Electrophone (information system)

The Electrophone was a distributed audio system that operated in the United Kingdom, primarily in London, between 1895 and 1925. Using conventional telephone lines, it relayed live theatre performances, music hall shows, and Sunday church services to subscribers who listened over special headsets. It ultimately failed due to the rise of radio broadcasting in the early 1920s.

History

The Electrophone was preceded by the similarly organized Théâtrophone system of Paris, France, which began operation in 1890. In 1894, Mr. H. S. J. Booth formed the Electrophone Company, Ltd. with an initial capitalization of £20,000,[2] and the service began operations in London the next year, with Booth acting as the Managing Director. Initially the company operated under a licence issued by the National Telephone Company.

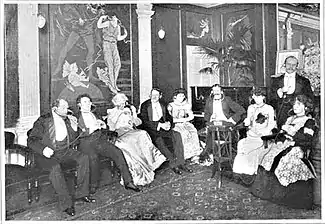

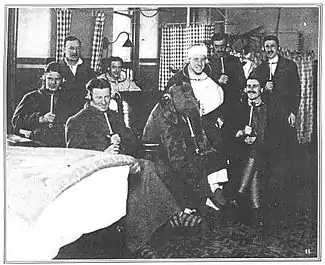

To pick up the programmes, multiple large carbon microphones were placed in the theatre footlights to pick up the sounds of the performers. In churches, the microphones were disguised to look similar to bibles. Home subscribers were issued headphones that connected to their standard telephone lines. The annual charge was £5, which limited its affordability to the well-to-do. Queen Victoria was a subscriber.[4] In 1897 it was noted that coin-operated receivers had been installed in some hotels, which provided a few minutes of entertainment for a sixpence.[5] Additional lines were installed, for free, for use by convalescing hospital patients.[3]

A special manual switchboard, located at the Electrophone building in Pelican House on Gerrard Street, London, provided links to the participating entertainment establishments and churches. Subscribers called Electrophone operators to have their lines connected to the site they selected. Subscribers with two telephone lines could use the second line to make a request to change the site during the course of an evening. A 1906 advertisement stated that they could choose from among fourteen theatres — the Aldwych, Alhambra, Apollo, Daly's, Drury Lane, Empire, Gaiety, Lyric, Palace, Pavilion, Prince of Wales's, Savoy, Shaftesbury and Tivoli — in addition to concerts from the Queen's and Royal Albert Halls, and, on Sundays, services from fifteen churches. [6]

In 1912, telephone operations were transferred to the control of the General Post Office. The Electrophone paid to the Postmaster General an annual fee of £25 plus a royalty of half a crown per subscriber. In 1920, the service received £11,868 from subscribers, with operating expenses of £5,866, including a £496 royalty payment to the Post Office. Theatres were paid 10 shillings annually for each connected subscriber.[7]

Although fairly long-lived, the Electrophone never advanced beyond a limited audience. In 1896 there were just 50 subscribers, although this increased to over 1,000 by 1919, and just over 2,000 at its peak in 1923. However, competition due to the introduction of radio broadcasting resulted in a rapid decline, falling to 1,000 by November 1924. In early 1923 an Electrophone director was quoted as saying that "it would be a long time before broadcasting by wireless of entertainments and church services attained the degree of perfection now achieved by the electrophone."[8] However, that proved to be overly optimistic, and as of June 30, 1925, the London Electrophone ceased operations.[9] Note the use of the word "wireless" to refer to radio transmission, as opposed to the "hard wired" transmission of the Electrophone.

A second, much smaller, system was established in Bournemouth in 1903, but the maximum number of subscribers reached only 62 by 1924. This system was finally discontinued in 1938, after it was determined during the previous year that there were only two remaining subscribers.[10]

See also

References

- "Telephone London" by Henry Thompson, in London Living: Vol. III, edited by George R. Sims, 1903, page 115.

- "The Pleasure Telephone" by Asa Briggs, from The Social Impact of the Telephone, Ithiel de Sola, Editor, 1997, page 41.

- "British Wounded Hear London's Musical Favorites", Musical America, June 9, 1917, page 17.

- "The Queen and the Electrophone", The Electrician, 26 May 1899, page 144.

- "The Electrophone" by J. Wright, The Electrical Engineer, 10 September 1897, page 344.

- "Cable Radio — Victorian Style" by Denys Parsons, New Scientist, 30 December 1982, page 794.

- Parsons (1982), pages 795-796.

- "Entertainment by Wireless: The Future of the Electrophone", The Times, 10 January 1923, page 8.

- "Electrophone, Ltd.", The Times, 17 June 1925, page 18.

- Parsons (1982), page 796.

External links

- "Cable Radio — Victorian Style" by Denys Parsons, New Scientist, 30 December 1982, pages 794-797.

- News and Entertainment by Telephone

- BBC - The 19th Century iPhone

- "The Pleasure Telephone" - BBC radio documentary