- Fly Linq

Sustainability

Although the Strip has elaborate displays, fountains, and large buffet restaurants, many of the hotel resort properties are renowned for their sustainability efforts, including:[81][82]

- Water conservation:Approaches include reclaiming water and placing it back into Lake Mead, using minimal outdoor landscaping, upgrading toilets, using low-flow showerheads, and setting goals for water conservation.

- Recycling:In 2017, the recycling rate in Clark County was about 20%, while the recycling rate for major hotels on the Strip was about 40%.

- Food handing: Leftover food is composted or sent to agricultural farms. Untouched, undisturbed food is donated to local food banks.

- Energy efficiency: Hotels have updated appliances in rooms, installed LED lighting, and installed wireless lighting control systems.

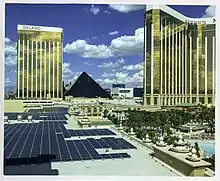

Renewable energy is generated and used on the Strip.[81] MGM initiated solar power when it built a solar array on top of the Mandalay Bay in 2014 and expanded it in 2016 .[81][83] The solar array at the Mandalay Bay, a 28-acre system capable of powering 1,300 homes, is one of the largest commercial rooftop solar arrays in the United States.[84] The solar array includes more than 26,000 solar panels capable of providing a total of 8.3 megawatts DC (6.5 megawatts AC), sufficient for powering 25% of the Mandalay Bay campus.[85]

Energy-efficient buildings are also been implemented and the Strip has one of the highest concentrations of LEED-certified buildings in the world.[81][86] Some examples of LEED-certified buildings are the Octavius Tower at Caesars Palace and the Linq Promenade, both of which are certified LEED Silver.[81]

Locations of major landmarks

Current landmarks

Former hotel/casino locations

| North towards Fremont Street

↑ | ||

| Vegas World/Million Dollar Casino | Las Vegas Boulevard | |

| Jackpot Casino/Money Tree Casino | Holy Cow/Foxy's Firehouse | |

| Sahara Avenue | Sahara Avenue | |

| El Rancho Vegas | Club Bingo/SLS | |

| Wet 'n Wild | ||

| Thunderbird/Silverbird/El Rancho, Algiers Hotel | ||

| Riviera | ||

| Westward Ho | La Concha Motel | |

| Silver City/Riata | ||

| Stardust/Royal Nevada | ||

| Desert Inn Road | Desert Inn Road | |

| Silver Slipper/Golden Slipper | ||

| New Frontier/Last Frontier/Frontier | Desert Inn | |

| Spring Mountain Road | Sands Avenue | |

| Sands | ||

| Castaways | Nob Hill Casino | |

| Holiday Casino, Holiday Inn | ||

| Flamingo Capri/Imperial Palace/Quad | ||

| O'Sheas Casino | ||

| Barbary Coast/Bill's | ||

| Flamingo Road | Flamingo Road | |

| Dunes | MGM Grand | |

| Aladdin/Tallyho/King's Crown | ||

| Boardwalk/Mandarin Oriental | ||

| Monte Carlo | Harmon Avenue | |

| Marina | ||

| Tropicana Avenue | Tropicana Avenue | |

| Hacienda | ||

| Russell Road | Glass Pool Inn | |

| Klondike/Kona Kai | ||

| ↓

South towards Interstate 215 | ||

Demolished or closed Strip casinos and hotels

- Aladdin: Opened in 1962 as the Tallyho, became the King's Crown Tallyho in 1963, the Aladdin in 1966, and was demolished in 1998. A new Aladdin resort opened on the property in 2000, and was renamed Planet Hollywood in 2007.

- Big Red's Casino: Opened in 1981 and closed in 1982. Property developed for CBS Sports World Casino in 1997. Changed name to Sports World Casino after CBS threatened to sue.[87] Closed in 2001, now a shopping center.

- Barbary Coast Hotel and Casino: Closed in 2007, now The Cromwell.

- Boardwalk Hotel and Casino: Closed on January 6, 2006, demolished May 9, 2006 to make way for CityCenter.

- Castaways Hotel and Casino: Opened in 1957 as the San Souci Hotel and became the Castaways in 1963 and was demolished in 1987. Now The Mirage.

- Desert Inn: Closed on August 28, 2000, demolished in 2004, now Wynn Las Vegas and Encore Las Vegas; Desert Inn golf course was retained and improved.

- Dunes Hotel and Casino: Closed on January 26, 1993, demolished in 1993, now Bellagio. The Dunes golf course is now occupied by parts of Park MGM, New York-New York, CityCenter, Cosmopolitan, and T-Mobile Arena.

- El Rancho (formerly Thunderbird/Silverbird): Closed in 1992 and demolished in 2000. Now the unfinished The Drew Las Vegas.

- El Rancho Vegas: Burned down in 1960. The Hilton Grand Vacations Club timeshare now exists on the south edge of the site where the resort once stood; the remainder is now the Las Vegas Festival Grounds.

- Hacienda: Closed and demolished in 1996, now Mandalay Bay. Until 2015, a separate Hacienda operated outside Boulder City, formerly the Gold Strike Inn.

- Holy Cow Casino and Brewery: First micro brewery in Las Vegas. Closed in 2002, now a Walgreens store.

- Jackpot Casino: Closed in 1977, now part of Bonanza Gift Shop

- Klondike Hotel and Casino: Closed in 2006, demolished in 2008.

- Little Caesars Casino: Opened in 1970 and closed in 1994. Paris Las Vegas now occupies the area.[88]

- Money Tree Casino: Closed in 1979, now Bonanza Gift Shop.

- Marina Hotel and Casino: Closed, adapted into MGM Grand, now the West Wing of the MGM Grand.

- New Frontier: Closed July 16, 2007, demolished November 13, 2007. Currently being redeveloped as Wynn West.

- Nob Hill Casino: Opened in 1979 and closed in 1990. Now Casino Royale

- Riviera Hotel and Casino: Opened in 1955; Closed in May 2015 to make way for the Las Vegas Global Business District.

- Royal Nevada: Opened in 1955; became part of the Stardust in 1959.

- Sands Hotel and Casino: Closed on June 30, 1996, demolished in 1996, now The Venetian.

- Silver City Casino: Closed in 1999, now the Silver City Plaza Shopping Center.

- Silver Slipper Casino: Opened in 1950 and closed and demolished in 1988. It became the parking lot for the New Frontier until its closure and demolition in 2007.

- Stardust Resort and Casino: Closed on November 1, 2006, demolished on March 13, 2007. Currently being redeveloped as Resorts World Las Vegas.

- Vegas World: Opened in 1979 and closed in 1995. Now The Strat

- Westward Ho Hotel and Casino: Closed in 2005, demolished in 2006.

Gallery

The iconic Welcome to Las Vegas sign was built in 1959.

The iconic Welcome to Las Vegas sign was built in 1959. The Strip in 2009.

The Strip in 2009. A view of the southern end of the Strip. Looking northward from Tropicana Avenue.

A view of the southern end of the Strip. Looking northward from Tropicana Avenue. View of the Strip from the Eiffel Tower of the Paris Las Vegas.

View of the Strip from the Eiffel Tower of the Paris Las Vegas. Photo taken May 21, 2010, a view of the Strip from the Renaissance Hotel.

Photo taken May 21, 2010, a view of the Strip from the Renaissance Hotel. View of Monte Carlo Resort and Casino with City Center in the background

View of Monte Carlo Resort and Casino with City Center in the background The Bellagio Fountains as seen from the hotel

The Bellagio Fountains as seen from the hotel The Cosmopolitan

The Cosmopolitan The Las Vegas High Roller is the tallest Ferris wheel in the world

The Las Vegas High Roller is the tallest Ferris wheel in the world.jpg.webp) Wynn Las Vegas

Wynn Las Vegas

References

- Google (October 17, 2020). "Overview of the Las Vegas Strip" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Lukas, Scott A. (2007). "Theming as a Sensory Phenomenon: Discovering the Senses on the Las Vegas Strip". In Scott A. Lukas (ed.). The Themed Space: Locating Culture, Nation, and Self. Lexington Books. pp. 75–95. ISBN 978-0-7391-2142-9.

- "U.S. Transportation Deputy Secretary Downey Announces New All-American Roads, National Scenic Byways in 20 States" (Press release). Federal Highway Administration. June 15, 2000. Retrieved June 22, 2008.; "Las Vegas Strip Named All-American Road" (Press release). Archived from the original on June 12, 2006. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- "Scenic Byways | Nevada Department of Transportation". www.nevadadot.com. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- "Knowing Vegas: Why isn't the Strip in Las Vegas?". Las Vegas Review-Journal. August 3, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- "The Shocking Truth About the Las Vegas Strip". www.mentalfloss.com. May 17, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Amanda Finnegan (May 21, 2009). "'Fabulous' sign garners historic designation – Las Vegas Sun Newspaper". lasvegassun.com. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Joe Schoenmann (February 3, 2010). "Vegas not alone in wanting in on .vegas". Las Vegas Sun.

- "County Turns 100 July 1, Dubbed 'Centennial Day'" (Press release). Clark County, Nevada. June 23, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- "Even in a city built on illusion, the Stratosphere is having a tough time proving it's on the Vegas Strip". Los Angeles Times. December 14, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Miller, Cody (July 3, 2019). "Newly rebranded Strip resort's slogan sparks Las Vegas debate". KSNV. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- "Debating the Stratosphere's Strip-ness is like trying to define Las Vegas – Las Vegas Weekly". lasvegasweekly.com. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- "Is the Stratosphere on the Las Vegas Strip? Owner, County Disagree".

- Newton, Michael (2009). Mr. Mob: The Life and Crimes of Moe Dalitz. McFarland. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9780786453627.

- Rothman, Hal (2003). Neon metropolis: how Las Vegas started the twenty-first century. Routledge. p. 16. ISBN 9780415926133.

- "Las Vegas: An Unconventional History". American Experience. PBS. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- Moehring, Eugene P. (2000). Resort City in the Sunbelt: Las Vegas, 1930–2000. University of Nevada Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-87417-356-6.

- "New town 'richest' in state". Las Vegas Review-Journal. August 21, 1951. p. 1.

- "Rich new Nevada town of Winchester founded". Reno Gazette-Journal. October 8, 1953 – via Newspapers.com.

- Michael Mishak (May 24, 2009). "Why consolidating city and county governments isn't a silver bullet for waste". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- "Lights to Dim On Vegas Strip in Memory of Entertainer With AM-Sammy Davis Jr". Associated Press. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- "UNLV honors Jerry Tarkanian". ESPN. Associated Press. February 19, 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- "Strip Lights Dimmed In Fitting Tribute To Rickles". Norm.Vegas. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- Apgar, Blake (October 9, 2017). "Watch the Las Vegas Strip marquees go dark". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- "Treasure Island Show Symbolizes New Era for Strip Resort" (Press release). Archived from the original on August 8, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- Barboza, David (January 24, 2007). "Asian Rival Moves Past Las Vegas". The New York Times.

- Hernandez, Dan; McCarthy, Tom; McGowan, Michael (October 2, 2017). "Mandalay Bay attack: at least 50 killed in America's deadliest mass shooting". The Guardian. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- Lacanlale, Rio (August 24, 2020). "California woman declared 59th victim of 2017 massacre in Las Vegas". The Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- Lacanlale, Rio (September 17, 2020). "Las Vegas woman becomes 60th victim of October 2017 mass shooting". The Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- "Monte Carlo officially transitions to new brand — Park MGM". Las Vegas Review-Journal. May 10, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- "SLS to officially make change to Sahara Las Vegas on Thursday". Las Vegas Review-Journal. August 28, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- "Resorts World updates plans, opening of $4.3B Las Vegas Strip resort". Las Vegas Review-Journal. November 21, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- Segall, Eli (March 16, 2019). "Las Vegas Strip motel may make way for 620-room hotel-casino". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- Segall, Eli (February 18, 2020). "California developer plans luxury hotel on south Strip". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- Seeman, Matthew (February 18, 2020). "Luxury 21-story hotel announced for vacant lot on Las Vegas Strip". KSNV. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- "Opening of Drew Las Vegas pushed back until 2022". Las Vegas Review-Journal. April 16, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- Gillan, Jeff (June 7, 2019). "Robinson says massive All Net Resort and Arena on Las Vegas Strip 'still on'". KSNV. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- Horwath, Bryan (August 14, 2020). "Work resumes at MSG Sphere site on Strip, company says – VEGAS INC". vegasinc.lasvegassun.com. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- "Buses in Las Vegas". www.vegas.com. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- "Las Vegas Monorails". VEGAS.com. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- Garcia, Oskar (March 11, 2011). "Frugal travel: Vegas offers fun at low stakes". San Jose Mercury News. Associated Press. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- "Las Vegas Monorail Map // See the Official Monorail Route Map". Las Vegas Monorail. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- "Pedestrian Movement in the Resort Corridor" (PDF).

- Miller, Cody (December 21, 2019). "Latest pedestrian bridge over the Strip to open before Christmas". KSNV. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- "Las Vegas Pedestrian Bridges – 1996 Awards – Excellence in Highway Design – Geometric Design – Design – Federal Highway Administration". www.fhwa.dot.gov. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Santos, Renee (August 20, 2019). "County adding 17th pedestrian bridge on the strip, soon another near Bellagio". KSNV. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Nordahl, Darrin (2002). The Architecture of Mobility: Enhancing the Urban Experience Along the Las Vegas Strip. University of California, Berkeley.

- HowTo, Las Vegas. "Walking on the Las Vegas Strip". lasvegashowto.com. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- "Walking on the Las Vegas Strip". lasvegashowto.com. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- "Pedestrians complain about long walks to crosswalks". Las Vegas Review-Journal. January 27, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- "Hundreds of Bollards Along Las Vegas Strip to Be Shortened".

- "Clark County cutting down bollards on the Las Vegas Strip". KTNV. October 3, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- "Hundreds of bollards along Las Vegas Strip to be shortened". KSNV. Associated Press. October 11, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- "Clark County Pedestrian Study: Las Vegas Boulevard- Russell Road to Sahara Avenue" (PDF).

- "Clark County Pedestrian Study: Las Vegas Boulevard-Russell Road to Sahara Avenue: 2015 Update" (PDF).

- "Taxis in Las Vegas". www.vegas.com. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- "Taxicab Authority". taxi.nv.gov. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- Reed, C. Moon (June 1, 2019). "Comparing the many rideshare options in Las Vegas – Las Vegas Sun Newspaper". lasvegassun.com. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority. "2019 Las Vegas Visitor Profile Study" (PDF). Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- UNLV Center for Gaming Research. "Trends for Big Las Vegas Strip Casinos, 2012–2019" (PDF).

- "Las Vegas Strip Table Mix, The Evolution of Casino Games, 1985–2019" (PDF).

- "Circa upping the ante for sportsbooks". Las Vegas Review-Journal. October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- Stapleton, Susan (September 2, 2020). "Treasure Island Is Off to the Races With Its New Sportsbook Debuting on the Strip". Eater Vegas. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- "ESPN To Air Sports Betting Content From New Las Vegas Studio At LINQ Hotel In Las Vegas". SportsHandle. August 24, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Murphy, Chris (October 23, 2020). "Caesars to reopen The Cromwell and debut William Hill sportsbook". SBC Americas. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- "Las Vegas Nightclubs". Las Vegas Nightclubs. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- Glusac, Elaine (September 14, 2007). "The Unlikely All-Ages Appeal of Las Vegas". The New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- "The 25 Greatest Headliners in Las Vegas History". Las Vegas Weekly. December 13, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Showcase Theater". Fandango.com. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- Millward, Wade Tyler (January 24, 2018). "Las Vegas Strip's only movie theater closes". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- "2019 Las Vegas Visitor Profile Study" (PDF). Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- Hubble Smith (September 30, 2011). "Portion of Showcase mall sold for $93.5 million". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- "New York-New York, Monte Carlo To Be Transformed Into Park-Like District". VegasChatter. April 18, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- "Sports in Las Vegas". www.vegas.com. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- Moran, Craig (August 2, 2010). "Money-losing golf club may become industrial park". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- "Wynn Golf Club in Las Vegas set to close Dec. 17". Golf Advisor. August 28, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- "Log in to NewsBank". infoweb.newsbank.com.

- Akers, Mick (November 7, 2018). "Wynn scraps lagoon project, will reopen golf course". Las Vegas Sun.

- "Las Vegas Nevada~Milton Prell's Aladdin Hotel~Golf Course & Country Club~1969 Pc".

- "Topgolf will develop multimillion-dollar, three-level center in Overland Park". Bizjournals.com. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- Miranda Willson (April 21, 2019). "Sustainability on the Strip: Behind the glitz and glamorous excess, properties are serious about being green – Las Vegas Sun Newspaper". lasvegassun.com. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- "Energy Department Recognizes Las Vegas Sands Corporation for Energy- and Water-Efficiency Upgrades". Energy.gov. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- "Mandalay Bay Bets on the Sun With Nation's Largest Solar Rooftop". Solar Reviews. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- "Las Vegas shines as a model for solar power". Christian Science Monitor. October 27, 2017. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- "Mandalay Bay Resort & Casino Offsets 25 Percent of Energy Demand with Rooftop Solar Panels". Hospitality Technology. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Walshe, Sadhbh (April 25, 2013). "Las Vegas: the reinvention of Sin City as a sustainable city". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Geer, Carri (May 25, 1998). "CBS Broadcasting, casino settle in trademark dispute". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- "Las Vegas Little Caesar's Casino Chips including the Sports Book Chips". Oldvegaschips.com. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Las Vegas Strip. |

- Schmid, H. (2009), Economy of Fascination: Dubai and Las Vegas as Themed Urban Landscapes, Stuttgart; Berlin: E. Schweizerbart Science Publishers, ISBN 978-3-443-37014-5

.jpg.webp)