Semaphore

Semaphore is the use of an apparatus with telegraphy to create a visual signal transmitted over long-distances.[1][2] A semaphore can be performed with devices including: fire, lights, flags, sunlight and moving arms.[1][2][3]

Fire

The Phryctoriae was a semaphore system used in Ancient Greece for the transmission of specific prearranged messages. Towers were built on selected mountaintops, so that one tower, the phryctoria, would be visible to the next tower, usually twenty-miles distant. Flames were lit on one tower, then the next tower would light a flame in succession.

The Byzantine beacon system was a semaphore developed in the 9th century during the Arab–Byzantine wars. The Byzantine Empire used a system of beacons to transmit messages from the border with the Abbasid Caliphate across Asia Minor to the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. The main line of beacons stretched over some 720 km (450 mi) with stations placed from 97 km (60 mi) to 56 km (35 mi). A message could be sent along the line in approximately one hour. A bonfire was set at the first beacon and transmitted down the line to Constantinople.

The Lighthouse of Alexandria was a high tower 100 metres (330 ft) in overall height with a fire on top to provide a navigation beacon for ships in ancient times.[4] The lighthouse was built in the 2nd century BC and is considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, which remained one of the tallest man-made structures in the world for several centuries.[5] The Tower of Hercules at A Coruña, Spain was a Roman 2nd century lighthouse that used a large fire as a warning beacon to passing ships.

A smoke signal is one of the oldest forms of semaphore for long-distance communication. The smoke is used to transmit news, signal danger or gather people to a common area.

Lights

A signal lamp is a semaphore system using a visual signaling device, often utilizing Morse code. In the 19th century, the Royal Navy began using signal lamps. In 1867, then Captain, later Vice Admiral, Philip Howard Colomb for the first time began using dots and dashes from a signal lamp.[6]

The modern lighthouse is a semaphore using a tower, building, or another type of structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a navigational aid for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways. Lighthouses mark dangerous coastlines, hazardous shoals, reefs, rocks, and safe entries to harbors; they also assist in aerial navigation. Originally lit by open fires and later candles, the Argand hollow wick lamp and parabolic reflector were introduced in the late 18th century. The source of light is called the "lamp" and the light is concentrated, by the "lens" or "optic". Whale oil was also used with wicks as the source of light. Kerosene became popular in the 1870s and electricity and carbide (acetylene gas) began replacing kerosene around the turn of the 20th century. Carbide was promoted by the Dalén light which automatically lit the lamp at nightfall and extinguished it at dawn. The advent of electrification and automatic lamp changers began to make lighthouse keepers obsolete. Improvements in maritime navigation and safety with satellite navigation systems like the Global Positioning System (GPS) have led to the phasing out of non-automated lighthouses across the world.[7]

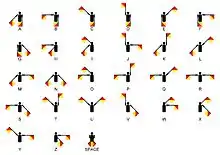

Flags

A flag semaphore is the telegraphy system conveying information at a distance by means of visual signals with hand-held flags, rods, disks, paddles, or occasionally bare or gloved hands. Information is encoded by the position of the flags.[8] It is still used during underway replenishment at sea and is acceptable for emergency communication in daylight or using lighted wands instead of flags, at night.

Sunlight

A heliograph is a semaphore that signals by flashes of sunlight using a mirror, often in Morse code. The flashes are produced by momentarily pivoting the mirror or by interrupting the sunlight with a shutter.[9] The heliograph was a simple but effective instrument for instantaneous optical communication over long distances during the late 19th and early 20th century.[9] The main uses were for the military, survey and forest protection work. Heliographs were standard issue in the British and Australian armies until the 1960s and were used by the Pakistani army as late as 1975.[10]

Moving arms

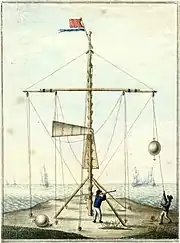

Optical telegraph

In 1792 Claude Chappe, a clergyman from France, invented a terrestrial semaphore telegraph, which uses pivoted indicator arms and conveys information according to the direction the indicators point and was popular in the late eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries.[11][12][13][1][14] Relay towers were built with a sightline to each tower at separations of 5–20 miles (8–32 km). On the top of each tower was an apparatus, which uses pivoted indicator arms and conveys information according to the direction the indicators point. An observer at each tower would watch the neighbouring tower through a telescope and when the semaphore arms began to move spelling out a message, they would pass the message on to the next tower. This early form of telegraph system was much more effective and efficient than post riders for conveying a message over long distances. The sightline between relay stations was limited by geography and weather. In addition, the visual communication would not be able cross large bodies of water.

An example is during the Napoleonic era, stations were constructed to send and receive messages using the coined term Napoleonic semaphore.[15][16] This form of visual communication was so effective that messages that normally took days to communicate could now be transmitted in mere hours.[15]

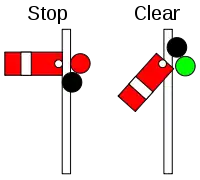

Railway signal

The Railway semaphore signal is one of the earliest forms of fixed railway signals.[17] These signals display their different indications to train drivers by changing the angle of inclination of a pivoted 'arms'.[2] A single arm that pivots is attached to a vertical post and can take one of three positions. The horizontal position indicates stop, the vertical means all clear and the inclined indicates go ahead under control, but expect to stop.[2] Designs have altered over the intervening years and colour light signals have replaced semaphore signals in most countries.

Hydraulic

Decline

In the early 1800s, the electrical telegraph was gradually invented allowing a message to be sent over a wire.[18][19] In 1835, the American inventor Samuel Morse created a dots and dashes language system representing both letters and numbers, called the Morse code. In 1837, the British inventors William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone obtained a patent for the first commercially viable telegraph.[20] By the 1840s, with the combination of the telegraph and Morse code, the semaphore system was replaced.[21] The telegraph continued to be used commercially for over 100 years and is still used by amateur radio enthusiasts. Telecommunication evolved replacing the electric telegraph with the advent of wireless telegraphy, teleprinter, telephone, radio, television, satellite, mobile phone, Internet and broadband.[22][23]

Further reading

- Burns, R.W. (2003). Communications: An International History of the Formative Years. (Chapter 2) The Institution of Engineering and Technology. ISBN 978-0863413278

- Holzmann, Gerard J. (1994). The Early History of Data Networks. Wiley-IEEE Computer Society Press; 1st edition. ISBN 978-0818667824

- Pasley, C. W. (1823). Description of the Universal Telegraph for Day and Night Signals. T. Egerton Military Library. Egerton.

- Wilson, G. (1976). The Old Telegraphs. Phillimore & Co. Chichester, West Sussex. ISBN 978-0900592799

References

- Encyclopedia Britannica – Semaphore

- The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed. – Semaphore

- Beauchamp, K. G. (2001). History of Telegraphy. (Chapter 1). The Institution of Engineering and Technology. ISBN 978-0852967928

- Clayton, Peter A. (2013). "Chapter 7: The Pharos at Alexandria". In Peter A. Clayton; Martin J. Price (eds.). The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. London: Routledge. p. 147. ISBN 9781135629281.

- Clayton, Peter A. (2013). "Chapter 7: The Pharos at Alexandria". In Peter A. Clayton; Martin J. Price (eds.). The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. London: Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 9781135629281.

- Sterling, Christopher H. (ed.). Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-85109-732-6.

- "Maritime Heritage Program – National Park Service". Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- "History of Semaphore" (PDF). Royal Navy Communications Branch Museum/Library. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Woods, Daniel (2008). "Heliograph and Mirrors". In Sterling, Christopher (ed.). Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century. ABC-CLIO. p. 208. ISBN 978-1851097326.

- Major J. D. Harris WIRE AT WAR – Signals communication in the South African War 1899–1902. Retrieved on 1 June 2008. Discussion of heliograph use in the Boer War.

- Burns, R. W. (2004). "Chapter 2: Semaphore Signalling". Communications: an international history of the formative years. ISBN 978-0-86341-327-8.

- "Telegraph". Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (6th ed.). 1824. pp. 645–651.

- David Brewster, ed. (1832). "Telegraph". The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia. 17. pp. 664–667.

- J-M. Dilhac, "The Telegraph of Claude Chappe: An Optical Telecommunication Network for the XVIIIrd Century."

- "How Napoleon's semaphore telegraph changed the world". BBC News. 2013-06-16. Retrieved 2020-12-23.

- Napoleonic Telecommunications: The Chappe Semaphore Telegraph

- "The Origin of the Railway Semaphore". Mysite.du.edu. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- Moss, Stephen (10 July 2013), "Final telegram to be sent. STOP", The Guardian: International Edition

- Standage, Tom. (2014). The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century's On-line Pioneers. Bloomsbury USA; Second Edition, Revised. ISBN 9781620405925

- Beauchamp, K. G. (2001). History of Telegraphy. (Chapter 3). The Institution of Engineering and Technology. ISBN 978-0852967928

- Encyclopedia Britannica – The End Of The Telegraph Era

- "Article 1.3" (PDF), ITU Radio Regulations, International Telecommunication Union, 2012, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2015

- Constitution and Convention of the International Telecommunication Union, Annex (Geneva, 1992)

External links

Media related to Semaphore at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Semaphore at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of semaphore at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of semaphore at Wiktionary- YouTube: TeleCommunication: Semaphore Systems

- YouTube: Information Theory part 4: Semaphores & signal fires

- Youtube: 2nd March 1791: Claude Chappe sends the first message by semaphore machine