Estonia–Russia border

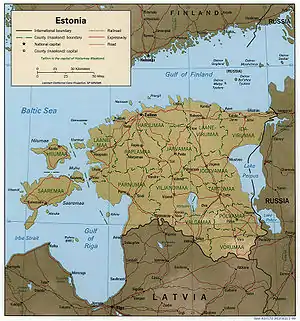

The Estonia–Russia border is the international border between Republic of Estonia (EU member) and the Russian Federation (CIS member). The border is 294 kilometres (183 mi) long. It appeared in 1918 once Estonia declared its independence from Russia. The border goes mostly along the national, administrative and ethnic boundaries that have gradually formed since XIII century. The exact location of the border was a subject of Estonian-Russian dispute that was resolved with the signing of the Border Agreement, but neither Russia nor Estonia have completed its ratification yet.[1]

History

Origins of the border

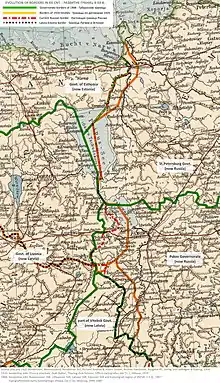

Until XIII century no strict borders existed between Baltic, Slavic and Finnic peoples that populated North-Eastern Eurasia. Their mutual relationships relied on the military and dynastic alliances, tributes and religious proselytism, occasionally interrupted by military raids. Major power in the region was Novgorod Republic that encompassed Pskov, Karelia and Izhora that conducted trade i.a. via Estonian lands seeing them as tributaries.[2] Novgorodians established a castle and settlement as far westwards as Yuriev (Tartu) but were unable to maintain its presence in Estonia during the invasion from the West.[3] The present-day borderline between Russia and Estonia may be traced back to the XIII century when the Livonian Crusade halted on the border with Pskovian lands East of Pskovo-Chudskoye or Peipus lake basin, river Narva and minor rivers to the South from the lake. Further campaigns of either sides has not brought any sustainable gains so Denmark, Sweden and Livonian Confederation on the Western side, and Novgorod, Pskov and later Muscovy on the East established fortresses in the strategic points of the borderland which they were able to support.[4][5] Examples are Vastselinna and Narva on Estonian side, Ivangorod, Yamburg and Izborsk on the Russian side. Peace treaties mostly confirmed the basic borderline along the Narva river and the lake,[6] such as Treaty of Teusina (1595) that left Narva township with Sweden. Despite the extensive cross-border trade and mixed populations of the borderlands, the law, language, religion of Russian principalities went a different way compared to their Western neighbors.[7][8] Livonia and Sweden used the border as means of containment of the rising Tsardom, preventing craftsmen and arms supplies from Western Europe from entering Russia.[9]

Administrative border in Sweden and Russia

During the early XVI century turmoil in Russia, Kingdom of Sweden conquered the whole Novgorodian coastline of the Eastern Baltics and formed Swedish Ingria. Its border with Swedish Estonia went along Narva river leaving Narva township with Ingria.[10] Russian-Livonian border South from the lake was restored. After the Great Northern War Russia regained the lost possessions on the Baltics and built its new capital there, Saint-Petersburg, as well as conquered Swedish Estonia soon turned into an imperial governorate. However, during the two centuries of the Russian rule the Eastern borders of Estonian and Livonian governorates remained mostly intact, as did their semi-autonomous administrative and cultural framework. A notable change was the status of Narva town, briefly excluded from St.Petersburg Governorate during the rule of Paul I. Like Sweden, Russia did not manage to harmonize its possessions East and West of the borderline formed in the late Middle Ages, although migration process went on during two centuries under the Russian Empire: Russian 'old believers' resettled to Eastern Estonia and poor Estonian peasants - to the Western parts of Pskov and St.Petersburg governorates.[11][12][7][13]

Establishing of Russian-Estonian border and the interwar period

After the February Revolution in 1917 the Provisional government of Russia carried out an administrative reform that created the Autonomous Governorate of Estonia where the former Governorate of Estonia and the Estonian-speaking areas of the Governorate of Livonia were merged.[14][15][16] On February 24, 1918 its National Council, the Maapäev, declared the independence of Estonia. It listed the Estonian regions to form the Republic and mentioned that “Final determination of the boundaries of the Republic in the areas bordering on Latvia and Russia will be carried out by plebiscite after the conclusion of the present World War”[17]. Such plebiscite was carried out only in Narva township on 10 December 1917, where the majority voted for Estonian administration.[18] Russian Bolshevik government accepted its results and by decree of 21 December town of Narva was transferred from Russian Republic to the Autonomous Governorate of Estonia.[19]

According to the Peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk of 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and Germany that controlled all the Estonia by that time, Russia relinquished its rights on Estonia, and the border between the Grand Duchy of Livonia and Russia should have followed the Narva river.[20] In late 1918 a war broke out between Soviet Russia and Estonia supported by the White Russian Northwestern Army and the British Navy. By February 1919 Estonians repelled the Red Army back to Russia and in April 1919 the Bolshevik government initiated the peace talks with Estonia.[21] The British government, however, pressed to continue the war and in May and October 1919 Estonian and White Russian troops attempted two major offensives towards Petrograd. As both of them failed, the peace talks continued and the borderline question was brought up on the 8 December 1919. The Estonian party proposed Russian counterpart to cede about 10000 sq.km. from the Petrograd and Pskov Governorates to the East of the pre-war borders. The next day Russians reacted likewise offering Estonia to cede its Northeastern part. During December 1919 the borderline was agreed to go along the actual frontline between the belligerents.

As per the Tartu Peace Treaty of 02 February 1920 Estonia gained from Russia a narrow land strip East of Narova river including Ivangorod as well as Pechorsky uyezed with Pechory town and lands Southwest from the Pskovskoye (Est. – Phikva) lake including Pskovian town of Izborsk known since year 862 A.D. The Pechory (Est.- Petseri) County was inhabited predominantly by Russians and Seto, and unlike other regions of Estonia proper its municipal self-governance was subject to veto power by a special officer appointed from Tallinn.[22]

Russia and Estonia agreed to demilitarize the near borderland and the whole lake basin leaving armed only the required border guard. The border trespassing by the local population that appeared split between two states was a common issue, rising concerns of smuggling and spying on both sides. Soviet illegal immigrants who were ethnic Estonians were offered refugee status in Estonia to avoid their expulsion back to the USSR.[23]

Wartime and Soviet period

In 1940 Estonia was annexed by the USSR converting the former national border into administrative demarcation line of Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic and Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic of the USSR. According to the Internal Affairs People’s Commissariat decree №867 of 06/12/1940 the Barrage Zone was created along the former borderline to prevent “…intrusion of spies, terrorists and anti-revolutionary elements” into the USSR mainland.[24] Border guards were assigned to allow restricted passage through the borderline only of the persons owning the required permission.

During the Nazi invasion of 1941–1944 the Estonian Republic was turned into Generalbezirk Estland of the Reichskommissariat Ostland. The Russian-Estonian borderline acted as its eastern border with the Nazi military administration area of Leningrad oblast, where ‘racially-clean’ Reichsgau Ingermanland was projected. The latter included Narva town with its vicinity, that was excluded from the Generalbezirk Estland. According to the alternative Nazi Lebensraum designs, instead of establishing a Reichsgau the territory of Estland, renamed to Peipusland, was supposed to be vastly extended eastwards to Volkhov river to allow for Estonians to be resettled there, and Germans to take their place in Estonia.[25]

In 1944 the Nazis were driven out of most of the Eastern Baltics. With a decree of the Soviet parliament of 23 August 1944 major share of the borderland areas earlier ceded to Estonia in 1920 (including Pechory, Izborsk and lands to the East of Narova river) was transferred from Estonian SSR to Russian SFSR. Other Estonian gains of 1920, including Pogranichniy a.k.a. Piirisaar island on the lake were left with Estonia. Township of Narva being on the both parts of the river was split into Western (Narva) and Eastern (Ivangorod) parts, thus replicating the border as it existed in the XVI century.[26]

In 1957 the Soviet parliament authorized a small exchange of territories between two Soviet Republics in the border area South of the lakes, forming the Russian semi-exclave Dubki and famous Estonian Saatse boot.[27] By that time the borders of the Soviet republics became fully transparent and no border control was enforced. Schools for Russian- and Estonian-speaking populations existed on the both sides of the administrative border. Estonian and Russian borderland areas were connected by extensive bus, rail and ferry services.

Transitional period and current state

In 1991 the USSR was dissolved, Estonia restored its independence. The administrative boundary became de-facto national border of Russia and Estonia that required formal recognition, delimitation and establishing of crossing points. During early 1990-ties there were attempts to torment a pro-Estonian sentiment in the Russian borderland, where billboards invited local delegates to the Citizen’s Congress of Estonia and simulated border landmarks placed along 1920 border.[28][29] For Russians living in Pechory district the Estonian immigration authorities offered Estonian citizenship on much more concessionary terms than to most Russians in Estonia. Russia reciprocated with easier naturalization rules for the resident non-citizens living in Estonia.[30] In 1993 a pro-autonomy plebiscite was conducted in Narva, but Estonian court invalidated its results.[31]

In 1994 the actual border, dubbed ‘line of control’, was demarcated by the Russian authorities.[32] The border treaty talks have commenced, headed by Vassiliy Svirin and Ludvig Chizhov from the Russian side, and Raul Malk and Jüri Luik from Estonian side. Apart from Russian non-acceptance of Estonian references to 1920 border, the talks were complicated by the different sets of coordinates used by the parties. By 1995 the existing border going mostly along the Soviet administrative boundary was agreed. An exception was the border on the lake going closer to 1920 border, and minor territorial exchanges of 128,6 Ha on the land and 11,4 sq.km on the lake.[33] Inter alia, the notorious Saatse boot was supposed to be exchanged for Marinova and Suursoo landplots in the areas near Meremae and Varska. In 1999 the terms of the Border agreement were finalized and in 2005 it was signed by both parties. However, during the ratification the Estonian side added a preamble referring to the 1920 Treaty making a case for possible territorial dispute, so Russian side refused to ratify it and the agreement was terminated.[34][2][35][36]

In 2014 Foreign ministers of Estonia and Russia signed the new Border Agreement without the disputed preamble.[37][38] Also the treaty of the sea border across Narva bay and Gulf of Finland was agreed. Both agreements were submitted to the parliamentary ratification in Estonia and Russia, however, with little progress because of political reasons.[39] In 2017 Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov commented that Russia will consider ratification once the bilateral relations constructively improve. In 2017-2018 Conservative People’s Party of Estonia (EKRE) proposed to terminate the 2014 Border agreement referring to the events in the Ukraine.[40] In 2019 speaker of Estonian parliament claimed that the agreement may be ratified only if the borderline follows the terms of 1920 Treaty.[41] As of August 2020, the treaty has not been ratified in either of the countries.[42]

Equipment

As the border is the Eastern border of EU and NATO, both sides are heavily investing in the proper equipment of the border with means of trespassing control. After the 2014 incident with Estonian security police Eston Kohver’s detention the Estonian side demarcated the border aiming to «prevent unintended illegal border crossings». By 2020 whole Estonian side of the border was planned to be equipped with surveillance facilities, a 110-km long fence and a road for policemen’s ATVs, the estimated cost reached 179 million euros.[43] By 2017 over five hundred poles were established along the land borderline, and 175 spar buoys on the lakes. Estonian side has also upgraded its main crossing points in Narva and Luhamaa.

Transit

Russia has established Border security zone regime along its Western borders. The 5-kilometre area adjacent to the border may be visited by the non-local population if a permit is obtained, for tourist, business or private reasons.[44] Internal checkpoints exist on the roads. Russian fishermen on the Chudskoye lake and Narova river are required to give a notice each time they plan to sail and to return to harbour before the sunset. Transit to the border crossing points requires no such permits. Until the border agreement is ratified, Saatse boot remains with Russia; it may be freely crossed from and to Estonia en route from Värska to Ulitina with no checks provided that no stops are made in transit.[1]

To address the issue of huge border queues of passenger cars and lorries, since 2011 the Estonian side requires the outbound travellers to reserve their time at the border checkpoint, electronically or by phone.[45] Russians planned to set up the similar system, but it didn’t go beyond the test.

Early 1990-ties there was a stable arms smuggling channel from Estonia to Russia through the barely controlled border, causing severe incidents.[46] The volumes of Russian-European transit via Estonia, once essential for the Russian exporters, has been declining since 2007, partly because of political tensions, partly because of construction of Ust-Luga sea port.[47]

Border crossings

Crossing the border is allowed only at border controls. Most people need a visa on one or both sides of the border. Listed from North:[48]

- Narva-Ivangorod on road E20 / 1 / M11 between Narva and Ivangorod (for automobiles and pedestrians of any nations)

- Narva-Ivangorod on Tallinn-Narva-St. Petersburg railway, at Narva and Ivangorod (for railway passengers)

- Narva 2-Parusinka on a local road in Narva (only for citizens or residents of Estonia and Russia)

- Saatse-Krupp, on road 106 at Saatse (only for citizens or residents of Estonia and Russia)

- Koidula-Pechory on Valga-Pechory railway, at Koidula (as of 2020 freight service only)

- Koidula-Kunichina Gora on road 63 at Koidula, near Pechory town (for automobiles and pedestrians of any nations)

- Luhamaa-Shumilkino on road E77 / 7 / A212 between Riga and Pskov, near Luhamaa village (for automobiles and pedestrians of any nations)

One more checkpoint that existed in 1990-ties near Pechory and checkpoints on the lake harbours are now closed.

See also

References

- "Estonia, Russia to exchange 128.6 hectares of land under border treaty". Postimees. 2013-05-28. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- Zayats D., Manakov A. Will there be new Russian-Estonian border? (Быть ли новой российско-эстонской границе?) // Pskov Regionological Journal (Псковский регионологический журнал). — 2005. — № 1. — pp. 136–145. (in Russian) https://istina.msu.ru/publications/article/10269535/

- Miljan, Toivo (2004-01-13). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6571-6.

- "ETIS - Anzeige: Anti Selart: Narva jõgi - Virumaa idapiir keskajal, in: Akadeemia 1996, S. 2539-2556". www.etis.ee. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- Selart, Anti (1996). "Narva jõgi - Virumaa idapiir keskajal". Akadeemia (in Estonian). 8 (12).

- Napjerski K.E., Russian-Livland Treaties (Русско-ливонские акты - Russisch-Livlaendische Urkunden) — Saint-Petersburg: Issue of the Archeographic Commission, 1868. (in Russian)

- Manakov A., Yevdokimov S., Sustainability of the border in Pskov region: a historical and geographical analysis (Устойчивость границ Псковского региона: историкогеографический анализ) // Pskov Regionological Journal (Псковский регионологический журнал). № 10. — Pskov State University, 2010. — pp. 29-48. (in Russian) https://istina.msu.ru/publications/article/98899527/

- Selart A. Eesti idapiir keskajal. Tartu, 1998

- Maasing, Madis (2010). "ETIS - "РУССКАЯ ОПАСНОСТЬ" В ПИСЬМАХ РИЖСКОГО АРХИЕПИСКОПА ВИЛЬГЕЛЬМА ЗА 1530–1550 гг (in Russian)" [The «Russian threat» in the letters of Riga’s archbishop Wilhelm in 1530–1550]. www.etis.ee. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- Shmelev, Kirill Vladimirovich (2017). ""Чертеж Русским и Шведским городам" как источник о фортификации пограничных крепостей в период войны 1656 г. История и археология"" ["Drawing of the Russian and Swedish towns" as the source of knowledge about borderland castles during the war of 1656 (in Russian)] (PDF). "Война и оружие. Новые исследования и материалы". Труды восьмой международной научно-практической конференции. Т IV: 561–573.

- Raun, Toivo U. (1986). "Estonian Emigration within the Russian Empire, 1860-1917". Journal of Baltic Studies. 17 (4): 350–363. doi:10.1080/01629778600000211. ISSN 0162-9778. JSTOR 43211398.

- Weimarn F. (1864). Матеріалы для географіи и статистики Россіи, собранные офицерами Генеральнаго штаба. Лифляндская губернія [Statistical and Geographical Data of Russia Collected by the Officers of the Army Headquarters. Volume: Livland Governorate.]. Saint-Petersburg.

- Манаков А. Г. Динамика численности и этнического состава населения Северо-Запада России в xviii-xix вв // Псковский регионологический журнал. — 2016. — № 1 (25). — С. 59–81.

- Бахтурина, Александра Юрьевна. "На пути к эстонской государственности. Временное правительство и административные преобразования в Эстляндской губернии» в 1917 году: историографические и источниковедческие аспекты". elib.pstu.ru. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- О временном« устройстве административного управления и местного самоуправления Эстляндской губернии» от 30 марта 1917 г. // Собрание узаконений и распоряжений правительства, издаваемое при Правительствующем сенате. Отдел I. – 28 июля 1917. – № 173. – Ст.

- Bakhturina A.Y. Changes in the administrative boundaries of the Baltic provinces in spring–summer, 1917 RSUH/RGGU Bulletin Series "Political Science. History. International Relations". 2017;(4/2):177-185. (In Russ.) https://politicalscience.rsuh.ru/jour/article/view/163?locale=ru_RU

- "Declaration of Independence | President". www.president.ee. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- "Eestlaste asuala ühendatakse üheks kubermanguks | Histrodamus.ee". histrodamus.ee. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- Buttar, Prit (19 September 2017). The splintered empires : the Eastern Front 1917-21. Oxford, UK. ISBN 978-1-4728-1985-7. OCLC 1005199565.

- Lincoln, W. B. (1986). Passage through Armageddon : The Russians in War & Revolution 1914–1918. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 489–491. ISBN 0-671-55709-2.

- Buttar, Prit (19 September 2017). The splintered empires : the Eastern Front 1917-21. Oxford, UK. ISBN 978-1-4728-1985-7. OCLC 1005199565.

- Alenius, Kari, “Petserimaa ja Narvataguse integreerimine Eestiga ning idaalade maine Eesti avalikkuses 1920–1925”, Akadeemia, 11 (1999), 2301–2322.

- Alenius, Kari, “Dealing with the Russian Population in Estonia, 1919–1921”, Ajalooline Ajakiri, 1/2 (2012), 167–182

- "Часть 4 - Том 1- Книга вторая (1.01 — 21.06.1941 г.) - Статьи и публикации - Мозохин Олег Борисович - из истории ВЧК ОГПУ НКВД МГБ". mozohin.ru. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- SEPPO MYLLYNIEMI.

- Manakov A. G., Mikhaylova A. A. Changes in the territorial and administrative division of northwest russia over the soviet period // International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues. — 2015. — Vol. 5. — P. 37–40. https://istina.msu.ru/publications/article/98695617/

- Границы России в XVII—XX веках / Н. А. Дьякова, М. А. Чепелкин. — М. : Центр воен.-стратег. и воен.-технол. исслед. Ин-та США и Канады, 1995. — 236 с. :

- Б.Костомаров. К чему это приведёт? О попытках изменения границ между РСФСР и Эстонией // Псковская правда. — 1990. — 1 сентябрь.

- "Borders and Demarcation Lines Between Estonia and Russia". ICDS. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- Manakov, Andrei & Kliimask, Jaak. (2020). Russian-Estonian border in the context of post-soviet ethnic transformations. GEOGRAPHY, ENVIRONMENT, SUSTAINABILITY. 13. 16-20. 10.24057/2071-9388-2019-68.

- "Estonian Court Invalidates Narva Referendum". AP NEWS. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- Manakov, Andrei G.; Kliimask, Jaak (2020-03-31). "Russian-Estonian border in the context of post-soviet ethnic transformations". GEOGRAPHY, ENVIRONMENT, SUSTAINABILITY. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- "The Story of the Negotiations on the Estonian-Russian Border Treaty". ICDS. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- Россия отозвала подписи под договорами о границе с Эстонией

- Levinsson, Claes (2006). "The Long Shadow of History: Post-Soviet Border Disputes—The Case of Estonia, Latvia, and Russia". Connections. 5 (2): 98–110. doi:10.11610/Connections.05.2.04. ISSN 1812-1098. JSTOR 26323241.

- Alatalu, Toomas (2013-10-01). "Geopolitics Taking the Signature from the Russian-Estonian Border Treaty (2005)". TalTech Journal of European Studies. 3 (2): 96–119. doi:10.2478/bjes-2013-0015. S2CID 154094569.

- "Russia Finally Signs Border Treaty With Estonia". Associated Press. 18 February 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- Reuters Staff (2014-02-18). "After 20 years, Russia and Estonia sign border treaty". Reuters. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- ERR, BNS, ERR News | (2020-01-02). "Russian politician condemns New Year's greeting border comments by Põlluaas". ERR. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- ERR (2015-12-10). "EKRE pushing for Treaty of Tartu mention in border treaty". ERR. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- ERR, ERR, ERR News | (2019-05-10). "Prime minister: We have to be realistic about border ratification". ERR. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- "Парламент Эстонии назвал личным мнением слова спикера о границе с Россией". РБК. Retrieved 2020-01-14.

- Estonia to build fence along Russian border (Yahoo News, 27 August 2015)

- "Приказ ФСБ России от 19 июня 2018 г. № 283 "О внесении изменений в Правила пограничного режима, утвержденные приказом ФСБ России от 7 августа 2017 г. № 454" (не вступил в силу)". www.garant.ru. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- "GoSwift, a Queue Management Service | European Data Portal". www.europeandataportal.eu. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- ""Nieder mit der Grenze" - DER SPIEGEL 52/1992". www.spiegel.de. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- ERR (2016-10-27). "Rail freight transport between Estonia, Russia remains on decline". ERR. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- Official Journal of the European Union, document 2014/C 420/09