Chibcha language

Chibcha is an extinct language of Colombia, spoken by the Muisca, one of the many advanced indigenous civilizations of the Americas. The Muisca inhabited the central highlands (Altiplano Cundiboyacense) of what today is the country of Colombia.

| Chibcha | |

|---|---|

| Muisca or Muysca | |

| Muysccubun | |

| Pronunciation | mʷɨskkuβun |

| Native to | Colombia |

| Region | Altiplano Cundiboyacense |

| Ethnicity | Muisca |

| Extinct | ca. 1800[1] |

Chibchan

| |

| Dialects | Duit |

| only numerals | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | chb |

| ISO 639-3 | chb |

| Glottolog | chib1270 |

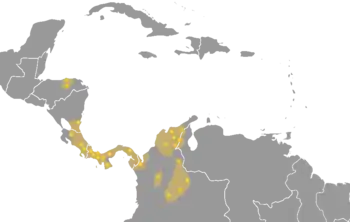

Chibcha was spoken in the southernmost area; Central-Colombia | |

The name of the language Muysc Cubun in its own language means "language of the people" or "language of the men", from muysca ("people" or "men") and cubun ("language" or "word").[2]

Important scholars who have contributed to the knowledge of the Chibcha language were Juan de Castellanos, Bernardo de Lugo, José Domingo Duquesne and Ezequiel Uricoechea.

History

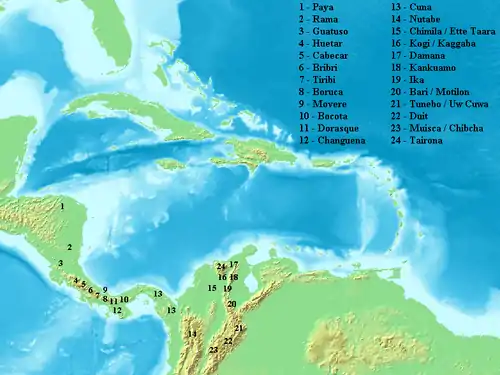

In prehistorical times, in the Andean civilizations called preceramic, the population of northwestern South America happened through the Darien Gap between the isthmus of Panama and Colombia. Other Chibchan languages are spoken in southern Central America and the Muisca and related indigenous groups took their language with them into the heart of Colombia where they settled in their Muisca Confederation.

Spanish colonization

As early as 1580 the authorities in Charcas, Quito, and Santa Fe de Bogotá mandated the establishment of schools in native languages and required that priests study these languages before ordination. In 1606 the entire clergy was ordered to provide religious instruction in Chibcha. The Chibcha language declined in the 18th century.[3]

In 1770, King Charles III of Spain officially banned use of the language in the region [3] as part of a de-indigenization project. The ban remained in law until Colombia passed its constitution of 1991.

Modern history

Modern Muisca scholars have investigated Muysccubun and concluded that the variety of languages was much larger than previously thought. The quick colonization of the Spanish and the improvised use of traveling translators has reduced the differences between the versions of Chibcha over time.[4]

Since 2009 an online Spanish-Muysccubun dictionary containing more than 2000 words is online. The project was partly financed by the University of Bergen, Norway.[5]

Greetings in Chibcha[6]

- chibú - hello (to 1 person)

- (chibú) yswa - hello to more people

- chowá? - Are you good? [How are you?]

- chowé - I am / we are good

- haspkwa sihipkwá - goodbye!

Alphabet and rough pronunciation

| Phoneme | Letter |

|---|---|

| /i/ | i |

| /ɨ/ | y |

| /u/ | u |

| /e/ | e |

| /o/ | o |

| /a/ | a |

| /p/ | p |

| /t/ | t |

| /k/ | k |

| /b~β/ | b |

| /g~ɣ/ | g |

| /ɸ/ | f |

| /s/ | s |

| /ʂ/ | ch |

| /h/ | h |

| /tʂ/ | zh |

| /m/ | m |

| /n/ | n |

| /w/ | w |

| /j/ | ï |

The muysccubun alphabet consists of around 20 letters. The Muisca didn't have an "L" in their language. The letters are pronounced more or less as follows:[7][8][9]

a - as in Spanish "casa"; ka - "enclosure" or "fence"

e - as in "action"; izhe - "street"

i - open "i" as in "'inca" - sié - "water" or "river"

o - short "o" as in "box" - to - "dog"

u - "ou" as in "you" - uba - "face"

y - between "i" and "e"; "a" in action - ty - "singing"

b - as in "bed", or as in Spanish "haba"; - bohozhá - "with"

- between the vowels "y" it is pronounced [βw] - kyby - "to sleep"

ch - "sh" as in "shine", but with the tongue pushed backwards - chuta - "son" or "daughter"

f - between a "b" and "w" using both lips without producing sound, a short whistle - foï - "mantle"

- before a "y" it's pronounced [ɸw] - fyzha - "everything"

g - "gh" as in "good", or as in Spanish "abogado"; - gata - "fire"

h - as in "hello" - huïá - "inwards"

ï - "i-e" as in Beelzebub - ïe - "road" or "prayer"

k - "c" as in "cold" - kony - "wheel"

m - "m" as in "man" - mika - "three"

- before "y" it's pronounced [mw], as in "Muisca" - myska - "person" or "people"

- in first position before a consonant it's pronounced [im] - mpkwaká - "thanks to"

n - "n" as in "nice" - nyky - "brother" or "sister"

- in first position followed by a consonant it's pronounced [in] - ngá - "and"

p - "p" as in "people" - paba - "father"

- before "y" it's pronounced [pw] as in Spanish "puente" - pyky - "heart"

s - "s" as in "sorry" - sahawá - "husband"

- before "i" changes a little to "sh"; [ʃ] - sié - "water" or "river"

t - "t" as in "text" - yta - "hand"

w - "w" as in "wow!" - we - "house"

zh - as in "chorizo", but with the tongue to the back - zhysky - "head"

The accentuation of the words is like in Spanish on the second-last syllable except when an accent is shown: Bacata is Ba-CA-ta and Bacatá is Ba-ca-TA.

In case of repetition of the same vowel, the word can be shortened: fuhuchá ~ fuchá - "woman".[8]

In Chibcha, words are made of combinations where sometimes vowels are in front of the word. When this happens in front of another vowel, the vowel changes as follows:[10]

a-uba becomes oba - "his (or her, its) face"

a-ita becomes eta - "his base"

a-yta becomes ata - "his hand" (note: ata also means "one")

Sometimes this combination is not performed and the words are written with the prefix plus the new vowel: a-ita would become eta but can be written as aeta, a-uba as aoba and a-yta as ayta

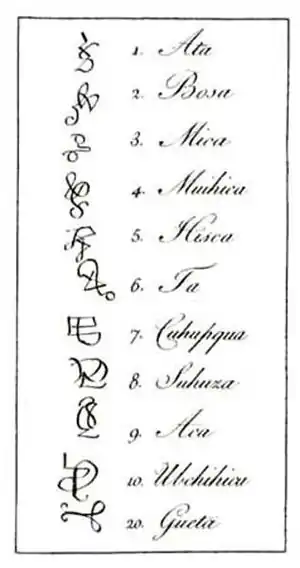

Numbers

Counting 1 to 10 in Chibcha is transl. chb – transl. ata, bozha, mika, myhyká, hyzhká, ta, kuhupkwá, suhuzhá, aka, hubchihiká.[10] The Muisca only had numbers one to ten and the 'perfect' number 20; gueta, used extensively in their complex lunisolar Muisca calendar. For numbers higher than 10 they used additions; hubchikiká asaqui ata ("ten plus one") for eleven. Higher numbers were multiplications of twenty; gue-hisca would be "twenty times five"; 100.

Structure and grammar

Subject

The subjects in Chibcha do not have genders nor plurals. to thus can mean "male dog", "male dogs", "female dog" or "female dogs". To solve this, the Muisca used the numbers and the word for "man"; cha and "woman"; fuhuchá to specify gender and plural:[11]

- to cha ata - "one male dog" (literally: "dog" "male" "one")

- to cha mika - "three male dogs" ("dog male three")

- to fuhuchá myhyká - "four female dogs"

Personal pronoun

| Muysccubun[2] | Phonetic | English |

|---|---|---|

| hycha | /hɨʂa/ | I |

| mue | /mue/ | you (informal and formal) |

| as(y) | /asɨ/ or /as/ | he / she / it / they |

| chie | /ʂie/ | we |

| mie | /mie/ | you (plural) |

Possessive pronoun

The possessive pronoun is placed before the word it refers to.

| Muysccubun[11][12] | English |

|---|---|

| zh(y)- / i- | my |

| (u)m- | your |

| a- | his / her / its / their |

| chi- | our |

| mi- | your (plural) |

- i- is only used in combination with ch, n, s, t or zh; i-to = ito ("my dog")

- zh- becomes zhy- when followed by a consonant (except ï); zh-paba = zhypaba ("my father")

- in case of a ï, the letter is lost: zh-ïohozhá = zhohozhá ("my buttocks")

- m- becomes um- when followed by a consonant; m-ïoky = umïoky ("your book")

- zhy- and um- are shortened when the word starts with w; zhy-waïá & um-waïá = zhwaïá & mwaïá ("mi mother" & "your mother")

- when the word starts with h, zhy- and um- are shortened and the vowel following j repeated; zhy-hué & um-hué = zhuhué & muhué ("my sir" & "your sir")

Verbs

The Muisca used two types of verbs, ending on -skua and -suka; bkyskua ("to do") and guitysuka ("to whip") which have different forms in their grammatical conjugations.[2] bkyskua is shown below, for verbs ending on -suka, see here.

Conjugations

| Muysccubun | English |

|---|---|

| kyka | to do |

| Muysccubun | English |

|---|---|

| ze bkyskua | I do or did |

| um bkyskua | you do or did |

| a bkyskua | he / she / it does or did |

| chi bkyskua | we do/did |

| mi bkyskua | you do/did |

| a bkyskua | they do/did |

- Perfect and pluperfect

| Muysccubun | English |

|---|---|

| ze bky | I did or have done |

| um bky | you did or " " |

| a bky | he / she / it did or has done |

| chi bky | we did or have done |

| mi bky | you did or " " |

| a bky | they did or " " |

| Muysccubun | English |

|---|---|

| ze bkynga | I will do |

| um bkynga | you " " |

| a bkynga | he / she / it " " |

| chi bkynga | we " " |

| mi bkynga | you " " |

| a bkynga | they " " |

Imperatives

| Muysccubun | English |

|---|---|

| kyû | do (singular) |

| kyuua | do (plural) |

| Muysccubun | English |

|---|---|

| cha kyia | may I do |

| ma kyia | may you do |

| kyia | may he / she / it do |

| chi kyia | may we do |

| mi kyia | may you do |

| kyia | may they do |

Selection of words

This list is a selection from the online dictionary and is sortable. Note the different potatoes and types of maize and their meaning.[5]

| Muysccubun | English |

|---|---|

| aba | "maize" |

| aso | "parrot" |

| ba | "finger" or "finger tip" |

| bhosioiomy | "potato [black inside]" (species unknown) |

| chihiza | "vein" (of blood) or "root" |

| cho | "good" |

| chyscamuy | "maize [dark]" (species unknown) |

| chysquyco | "green" or "blue" |

| coca | "finger nail" |

| fo | "fox" |

| foaba | Phytolacca bogotensis, plant used as soap |

| fun | "bread" |

| funzaiomy | "potato [black]" (species unknown) |

| fusuamuy | "maize [not very coloured]" (species unknown) |

| gaca | "feather" |

| gaxie | "small" |

| gazaiomy | "potato [wide]" (species unknown) |

| guahaia | "dead body" |

| guexica | "grandfather" and "grandmother" |

| guia | "bear" or "older brother/sister" |

| hichuamuy | "maize [of rice]" (species and meaning unknown) |

| hosca | "tobacco" |

| iome | "potato" (Solanum tuberosum) |

| iomgy | "flower of potato plant" |

| iomza | "potato" (species unknown) |

| iomzaga | "potato [small]" (species unknown) |

| muyhyza | "flea" (Tunga penetrans) |

| muyhyzyso | "lizard" |

| nygua | "salt" |

| nyia | "gold" or "money" |

| phochuba | "maize [soft and red]" (species and meaning unknown) |

| pquaca | "arm" |

| pquihiza | "lightning" |

| quye | "tree" or "leaf" |

| quyecho | "arrow" |

| quyhysaiomy | "potato [floury]" (species unknown) |

| quyiomy | "potato [long]" (species unknown) |

| saca | "nose" |

| sasamuy | "maize [reddish]" (species unknown) |

| simte | "owl [white]" |

| soche | "white-tailed deer" |

| suque | "soup" |

| tyba | "hi!" (to a friend) |

| tybaiomy | "potato [yellow]" (species unknown) |

| xiua | "rain" or "lake" |

| usua | "white river clay" |

| uamuyhyca | "fish"; Eremophilus mutisii |

| xieiomy | "potato [white]" (species unknown) |

| xui | "broth" |

| ysy | "that", "those" |

| zihita | "frog" |

| zoia | "pot" |

| zysquy | "head" or "skull" |

Comparison to other Chibchan languages

| Muysccubun | Duit Boyacá |

Uwa Boyacá N. de Santander Arauca |

Barí N. de Santander |

Chimila Cesar Magdalena |

Kogui S.N. de Santa Marta |

Kuna Darien Gap |

Guaymí Panama Costa Rica |

Boruca Costa Rica |

Maléku Costa Rica |

Rama Nicaragua |

English | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chie | tia | siʔ | chibai | má | saka | sö | sö | tebej | tlijii | tukan | Moon | [13][14][15][16] |

| ata | atia | úbistia | intok | ti-tasu/nyé | kwati | éˇxi | dooka | one | [17][18] | |||

| muysca | dary | tsá | ngäbe | ochápaká | nkiikna | person man people |

[19][20] | |||||

| aba | eba | á | maize | [21][22] | ||||||||

| pquyquy | tò | heart | [23] | |||||||||

| bcasqua | yút | purkwe | to die | [24][25] | ||||||||

| uê | háta | ju | uu | house | [26][27] | |||||||

| cho | mex | morén | good | [28][29] | ||||||||

| zihita | yén | pek-pen | frog | [25][30] | ||||||||

Surviving words and education

Words of Muysccubun origin are still used in the department of Cundinamarca of which Bogotá is the capital, and the department of Boyacá, with capital Tunja. These include curuba (Colombian fruit banana passionfruit), toche (yellow oriole), guadua (a large bamboo used in construction) and tatacoa ("snake"). The Muisca descendants continue many traditional ways, such as the use of certain foods, use of coca for teas and healing rituals, and other aspects of natural ways, which are a deep part of culture in Colombia.

As the Muisca did not have words for specific things in early colonial times, they borrowed them from Spanish, such as "shoe"; çapato,[31] "sword"; espada,[32] "knife"; cuchillo[33] and other words.

The only public school in Colombia currently teaching Chibcha (to about 150 children) is in the town of Cota, about 30 kilometres (19 mi) by road from Bogotá. The school is named Jizcamox (healing with the hands) in Chibcha.

Toponyms

Most of the original Muisca names of the villages, rivers and national parks and some of the provinces in the central highlands of the Colombian Andes are kept or slightly altered. Usually the names refer to farmfields (ta), the Moon goddess Chía, her husband Sué, names of caciques, the topography of the region, built enclosures (ca) and animals of the region.[34]

References

- Chibcha at MultiTree on the Linguist List

- (in Spanish) Muysca - Spanish Dictionary

- "Chibcha Dictionary and Grammar". World Digital Library. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- Gamboa Mendoza, 2016

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 More than 2000 words in the Chibcha language

- Saravia, 2015, p.13

- Saravia, 2015, p.10

- Saravia, 2015, p.11

- González de Pérez, 2006, pp. 57–100.

- Saravia, 2015, p.12

- Saravia, 2015, p.14

- Saravia, 2015, p.15

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 Muysccubun: chie

- Casimilas Rojas, 2005, p.250

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1947, p.30

- Quesada & Rojas, 1999, p.93

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 Muysccubun: ata

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1947, p.38

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 Muysccubun: muysca

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1947, p.25

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 Muysccubun: aba

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1947, p.37

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 Muysccubun: pquyquy

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 Muysccubun: bcasqua

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1947, p.36

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 Muysccubun: uê

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1947, p.31

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 Muysccubun: cho

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1947, p.18

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 Muysccubun: zihita

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 "Shoe" in muysccubun

- (in Spanish) "Sword" in muysccubun

- (in Spanish) Diccionario muysca - español. Gómez, Diego F. 2009 - 2017 "Knife" in muysccubun

- (in Spanish) Etymology Municipalities Boyacá - Excelsio.net

Bibliography

- Casilimas Rojas, Clara Inés. 2005. Expresión de la modalidad en la lengua uwa. Amerindia 29/30. 247-262.

- Gamboa Mendoza, Jorge. 2016. Los muiscas, grupos indígenas del Nuevo Reino de Granada. Una nueva propuesta sobre su organizacíon socio-política y su evolucíon en el siglo XVI - The Muisca, indigenous groups of the New Kingdom of Granada. A new proposal on their social-political organization and their evolution in the 16th century. Museo del Oro.

- de Pérez, María Stella González. 2006. Aproximación al sistema fonético-fonológico de la lengua muisca, 53–119. Bogotá Instituto Caro y Cuervo.

- Quesada Pacheco, Miguel Ángel, and Carmen Rojas Chaves. 1999. Diccionario boruca - español, español - boruca, 1-207. Universidad de Costa Rica.

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. 1947. La lengua chimila - The Chimila language. Journal de la Société des Américanistes 36. 15-50.

- Saravia, Facundo Manuel. 2015. Curso de aproximación a la lengua chibcha o muisca - Nivel 1 - Introduction course to the Chibcha or Muisca language - Level 1, 1–81. Fundación Zaquenzipa.

Further reading

- Arango, Teresa. 1954. Precolombia: Introducción al estudio del indígena colombiano - PreColombia: Introduction to the Study of Colombian Indigenous People. Sucesores de Rivadeneyra.

- Botiva Contreras, Álvaro; Leonor Herrera; Ana Maria Groot, and Santiago Mora. 1989. Colombia prehispánica: regiones arqueológicas - Pre-Hispanic Colombia: Archeological Regions. Instituto colombiano de Antropología Colcultura.

- Martín, Rafael, and José Puentes. 2008. Culturas indígenas colombianas - Indigenous Cultures of Colombia.

- Triana, Miguel. 1922. La civilización Chibcha, 1–222.

- Wiesner García, Luis Eduardo. 2014. Etnografía muisca - Muisca Ethnography. Central Andean Region IV. 2.

External links

| Chibcha language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- (in Spanish) Diccionario y gramática chibcha - World Digital Library

- (in Spanish) Muysc cubun Project - with Muysc cubun–Spanish dictionary

- (in Spanish) Archives and sources on the Chibcha language - Rosetta Project

- (in Spanish) Animated video about the last Muisca rulers - Muysccubun is spoken with Spanish subtitles

- Muisca (Intercontinental Dictionary Series)