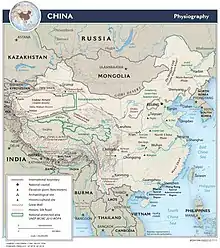

China–Russia border

The Chinese–Russian border or the Sino-Russian border is the international border between China and Russia. After the final demarcation carried out in the early 2000s, it measures 4,209.3 kilometres (2,615.5 mi),[1] and is the world's sixth-longest international border.

The China–Russian border consists of two non-contiguous sections separated: the long eastern section between Mongolia and North Korea and the much shorter western section between Kazakhstan and Mongolia.

Description

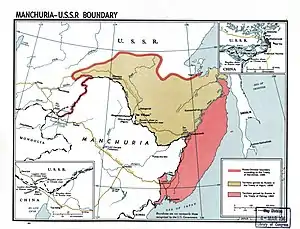

The eastern border section is over 4,000 kilometres (2,500 mi) in length. According to a joint estimate published in 1999, it measured at 4,195 kilometres (2,607 mi).[2] It starts at the eastern China–Mongolia–Russia tripoint (49°50′42.3″N 116°42′46.8″E), marked by the border monument called Tarbagan-Dakh (Ta'erbagan Dahu, Tarvagan Dakh).[3][4] From the tripoint, the border line runs north-east, until it reaches the Argun River. The border follows the Argun and Amur river to the confluence of the latter with the Ussuri River. It divides the Bolshoy Ussuriysky Island at the confluence of the two rivers, and then runs south along the Ussuri. The border crosses Lake Khanka, and finally runs to the south-west. The China–Russia border ends when it reaches the Tumen River, which is the northern border of North Korea. The end point of the China–Russia border, and the China–North Korea–Russia tripoint, at (42°25′N 130°36′E), is located only a few kilometers before the river flows into the Pacific Ocean, the other end of the North Korea–Russia border.

The much shorter (less than 100 kilometres (62 mi)) western border section is between Russia's Altai Republic and China's Xinjiang. It runs in the mostly snow-covered high elevation area of the Altai Mountains. Its western end point is the China–Kazakhstan–Russia tripoint, whose location is defined by the trilateral agreement as 49°06′54″N 87°17′12″E, elevation, 3327 m.[5] Its eastern end is the western China–Mongolia–Russia tripoint, at the top of the peak Tavan Bogd Uul (Mt Kuitun),[6][7] at the coordinates 49°10′13.5″N 87°48′56.3″E.[4][7][8]

History

The Tsarist era (pre-1917)

Today's Sino-Russian border line is mostly inherited by Russia (with minor adjustments) from the Soviet Union, while the Sino-Soviet border line was essentially the same as the border between the Russian and Qing Empires, settled by a number of treaties from the 17th through to the 19th centuries. Border issues first became an issue following Russia's rapid expansion into Siberia in the 17th century, with intermittent skirmishes occurring between them and Qing China.[9] Below is a list of important border treaties, along with the indication as to which section of today's Sino-Russian border were largely set by them:

- Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) - this covered the far eastern section of the border, creating a line along the Argun River and Shilka River, then proceeding overland via the Stanovoy Mountains, and then along the Uda river, terminating at the Tugur peninsula by the Sea of Okhotsk.[9]

- Treaty of Kyakhta (1727), plus supplementary protocols of the same year - these were concerned mostly with the border line that is currently the Mongolia–Russia border (Mongolia then being part of China), this fixing a line from the river Irtysh in the west to the Argun in the east.[9]

- Treaty of Aigun (1858) - this shifted the eastern border to run along the Amur River out to the Okhotsk.[9]

- Convention of Peking (1860) - this finalised the eastern stretch of the border, with China ceding to Russia the territory of modern Primorsky Krai and southern Khabarovsk Krai.[9]

- Treaty of Tarbagatai (1864) - this created the western section of the border in Central Asia, with the bulk of this border now forming China's borders with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (with modifications).[10] The border was modified via later treaties such as the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881), though the modern Russian section remained at the same place.[9]

- Qiqihar Agreement (1911) - modified the eastern border along the Argun slightly, however China later repudiated the treaty.[9]

The Sino-Soviet border (1917–1991)

.png.webp)

Following the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the later formation of the Soviet Union, there have been a number of issues along the border:

- In 1911 Outer Mongolia declared independence from China; the USSR recognised the country the 1921, thus removing a large part of the China-USSR border and splitting it into two sections.[9] China later recognised Mongolian independence in 1946.[9]

- Sino-Soviet conflict (1929) - a conflict largely centred on the Chinese Eastern Railway.

- Sino-Soviet border conflict (1969) - this was a serious seven-month undeclared military conflict between the Soviet Union and China at the height of the Sino-Soviet split in 1969 (China having being taken over by Communists in 1949). Although military clashes ceased that year, the underlying issues were not resolved until the 1991 Sino-Soviet Border Agreement. The most serious of these border clashes, which brought the two countries to the brink of all-out war, occurred in March 1969 in the vicinity of Zhenbao (Damansky) Island on the Ussuri (Wusuli) River; as such, Chinese historians most commonly refer to the conflict as the Zhenbao Island Incident.[11] Heavily militarised following the war, the border slowly opened after 1982, allowing the first exchange of goods between the two countries, though the territorial disputes remained unresolved. Between 1988 and 1992 the cross-border commerce between Russia and the Heilongjiang province increased threefold, with the number of legal Chinese workers in Russia increasing from 1,286 to 18,905.[2]

Post-1991

The waning years of the Soviet Union saw a reduction of the tensions on the then heavily fortified Sino-Soviet border. In 1990–91, the two countries agreed to significantly reduce their military forces stationed along the border.[12] To this day one can find numerous abandoned military facilities in Russia's border districts.[13]

Even though the Sino-Soviet border trade resumed as early as 1983–85, it accelerated in 1990–91; the rate of cross-border trade continue increasing as the USSR's former republics became separate states. To accommodate increasing volume of travel and private trade, a number of border crossings were re-opened.[12] In early 1992, China announced border trade incentives and the creation of special economic zones (SEZs) along the Sino-Russian border, the largest of these being in Hunchun, Jilin.[12]

In 1991, China and USSR signed the 1991 Sino-Soviet Border Agreement, which intended to start the process of resolving the border disputes held in abeyance since the 1960s. However, just a few months later the USSR was dissolved, and four former Soviet republics — Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan — inherited various sections of the former Sino–Soviet border.

It took more than a decade for Russia and China to fully resolve the border issues and to demarcate the border. On May 29, 1994, during Russian Prime Minister Chernomyrdin's visit to Beijing, an "Agreement on the Sino-Russian Border Management System intended to facilitate border trade and hinder criminal activity" was signed. On September 3, a demarcation agreement was signed for the short (55 kilometres (34 mi)) western section of the binational border; the demarcation of this section was completed in 1998.[14]

In November 1997, at a meeting in Beijing, Russian President Boris Yeltsin and General Secretary and Chinese President Jiang Zemin signed an agreement for the demarcation of the much longer (over 4,000 kilometres (2,500 mi)) eastern section of the border, in accordance with the provisions of the 1991 Sino-Soviet agreement.

The last unresolved territorial issue between the two countries was settled by the 2004 Complementary Agreement between the People's Republic of China and the Russian Federation on the Eastern Section of the China–Russia Boundary.[15] Pursuant to that agreement, Russia transferred to China a part of Abagaitu Islet, the entire Yinlong (Tarabarov) Island, about half of Bolshoy Ussuriysky Island, and some adjacent river islets. The transfer has been ratified by both the Chinese National People's Congress and the Russian State Duma in 2005, thus ending the decades-long border dispute. The official transfer ceremony was held on-site October 14, 2008.

Border management

As with many other international borders, a bilateral treaty exists concerning the physical modalities of managing the China–Russia border. The currently valid agreement was signed in Beijing in 2006.[16]

The treaty requires the two states to clear trees in a 15 metres (49 ft)-wide strip along the border (i.e. within 7.5 metres (25 ft) from the border line on each side of it) (Article 6).[16]

Civil navigation is allowed on the border rivers and lakes, provided the vessels of each country stay on the appropriate side of the dividing line (Article 9); similar rules apply to fishing in these waters (Article 10). Each country's authorities will carry out appropriate measures to prevent grazing livestock from crossing into the other country, and will endeavor to apprehend and return any livestock that wanders onto their territory from across the border (Article 17). Hunting using firearms is prohibited within 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) from the border line; hunters are prohibited from crossing the border in pursuit of a wounded animal (Article 19).[16]

Detained illegal border crossers are supposed to be normally returned to their country of origin within 7 days from their apprehension (Article 34).[16]

Border crossings

Eastern section

According to the Russia's border agency, as of October 1, 2013, there are 26 border crossings on the China–Russia border; all of them are located on the eastern section of the border. Twenty-five of them are provided for by the bilateral agreement of January 27, 1994, and one more is designated by an additional special order of the Russian government. The 25 crossing points established by the treaty include four railway crossings (at one of them, at Tongjiang/Nizhneleninskoye, the railway bridge is still under construction), eleven as highway crossings, one as river crossing, and nine as "mixed" (mostly ferry crossings).[1][17]

At present three railway lines cross the border. The two railway border crossings at Zabaikalsk/Manzhouli and Suifenhe/Grodekovo are over a century old, brought into existence by the original design of Russia's Transsiberian Railway that took a shortcut across Manchuria (the Chinese Eastern Railway). The third railway crossing, near Hunchun/Makhalino, operated between 2000 and 2004, was then closed for a few years,[18][19] and only recently reopened. Construction has started on a Tongjiang-Nizhneleninskoye railway bridge near Tongjiang/Nizhneleninskoye, which will become the fourth railway border crossing.

Western section

As of 2018, there were no border crossings of any kind on the two countries' short and remote western border section.[20]

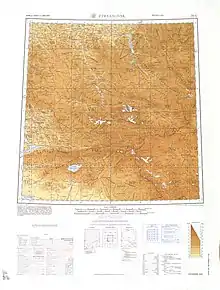

According to Russian topographic maps, the lowest mountain passes on the western section of the border are the Betsu-Kanas Pass (перевал Бетсу-Канас), elevation 2,671.3 metres (8,764 ft)[8][21] and Kanas (перевал Канас), elevation 2,650 metres (8,690 ft).[22] No roads suitable for wheeled vehicles exist over these two passes, although a difficult dirt road approaches from the Russian side to within 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from the Kanas Pass. Until the Soviet authorities closed the border in 1936, Kazakh nomads would occasionally use these passes.[21]

Proposals exist for the construction of a cross-border highway and the Altai gas pipeline from China to Russia, which would cross the western section of the Sino-Russian border.[23]

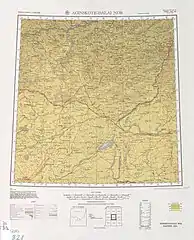

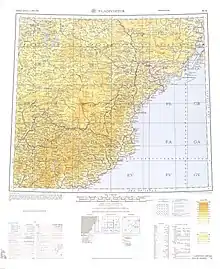

Historical maps

Historical maps of the border from west to east in the International Map of the World, mid-20th century:

western section

western section

References

- Китай Archived 2015-07-07 at the Wayback Machine (China), at the Rosgranitsa site

- Sébastien Colin, Le développement des relations frontalières entre la Chine et la Russie, études du CERI n°96, July 2003. (Note: this publication preceded the 2004 final settlement, and thus the estimate may slightly differ from the current number).

- ПРОТОКОЛ-ОПИСАНИЕ ТОЧКИ ВОСТОЧНОГО СТЫКА ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫХ ГРАНИЦ ТРЕХ ГОСУДАРСТВ МЕЖДУ ПРАВИТЕЛЬСТВОМ Российской Федерации, ПРАВИТЕЛЬСТВОМ МОНГОЛИИ и ПРАВИТЕЛЬСТВОМ КИТАЙСКОЙ НАРОДНОЙ РЕСПУБЛИКИ Archived 2018-02-15 at the Wayback Machine (Protocol between the Government of the Russian Federation, the Government of Mongolia, and the Government of the People's Republic of China, describing the eastern junction point of the borders of the trees states) (in Russian)

- Соглашением между Правительством Российской Федерации, Правительством Китайской Народной Республики и Правительством Монголии об определении точек стыков государственных границ трех государств (Заключено в г. Улан-Баторе 27 января 1994 года) Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine (The Agreement between the Government of the Russian Federation, the Government of the People's Republic of China, and the Government of Mongolia on the determination of the points of junction of the national borders of the three states) (in Russian)

- Соглашение между Российской Федерацией, Республикой Казахстан и Китайской Народной Республикой об определении точки стыка государственных границ трех государств, от 5 мая 1999 года (The agreement between the Russian Federation, Republic of Kazakhstan, and the People's Republic of China on determining the junction point of the international borders of the three states. May 5, 1999)

- 中华人民共和国和俄罗斯联邦关于中俄国界西段的协定 (Agreement between the PRC and RF in regard to the western section of the China-Russia border), 1994-09-03 (in Chinese)

- ПРОТОКОЛ-ОПИСАНИЕ ТОЧКИ ЗАПАДНОГО СТЫКА ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫХ ГРАНИЦ ТРЕХ ГОСУДАРСТВ МЕЖДУ ПРАВИТЕЛЬСТВОМ Российской Федерации, ПРАВИТЕЛЬСТВОМ МОНГОЛИИ и ПРАВИТЕЛЬСТВОМ КИТАЙСКОЙ НАРОДНОЙ РЕСПУБЛИКИ (ПОДПИСАН в г. ПЕКИНЕ 24.06.1996) Archived 2018-02-16 at the Wayback Machine (Protocol between the Government of the Russian Federation, the Government of Mongolia, and the Government of the People's Republic of China, describing the western junction point of the borders of the three states. Signed in Beijing, June 24, 1996) (in Russian)

- Soviet Topo map M45-104, scale 1:100,000, (in Russian)

- "International Boundary Study No. 64 (revised) - China-USSR Boundary" (PDF). US Department of State. 13 February 1978. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- "НАЧАЛО РУССКО-КИТАЙСКОГО РАЗГРАНИЧЕНИЯ В ЦЕНТРАЛЬНОЙ АЗИИ. ЧУГУЧАКСКИЙ ПРОТОКОЛ 1864 г." Archived from the original on 2012-12-26. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- People.com.cn. "People.com.cn." 1969年珍宝岛自卫反击战. Retrieved on 5 November 2009.

- Davies, Ian (2000), REGIONAL CO-OPERATION IN NORTHEAST ASIA. THE TUMEN RIVER AREA DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM, 1990–2000: IN SEARCH OF A MODEL FOR REGIONAL ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION IN NORTHEAST ASIA (PDF), North Pacific Policy Papers #4, p. 6, archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-15, retrieved 2015-07-14

- Numerous photo reports from such sites exist on the internet. See e.g. Заброшенный укрепрайон на Большом Уссурийском острове (Abandoned fortified area in Bolshoy Ussuriysky Island)

- Chen, Qimao, "Sino-Russian relations after the break-up of the Soviet Union", in Chufrin, Gennady (ed.), Russia and Asia: the Emerging Security Agenda (PDF), pp. 288–291, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-19, retrieved 2015-07-15

- Дополнительное соглашение между Российской Федерацией и Китайской Народной Республикой о российско-китайской государственной границе на of the low-lying Russian river bank.citation needed]ее Восточной части Archived 2011-08-12 at the Wayback Machine. October 14, 2004 (in Russian)

- Соглашение между Правительством Российской Федерации и Правительством Китайской Народной Республики о режиме российско-китайской государственной границы Archived 2015-07-09 at the Wayback Machine (Agreement between the Government of the Russian Federation and the Government of the People's Republic of China on the management of the Russia-China international border)

- The 1994 agreement is: Соглашение между Правительством Российской Федерации и Правительством Китайской Народной Республики о пунктах пропуска на российско-китайской государственной границе. Пекин, 27 января 1994 года Archived 2015-07-21 at the Wayback Machine (The Agreement between the Government of the Russian Federation and the Government of the People's Republic of China on the border crossing points on the Russia–China international border. Beijing, January 27, 1994). The text only lists 21 border crossing points.

- Переход Махалино–Хуньчунь (Makhalino-Hunchun border crossing), 2011-08-12 (in Russian)

- Россия и Китай реанимируют бездействующий погранпереход (Russia and China will revive a defunct border crossing), 20.09.2012 (in Russian)

- See e.g. the apparently exhaustive list of China's border crossing in Xinjiang (新疆边贸口岸信息汇总, 2009-05-07), which includes no crossings on the border with Russia. The list of Russia's border crossings at rosgranitsa.ru does not include any crossings in that area either.

- Перевал Бетсу-Канас (Betsu-Kanas Pass) (in Russian)

- Перевал Канас (Kanas Pass) (in Russian)

- Перевал "Канас" станет пунктом сдачи газа РФ китайским партерам по "западному маршруту" (Gas will be transferred to the Chinese partners over the Kanas Pass along the Western Route [of the pipeline]), 2015-05-08

Further reading

- Burr, William. "Sino-American relations, 1969: the Sino-Soviet border war and steps towards rapprochement." Cold War History 1.3 (2001): 73-112.

- Gerson, Michael S. The Sino-Soviet Border Conflict: Deterrence, Escalation, and the Threat of Nuclear War in 1969 (2010) online

- Humphrey, Caroline. "Loyalty and disloyalty as relational forms in Russia’s border war with China in the 1960s." History and Anthropology 28.4 (2017): 497–514. online

- Kuisong, Yang. "The Sino-Soviet Border Clash of 1969: From Zhenbao Island to Sino-American Rapprochement." Cold War History 1.1 (2000): 21–52.

- Robinson, Thomas W. "The Sino-Soviet border dispute: Background, development, and the March 1969 clashes." American Political Science Review 66.4 (1972): 1175–1202. online

- Urbansky, Sören:

- Beyond the Steppe Frontier: A History of the Sino-Russian Border (2020) a comprehensive history; excerpt

- "A Very Orderly Friendship: The Sino-Soviet Border under the Alliance Regime, 1950-1960." Eurasia Border Review 3.Special Issue (2012): 33-52 online.

- "The Unfathomable Foe. Constructing the Enemy in the Sino-Soviet Borderlands, ca. 1969–1982." Journal of Modern European History10.2 (2012): 255–279. online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to China-Russia border. |

- The lost frontier: Treaty maps that changed Qing's northwestern boundaries

- The list of Russia's border crossing on the border with China (on the official site of Russia's Border Agency) (in Russian)

- The Sino-Soviet Border Conflict; Deterrence, Escalation, and the Threat of Nuclear War in 1969 Michael S. Gerson CNA.org November 2010

- International Boundary Study No. 64 (Revised) – February 13, 1978 China – U.S.S.R. Boundary