Muisca Confederation

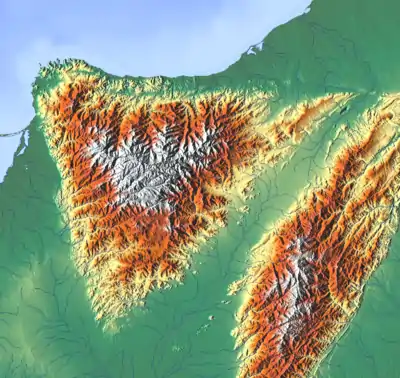

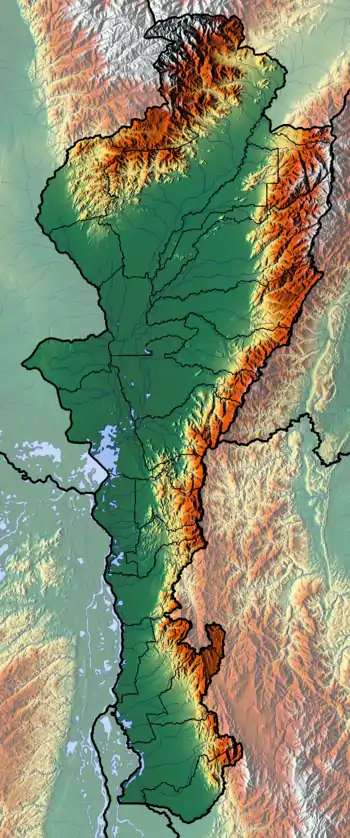

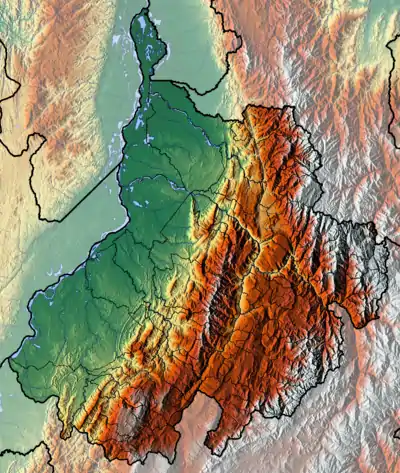

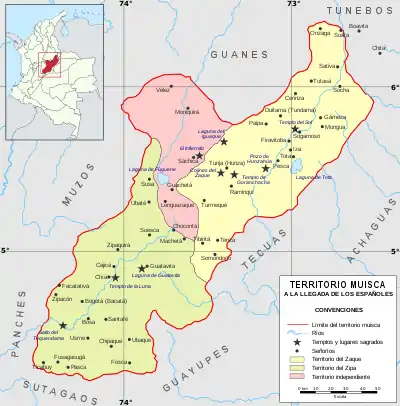

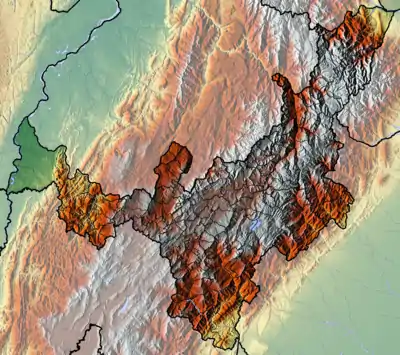

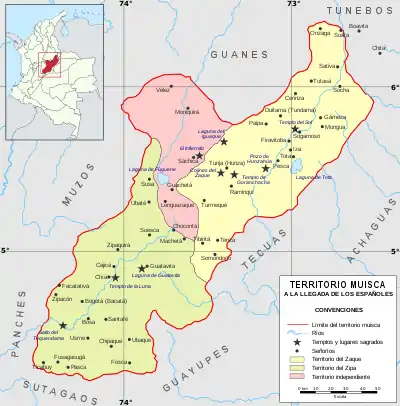

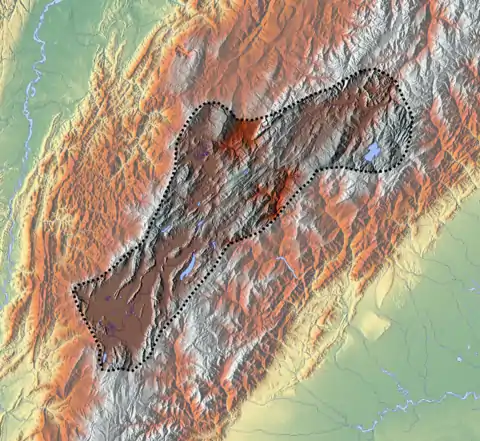

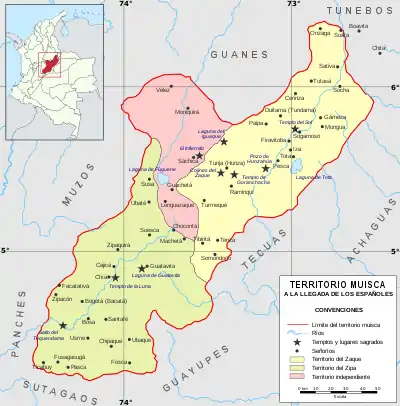

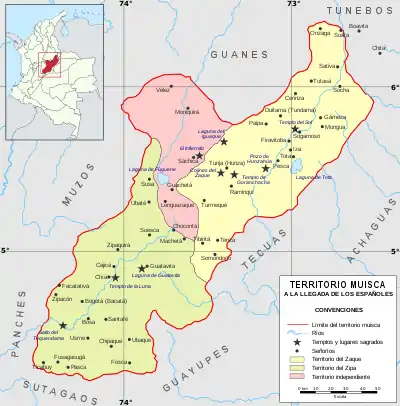

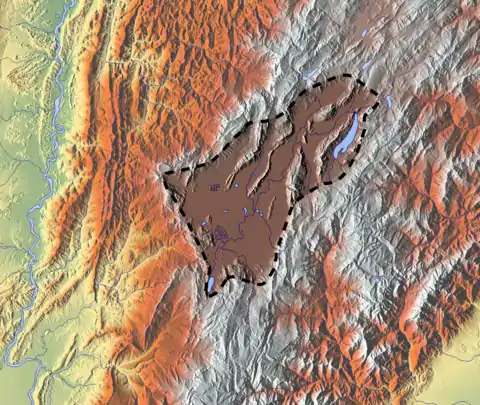

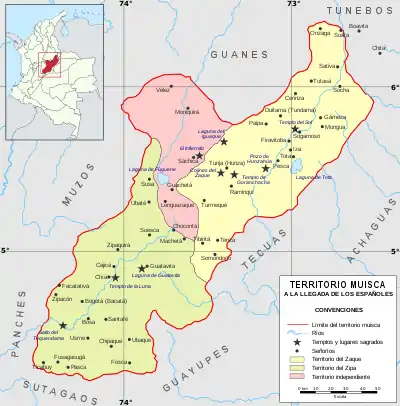

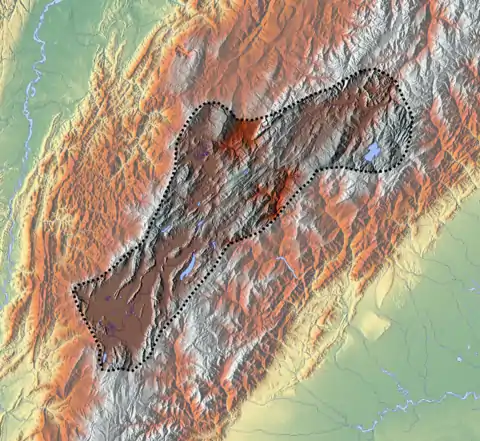

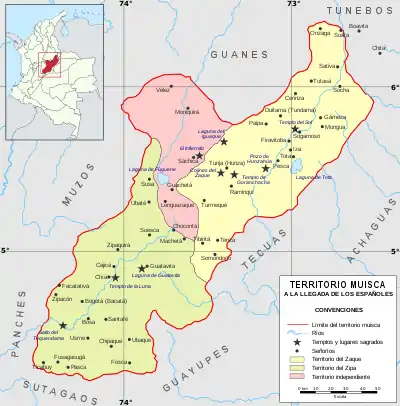

The Muisca Confederation was a loose confederation of different Muisca rulers (zaques, zipas, iraca and tundama) in the central Andean highlands of present-day Colombia before the Spanish conquest of northern South America. The area, presently called Altiplano Cundiboyacense, comprised the current departments of Boyacá, Cundinamarca and minor parts of Santander with a total surface area of approximately 25,000 square kilometres (9,700 sq mi).[note 1]

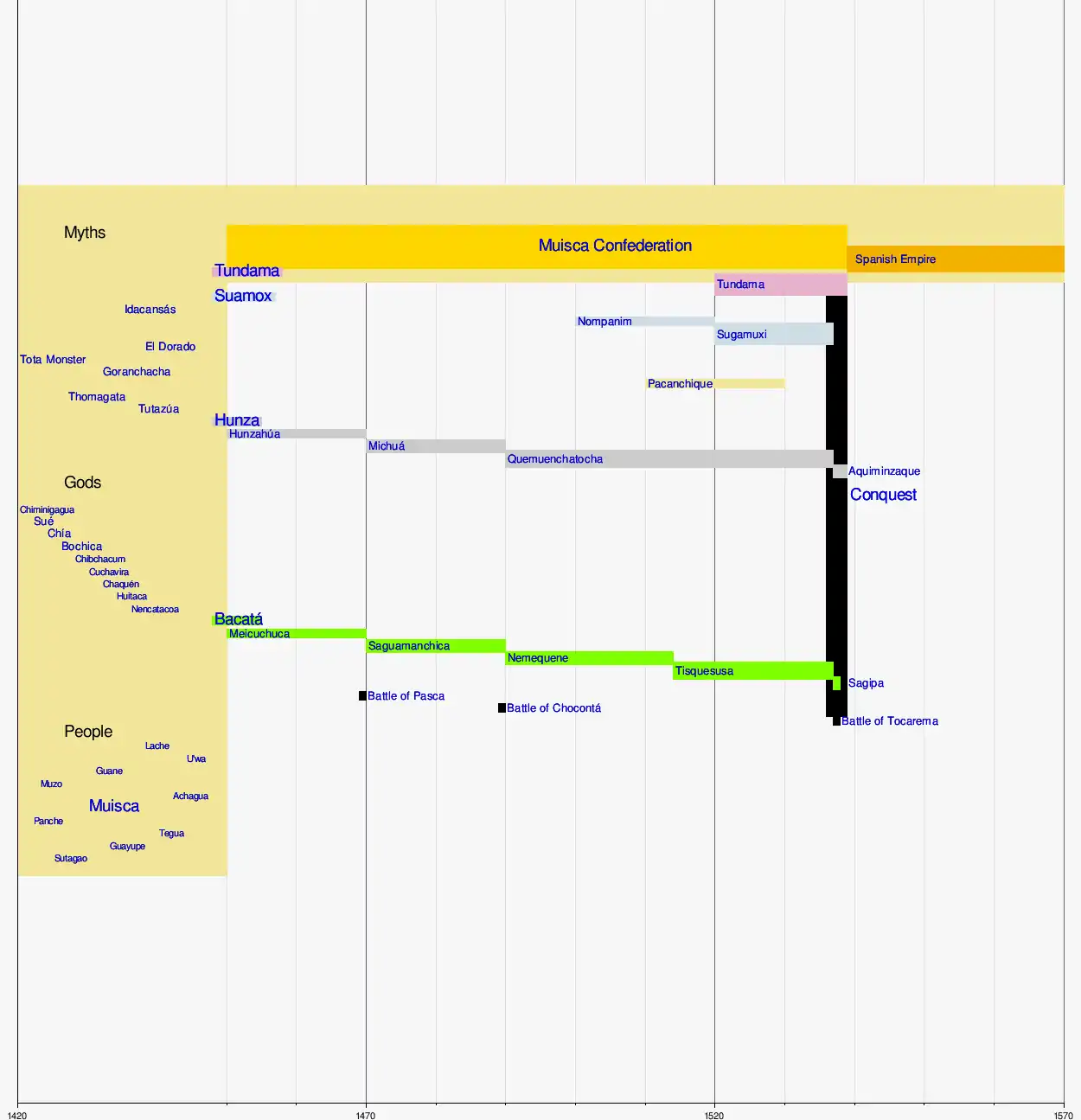

Muisca Confederation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~1450–1540 | |||||||||

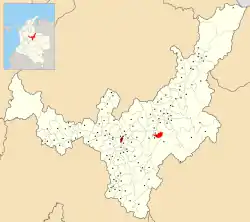

Muisca Confederation on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense Zaque rule in yellow Zipa rule in green Independent territories in red | |||||||||

| Capital | Hunza and Bacatá (~1450–1540) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Muysccubun | ||||||||

| Religion | Muisca religion | ||||||||

| Zaque and zipa | |||||||||

• ~1450–1470 | zaque Hunzahúa zipa Meicuchuca | ||||||||

• 1470–1490 | zaque Saguamanchica zipa Michuá | ||||||||

• 1490–1537 1490–1514 | zaque Quemuenchatocha zipa Nemequene | ||||||||

• 1514–1537 | zipa Tisquesusa | ||||||||

• 1537–1540 1537–1539 | zaque Aquiminzaque zipa Sagipa | ||||||||

| Historical era | Pre-Columbian | ||||||||

• Established | ~1450 | ||||||||

| March 1537 | |||||||||

| 20 April 1537 | |||||||||

• Conquest of Hunza | 20 August 1537 | ||||||||

• Destruction of the Sun Temple | September 1537 | ||||||||

| 6 August 1538 20 August 1538 | |||||||||

| 6 August 1539 December 1539 | |||||||||

| 1540 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 25,000 km2 (9,700 sq mi) | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• | ~2,000,000 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Colombia - Cundinamarca - Boyacá - Santander | ||||||||

According to some Muisca scholars the Muisca Confederation was one of the best-organized confederations of tribes on the South American continent.[2] Modern anthropologists, such as Jorge Gamboa Mendoza, attribute the present-day knowledge about the confederation and its organization more to a reflection by Spanish chroniclers who predominantly wrote about it a century or more after the Muisca were conquered and proposed the idea of a loose collection of different people with slightly different languages and backgrounds.[3]

Geography

Climate

| Climate charts for the extremes and four most important settlements of the Muisca Confederation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

.png.webp) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The climates (Af-Cfb-Cwb) of the geographic (NW, NE, SW and SE) and topographic extremes and for the four main settlements of the Muisca Confederation situated on the Altiplano, from SW to NE; Bacatá, Hunza, Suamox and Tundama are rather constant over the year with wetter periods in April–May and October–November | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Muisca Confederation

In the times before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca, the central part of present-day Colombia; the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes was inhabited by the Muisca people who were organised in a loose confederation of rulers. The central authorities of Bacatá in the south and Hunza in the north were called zipa and zaque respectively. Other rulers were the iraca priest in sacred City of the Sun Sugamuxi, the Tundama of Tundama and various other caciques (chiefs). The Muisca spoke Chibcha, in their own language called Muysccubun; "language of the people".

The Muisca people, different from the other three great civilisations of the Americas; the Maya, Aztec and Inca, did not build grand stone architecture. Their settlements were relatively small and consisted of bohíos; circular houses of wood and clay, organised around a central market square with the house of the cacique in the centre. Roads were present to connect the settlements with each other and with the surrounding indigenous groups, of which the Guane and Lache to the north, the Panche and Muzo to the west and Guayupe, Achagua and Tegua to the east were the most important.

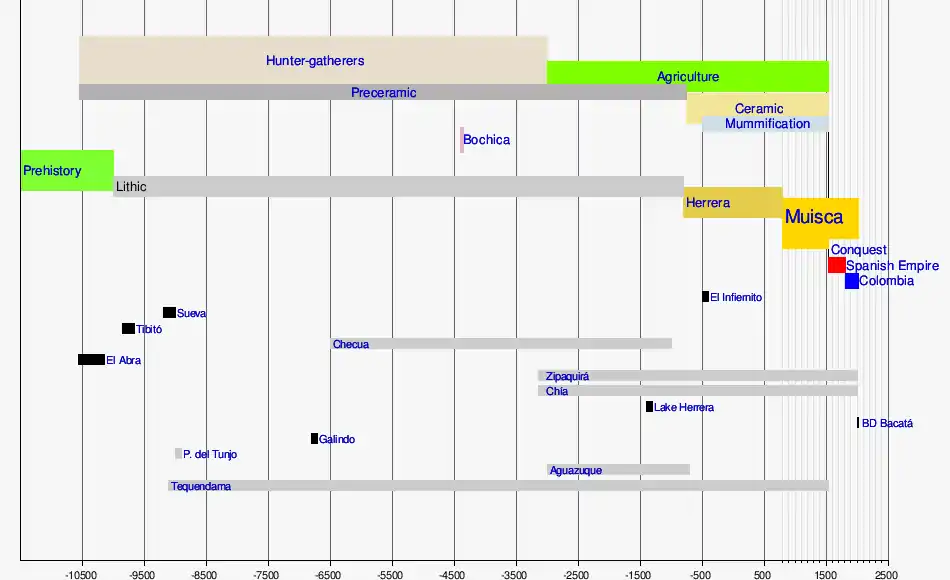

Prehistory

Early Amerindian settlers led a hunter-gatherer life among still extant megafauna living in cool habitats around Pleistocene lakes, of which the humedales in Bogotá, Lake Suesca, Lake Fúquene and Lake Herrera are notable examples. Multiple evidences of late Pleistocene to middle Holocene population of the Bogotá savanna, the high plateau in the Colombian Andes, have been found to date. As is common with caves and rock shelters, Tequendama was inhabited from around 11,000 years BP, and continuing into the prehistorical, Herrera and Muisca periods, making it the oldest site of Colombia, together with El Abra (12,500 BP), located north of Zipaquirá and Tibitó, located within the boundaries of Tocancipá (11,740 BP).[4][5] The oldest human remains and the oldest complete skeleton were discovered at Tequendama and has been named "Hombre del Tequendama" or Homo Tequendama. Other artefacts have been found in Gachalá (9100 BP), Sueva (Junín) and Zipacón.[6] Just west of the Altiplano, the oldest archaeological remains were found; in Pubenza, part of Tocaima and have been dated at 16,000 years Before Present.[7]

Pre-Columbian era

| Timeline of inhabitation of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia | |

|

.png.webp) |

Herrera Period

| Period name |

Start age |

End age |

|---|---|---|

| Herrera | 800 BCE | 800 |

| Early Muisca | 800 | 1200 |

| Late Muisca | 1200 | 1537 |

| Kruschek, 2003[8] | ||

The Herrera Period is a phase in the history of Colombia. It is part of the Andean preceramic and ceramic, time equivalent of the North American pre-Columbian formative and classic stages and age dated by various archaeologists.[9] The Herrera Period predates the age of the Muisca people, who inhabited the Altiplano Cundiboyacense before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca and postdates the lithic formative stage and prehistory of the eastern Andean region in Colombia. The Herrera Period is usually defined as ranging from 800 BCE to 800 AD,[10] although some scholars date it as early as 1500 BCE.[11]

Ample evidence of the Herrera Period has been uncovered on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense and main archaeologists contributing to the present knowledge about the Herrera Period are scholars Ana María Groot, Gonzalo Correal Urrego, Thomas van der Hammen, Carl Henrik Langebaek Rueda, Sylvia M. Broadbent, Marianne Cardale de Schrimpff and others.

Muisca

|

| Part of a series on |

| Muisca culture |

|---|

| Topics |

| Geography |

| The Salt People |

| Main neighbours |

| History and timeline |

The Muisca were polytheistic and their religion and mythology was closely connected with the natural area they were inhabiting. They had a thorough understanding of astronomical parameters and developed a complex luni-solar calendar; the Muisca calendar. According to the calendar they had specific times for sowing, harvest and the organisation of festivals where they sang, danced and played music and drank their national drink chicha in great quantities.

The most respected members of the community were mummified and the mummies were not buried, yet displayed in their temples, in natural locations such as caves and even carried on their backs during warfare to impress their enemies.

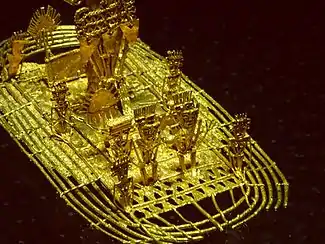

Their art is the most famous remnant of their culture, as living spaces, temples and other existing structures have been destroyed by the Spanish who colonised the Muisca territories. A primary example of their fine goldworking is the Muisca raft, together with more objects made of gold, tumbaga, ceramics and cotton displayed in the Museo del Oro in Bogotá, the ancient capital of the southern Muisca.

The Muisca were a predominantly agricultural society with small-scale farmfields, part of more extensive terrains. To diversify their diet, they traded mantles, gold, emeralds and salt for fruits, vegetables, coca, yopo and cotton cultivated in lower altitude warmer terrains populated by their neighbours, the Muzo, Panche, Yarigui, Guane, Guayupe, Achagua, Tegua, Lache, Sutagao and U'wa. Trade of products grown farther away happened with the Calima, Pijao and Caribbean coastal communities around the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

The Muisca economy was self-sufficient regarding the basic supplies, thanks to the advanced technologies of the agriculture on raised terraces by the people. The system of trade was well established providing both the higher social classes and the general population abundances of gold, feathers, marine snails, coca, yopo and other luxury goods. Markets were held every four to eight days in various settlements throughout the Muisca Confederation and special markets were organised around festivities where merchants from far outside the Andes were trading their goods with the Muisca.

Apart from agriculture, the Muisca were well developed in the production of different crafts, using the raw materials traded with surrounding indigenous peoples. Famous are the golden and tumbaga objects made by the Muisca people. Cotton mantles, cloths and nets were made by the Muisca women and traded for valuable goods, tropical fruits and small cotton cloths were used as money. The Muisca were unique in South America for having real coins of gold, called tejuelos.

Mining was an important source of income for the Muisca, who were called "Salt People" because of their salt mines in Zipaquirá, Nemocón and Tausa. Like their western neighbours, the Muzo -who were called "The Emerald People"- they mined emeralds in their territories, mainly in Somondoco. Carbon was found throughout the region of the Muisca in Eocene sediments and used for the fires for cooking and the production of salt and golden ornaments.

The people used a decimal counting system and counted with their fingers. Their system went from 1 to 10 and for higher numerations they used the prefix quihicha or qhicha, which means "foot" in their Chibcha language Muysccubun. Eleven became thus "foot one", twelve "foot two", etc. As in the other pre-Columbian civilizations, the number 20 was special. It was the total number of all body extremities; fingers and toes. The Muisca used two forms to express twenty: "foot ten"; quihícha ubchihica or their exclusive word gueta, derived from gue, which means "house". Numbers between 20 and 30 were counted gueta asaqui ata ("twenty plus one"; 21), gueta asaqui ubchihica ("twenty plus ten"; 30). Larger numbers were counted as multiples of twenty; gue-bosa ("20 times 2"; 40), gue-hisca ("20 times 5"; 100). The Muisca script consisted of hieroglyphs, only used for numerals.[12]

Language

- Comparison of important words in various Chibchan languages

| Muysccubun | Notes | Uwa Boyacá N. de Santander Arauca |

Barí N. de Santander |

Chimila Cesar Magdalena |

Kogui S.N. de Santa Marta |

Kuna Darien Gap |

Guaymí Panama Costa Rica |

Boruca Costa Rica |

Maléku Costa Rica |

Rama Nicaragua |

English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chie | [13][14][15][16] | siʔ | chibai | má | saka | sö | sö | tebej | tlijii | tukan | Moon |

| ata | [17][18] | úbistia | intok | ti-tasu/nyé | kwati | éˇxi | dooka | one | |||

| muysca | [19][20] | dary | tsá | ngäbe | ochápaká | nkiikna | people/person/man | ||||

Territorial organization

| History of the Muisca | |||||||||

| |||||||||

.png.webp) Altiplano |

Muisca |

Art |

Architecture |

Astronomy |

Cuisine |

El Dorado |

Subsistence |

Women |

Conquest |

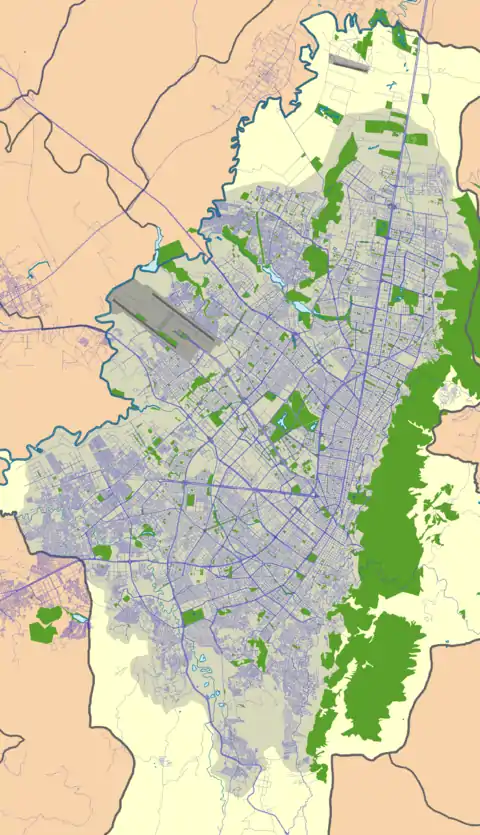

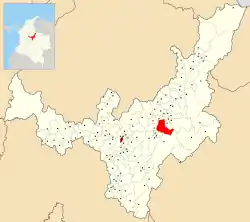

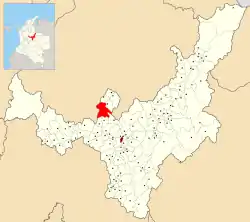

Bacatá

- Capital – Bacatá

- Area – 5,430 square kilometres (2,100 sq mi)

- Average elevation – 2,470 metres (8,100 ft)

- Last rulers – zipas Tisquesusa, Sagipa

- Date of conquest – 20 April 1537 (Funza) – Jiménez & Pérez de Quesada

- First city – 6 August 1538 (Bogotá) – Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada

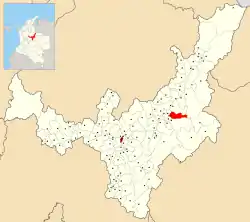

| Municipality | Department bold is capital |

Ruler(s) bold is seat |

Altitude urban centre (m) |

Surface area (km2) |

Remarks | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacatá | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2640 | 1587 | Muisca mummy found Important market town Petrographs found |

|

| Bojacá | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2598 | 109 | Lake Herrera Petrographs found |

|

| Cajicá | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2558 | 50.4 |  | |

| La Calera | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2718 | 317 | Petrographs found |  |

| Cáqueza | Cundinamarca | zipa | 1746 | 38 |  | |

| Chía | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2564 | 80 | Moon Temple Herrera site Petrographs found |

|

| Choachí | Cundinamarca | zipa | 1923 | 223 | Choachí Stone found |  |

| Chocontá | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2655 | 301.1 | Important market town Battle of Chocontá (~1490) Fortification between zipa & zaque |

|

| Cogua | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2600 | 113 | Muisca ceramics production Petrographs found |

|

| Cota | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2566 | 55 | Petrographs found Still Muisca people living |

|

| Cucunubá | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2590 | 112 | Petrographs found |  |

| Facatativá | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2586 | 158 | Piedras del Tunjo |  |

| Funza | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2548 | 70 | Important market town |  |

| Gachancipá | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2568 | 44 | Muisca mummy found Muisca ceramics production |

|

| Guasca | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2710 | 346 | Siecha Lakes Muisca ceramics production Petrographs found |

|

| Madrid | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2554 | 120.5 | Lake Herrera Petrographs found |

|

| Mosquera | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2516 | 107 | Lake Herrera Petrographs found |

|

| Nemocón | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2585 | 98.1 | Muisca salt mines Preceramic site Checua Petrographs found |

|

| Pacho | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2136 | 403.3 | Important market town |  |

| Pasca | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2180 | 246.24 | Battle of Pasca (~1470) Muisca raft found |

|

| El Rosal | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2685 | 86.48 |  | |

| San Antonio del Tequendama |

Cundinamarca | zipa | 1540 | 82 | Tequendama Falls Fortification against Panche Petrographs found |

|

| Sesquilé | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2595 | 141 | Lake Guatavita Minor Muisca salt mines |

|

| Sibaté | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2700 | 125.6 | Petrographs found |  |

| Soacha | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2565 | 184.45 | Preceramic site Tequendama Herrera site Muisca ceramics production Petrographs found |

|

| Sopó | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2650 | 111.5 | Herrera site |  |

| Subachoque | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2663 | 211.53 | Petrographs found |  |

| Suesca | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2584 | 177 | 150 Muisca mummies found Lake Suesca Muisca ceramics production Important market town Petrographs found |

|

| Sutatausa | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2550 | 67 | Petrographs found |  |

| Tabio | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2569 | 74.5 | Hot springs used by the Muisca |  |

| Tausa | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2931 | 204 | Muisca salt mines Petrographs found |

|

| Tena | Cundinamarca | zipa | 1384 | 55 | Fortification against Panche Petrographs found |

|

| Tenjo | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2587 | 108 | Petrographs found |  |

| Tibacuy | Cundinamarca | zipa & Panche | 1647 | 84.4 | Border with Panche Fortification against Panche & Sutagao Petrographs found |

|

| Tocancipá | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2605 | 73.51 | Preceramic site Tibitó Muisca ceramics production Important market town Petrographs found |

|

| Zipaquirá | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2650 | 197 | El Abra Muisca salt mines Important market town Petrographs and petroglyphs found |

|

| Fúquene | Cundinamarca | zipa zaque |

2750 | 90 | Lake Fúquene |  |

| Simijaca | Cundinamarca | zipa (1490–1537) | 2559 | 107 | Conquered by zipa Saguamanchica upon zaque Michuá (~1490) |

|

| Susa | Cundinamarca | zipa (1490–1537) | 2655 | 86 | Conquered by zipa Saguamanchica upon zaque Michuá (~1490) Lake Fúquene |

|

| Ubaté | Cundinamarca | zipa (1490–1537) | 2556 | 102 | Conquered by zipa Saguamanchica upon zaque Michuá (~1490) Muisca mummy found |

|

| Zipacón | Cundinamarca | zipa | 2550 | 70 | Agriculture Place of meditation for the zipa Petrographs found |

|

Chipazaque

| Municipality |

Department | Ruler(s) | Altitude (m) |

Surface area (km2) |

Remarks | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Junín | Cundinamarca | chipazaque | 2300 | 337 | Shared between zipa and zaque Petrographs found |

|

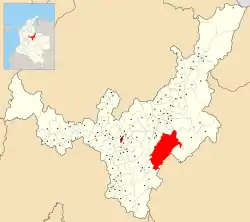

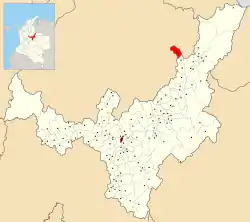

Hunza

- Capital – Hunza

- Area – 4,700 square kilometres (1,800 sq mi)

- Average elevation – 2,270 metres (7,450 ft)

- Last rulers – zaques Quemuenchatocha, Aquiminzaque

- Date of conquest – 20 August 1537 (Hunza) – Jiménez & Pérez de Quesada

- First city – 6 August 1539 (Tunja) – Gonzalo Suárez Rendón

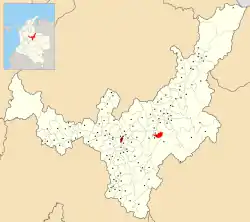

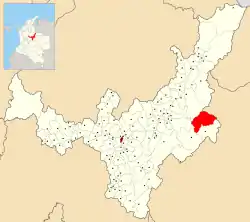

Iraca

- Capital – Suamox

- Area – 4,163 square kilometres (1,607 sq mi)

- Average elevation – 2,630 metres (8,630 ft)

- Last ruler – iraca Sugamuxi

- Date of conquest – Early September 1537 (Sogamoso) – Jiménez & Pérez de Quesada

- Important settlements – Suamox, Busbanzá, Firavitoba, Gámeza and Tota

- Archaeological remains – mummies, Sun Temple reconstruction, Lake Tota

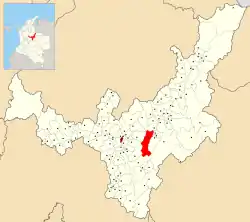

| Municipality | Department | Ruler(s) bold is seat |

Altitude (m) |

Surface area (km2) |

Remarks | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suamox | Boyacá | iraca Nompanim Sugamuxi |

2569 | 208.54 | Sun Temple Muisca mummy found Muisca carbon mines |

|

| Aquitania | Boyacá | iraca | 3030 | 943 | Lake Tota |  |

| Busbanzá | Boyacá | iraca | 2472 | 22.5 | Elector of new iraca |  |

| Cuítiva | Boyacá | iraca | 2750 | 43 | Lake Tota Statue of Bochica |

|

| Firavitoba | Boyacá | iraca | 2500 | 109.9 | Elector of new iraca |  |

| Gámeza | Boyacá | iraca | 2750 | 88 | Herrera site Muisca mummy found Minor Muisca salt mines Muisca carbon mines Petrographs found |

|

| Iza | Boyacá | iraca | 2560 | 34 | Herrera site Lake Tota Petrographs found |

|

| Mongua | Boyacá | iraca | 2975 | 365.5 | Petrographs found |  |

| Monguí | Boyacá | iraca | 2900 | 81 | Petroglyphs Birth places (Tortolitas) |

|

| Pesca | Boyacá | iraca | 2858 | 282 |  | |

| Tasco | Boyacá | iraca | 2530 | 167 | Muisca mummy found |  |

| Toca | Boyacá | iraca | 2810 | 165 |  | |

| Tota | Boyacá | iraca | 2870 | 314 | Lake Tota |  |

| Socotá | Boyacá | iraca Tundama |

2443 | 600.11 | Muisca mummy found |  |

| Tibasosa | Boyacá | Tundama iraca |

2538 | 94.3 |  | |

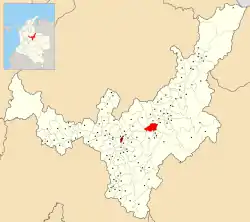

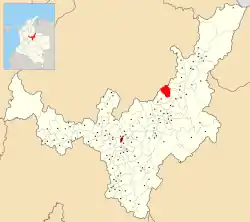

Tundama

- Capital – Tundama

- Area – 2,920 square kilometres (1,130 sq mi)

- Average elevation – 2,470 metres (8,100 ft)

- Last ruler – Tundama

- Date of conquest – Late December 1539 (Duitama) – Baltasar Maldonado

- Important settlements – Tundama, Onzaga, Soatá, Chitagoto (now Paz de Río)

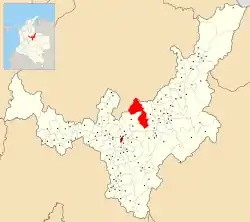

| Municipality | Department | Ruler(s) bold is seat |

Altitude (m) |

Surface area (km2) |

Remarks | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tundama | Boyacá | Tundama | 2590 | 266.93 | Seat of Tundama In ancient lake |

|

| Onzaga | Santander | Tundama | 1960 | 486.76 | Important for wool and cotton production |  |

| Cerinza | Boyacá | Tundama | 2750 | 61.63 | Monument to the Muisca |  |

| Paz de Río | Boyacá | Tundama | 2200 | 116 | Coca market town |  |

| Paipa | Boyacá | Tundama | 2525 | 305.924 | Thermal springs |  |

| Sativanorte | Boyacá | Tundama | 2600 | 184 | Herrera site |  |

| Sativasur | Boyacá | Tundama | 2600 | 81 | Muisca mummy SO10-IX found Herrera site |

|

| Soatá | Boyacá | Tundama | 1950 | 136 | Herrera site Coca market town |

|

| Belén | Boyacá | Tundama | 2650 | 83.6 | Petrographs found |  |

| Corrales | Boyacá | Tundama | 2470 | 60.85 |  | |

| Floresta | Boyacá | Tundama | 2506 | 86 |  | |

| Nobsa | Boyacá | Tundama | 2510 | 55.39 |  | |

| Santa Rosa de Viterbo | Boyacá | Tundama | 2753 | 107 |  | |

| Susacón | Boyacá | Tundama | 2480 | 191 |  | |

| Tibasosa | Boyacá | Tundama iraca |

2538 | 94.3 |  | |

| Socotá | Boyacá | iraca Tundama |

2443 | 600.11 | Muisca mummy found |  |

Independent caciques

- Capital – none

- Area – 3,080 square kilometres (1,190 sq mi)

- Average elevation – 2,140 metres (7,020 ft)

- Important caciques – Guatavita, Ubaté, Chiquinquirá, Ubaque, Tenza, Vélez

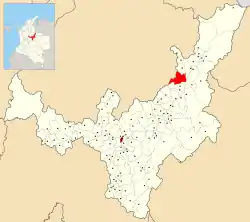

| Municipality bold is major cacique |

Department | Ruler(s) | Altitude (m) |

Surface area (km2) |

Remarks | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vélez | Santander | cacique | 2050 | 271.34 |  | |

| Chipatá | Santander | cacique | 1820 | 94.17 | First town conquered by the Spanish |  |

| Güepsa | Santander | cacique | 1540 | 33.08 | Border with Guane Border with Yarigui |

|

| Charalá | Santander | cacique | 1290 | 411 | Border with Guane |  |

| Arcabuco | Boyacá | cacique | 2739 | 155 | Statue honouring the Muisca warriors |  |

| Betéitiva | Boyacá | cacique | 2575 | 123 |  | |

| Boavita | Boyacá | cacique | 2114 | 159 | Muisca mummy found |  |

| Chiquinquirá | Boyacá | cacique | 2556 | 133 |  | |

| Cómbita | Boyacá | cacique | 2825 | 149 |  | |

| Covarachía | Boyacá | cacique | 2320 | 103 | Herrera site |  |

| Guateque | Boyacá | cacique | 1815 | 36.04 | Religious rituals at Guatoc hill |  |

| Guayatá | Boyacá | cacique | 1767 | 112 | Muisca money (tejuelo) found |  |

| Moniquirá | Boyacá | cacique | 1669 | 220 | Muisca mummy found Muisca copper mines |

|

| Pisba | Boyacá | cacique | 2400 | 469.12 | Muisca mummy found |  |

| Ráquira | Boyacá | cacique | 2150 | 233 | Muisca ceramics production |  |

| Saboyá | Boyacá | cacique | 2600 | 246.9 | Petrographs found |  |

| Tópaga | Boyacá | cacique | 2900 | 37 | Muisca mummy found Muisca carbon mines |

|

| Tutazá | Boyacá | cacique | 1890 | 135 | Muisca ceramics production |  |

| Tenza | Boyacá | cacique | 1600 | 51 | Tenza Valley |  |

| Chivor | Boyacá | cacique | 1800 | 108.36 | Muisca emerald mines |  |

| Úmbita | Boyacá | cacique | 2480 | 148.17 |  | |

| Carmen de Carupa | Cundinamarca | cacique | 2600 | 228 | Tunjo found |  |

| Guatavita | Cundinamarca | cacique | 2680 | 247.3 | Muisca ceramics production Main goldworking town Petrographs found |

|

| Gachetá | Cundinamarca | cacique Guatavita | 1745 | 262.2 |  | |

| Guachetá | Cundinamarca | cacique | 2688 | 177.45 | Minor Muisca salt mines Petrographs found |

|

| Manta | Cundinamarca | cacique | 1924 | 105 |  | |

| Ubaque | Cundinamarca | cacique | 1867 | 104.96 | Last public religious ritual (1563) Lake Ubaque |

|

| Ubalá | Cundinamarca | cacique | 1949 | 505 | Muisca emerald mines |  |

| Chipaque | Cundinamarca | cacique | 2400 | 139.45 | Petrographs found |  |

| Fómeque | Cundinamarca | cacique | 1895 | 555.7 |  | |

| Quetame | Cundinamarca | cacique | 1496 | 138.47 |  | |

| Une | Cundinamarca | cacique | 2376 | 221 |  | |

| Fosca | Cundinamarca | cacique | 2080 | 126.02 | Fortification against Guayupe |  |

Neighbouring indigenous groups

| Yarigui | Guane | Lache | U'wa | ||

| Muzo |  |

.png.webp) | |||

| Panche | Achagua | ||||

| Sutagao | Guayupe | Tegua | |||

| Cariban languages • Chibchan languages • Arawakan languages | |||||

| Yarigui and Lache not shown on map • Tegua shown as Tecua • U'wa shown as Tunebo | |||||

| [22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31] | |||||

- Panche

- Cariban-speaking

- frequent warfare

- beaten in the Battle of Tocarema

- pathways to gold

- conquest by Hernán Venegas Carrillo (1543–44)

- Muzo or The Emerald people

- Cariban-speaking

- trading access to western neighbours

- Furatena

- pathways to gold

- conquest by Luis Lanchero (1539–1559)

- Guane

- Chibcha-speaking

- producers of cotton for mantle making

- producers of fruits

- access to La Tora (Barrancabermeja); trading sea shells at Magdalena River

- conquest by Martín Galeano (1539–1551)

Sacred sites

The sacred sites of the Muisca Confederation were based in the Muisca religion and mythology. The Muisca were a highly religious people with their own beliefs on the origin of the Earth and life and human sacrifices were no exception to please the gods for good harvests and prosperity.

Lake Guatavita, Guatavita, was the location where the new zipa would be inaugurated. It became known with the Spanish conquerors as the site of El Dorado where the new zipa was covered in gold dust and installed as the new ruler of the southern Muisca.[32]

In the legends of the Muisca, mankind originated in Lake Iguaque, Monquirá, when the goddess Bachué came out from the lake with a boy in her arms. When the boy grew, they populated the Earth. They are considered the ancestors of the human race. Finally, they disappeared unto the lake in the shape of snakes.[33]

According to Muisca myths, the Tequendama Falls, outside Soacha, was the site where the first zipa Meicuchuca lost his beautiful lover who turned in a snake and disappeared in the waters of the Bogotá River.[34][35]

El Infiernito, close to the present town of Villa de Leyva was a sacred site where the Muisca erected structures based on astronomical parameters.[36][37][38]

Other sacred sites

- Sun Temple, Sogamoso

- Hunzahúa Well, Tunja

- Goranchacha Temple, Tunja

- Cojines del Zaque, Tunja

- Moon Temple, Chía

Lake Guatavita; site of El Dorado

Lake Guatavita; site of El Dorado Lake Iguaque

Lake Iguaque Tequendama Falls

Tequendama Falls El Infiernito; astronomical site

El Infiernito; astronomical site.JPG.webp) Cojines del Zaque

Cojines del Zaque

Spanish conquests

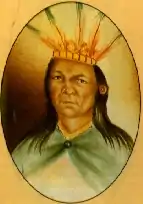

(† 1537)

(† 1540)

Conquest and early colonial period

The conquest of the Muisca was the heaviest of all four Spanish expeditions to the great American civilisations.[39] More than 80 percent of the soldiers and horses that started the journey of a year to the northern Muisca Confederation didn't make it.[40][41][42] Various settlements were founded by the Spanish between 1537 and 1539.[43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52]

A delegation of more than 900 men left the tropical city of Santa Marta and went on a harsh expedition through the heartlands of Colombia in search of El Dorado and the civilisation that produced all this precious gold. The leader of the first and main expedition under Spanish flag was Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, with his brother Hernán second in command.[42] Several other soldiers were participating in the journey, who would later become encomenderos and taking part in the conquest of other parts of Colombia. Other contemporaneous expeditions into the unknown interior of the Andes, all searching for the mythical land of gold, were starting from later Venezuela, led by Bavarian and other German conquistadors and from the south, starting in the previously founded Kingdom of Quito in later Ecuador.

The first phase of the conquest was ended by the victory of the few conquistadors left over Tisquesusa, the last zipa of Bacatá, who fell and died "bathing in his own blood"after the battle at Funza, on the Bogotá savanna, April 20, 1537. The arrival of the Spanish conquerors was revealed to Tisquesusa by the mohan Popón, from the village of Ubaque. He told the Muisca ruler that foreigners were coming and Tisquesusa would die "bathing in his own blood".[53] When Tisquesusa was informed of the advancing invasion of the Spanish soldiers, he sent a spy to Suesca to find out more about their army strength, weapons and with how many warriors they could be beaten. The zipa left the capital Bacatá and took shelter in Nemocón which directed the Spanish troops to there, during this march attacked by more than 600 Muisca warriors.[54]

When Tisquesusa retreated in his fort in Cajicá he allegedly told his men he would not be able to combat against the strong Spanish army in possession of weapons that produced "thunder and lightning". He chose to return to Bacatá and ordered the capital to be evacuated, resulting in an abandoned site when the Spanish arrived. In search for the Muisca ruler the conquistadores went north to find Tisquesusa in the surroundings of Facatativá where they attacked him at night.

Tisquesusa was thrusted by the sword of one of De Quesada's soldiers but without knowing he was the zipa he let him go, after taking the expensive mantle of the ruler. Tisquesusa fled hurt into the mountains and died of his wounds there. His body was only discovered a year later because of the black vultures circling over it.

When Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada found out the caciques were conspiring against him, he sent out several expeditions of soldiers. His captain Juan de Céspedes went south to found Pasca on July 15, 1537.[55] Hernán was sent north and Gonzalo himself went northeast, to search for the mythical Land of Gold El Dorado. There he didn't find golden cities, but emeralds, the Muisca were extracting in Chivor and Somondoco. First foundation was Engativá, presently a locality of Bogotá, on May 22, 1537.[48] Passing through Suba, Chía, Cajicá, Tocancipá, Gachancipá, Guatavita and Sesquilé, he arrived in Chocontá, founding the modern town on June 9.[49] The journey went eastward into the Tenza Valley through Machetá, Tibiritá, Guateque, Sutatenza and Tenza, founded on San Juan; June 24.[50] On the same day, Hernán founded Sutatausa.[51] Gonzalo continued northwest through La Capilla and Úmbita. He arrived in Turmequé that he founded on July 20.[52]

In August 1537 Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada entered the territories of the zaque, who ruled from Hunza. When the Spanish conquerors entered the outskirts of Hunza and found a hill with poles were bodies were dangling, they named it Cerro de la Horca ("Gallow Hill").[56] At the time of the conquest Quemuenchatocha was the zaque and he ordered his men to not submit to the European invaders or show them the way to his bohío. He sent messengers to the Spanish conquistadors with valuable peace offers. While this was happening, Quemuenchatocha had hidden his treasures from the Spanish. Hunza was located in a valley not as green as the Bogotá savanna. The advantage of the Spanish weaponry and the use of the horses quickly beat the Muisca warriors.[42]

When Gonzalo arrived at the main bohío of Quemuenchatocha, he found the Muisca ruler sitting in his throne and surrounded by his closest companions. All men were dressed in expensive mantles and adorned with golden crowns. On August 20, 1537, the Spanish beat the zaque and the big and strong Muisca ruler was taken captive to Suesca. There he was tortured and the Spanish soldiers hoped he would reveal where he hid his precious properties. The absence of Quemuenchatocha paved the route for his nephew Aquiminzaque to succeed him as ruler of the northern Muisca, a practice common in Muisca traditions. When Quemuenchatocha was finally released from captivity in Suesca, he fled to Ramiriquí, where he died shortly after. The Spanish soldiers found gold, emeralds, silver, mantles and other valuables in Tunja. They were not able to take all the precious pieces and many were secretly taken away by the Muisca, using folded deer skins. They hid the valuables in nearby hills.[42]

|

Feb 1537 | First contact @ Chipatá | ||

| Mar–Apr 1537 | Expedition into Muisca Confederation | |||

| 20 Apr 1537 | Conquest of Funza upon zipa Tisquesusa | |||

| May–Aug 1537 | Expedition & conquest in Tenza Valley | |||

| 20 Aug 1537 | Conquest Hunza, zaque Quemuenchatocha | |||

| Early Sep 1537 | Conquest Sugamuxi, iraca Sugamuxi | |||

|

Oct 1537 – Feb 1538 | Other foundations on Altiplano & valleys | ||

| 6 Aug 1538 | Foundation Santafé de Bogotá, by Gonzalo | |||

| 20 Aug 1538 | B. of Tocarema; Spanish & zipa beat Panche | |||

| 6 Aug 1539 | Foundation Tunja, by Gonzalo Suárez | |||

| 15 Dec 1539 | Conquest Tundama, by Baltasar Maldonado | |||

| Early 1540 | Decapitation last zaque Aquiminzaque, Hernán | |||

- I – Soldiers of the main expedition – Santa Marta-Funza and on – February – April 20, 1537

| Name leader in bold |

Nationality | Years active |

Encountered bold is conquered |

Year of death |

Image | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada |

Granadian | 1536–39 1569–72 |

zipa zaque |

1579 |  |

[39][40][42] |

| Juan Maldonado | Castilian | 1536–39 1569–72 |

Muisca | [40][note 2] | ||

| Gonzalo Macías | Castilian | 1536–39 1569–71 |

Muisca | 1571~ | [40][57] | |

| Hernán Pérez de Quesada |

Granadian | 1536–39 1540–42 |

Muisca | 1544 | [40][42] | |

| Gonzalo Suárez Rendón | Castilian | 1536–39 | zipa, zaque | 1590 | [40][42][58] | |

| Martín Galeano | Castilian | 1536–39 1540–45 |

Muisca | 1554~ | [40][42][59] | |

| Lázaro Fonte | Castilian | 1536–39 1540–42 |

Muisca | 1542 | [40][42] | |

| Juan de Céspedes | Castilian | 1525–43 | Muisca | 1573 or 1576 | [40][42][60][61] | |

| Juan de San Martín | Castilian | 1536–39 1540–45 |

Muisca | [40][42] | ||

| Antonio de Lebrija | Castilian | 1536–39 | Muisca | 1540 | [40] | |

| Ortún Velázquez de Velasco | Castilian | 1536–39 | Muisca | 1584 | [40][62] | |

| Bartolomé Camacho Zambrano | Castilian | 1536–39 | Muisca | [40] | ||

| Antonio Díaz de Cardoso | Castilian | 1536–39 | Muisca | [40] | ||

| Pedro Fernández de Valenzuela | Castilian | 1536–39 | Muisca | [40] | ||

| 640+ conquistadors ~80% |

mostly Castilian | April 1536 - April 1537 |

Diseases, jaguars, crocodiles, climate, various indigenous warfare |

1536 1537 |

|

[40][42] |

- II & III – Soldiers of the expeditions De Belalcázar & Federmann (1535–1539)

| Name leader in bold |

Nationality | Years active |

Encountered bold is conquered |

Year of death |

Image | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sebastián de Belalcázar | Castilian | 1514–39 | Muisca | 1551 | _-_AHG.jpg.webp) |

[39][42] |

| Baltasar Maldonado | Castilian | 1543–52 | Muisca | 1552 | [63][64][65][66] | |

| Nikolaus Federmann | Bavarian | 1535–39 | Muisca | 1542 | [39][42] | |

| Miguel Holguín y Figueroa | Castilian | 1535–39 | Muisca | 1576> | [67] | |

- I – 1 – Main expedition – inland and up from Chipatá to Funza – March – April 1537

| Settlement bold is founded |

Department | Date | Year | Altitude (m) urban centre |

Notes | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chipatá | Santander | 8 March | 1537 | 1820 | [42][43] |  |

| Barbosa | Santander | March | 1537 | 1610 |  | |

| Moniquirá | Boyacá | March | 1537 | 1669 | [68][note 3] |  |

| Santa Sofía | Boyacá | March | 1537 | 2387 |  | |

| Sutamarchán | Boyacá | March | 1537 | 1800 |  | |

| Ráquira | Boyacá | March | 1537 | 2150 | [69] |  |

| Simijaca | Cundinamarca | March | 1537 | 2559 |  | |

| Susa | Cundinamarca | March | 1537 | 2655 |  | |

| Fúquene | Cundinamarca | March | 1537 | 2750 |  | |

| Guachetá | Cundinamarca | 12 March | 1537 | 2688 | [44] |  |

| Lenguazaque | Cundinamarca | 13 March | 1537 | 2589 | [45] |  |

| Cucunubá | Cundinamarca | 13–14 March | 1537 | 2590 |  | |

| Suesca | Cundinamarca | 14 March | 1537 | 2584 | [46] |  |

| Nemocón | Cundinamarca | March | 1537 | 2585 | [42] |  |

| Zipaquirá | Cundinamarca | March | 1537 | 2650 |  | |

| Cajicá | Cundinamarca | 23 March | 1537 | 2558 | [42][70] |  |

| Chía | Cundinamarca | 24 March | 1537 | 2564 | [42][71] |  |

| Cota | Cundinamarca | March–April | 1537 | 2566 |  | |

| Funza | Cundinamarca | 20 April | 1537 | 2548 | [42][47] |  |

- I – 2 – Gonzalo – Tenza Valley – Conquest of Hunza & Sugamuxi – May – August 20 & September, 1537

| Settlement bold is founded |

Department | Date | Year | Note(s) | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engativá | Cundinamarca | 22 May | 1537 | [48] |  |

| Suba | Cundinamarca | May | 1537 |  | |

| Chía | Cundinamarca | May | 1537 |  | |

| Cajicá | Cundinamarca | May | 1537 |  | |

| Tocancipá | Cundinamarca | May–June | 1537 |  | |

| Gachancipá | Cundinamarca | May–June | 1537 |  | |

| Guatavita | Cundinamarca | May–June | 1537 |  | |

| Sesquilé Lake Guatavita El Dorado |

Cundinamarca | May–June | 1537 |  | |

| Chocontá | Cundinamarca | 9 June | 1537 | [49] |  |

| Machetá | Cundinamarca | June | 1537 |  | |

| Tibiritá | Cundinamarca | June | 1537 |  | |

| Guateque | Boyacá | June | 1537 |  | |

| Sutatenza | Boyacá | June | 1537 |  | |

| Tenza | Boyacá | 24 June | 1537 | [50] |  |

| La Capilla | Boyacá | June–July | 1537 |  | |

| Chivor | Boyacá | July | 1537 | [72] |  |

| Úmbita | Boyacá | July | 1537 |  | |

| Turmequé | Boyacá | 20 July | 1537 | [52] |  |

| Boyacá | Boyacá | 8 August | 1537 | [73] |  |

| Ciénega | Boyacá | August | 1537 |  | |

| Soracá | Boyacá | 20 August ~15:00 | 1537 | [74] |  |

| Hunza | Boyacá | 20 August | 1537 | [74] |  |

- 3 – Hernán – Foundation of Sutatausa – June 24, 1537

| Name | Department | Date | Year | Note(s) | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sutatausa | Cundinamarca | 24 June | 1537 | [51] |  |

- 4 – Juan de Céspedes – Southern savanna – 1537

| Name | Department | Date | Year | Note(s) | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pasca | Cundinamarca | 15 July | 1537 | [55] |  |

| San Antonio del Tequendama | Cundinamarca | 1539 | [75] |  | |

- 5 – Juan de San Martín – 1537–1550

| Name | Department | Date | Year | Note(s) | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Colegio | Cundinamarca | 1537 | [76] |  | |

| Cuítiva | Boyacá | 19 January | 1550 | [77] |  |

- 6 – Gonzalo et al. – Foundations of Bogotá and savanna

| Name | Department | Date | Year | Note(s) | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bojacá | Cundinamarca | 16 October | 1537 | [78] |  |

| Somondoco | Boyacá | 1 November | 1537 | [79] |  |

| Une | Cundinamarca | 23 February | 1538 | [80] |  |

- 7 – Gonzalo Suárez Rendón – Foundation of Tunja – August 6, 1539

| Name | Department | Date | Year | Note(s) | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tunja | Boyacá | 6 August | 1539 |  | |

- 8 – Baltasar Maldonado – Conquest of Tundama – December 1539

| Name | Department | Date | Year | Note(s) | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duitama | Boyacá | 15 December | 1539 | [81] |  |

- 9 – Hernán & Lázaro Fonte a.o. – 1540

| Name | Department | Date | Year | Note(s) | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motavita | Boyacá | 1540 | [82] |  | |

| Nevado del Sumapaz | Cundinamarca | 1540 |  | ||

Early colonial period

| Year(s) | Epidemic |

|---|---|

| 1537 | Tunja Province: ~250,000 est. inh. |

| 1558< | no data |

| 1558-60 | smallpox, measles |

| 1568-69 | influenza |

| 1587-90 | influenza (or typhus) |

| 1607 | smallpox |

| 1617-18 | measles (after food shortages) |

| 1621 | smallpox |

| 1633 | typhus |

| 1636 | Tunja Province: ~50,000 est. inh. -80% |

Not only the Spanish settlers had lost large percentages of their men due to warfare and diseases. The assessed corregimientos of the Province of Tunja between 1537 and 1636 shows a decline of the total Muisca population between 65 and 85%.[83] Epidemics were the main cause of the rapid reduction in population. Various have been reported and many undescribed in the first twenty years of contact.[84]

After the foundation of Bogotá and the installation of the new dependency of the Spanish Crown, several strategies were important to the Spanish conquerors. The rich mineral resources of the Altiplano had to be extracted, the agriculture was quickly reformed, a system of encomiendas was installed and a main concern of the Spanish was the evangelisation of the Muisca. On October 9, 1549, Carlos V sent a royal letter to the New Kingdom directed at the priests about the necessity of population reduction of the Muisca.[85] The indigenous people were working in the encomiendas which limited their religious conversion.[85] To speed up the process of submittance to the Spanish reign, the mobility of the indigenous people was prohibited and the people gathered in resguardos.[86] The formerly celebrated festivities in their religion disappeared. Specific times for the catechesis were controlled by laws, as executed in royal dictates in 1537, 1538 and 1551.[87] The first bishop of Santafé, Juan de los Barrios, ordered to destroy the temples of the Muisca and replace them with catholic churches.[88] The last public religious ceremony of the Muisca religion was held in Ubaque on December 27, 1563.[89] The second bishop of Santafé, Luis Zapata de Cárdenas, intensified the aggressive policies against the Muisca religion and the burnings of their sacred sites. This formed the final nail in the coffin of the former polytheistic society.[88]

The transition to a mixed agriculture with Old World crops was remarkably fast, mainly to do with the fertility of the lands of the Altiplano permitting European crops to grow there, while in the more tropical areas the soil was not so much suited for the foreign crops. In 1555, the Muisca of Toca were growing European crops as wheat and barley and sugarcane was grown in other areas.[90] The previously self-sustaining economy was quickly transformed into one based on intensive agriculture and mining that produced changes in the landscape and culture of the Muisca.[91]

See also

Notes

- While some sources state 47,000 km² as area,[1] that would be Cundinamarca and Boyacá combined and other indigenous groups were living in those areas

- Not the same as Juan Maldonado, who was only 11 in 1536

- Note: date of foundation says March 16, 1537, which cannot be correct, as the troops were already in Cundinamarca by that date

References

- (in Spanish) Muisca Confederation area almost 47,000 km2, page 12

- (in Spanish) Muisca culture – Historia Universal – accessed 21-04-2016

- Gamboa Mendoza, 2016

- (in Spanish) Nivel Paleoindio. Abrigos rocosos del Tequendama Archived 2016-04-29 at Archive.today

- Gómez Mejía, 2012, p.153

- Ocampo López, 2007, p.27

- Ocampo López, 2007, p.26

- (in Spanish) Herrera Period – Universidad Nacional de Colombia

- (in Spanish) Chronology of pre-Columbian periods: Herrera and Muisca

- Kruschek, 2003

- Langebaek, 1995, Ch.4, p.70

- Izquierdo Peña, 2009

- (in Spanish) Muysccubun: chie

- Casimilas Rojas, 2005, p.250

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1947, p.30

- Quesada & Rojas, 1999, p.93

- (in Spanish) Muysccubun: ata

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1947, p.38

- (in Spanish) Muysccubun: muysca

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1947, p.25

- (in Spanish) Reconstruction of the Guane people – El Espectador

- (in Spanish) Las Tribus Indígenas en Colombia

- Chibcha-speaking U'wa

- Achagua in Encyclopædia Britannica

- (in Spanish) Official website Miraflores

- (in Spanish) Description Guayupe

- (in Spanish) Indios Sutagaos

- The lost Panches

- (in Spanish) El vocabulario Muzo-Colima de la relación de Juan Suárez de Cepeda (1582)

- (in Spanish) Apuntes para el análisis de la situación de la lengua Carare

- (in Spanish) Legend of El Dorado on the shores of Lake Guatavita Archived 2016-04-04 at the Wayback Machine – Casa Cultural Colombiana – accessed 21-04-2016

- (in Spanish) Birth of mankind from Lake Iguaque – Cultura, Recreación y Deporte – accessed 21-04-2016

- (in Spanish) Legend of the lover of Meicuchuca turning into a snake in the Tequendama Fallas – Pueblos Originarios – accessed 21-04-2016

- Ocampo López, 2013, Ch.18, p.99

- (in Spanish) El Infiernito; astronomical site – Pueblos Originarios

- Langebaek, 2005b, p.282

- Izquierdo, 2014

- (in Spanish) Personajes de la Conquista a América – Banco de la República

- (in Spanish) List of conquistadors led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada – Banco de la República

- (in Spanish) Biography Hernán Pérez de Quesada – Banco de la República

- (in Spanish) Conquista rápida y saqueo cuantioso de Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada

- (in Spanish) Official website Chipatá Archived 2015-06-07 at Archive.today

- (in Spanish) Official website Guachetá Archived 2017-07-09 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Official website Lenguazaque

- (in Spanish) Official website Suesca

- (in Spanish) Official website Funza Archived 2015-12-21 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Engativá celebra hoy sus 458 años – El Tiempo

- (in Spanish) Official website Chocontá

- (in Spanish) Official website Tenza Archived 2015-06-02 at Archive.today

- (in Spanish) Official website Sutatausa Archived 2016-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Official website Turmequé Archived 2016-01-12 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Tisquesusa would die bathing in his own blood – Pueblos Originarios

- (in Spanish) Zipa Tisquesusa – Banco de la República

- (in Spanish) Official website Pasca Archived 2015-05-22 at Archive.today

- (in Spanish) Biography Quemuenchatocha – Pueblos Originarios

- Rodríguez Freyle, 1979 (1638), p.173

- Rodríguez Freyle, 1979 (1638), p.84

- Rodríguez Freyle, 1979 (1638), p.144

- (in Spanish) Biography Juan de Céspedes – Banco de la República

- Rodríguez Freyle, 1979 (1638), p.69

- Rodríguez Freyle, 1979 (1638), p.xii

- (in Spanish) Baltasar Maldonado – Soledad Acosta Samper – Banco de la República

- Rodríguez Freyle, 1979 (1638), p.88

- Rodríguez Freyle, 1979 (1638), p.93

- Rodríguez Freyle, 1979 (1638), p.94

- Rodríguez Freyle, 1979 (1638), p.153

- (in Spanish) Official website Moniquirá

- (in Spanish) Official website Ráquira

- (in Spanish) History Cajicá

- (in Spanish) De Quesada celebrated the Holy Week in Chia

- (in Spanish) History Chivor Archived 2016-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Official website Boyacá

- (in Spanish) Official website Soracá

- (in Spanish) Official website San Antonio del Tequendama

- (in Spanish) Official website El Colegio

- (in Spanish) Official website Cuítiva

- (in Spanish) Official website Bojacá Archived 2017-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Official website Somondoco Archived 2015-06-02 at Archive.today

- (in Spanish) Official website Une

- (in Spanish) Biography Cacique Tundama – Pueblos Originarios

- (in Spanish) Official website Motavita Archived 2014-03-10 at Archive.today

- Francis, 2002, p.59

- Francis, 2002, p.42

- Suárez, 2015, p.128

- Segura Calderón, 2014, p.38

- Suárez, 2015, p.125

- Suárez, 2015, p.129

- Londoño, 2001, p.4

- Francis, 1993, p.60

- Martínez & Manrique, 2014, p.102

Bibliography and further reading

- Acosta, Joaquín. 1848. Compendio histórico del descubrimiento y colonización de la Nueva Granada en el siglo décimo sexto, 1–460. Beau Press. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Francis, John Michael. 2002. Población, enfermedad y cambio demográfico, 1537–1636. Demografía histórica de Tunja: Una mirada crítica. Fronteras de la Historia 7. 13–76.

- Francis, John Michael. 1993. "Muchas hipas, no minas" The Muiscas, a merchant society: Spanish misconceptions and demographic change (M.A.), 1–118. University of Alberta.

- Gamboa Mendoza, Jorge. 2016. Los muiscas, grupos indígenas del Nuevo Reino de Granada. Una nueva propuesta sobre su organizacíon socio-política y su evolucíon en el siglo XVI – The Muisca, indigenous groups of the New Kingdom of Granada. A new proposal on their social-political organization and their evolution in the 16th century. Museo del Oro. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Gamboa Mendoza, Jorge. 2003. El papel de la minería en la formación de la economía y la sociedad colonial del Nuevo Reino de Granada, siglos XVI-XVIII – The role of mining in the formation of the economy and colonial society of the New Kingdom of Granada, 16th–18th centuries. Takwá _. 1–24. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Groot de Mahecha, Ana María. 2014 (2008). Sal y poder en el altiplano de Bogotá, 1537–1640, 1–174. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- Groot de Mahecha, Ana María. 1992. Checua: Una secuencia cultural entre 8500 y 3000 años antes del presente - Checua: a cultural sequence between 8500 and 3000 years before present, 1–95. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Henderson, Hope, and Nicholas Ostler. 2005. Muisca settlement organization and chiefly authority at Suta, Valle de Leyva, Colombia: A critical appraisal of native concepts of house for studies of complex societies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 24. 148–178.

- Izquierdo Peña, Manuel Arturo. 2014. Calendario Muisca – Muisca calendar. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Izquierdo Peña, Manuel Arturo. 2009. The Muisca Calendar: An approximation to the timekeeping system of the ancient native people of the northeastern Andes of Colombia (PhD), 1–170. Université de Montréal. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Kruschek, Michael H.. 2003. The evolution of the Bogotá chiefdom: A household view (PhD), 1–271. University of Pittsburgh. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 2005a. La élite no siempre piensa lo mismo – The elite does not always think the same, 180–199. Universidad La Javeriana.

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 2005b. Fiestas y caciques muiscas en el Infiernito, Colombia: un análisis de la relación entre festejos y organización política - Festivities and Muisca caciques in El Infiernito, Colombia: an analysis of the relation between celebrations and political organisation. Boletín de Arqueología 9. 281–295.

- Martínez Martín, A. F., and E. J. Manrique Corredor. 2014. Alimentación prehispánica y transformaciones tras la conquista europea del altiplano cundiboyacense, Colombia. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte 41. 96–111. Accessed 2018-07-28.

- Ocampo López, Javier. 2013. Mitos y leyendas indígenas de Colombia – Indigenous myths and legends of Colombia. Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A..

- Ocampo López, Javier. 2007. Grandes culturas indígenas de América - Great indigenous cultures of the Americas, 1–238. Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A..

- Paepe, Paul de, and Marianne Cardale de Schrimpff. 1990. Resultados de un estodio petrológico de cerámicas del Periodo Herrera provenientes de la Sabana de Bogotá y sus implicaciones arqueológicas – Results of a petrological study of ceramics form the Herrera Period coming from the Bogotá savanna and its archaeological implications. Boletín Museo del Oro _. 99–119. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Cardale de Schrimpff, Marianne. 1985. En busca de los primeros agricultores del Altiplano Cundiboyacense – Searching for the first farmers of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, 99–125. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Trimborn, Hermann. 2005. La organización del poder público en las culturas soberanas de los chibchas – The public power organisation in the common cultures of the Chibchas, 298–314. Universidad La Javeriana.

- Zerda, Liborio. 1947 (1883). El Dorado. Accessed 2016-07-08.

Spanish chroniclers

- N, N. 1979 (1889) (1539/1548-1559?). Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada, 81–97. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-11-24.

- Jiménez de Quesada, Gonzalo. 1576. Memoria de los descubridores, que entraron conmigo a descubrir y conquistar el Reino de Granada. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- De Castellanos, Juan. 1857 (1589). Elegías de varones ilustres de Indias, 1–567. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- De Lugo, Bernardo. 1619. Gramática en la lengua general del Nuevo Reyno, llamada mosca – Grammar in the general language of the New Kingdom, called Mosca (Muisca), 1–162. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Simón, Pedro. 1892 (1626). Noticias historiales de las conquistas de Tierra Firme en las Indias occidentales (1882–92) vol.1–5. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Rodríguez Freyle, Juan, and Darío Achury Valenzuela. 1979 (1859) (1638). El Carnero – Conquista i descubrimiento del nuevo reino de Granada de las Indias Occidentales del mar oceano, i fundacion de la ciudad de Santa Fe de Bogota, 1–598. Fundacion Biblioteca Ayacuch. Accessed 2016-11-21.

- Fernández de Piedrahita, Lucas. 1688. Historia general de las conquistas del Nuevo Reino de Granada. Accessed 2016-07-08.