Django (1966 film)

Django (/ˈdʒæŋɡoʊ/, JANG-goh[5]) is a 1966 Italian Spaghetti Western film directed and co-written by Sergio Corbucci, starring Franco Nero (in his breakthrough role) as the title character alongside Loredana Nusciak, José Bódalo, Ángel Álvarez and Eduardo Fajardo.[6] The film follows a Union soldier-turned-drifter and his companion, a mixed-race prostitute, who become embroiled in a bitter, destructive feud between a gang of Confederate Red Shirts and a band of Mexican revolutionaries. Intended to capitalize on and rival the success of Sergio Leone's A Fistful of Dollars, Corbucci's film is, like Leone's, considered to be a loose, unofficial adaptation of Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo.[2][7][8]

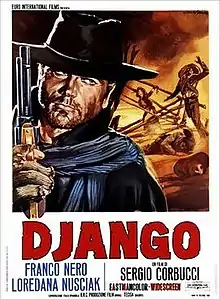

| Django | |

|---|---|

Italian film poster by Rodolfo Gasparri[1] | |

| Directed by | Sergio Corbucci |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Based on |

|

| Starring | |

| Music by | Luis Bacalov |

| Cinematography | Enzo Barboni |

| Edited by | |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | Euro International Film |

Release date |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country |

|

| Language | Italian |

| Box office | |

The film earned a reputation as one of the most violent films ever made at the time, and was subsequently refused a certificate in the United Kingdom until 1993, when it was issued an 18 certificate (the film was downgraded to a 15 certificate in 2004). A commercial success upon release, Django has garnered a large cult following outside of Italy and is widely regarded as one of the best films of the Spaghetti Western genre, with the direction, Nero's performance, and Luis Bacalov's soundtrack most frequently being praised.

Although the name is referenced in over 30 "sequels" from the time of the film's release until the early 1970s in an effort to capitalize on the success of the original, most of these films were unofficial, featuring neither Corbucci nor Nero. Nero reprised his role as Django in 1987's Django Strikes Again, the only official sequel produced with Corbucci's involvement. Nero also made a cameo appearance in Quentin Tarantino's 2012 film Django Unchained, an homage to Corbucci's original. Retrospective critics and scholars of Corbucci's Westerns have also deemed Django to be the first in the director's "Mud and Blood" trilogy, which also includes The Great Silence and The Specialists.[9]

Plot

On the Mexico–United States border, a drifter, wearing a Union uniform and dragging a coffin, witnesses Mexican bandits tying a runaway prostitute, María, to a bridge and whipping her. The bandits are dispatched by henchmen of Major Jackson – a racist ex-Confederate officer – who is preparing to kill María by crucifying her atop a burning cross. The drifter, who identifies himself as Django, easily shoots the men, and offers María protection. The pair arrive in a ghost town, populated by Nathaniel, a bartender, and five prostitutes. Nathaniel explains that the town is a neutral zone in a conflict between Jackson's Red Shirts and General Hugo Rodríguez's revolutionaries.

Jackson and his men arrive at the saloon to extract protection money from Nathaniel. Django verbally confronts two Klansmen when they harass a prostitute, and ridicules Jackson's beliefs. Django then shoots his men, and challenges Jackson to return with all of his accomplices. Afterwards, he seduces María when she thanks him for his protection.

Jackson returns with his entire gang. Using a machine gun contained in his coffin, Django guns down much of the Klan, allowing Jackson and a handful of men to escape. While helping Nathaniel bury the corpses, Django visits the grave of Mercedes Zaro, his former lover who was killed by Jackson. Hugo and his revolutionaries arrive and capture Jackson's spy, Brother Jonathan. As punishment, Hugo cuts off Jonathan's ear, forces him to eat it, and shoots him in the back. Later, Django proposes to Hugo, who he had once saved in prison, that they steal Jackson's gold, currently lodged in the Mexican Army's Fort Charriba.

Nathaniel, under the guise of bringing prostitutes for the soldiers, drives a horse cart containing Django, Hugo and four revolutionaries, two of whom are named Miguel and Ricardo, into the Fort, allowing them to massacre many of the soldiers – Miguel uses Django's machine gun, while Django, Hugo and Ricardo fight their way to the gold. As Django and the revolutionaries escape, Jackson gives chase, but is forced to stop when the thieves reach American territory. Django asks for his share of the gold, but Hugo, wanting to use it to fund his attacks on the Mexican Government, promises to pay Django once he is in power.

When Ricardo tries to force himself onto María during the post-heist party, a fight erupts between Django and Ricardo, resulting in the latter's death. Hugo allows Django to spend the night with María, but he chooses another prostitute. Django has the prostitute distract the men guarding the safehouse containing the gold, and enters the house via the chimney. Stealing the gold in his coffin and activating his machine gun as a diversion, Django loads the coffin onto a wagon. María implores Django to take her with him.

Arriving at the bridge where they first met, Django tells María that they should part ways, but María begs him to abandon the gold so they can start a new life together. When María's rifle misfires, the coffin falls into the quicksand below. Django nearly drowns when he tries to recover the gold, and María is wounded by Hugo's men while trying to save him. Miguel crushes Django's hands as punishment for being a thief, and Hugo's gang leave for Mexico. Upon arrival, the revolutionaries are massacred by Jackson and the army. Django and María return to the saloon, finding only Nathaniel there, and Django tells them that, despite his crushed hands, he must kill Jackson to prevent further bloodshed.

Jackson learns that Django is waiting for him at Tombstone Cemetery and kills Nathaniel, but not before the latter hides María. Django, resting himself on the back of Mercedes Zaro's cross, pulls the trigger guard off his revolver with his teeth and rests it against the cross, just as Jackson's gang arrive. Believing that Django cannot make the sign of the cross with his mutilated hands, Jackson shoots the corners of Zaro's cross. Django then kills Jackson and his men by pushing the trigger against the cross and repeatedly pulling back the hammer. Leaving his pistol on Zaro's cross, Django staggers out of the cemetery, ready to start a new life with María.

Cast

- Franco Nero as Django

- Nero's voice was dubbed in English by Tony Russel, whom he had previously starred alongside in Wild, Wild Planet.[10]

- José Canalejas as Hugo Gang Member

- José Bódalo as General Hugo Rodríguez

- Loredana Nusciak as María

- Angel Alvarez as Nathaniel, the Bartender

- Eduardo Fajardo as Major Jackson

- Gino Pernice (as Jimmy Douglas) as Brother Jonathan, Jackson's Spy

- Simon Arriaga as Miguel, Hugo's Henchman

- Giovanni Ivan Scratuglia as Leading Klansman at Bridge

- Remo De Angelis (as Erik Schippers) as Ricardo, Hugo's Henchman

- Raphael Abaicin as Hugo Gang Member

- Lucio De Santis as Whipping Bandit

- Silvana Bacci as Mexican Prostitute

- Guillermo Méndez as Klansman watching Jackson's target practice

- José Terrón as Ringo, Scarred Klansman

- Luciano Rossi as Klansman in Saloon

- Rafael Vaquero as Hugo Gang Member

- Cris Huerta as Mexican Officer at Fort Charriba

- Flora Carosello as Black Hair Saloon Girl

- Rolando De Santis as Klan Member

- Gilberto Galimberti as Klan Member

- Alfonso Giganti as Klan Member

- Giulio Maculani as Klan Member

- Yvonne Sanson as Redhead Saloon Girl

- Attilio Severini as Klan Member

Production

Development and writing

During the production of Ringo and his Golden Pistol, Sergio Corbucci was approached by Manolo Bolognini, an ambitious young producer who had previously worked as Pier Paolo Pasolini's production manager on The Gospel According to St. Matthew, to write and direct a Spaghetti Western that would recoup the losses of his first film as producer, The Possessed. Corbucci immediately accepted Bolognini's offer, leaving Ringo and his Golden Pistol to be completed by others. The director wanted to create a film inspired by Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo, which he had seen two years prior on recommendation from his regular cinematographer, Enzo Barboni. Corbucci also wanted to make a film that would rival the success of A Fistful of Dollars, a Yojimbo adaptation directed by his friend Sergio Leone.[2] According to Ruggero Deodato, Corbucci's assistant director, the director borrowed the idea of a protagonist who dragged a coffin behind him from a comic magazine he found on a news-stand in Via Veneto, Rome.[7]

Bolognini gave Corbucci a very short schedule in which to write the film's screenplay. The first outlines of the story were written by Corbucci with his friend Piero Vivarelli; the pair wrote backwards from the final scene of the film. The destruction of the lead character's hands prior to the final showdown was influenced by Corbucci's previous film, Minnesota Clay, which depicted a blind protagonist who attempts to overcome his disability.[2] It was also from this that the name "Django" was conceived for the hero – according to Alex Cox, Django's name is "a sick joke on the part of Corbucci and his screenwriter-brother Bruno" referencing jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt, who was known for his exceptional musicianship in spite of the fourth and fifth fingers on his left hand being paralysed.[8][11] Additionally, because Corbucci was a left-wing "political director", Cox suggests that the plot device of Django's machine gun being contained in a coffin, along with the cemetery-buried gold hunted by the lead characters of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, may have been inspired by rumours surrounding the anti-Communist Gladio terrorists, who hid many of their 138 weapons caches in cemeteries. Major Jackson's use of Mexican peons as target practice also has historical precedence – Indigenous Brazilians had been used as target practice by white slavers as late as the 1950s.[8] Corbucci is also alleged to have studied newsreel footage of the Ku Klux Klan while writing scenes featuring Major Jackson and his men, who wear red hoods and scarves in the film.[2]

Corbucci and Vivarelli's outline was then revised by Franco Rossetti.[2] By the time filming began, Corbucci was directing from a "scaletta [...] like a synopsis, but more detailed, [yet] still not a full screenplay".[12] Further screenplay contributions and revisions were made throughout production, namely by José Gutiérrez Maesso and Fernando Di Leo (who was not credited for his work on the script) and especially by Bruno Corbucci.[2] Actor Mark Damon has also claimed to have collaborated with Corbucci on the story prior to the film's production.[8] Italian prints credit the Corbucci brothers with "story, screenplay & dialogue", while Rossetti, Maesso and Vivarelli are credited as "screenplay collaborators". English prints do not list Maesso, and credit Geoffrey Copleston for the English-language script.[13]

Casting

Corbucci originally wanted to cast Mark Damon (who had played the title character of Ringo and his Golden Pistol) as Django, but Damon experienced a conflict in his scheduling and had to withdraw. Bolognini considered either Franco Nero or Peter Martell for the role, and eventually decided to have Fulvio Frizza, the head of Euro International Film (the film's distributor), choose the actor based on photographs of the three men. Frizza chose Nero, who was reluctant to appear in the film because he wanted to perform roles in more "serious" films. He was eventually persuaded by his agent, Paola Petri, and her husband, director Elio Petri, to accept the role on the grounds that he would have "nothing to lose".[7][12][14] Nero was 23 when he was cast; to give the impression of an older, Clint Eastwood-type persona, he grew out his stubble, wore fake wrinkles around his eyes, and had his voice dubbed in post-production by actor Nando Gazzolo.[15] He also asked Corbucci to have his character dressed in a black Union Army uniform as a reference to his family name (Nero means "black").[14] During filming, Corbucci invited Sergio Leone to meet Nero, who felt that the young actor would become successful.[7]

Filming

Filming began in December 1965[12] at the Tor Caldara nature reserve, near Lavinio in Italy. Most interior and exterior shots were filmed on the Elios Film set outside of Rome, which included a dilapidated Western town renovated by Carlo Simi, a veteran of both Corbucci and Leone's films.[2] Corbucci was at first dissatisfied with the muddy street of the Elios set (he initially wanted the film to be set in snowy locations, foreshadowing his work on The Great Silence), but was eventually persuaded by Bolognini and his wife, Nori Corbucci, to use the muddy locations.[2] Production halted several days after filming began to allow the Corbucci brothers to polish the script, while Bolognini secured extra financial backing from the Spanish production company Tescia.[14] Filming restarted in January, with several exteriors being filmed in Colmenar Viejo and La Pedriza of Manzanares el Real, near Madrid.[14] The final gunfight between Django and Jackson's men was filmed in Canalone di Tolfa, near the Roman Lazio area.[2] Filming concluded by late February 1966.[12] Unlike most Spaghetti Westerns, which were filmed in 2.39:1 Techniscope and printed in Technicolor, Django was filmed in the standard European widescreen (1.66:1) format and printed in Eastmancolor.[8]

In an interview for Segno Cinema magazine, Barboni explained that during the two weeks of shooting at the Elios Film set, filming was made problematic by the low amount of available sunlight. Grey and heavy clouds covered the sky nearly permanently, making it extremely difficult for the crew to choose the right light. Many scenes turned out to be underexposed, but the type of film negative that was used permitted this, and the crew was enthusiastic about the visual effects created.[2] Deodato believes that as a result of the limitations imposed by the cold weather and the low budget, as well as the craftsmanship of production members such as costumer Marcella De Marchis (the wife of Roberto Rossellini), the film has a neorealistic aesthetic comparable to the works of Rossellini and Gualtiero Jacopetti.[7] Nero has noted that Corbucci displayed a keen sense of black humour throughout production, which once resulted in the director and his crew abandoning Nero during the shooting of the film's opening titles as a joke.[12]

Soundtrack

| Django | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 1985 2 April 2013 (re-release) |

| Recorded | 1966 |

| Genre | Latin, Orchestral, Rock |

| Length | 40:16 (1985) 1:16:34 (2013) |

| Label | Generalmusic (1985) GDM Music (2013) |

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Movie Wave | |

| Sputnikmusic | |

The soundtrack for Django was composed and conducted by Luis Bacalov, known then for his score on The Gospel According to St. Matthew.[1] It was his first Western film score, and was followed several months later by his soundtrack for Damiano Damiani's A Bullet for the General, which reused several themes from his Django score.[2][8] In comparison to the contemporary classical style of Ennio Morricone's Spaghetti Western scores, Bacalov's soundtrack is more traditional, and relies especially on brass and orchestral styles of instrumentation, although several tracks use distinctive elements of Latin and rock music.[1][8] The main titles theme, which was conducted by Bruno Nicolai and features lyrics by Franco Migliacci and Robert Mellin,[16] was sung in English for the film by Rocky Roberts. An Italian version of the song, released only on the soundtrack album and as a single, was performed by Roberto Fia.[17] The soundtrack album, originally released in 1985, was re-released in 2013 with a new song listing and additional tracks.

Original vinyl release, 1985:[18]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Release and reception

Django received an 18 certificate in Italy due to its then-extreme violence. Bolognini has stated that Corbucci "forgot" to cut the ear-severing scene when the Italian censors requested he remove it.[2][8] The film was commercially successful, earning 1,026,084,000 lire in Italy alone during its theatrical run.[19]

In the United States, Django was shown for a brief period in Los Angeles during the making of Nero's first production in Hollywood, Camelot; this limited release consisted of four screenings that were hosted by Nero himself.[20] Although Jack Nicholson attempted to buy the American rights to the film in 1967,[1] Django did not find a legitimate distributor in the US until 1972, when it was released in an edited form by Jack Vaughan Productions as Jango.[1][21] On December 21, 2012, Rialto Pictures and Blue Underground re-released Django in dubbed and subtitled form in selected theatres to coincide with the release of Quentin Tarantino's Django Unchained. By February 7, 2013, this release had earned $25,916 at the box office.[4][22]

In Japan, Django was released by Toho-Towa as Continuation: Wilderness Bodyguard (続・荒野の用心棒, Zoku・kōya no yōjinbō),[23] presenting the film as not only a remake of Yojimbo (用心棒, Yōjinbō), but as a sequel to A Fistful of Dollars (荒野の用心棒, Kōya no yōjinbō), which had been distributed in Japan by Toho-Towa on behalf of Akira Kurosawa.[24]

Critical response

Although initial critical reactions to the film were negative due to the high level of violence,[7] reception of Django in the years following its original release has been very positive, with the film gaining a 92% "fresh" score on Rotten Tomatoes based on twelve reviews, with an average rating of 8.1/10.[25] The film is generally ranked highly on lists of Spaghetti Western films considered to be the best, and along with Corbucci's own The Great Silence, it is often viewed as one of the best films of the genre to have not been directed by Sergio Leone.[26][27][28][29][30][31] Corbucci's direction, Bacalov's score and Nero's role are among the most-praised elements of the film. However, the English-dubbed version has frequently been criticized for being inferior, voice acting and script-wise, to the Italian version.[1][8]

In a contemporary review of the film for the Italian newspaper Unita, Django's depiction of violence was described as "the heart of the story", "truly bloodcurdling", and "dismayingly justified in the emotions of the audience". The reviewer also noted that, "this repetition of excessive cruelty, in its sheer extent and verisimilitude, transfers the film from a realistic plane to the grotesque, with the result that here and there it is possible to find, among the emotions, a certain healthy amount of humour".[32]

When reviewing the film for Monthly Film Bulletin, film historian Sir Christopher Frayling identified Django's attire, including "his Sunday-best soldier's trousers, worn-out boots and working man's vest", as a major aspect of the film's success on the home market. According to Frayling, Django's appearance makes him appear "less like an archetypal Western hero than one of the contadini (farmers) on his way back from the fields, with working tools on his back, dragging his belongings behind him, [making a] direct [point] of contact with the Southern Italian audiences".[8] Reactions to Nero's limited screenings of Django in Los Angeles, compared to the responses of Italian critics, were highly enthusiastic. Audience members, which included actors and filmmakers such as Paul Newman, Steve McQueen and Terence Young, were appreciative of the film's sense of humour and originality.[7][20]

Budd Wilkins, reviewing Django for Slant Magazine during its 2012 theatrical re-release, rated the film three-and-a-half stars out of four, and compared its aesthetics and story to the "rough-hewn storytelling and rough-and-tumble pessimism that characterize subsequent Corbucci films like The Great Silence" and the "political dimension" of "more radicalized Zapata Westerns like Damiano Damiani's A Bullet for the General". Describing the film as an "unrepentantly ugly movie, despite the striking visual flair Corbucci brings to his blocking and camera movement", Wilkins compared the film's "appalling" depictions of violence and sadomasochism to Marlon Brando's One-Eyed Jacks, "except Corbucci carries things far beyond the bloody horsewhipping Brando's Rio receives in that film". He concluded his review by stating that, "in a genre known for endless knock-offs, a trend that includes Django's 30-plus sequels, Corbucci's film is notable not only for the artistry of its construction, but also for the underlying anger that fuels its political agenda".[33]

In his analysis of the Spaghetti Western genre, Alex Cox described Django as a "huge step forward" in Corbucci's writing and directing abilities, exemplified by the film's pacing and action scenes (comparable to those of a James Bond film) and its dropping of the "unsteady, often boring narratives, bad transitions, ‘cute/funny' characters, and tedious horse-riding-through-landscape scenes" that permeated his previous Westerns. Cox voiced praise for Enzo Barboni's "claustrophobic" and "brutal, uncompromising style" of cinematography, including "some striking wide-angle establishing shots" and "a good hand-held fight scene", and described Carlo Simi's work on the Elios Film set as "a masterpiece of low-budget art direction […] a town with no name, a battleground where there is literally nothing worth fighting for". Performance-wise, he noted that Nero's performance as Django is "almost entirely taciturn: vulnerable, angelic, strangely robotic. Loredana Nusciak plays María the same way: emotionless, inert, and – once she gets hold of a rifle – merciless. Nero and Nusciak are the only cast members who don't overact. Yet each character's silence seems not to be innate, but learned, a result of endless proximity to mindless violence". He theorized that the two characters suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder due to their constant exposure to violence, and thus make a "perfect" romantic couple. Cox also found that the film's upbeat ending, a rarity in Spaghetti Western films, "tells us something of Corbucci's fondness for women, and for personal bonds".[8]

UK BBFC ban

When Butcher's Film Service submitted Django to the British Board of Film Censors in 1967, examiners recommended that the film be denied classification and banned outright. The company appealed to the Board's Secretary, John Trevelyan, who concurred with the assessment of examiners that the film's "excessive and nauseating violence" was justification for its denial of a certificate. More importantly, he explained that it would not be possible to cut the film for an X rating.[34][35]

In 1972, Django was offered to another distributor, who asked the new BBFC Secretary, Stephen Murphy, whether the film could be passed. Murphy suggested that it would still be unlikely for the film to receive a certificate, largely because of both the Board's scathing 1967 assessment of the film and the "sensitivity of critics" to depictions of violence in films such as Straw Dogs. Ultimately, the distributor chose not to acquire the film. In 1974, a new distributor decided to re-submit the film for classification. Examiners were divided over whether the film could be passed with cuts, especially given the raising of the minimum age for X films from 16 to 18 in 1971. However, it was concluded that the film's "loving dwelling on violence", which was viewed by the Board as its "sole raison d'etre", meant that the 1967 rejection was still justified. Rather than being formally rejected again, Django was withdrawn from classification by the distributor.[35][36] Before the introduction of the Video Recordings Act 1984, the film was unofficially released at least twice on pre-certification video, but was never seized or prosecuted during the video nasties panic.[37][38]

Django did not receive a classification in the UK until it was submitted for an official video release by Arthouse Productions in 1993, when the BBFC concluded it could be passed, without cuts, with an 18 certificate.[39] The examiner report stated that "Although two decades ago the feature may have seemed mindless violence, in the age of Terminator 2 and Arnold Schwarzenegger, the feature has an almost naive and innocent quality to it [...] One could say that the feature is almost bloodless".[35][36] Django made its official UK première on August 1, 1993 at 9:50 pm on BBC2's Moviedrome block, where the film was introduced by Alex Cox.[11]

Five specific scenes were called into question in both the 1974 and 1993 examiner reports of the film:[35][36]

- María's whipping by Mexican bandits, which was the primary reason for the 18 rating in 1993. The scene was passed without cuts because the action was found to be neither sexualized nor titillating.

- The severing of Brother Jonathan's ear was eventually accepted because the wound itself is never shown.

- Miguel's crushing of Django's hands was passed in 1993 due to few shots of the sequence actually featuring Django's hands.

- Two separate horsefalls were deemed to not be in breach of the Board's policy on animal cruelty, due to one of the falls taking place on soft mud, and the other being on the horse's side.

Django was examined by the BBFC for a fourth time in 2004, when Argent Films submitted the film prior to its British DVD release. The film was downgraded to a 15 certificate for "moderate bloody violence". The BBFC have acknowledged that the original 18 certificate was partially reactionary to the film's censorship history.[35]

Home media

Django was first released on DVD in the US as a double feature with Django Strikes Again on September 24, 2002. This release, by Anchor Bay Entertainment, is mostly uncut and presented with a remix of the English dub in Dolby Digital 5.1 surround sound, and was limited to 15,000 copies. Included as special features are trailers for the two films, exclusive interviews with Nero about their production histories, an arcade-style interactive game and an illustrated booklet with essays on the films. This release, which is currently out of print, was criticized for its hazy, washed-out transfer.[40] Prior to the original DVD release, Anchor Bay had released both films on VHS in 1999.[41][42]

On January 7, 2003, Blue Underground, having acquired the distribution rights to Django from Anchor Bay, released a second DVD of the film as part of The Spaghetti Western Collection boxset, which also included the films Django Kill... If You Live, Shoot!, Run, Man, Run and Mannaja: A Man Called Blade.[40] A standalone two-disc limited edition version was released on April 27, 2004, with the first disc containing the film and the second containing Alessandro Dominici's The Last Pistolero, a short film starring Nero in a tribute to his Western film roles. A third DVD release, made available on July 24, 2007, omitted The Last Pistolero.[43]

Blue Underground's DVD releases utilize a high quality (albeit mildly damaged) transfer based on the film's original camera negative, which was subject to a complex two-year digital restoration process that resulted in many instances of dirt, scratches, warps and deteriorations being removed and corrected.[44] The DVD, which presents Django completely uncut with Dolby Digital mono mixes of both the English and Italian dubs (as well as English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue), includes the film's English trailer, Django: The One and Only (an interview piece with Nero and Ruggero Deodato), a gallery of poster and production art compiled by Ally Lamaj, and talent biographies for Nero and Corbucci.[44] A Blu-ray release, featuring a revised high definition transfer of the negative and DTS-HD Master Audio Mono mixes of the English and Italian dubs, was released by Blue Underground on May 25, 2010. Unlike most of Blue Underground's releases, which are Region 0 or Region Free-encoded, the Django Blu-ray is Region A-locked.[40] The original DVD was included, along with Django Kill... If You Live, Shoot!, Keoma and Texas, Adios, as part of a four-disc set titled Spaghetti Westerns Unchained on May 21, 2013.[43]

In the UK, Argent Films released Django on DVD in 2004.[34] This release, which features exclusive interviews with Nero and Alex Cox, was re-released on September 1, 2008, and was later included in Argent's Cult Spaghetti Westerns boxset alongside Keoma and A Bullet for the General, released on June 21, 2010.[45] Argent later released its own Blu-ray, also taken from the original negative, on January 21, 2013, alongside a remastered DVD based on the same transfer.[45]

On September 1, 2018, Arrow Video announced that they would release Django on November 19 (later pushed back to December 11) in the US and Canada as part of a two-disc Blu-ray set with Texas, Adios, with the films having received new 4K and 2K restorations respectively. The special features for the film include an audio commentary by Stephen Prince, new interviews with Nero, Deodato, Rossetti, and Nori Corbucci, archival interviews with Vivarelli and stunt performer Gilberto Galimberti, an appreciation of Django by Spaghetti Western scholar Austin Fisher, an archival introduction to the film by Cox, and the theatrical trailer. Two versions of this release were revealed in this announcement: a standard edition that would also include an illustrated liner notes booklet featuring a new essay by Spaghetti Western scholar Howard Hughes and reprintings of contemporary reviews of the film, as well as a double-sided poster; and a steelbook edition that would not include the poster.[46][47] Prior to their intended release, Arrow withdrew both editions from their catalogue pending the outcome of a rights dispute between Blue Underground (who claimed to still have sole ownership of the film's US distribution rights, and had sent cease and desist letters to consumers who had pre-ordered the titles) and the film's Italian rights holder Surf Film (from whom Arrow obtained permission to release both films in February that year).[48] After 2 years, the Arrow edition will finally see release on June 30, 2020.

Sequels

More than thirty unofficial "sequels" to Django have been produced since 1966. Most of these films have nothing to do with Corbucci's original film, but the unofficial sequels copy the look and attitude of the central character.[2] Among the most well-received of the unofficial sequels are Django Kill... If You Live, Shoot! (starring Tomas Milian), Ten Thousand Dollars for a Massacre (starring Gianni Garko and Loredana Nusciak), Django, Prepare a Coffin (produced by Manolo Bolognini and starring Terence Hill in a role originally intended for Franco Nero) and Django the Bastard (starring Anthony Steffen).[1]

An official sequel, Django Strikes Again, was released in 1987 with Nero reprising his role as the title character.[1]

In December 2012 a third official sequel, titled "Django Lives!" was announced with Franco Nero reprising his role as the title character. The film would follow Django in his twilight years participating as a consultant on silent westerns in 1915 Hollywood. Nero signed on to reprise his role after reading the script, penned by Eric Zaldivar and Mike Malloy, and Robert Yeoman, long time cinematographer for director Wes Anderson, was attached as Director of Photography.[49][50]

In April 2015, an English-language television series based on Django was announced as being developed as an Italian-French co-production by Atlantique Productions and Cattleya. The series was slated to consist of 12 fifty-minute-long episodes, with the possibility of multiple seasons.[51][52][53][54][55][56]

In May 2016, it was reported that the script for "Django Lives" was purchased and rewritten by director John Sayles. The plot still appears to take place in 1915's Hollywood and will possibly be directed by Christian Alvart.[57]

Legacy

The lead character's iconic coffin arsenal has been paid homage in several movies and TV series, including several Japanese anime series. Fist of the North Star features a plot device wherein the lead character, Kenshiro, drags a coffin behind him into a wasteland town. In the Cowboy Bebop episode, "Mushroom Samba", a bounty hunter runs around with a coffin behind him. The character Wolfwood in Trigun has a cross-shaped arsenal case called the Punisher which he carries frequently that is reminiscent of Django's coffin. The character Beyond The Grave (formerly Brandon Heat), of Gungrave, carries a metal coffin-shaped device which houses a variety of weapons. The fantasy movie Death Trance features a protagonist dragging a sealed coffin around for much of the film. In the Brazilian pornochanchada film Um Pistoleiro Chamado Papaco (A Gunman Called Papaco), the title character spends the whole film carrying a coffin and the opening scene is inspired by Corbucci's film. The main character of the Boktai series of video games is a vampire hunter named Django, who drags a coffin around for sealing and purifying immortals. In the video game Red Dead Revolver, the boss Mr. Black carries around a coffin that houses a Gatling Gun.

Django is the inspiration for the 1969 song and album Return of Django by the Jamaican reggae group the Upsetters. Additionally, Django is the subject of the song "Django" on the 2003 Rancid album Indestructible. The music video for the Danzig song "Crawl Across Your Killing Floor" is inspired by the film and shows Glenn Danzig dragging a coffin.[58]

According to Nero, former James Bond director Terence Young was inspired by Django to direct the Western Red Sun, an international co-production starring Charles Bronson, Toshirō Mifune (of Yojimbo fame), Ursula Andress and Alain Delon.[7]

The 1972 Jamaican film, The Harder They Come, contains a sequence where the hero, Ivan, watches Django in a cinema, which has echoes with his character and story.[11]

Takashi Miike's 2007 film, Sukiyaki Western Django, is a highly stylized Western film inspired by Django, Yojimbo and A Fistful of Dollars.[59]

Anti Hero in Dennou Keisatsu Cybercop, Lucifer was based on Django portrayal, gunslinger, wandering around in cowboy hat, all black clothes, also good at quick draw, most notably when he were introduced in Django styled carrying a coffin with him and keep his weapon in it.

Quentin Tarantino's 2012 film Django Unchained pays several tributes to Corbucci's film. In Unchained, Nero plays a small role as Amerigo Vessepi, the owner of a slave engaged in Mandingo fighting with a slave owned by Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio). Upon the loss of that fight, Vessepi goes to the bar for a drink and encounters Django, played by Jamie Foxx. Vessepi asks Django what his name is and how it is spelt, and upon Django's informing him that the "D" is silent, says "I know."[60] Django Unchained also uses the Rocky Roberts-Luis Bacalov title song (along with several score pieces) from the original film;[61] the film's end credits theme, "Ode to Django (The D Is Silent)", performed by RZA, uses several dialogue samples from Django's English dub, most prominently María's line "I love you, Django".[62] Tarantino had previously referenced Corbucci's film in Reservoir Dogs; the scene in which Brother Jonathan's ear is severed by Hugo was the inspiration for the scene in which Vic Vega does the same to Nash.[33]

References

- Hughes, 2009

- Giusti, 2007

- "Django Box Office". Box Office Story. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- "Django (2012 re-release)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- The "d" is silent.

- "Once Upon a Time in Italy - A Spaghetti Western Roundup at Film Forum". The New York Times. 2012-06-03. Retrieved 2012-06-12.

- Django (Django: The One and Only) (DVD). Los Angeles, California: Blue Underground. 1966.

- Cox, 2009

- Hughes, Howard (2020). Western Excess: Sergio Corbucci and The Specialists (booklet). Eureka Entertainment. p. 8. EKA70382.

- Taylor, 2015

- "Moviedrome - Django". YouTube. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- O'Neill, Phelim (2011-05-26). "Franco Nero: No escaping Django". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- Django (DVD). London, United Kingdom: Argent Films. 1966.

- "FRANCO NERO - Interview discussing the making of DJANGO (1966)". YouTube. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "Django". Il mondo dei doppiatori, AntonioGenna.net. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "Luis Bacalov – Django - Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (German)". Discogs. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- "Luis Bacalov – Django". Discogs. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- "Luis Bacalov – Django - Original Motion Picture Soundtrack". Discogs. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- Fisher, 2014

- "Original 'Django' Franco Nero on His Iconic Character and the Film's Legacy (Q&A)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- "Jango (1972)". FilmRatings.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "Django". Rialto Pictures. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- Django ( Django (Poster & Still Gallery)) (DVD). Los Angeles, California: Blue Underground. 1966.

- A Fistful of Dollars (The Christopher Frayling Archives: A Fistful of Dollars) (Blu-ray). Los Angeles, California: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. 1967.

- "DJANGO (1966)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- "Essential Top 20 Films". Spaghetti Western Database. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "Alex Cox's Top 20 Favourite Spaghetti Westerns". Spaghetti Western Database. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "Howard Hughes' Top 20". Spaghetti Western Database. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "Quentin Tarantino's Top 20 favorite Spaghetti Westerns". Spaghetti Western Database. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "The 20 Best Spaghetti Westerns Ever Made". Hollywood.com. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- "The 30 Greatest Westerns In Cinema History". Taste of Cinema. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- "Django – a contemporary review". The Wild Eye. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- "Django". Slant Magazine. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- "DJANGO (1967)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "BBFC Podcast Episode 30 - Django (1967)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "Case Studies - Django (1967)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- "Django 1966 (Derann)". Pre-cert Video. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- "Django 1966 (Inter-Ocean)". Pre-cert Video. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- "BBFC Banned Cinema Films - Since 1960". Melon Farmers. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- "Django". DVD Beaver. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- "Django [VHS]". Amazon.com. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- "Django 2: Strikes Again [VHS]". Amazon.com. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- "Western". Blue Underground. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- "Django (1966)". Rewind @ dvdcompare.net. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- "Search results for Django". Movie Mail UK. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- "Django / Texas Adios Blu-ray Announcement" Check

|url=value (help). Facebook. Retrieved December 14, 2018. - "Django / Texas Adios Steelbook Blu-ray Announcement" Check

|url=value (help). Facebook. Retrieved December 14, 2018. - "Django / Texas Adios Ltd Ed Update". Arrow Video. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- https://www.sacurrent.com/ArtSlut/archives/2013/07/19/django-lives-franco-nero-and-sa-locals-spearhead-new-film

- https://www.slashfilm.com/the-original-django-franco-nero-attached-to-star-in-django-lives-quentin-tarantino-explains-the-django-legacy/

- Jean Pierre Diez (April 9, 2015). "Italian cult films 'Django' and Dario Argento's 'Suspiria' to be adapted for television". Sound On Sight. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- Harry Fletcher (April 9, 2015). "TV series based on 1966 western Django in the works". Digital Spy. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- Kevin Jagernauth (April 8, 2015). "'Django' And 'Suspiria' TV Shows In Development". The Playlist. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- Ryan Lattanzio (April 8, 2015). "'Django' and Dario Argento's 'Suspiria' Getting Classy TV Series Remakes". Thompson on Hollywood. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- James White (April 8, 2015). "Sergio Corbucci's Django Heads For TV". Empire Magazine. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- Nick Vivarelli (April 8, 2015). "'Django' And Dario Argento's 'Suspiria' To Be Adapted Into International TV Series". Variety. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- "John Sayles to Direct Django Lives!". The Action Elite. 2016-05-23. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- Harris, Chris (September 8, 2006). "Danzig Unearths Lost Tracks". MTV.com. Retrieved 2013-02-26.

- Lindsay, Cam. "TIFF Reviews: Sukiyaki Western: Django". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16.

- "Quentin Tarantino, 'Unchained' And Unruly". Retrieved 2013-01-23.

- "Various - Django Unchained (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)". Discogs. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- Django Unchained (DVD). Culver City, California: Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. 2012.

Bibliography

- Cox, Alex (2009). 10,000 Ways to Die: A Director's Take on the Spaghetti Western. Oldcastle Books. ISBN 978-1842433041.

- Fisher, Austin (2014). Radical Frontiers in the Spaghetti Western: Politics, Violence and Popular Italian Cinema. I.B.Tauris. p. 220. ISBN 9781780767116.

- Giusti, Marco (2007). Dizionario del western all'italiana. Mondadori. ISBN 978-88-04-57277-0.

- Hughes, Howard (2009). Once Upon A Time in the Italian West: The Filmgoers' Guide to Spaghetti Westerns. I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85043-896-0.

- Taylor, Tadhg (2015). Masters of the Shoot-'Em-Up: Conversations with Directors, Actors and Writers of Vintage Action Movies and Television Shows. McFarland. p. 220. ISBN 9780786494064.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Django (1966 film) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Django (film). |

- Django at IMDb

- Django at the TCM Movie Database

- Django at Rotten Tomatoes

- Django at AllMovie

- Django (2012 re-release) at Box Office Mojo

- Django at Surf Film

- Django at The Spaghetti Western Database (SWDb)