Diego de Torres y Moyachoque

Diego de Torre(s) y Moyachoque (1549 in Tunja, New Kingdom of Granada – 4 April 1590 in Madrid, Spain) was cacique of Turmequé, in the former Muisca Confederation, under Spanish rule. He served as chief from 1571 to his death. De Torres y Moyachoque was a mestizo, the child of a Spanish conquistador and a Muisca mother. He is known for his defense of the local Muisca and resistance against the Spanish encomenderos, particularly his half-brother Pedro de Torres. De Torres y Moyachoque is also known as the first cartographer of the lands surrounding the capital of the New Kingdom of Granada, Santa Fe de Bogotá.

Diego de Torres y Moyachoque | |

|---|---|

| cacique | |

| Reign | 1571–1590 |

| Predecessor | Maternal uncle; Moyachoque |

| Born | 1549 Tunja, New Kingdom of Granada |

| Died | 4 April 1590 (aged 40–41) Madrid, Spain |

| Queen | Juana de Oropesa |

| Issue

Beatriz de Torre(s) y Moyachoque (sister) Pedro de Torre(s) (half-brother) María de Herrezuelo (half-sister) | |

| Father | Juan de Torre(s) |

| Mother | Catalina Moyachoque |

| Memorials | Main square of Turmequé |

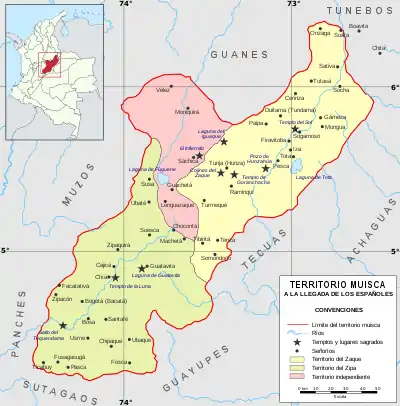

Turmequé is situated in the centre, in the yellow (former zaque rule) part

De Torres y Moyachoque traveled twice to Spain, first in 1575-1577 and the second journey in the 1580s, where he presented complaints about the mistreatment of the Muisca by the Spanish colonisers to the Spanish King Felipe II. After this travel, he stayed, married, and died in Madrid on April 4, 1590.

Biography

Diego de Torres y Moyachoque was born in the city of Tunja, former capital of the central Muisca Confederation called Hunza in 1549 from a Spanish conquistador, Juan de Torre(s) and the eldest sister of the previous cacique whose name is unknown, Catalina Moyachoque.[1] Catalina was approximately 12 years old when she gave birth to Diego de Torres y Moyachoque.[2] He had one sister Beatriz, a half-sister María and a half-brother Pedro de Torre.[3] Beatriz was partner of the former priest of Vélez, Santander, Francisco Sánchez Herreño, to whom she bore a daughter: Francisca González de la Nava y Herreño.[4]

He studied at the school for mestizo children of conquistadors set up by Diego de Aquila and later at the Dominican Convent (Convento de los Dominicos) in Tunja, where he was educated in grammar, religion, moral and law. The cacique was also trained in horse-riding and an excellent archer.[1]

De Torres y Moyachoque inherited the cacicazgo at age 21/22 in 1571, when his uncle, the former cacique, died.[5] He referred to himself as the cacique cristiano; (Catholic) Christian cacique.[6]

The Muisca Confederation was mostly conquered during the Spanish conquest of the Muisca from 1537 to 1540, and the town of Turmequé, at about 53 kilometres (33 mi) from Tunja, was submitted by main conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada on July 20, 1537.[7][8] In 1574, the cacique of Turmequé had a dispute with the encomendero of the town, his half-brother Pedro de Torres, son of Juan de Torres and his first Spanish wife Leonor Ruiz Herrezuelos.[9] The dispute was about the mistreatment of the indigenous people under the encomienda rules. The cacique of Tibasosa Alonso de Silva, also a mestizo, joined De Torres in his resistance.[5] De Torres y Moyachoque traveled from Cartagena in the New Kingdom of Granada to Spain in 1575 to hand over to the King of Spain a series of demands for the rights of the indigenous people of Turmequé.[8] He stranded in Santo Domingo, the capital of the Caribbean and stayed there for almost three years, studying the works of Bartolomé de las Casas, before traveling on to Madrid, where he arrived in 1577.[5]

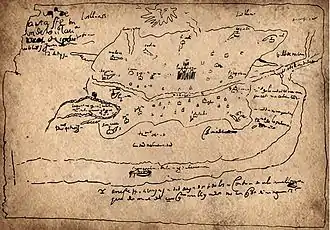

In Spain, De Torres y Moyachoque befriended Juan Bautista de Monzón and both traveled back to South America, De Monzón being the new visitador of the colony.[5] Here, the Spanish colonisers immediately accused both men to work against the Spanish Crown and convicted De Torres y Moyachoque to death. He promptly fled into the mountains of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, but later returned to Turmequé. In 1578, he made the first map of the Bogotá savanna, including Santa Fe de Bogotá and surrounding settlements, the Bogotá River and Sué rising over the Llanos Orientales.[10]

In the meantime, in 1581, a new visitador had arrived with his delegation from Spain, Juan Prieto de Orellana. Diego de Torres presented himself to the new Spanish rulers and was sent again to Spain. There, he presented his Memoria de los Agravios about the mistreatments of the Muisca to the Spanish King Felipe II in 1584.[11] At these encounters, De Torres y Moyachoque was permitted to be seated instead of kneeling, which was common for visitors to the Spanish King.[12] He was acquitted of the charges, married Juana de Oropesa, and died in the capital of the Spanish kingdom on April 4, 1590 at age 40.[5][10]

El Carnero

The story about Diego de Torres y Moyachoque has been told by Juan Rodríguez Freyle in his famous work El Carnero in 1636, albeit in a different manner. In this book, Rodríguez Freyle, attributed all the conflicts to jealousy over the indigenous women and De Torres y Moyachoque plays a minor part in the story about adultery and corruption.[5][13]

Legacy

Although he is commonly viewed as a mestizo who was highly hispanised,[14] De Torres y Moyachoque is considered one of the most important Colombian people of the 16th century and in Turmequé a monument honouring the Muisca has been constructed.[7][10]

References

- (in Spanish) Diego de Torres y Moyachoque, cacique de Turmequé

- Catalina Moyachoque - Geni

- Diego de Torre y Moyachoque - Geni

- Beatriz de Torre y Moyachoque - Geni

- (in Spanish) El levantamiento del Cacique de Turmequé - Banco de la República

- Restrepo, 2010, p.21

- (in Spanish) Official website Turmequé Archived 2016-01-12 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) El legado del cacique Turmequé - El Espectador

- Pedro de Torre - Geni

- (in Spanish) Personajes - Diego de Torres y Moyachoque

- Restrepo, 2010, p.16

- Restrepo, 2010, p.31

- Restrepo, 2010, p.26

- Restrepo, 2010, p.19

Bibliography

- Restrepo, Luis Fernando. 2010. El cacique de Turmequé o los agravios de la memoria - The cacique de Turmequé or the affronts of memory. Cuadernos de Literatura 14. 14-33. Accessed 2016-11-04.