Filozoa

The Filozoa are a monophyletic grouping within the Opisthokonta. They include animals and their nearest unicellular relatives (those organisms which are more closely related to animals than to fungi or Mesomycetozoa).[1]

| Filozoans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orange elephant ear sponge, Agelas clathrodes, in foreground. Two corals in the background: a sea fan, Iciligorgia schrammi, and a sea rod, Plexaurella nutans. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | Unikonta |

| (unranked): | Obazoa |

| (unranked): | Opisthokonta |

| (unranked): | Holozoa |

| (unranked): | Filozoa Shalchian-Tabrizi et al., 2008 |

| Subgroups | |

Three groups are currently assigned to the clade Filozoa:

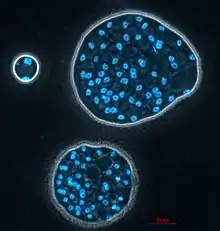

- Group Filasterea - recently erected to house the genera Ministeria and Capsaspora

- Group Choanoflagellatea - collared flagellates

- Kingdom Animalia - the animals proper

Etymology

From Latin filum meaning "thread" and Greek zōion meaning "animal".

Phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree is[2][3][4] The holomycota tree is following Tedersoo et al.[5]

| Opisthokonta |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1300 mya |

Characteristics

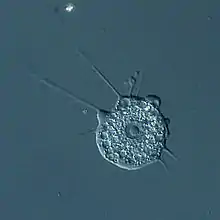

The ancestral opisthokont cell is assumed to have possessed slender filose (thread-like) projections or 'tentacles'. In some opisthokonts (Mesomycetozoa and Corallochytrium) these were lost. They are retained in Filozoa, where they are simple and non-tapering, with a rigid core of actin bundles (contrasting with the flexible, tapering and branched filopodia of nucleariids and the branched rhizoids and hyphae of fungi). In choanoflagellates and in the most primitive animals, namely sponges, they aggregate into a filter-feeding collar around the cilium or flagellum; this is thought to be an inheritance from their most recent common filozoan ancestor.[1]

References

- Shalchian-Tabrizi K.; Minge M.A.; Espelund M.; et al. (7 May 2008). Aramayo, Rodolfo (ed.). "Multigene phylogeny of choanozoa and the origin of animals". PLoS ONE. 3 (5): e2098. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002098. PMC 2346548. PMID 18461162.

- Laura Wegener Parfrey; Daniel J G Lahr; Andrew H Knoll; Laura A Katz (16 August 2011). "Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (33): 13624–9. doi:10.1073/PNAS.1110633108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3158185. PMID 21810989. Wikidata Q24614721.

- Hehenberger, Elisabeth; Tikhonenkov, Denis V.; Kolisko, Martin; Campo, Javier del; Esaulov, Anton S.; Mylnikov, Alexander P.; Keeling, Patrick J. (10 July 2017). "Novel Predators Reshape Holozoan Phylogeny and Reveal the Presence of a Two-Component Signaling System in the Ancestor of Animals". Current Biology. 27 (13): 2043–2050.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.006. PMID 28648822.

- Adl, Sina M.; Bass, David; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Agatha, Sabine; Berney, Cedric; Brown, Matthew W. (2018-09-26). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. ISSN 1066-5234. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- Tedersoo, Leho; Sánchez-Ramírez, Santiago; Kõljalg, Urmas; Bahram, Mohammad; Döring, Markus; Schigel, Dmitry; May, Tom; Ryberg, Martin; Abarenkov, Kessy (2018). "High-level classification of the Fungi and a tool for evolutionary ecological analyses". Fungal Diversity. 90 (1): 135–159. doi:10.1007/s13225-018-0401-0. ISSN 1560-2745.