Heterokont

Heterokonts are a group of protists (formally referred to as Heterokonta, Heterokontae or Heterokontophyta). The group is a major line of eukaryotes.[9][10] Most are algae, ranging from the giant multicellular kelp to the unicellular diatoms, which are a primary component of plankton. Other notable members of the Stramenopiles include the (generally) parasitic oomycetes, including Phytophthora of Great Famine of Ireland infamy and Pythium which causes seed rot and damping off.

| Heterokont | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ochromonas sp. (Chrysophyceae), with two unequal (heterokont) flagella. Mastigonemes not represented. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Infrakingdom: | Heterokonta Cavalier-Smith, 1986[1] |

| Typical classes | |

|

Colored groups (alga-like)

Colorless groups

| |

| Synonyms | |

The name "heterokont" refers to the type of motile life cycle stage, in which the flagellated cells possess two differently arranged flagella (see zoospore).

History

In 1899, Alexander Luther created "Heterokontae" for some algae with unequal flagella, today called Xanthophyceae.[11] Later, some authors (e.g., Copeland, 1956) would include other groups in Heterokonta, expanding its sense. The term continues to be applied in different ways, leading to Heterokontophyta being applied also to the phylum Ochrophyta. The term 'Stramenopile' was introduced in 1989 by Patterson [12] to overcome ambiguities that had (and continue to be) developed with the use of the term 'heterokont'. Consequently, heterokonts may be refrred to as stramenopiles.

The term 'heterokont' first emerged in the context of 19th century phycology. Over time, the scope of application has changed; especially when in the 1970's as ultrastructural studies revealed greater diversity among the algae with chromoplasts (= chlorophylls a and c) than had previously been recognized. At the same time, a protistological perspective was replacing the 19th century one based on the division of unicellular eukaryotes along inappropriate botanical/zoological lines. One consequence was that an array of heterotrophic organisms, many of which had not been previously considered as 'heterokonts' were seen as being related to the 'core heterokonts' (i.e. those having anterior flagella with stiff hairs). Newly recognized relatives included the parasitic opalines, proteromonads, and actinophryid heliozoa. They joined other heterotrophic protists, such as bicosoecids, labyrinthulids, and oomycete fungi, that were included by some as heterokonts and excluded by others. Rather than continue to use a name whose meaning had changed over time and was hence ambiguous, the name 'stramenopile' was introduced to refer to the clade of protists that had tripartite stiff (usually flagellar) hairs and all their descendents. Molecular studies confirm that the genes that code for the proteins of these hairs are exc;lusive to stramenopiles.[13] As the concept of 'Stramenopile' is based on a presumed apomorphy, it is stable and robust even when its composition changes. There is a widespread presumption, as here, that the terms 'stramenopile' and 'heterokont' are synonyms. They are not because they aredefined differently and despite compositional overlap, most applications of the names imply differing compositions.

Morphology

Motile cells

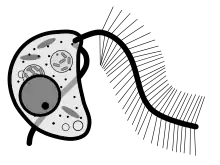

Many heterokonts are unicellular flagellates, and most others produce flagellated cells at some point in their lifecycles, for instance as gametes or zoospores. The name heterokont now refers to the characteristic form of these cells, which typically have two unequal flagella. The anterior flagellum is covered with one or two rows of lateral hairs or mastigonemes, which are tripartite (i.e. with a flexible basal insertion, a stiff hollow component, and tipped with fine delicate hairs ), while the posterior flagellum is smooth, and usually shorter, or sometimes reduced to a basal body. The flagella are inserted subapically or laterally, and are usually supported by four microtubule roots in a distinctive pattern. Opalines have many rows of flagella which do not have flagellar hairs. They are closely related to endosymbiotic proteromonad flagellates some of which have tripartite hairs extending from the body surface.

Mastigonemes are manufactured from glycoproteins in the endoplasmic reticulum before being transported to the anterior flagellar surface. When the hairy flagellum beats, the stiff mastigonemes are forced backwards and this creates a retrograde current, pulling the cell through the water or bringing in food.

The term mastigonemes refers to various types of flagellar hairs, but those of stramenopiles have a distinctive structure. It was treated as the evolutionary innovation that defined the stramenopiles, and although not initially so, it is increasingly treated as the defining characteristic of the heterokonts. Mastigonemes have been lost in a few heterkont lines, most notably the diatoms, opalines, and actinphryid heliozoa.

Chloroplasts

Many heterokonts are algae with chloroplasts surrounded by four membranes, which are counted from the outermost to the innermost membrane. The first membrane is continuous with the host's chloroplast endoplasmic reticulum, or cER. The second membrane presents a barrier between the lumen of the cER and the primary endosymbiont or chloroplast, which represents the next two membranes, within which the thylakoid membranes are found. This arrangement of membranes has led top hypothesis that heterokont chloroplasts were obtained from the reduction of a symbiotic red algal eukaryote, which had arisen by evolutionary divergence from the monophyletic primary endosymbiotic ancestor that is thought to have given rise to all eukaryotic photoautotrophs. The chloroplasts characteristically contain chlorophyll a and chlorophyll c, and usually the accessory pigment fucoxanthin, giving them a golden-brown or brownish-green colour. Because of this colour, they are referred to as 'chromoplasts' distinguishing them from chlorophyll B containing plastids of green algae, their descendents the higher plants, and euglenids.

Most basal heterokonts are colorless. This suggests that they diverged before the acquisition of chloroplasts within the group. However, fucoxanthin-containing chloroplasts are also found among the haptophytes. This led to hypotheses that all organisms with chlorophylla/c containing chloroplasts have a common phylogenetic history with cryptomonads, and should be taxopnomically grouped as the Chromista. Molecular studies do not confirm that the stramenopiles, haptophytes, and cryptomonads are sister taxa.[14] The current consensus is that the ancestral stramenopiles / heterokonts were heterophic and acquired chloroplats after their defining feature (the triparite hairs) appeared.

Classification

As noted above, classification varies considerably. Originally, the heterokont algae was used only for Xanthophytes. The concept morphed to include more lineages and considered by some as part of the kingdom Plantae and later, by others, as within the Protista. An example is:

- Division Chrysophyta

- Class Chrysophyceae (golden algae)

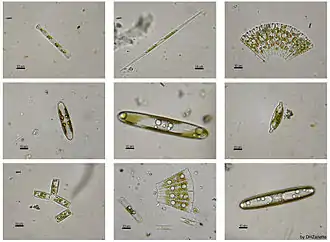

- Class Bacillariophyceae (diatoms)

- Division Phaeophyta (brown algae)

In this scheme, the Chrysophyceae is conceived of a very extensive group (Chrysophyte sensu lato) that was paraphyletic - as the diatoms and brown algae evolved from within the chrysophytes. Over time, various lineages have been given their own classes and often divisions. Recent systems often treat these as classes within a single division, called the Heterokontophyta, Chromophyta, or Ochrophyta. This is not universal, however; Round et al. treat the diatoms as a division.

The discovery that oomycetes and hyphochytrids are related to these algae, rather than fungi, as previously thought, has led many authors to include these two groups among the heterokonts. Should it turn out that they evolved from colored ancestors, the heterokont group would be paraphyletic in their absence. Once again, however, usage varies. David J. Patterson named this extended group the stramenopiles, characterized by the presence of tripartite mastigonemes, mitochondria with tubular cristae, and open mitosis. He used the stramenopiles as a prototype for a classification without Linnaean rank. Their composition has been essentially stable, but their use within ranked systems varies.

Thomas Cavalier-Smith treats the heterokonts as identical in composition with the stramenopiles; this is the definition followed here. He has proposed placing them in a separate kingdom, the Chromalveolata, together with the haptophytes, cryptomonads, and alveolates. This is one of the most common revisions to the five-kingdom system, but has not been adopted, because Chromalveolata is not a monophyletic group. A few treat the Chromalveolata as identical in composition with the heterokonts, or list them as a kingdom Stramenopila.

Some sources divide the heterokonts into the autotrophic Ochrophyta and heterotrophic Bigyra and Pseudofungi.[15] However, some modifications to these classifications have been suggested.

The name Heterokonta can be confused with the (much older) name Heterokontae, which is generally equivalent to the Xanthophyceae, a limited subset of the Heterokonta.[16]

The simplified classification of the group according to Adl et al. (2012), in which heterokonts (using the term Stramenopiles) are part of a larger clade that embraces Alveolates and Rhizaria, is:[17]

- SAR

- Stramenopiles Patterson, 1989, emend. Adl et al., 2005

- Opalinata Wenyon, 1926, emend. Cavalier-Smith, 1997 (Slopalinida Patterson, 1985)

- Blastocystis Alexeev, 1911

- Bicosoecida Grassé, 1926, emend. Karpov, 1998

- Placidida Moriya et al., 2002

- Labyrinthulomycetes Dick, 2001

- Hyphochytriales Sparrow, 1960

- Peronosporomycetes Dick, 2001 (Öomycetes Winter, 1897, emend. Dick, 1976)

- Actinophryidae Claus 1874, emend. Hartmann 1926

- Bolidomonas Guillou & Chrétiennot-Dinet, 1999 (Bolidophyceae in Guillou et al., 1999)

- Chrysophyceae Pascher, 1914

- Dictyochophyceae Silva, 1980

- Eustigmatales Hibberd, 1981

- Pelagophyceae Andersen & Saunders, 1993

- Phaeothamniophyceae Andersen & Bailey, in Bailey et al., 1998

- Pinguiochrysidales Kawachi et al., 2003

- Raphidophyceae Chadefaud, 1950, emend. Silva, 1980

- Synurales Andersen, 1987

- Xanthophyceae Allorge, 1930, emend. Fritsch, 1935 (Heterokontae Luther, 1899, Heteromonadea Leedale, 1983, Xanthophyta Hibberd, 1990)

- Phaeophyceae Hansgirg, 1886 (not Kjellman, 1891, not Pfitzer, 1894)

- Schizocladia Henry et al., in Kawai et al., 2003 (Schizocladales Kawai et al., 2003) (M)

- Diatomea Dumortier, 1821 (= Bacillariophyta Haeckel, 1878)

- Alveolata

- Rhizaria

- Stramenopiles Patterson, 1989, emend. Adl et al., 2005

Phylogeny

Based on the following works of Ruggiero et al. 2015 & Silar 2016.[18][19][20]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

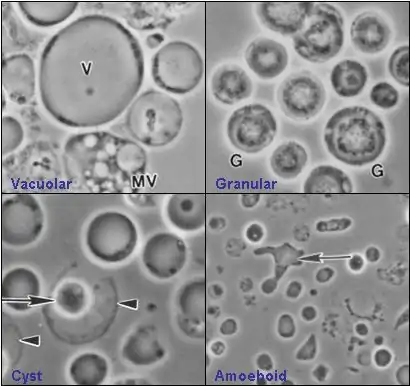

Blastocystis hominis (Blastocystea)

Blastocystis hominis (Blastocystea)_Microscopy.tif.jpg.webp)

Potatoes with Phytophthora (Oomycetes)

Potatoes with Phytophthora (Oomycetes)

Actinophrys sol (Actinophryida)

Actinophrys sol (Actinophryida)

Dinobryon sp. (Chrysophyceae)

Dinobryon sp. (Chrysophyceae) Synura sp. (Synurophyceae)

Synura sp. (Synurophyceae)

Fucus distichus (Phaeophyceae)

Fucus distichus (Phaeophyceae) Pelagophycus porra (Phaeophyceae)

Pelagophycus porra (Phaeophyceae)

References

- Cavalier-Smith, T. (1999). "The kingdom Chromista, origin and systematics". In Round, F.E.; Chapman, D.J. (eds.). Progress in Phycological Research. 4. Elsevier. pp. 309–347. ISBN 978-0-948737-00-8.

- Patterson, D.J. (1989). "Stramenopiles: Chromophytes from a protistan perspective". In Green, J.C.; Leadbeater, B.S.C.; Diver, W.L. (eds.). The chromophyte algae: Problems and perspectives. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198577133.

- Vørs, N (1993). "Marine heterotrophic amoebae, flagellates and heliozoa from Belize (Central America) and Tenerife". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 40 (3): 272–287. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04917.x.

- David, J.C. (2002). "A preliminary catalogue of the names of fungi above the rank of order". Constancea. 83: 1–30.

- van den Hoek, C.; Mann, D.G.; Jahns, H.M. (1995). Algae An Introduction to Phycology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30419-1.

- Alexopoulos, C.J.; Mims, C.W.; Blackwell, M. (1996). Introductory Mycology (4th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0471522294.

- Dick, M.W. (2013). Straminipilous Fungi: Systematics of the Peronosporomycetes Including Accounts of the Marine Straminipilous Protists, the Plasmodiophorids and Similar Organisms. Springer. ISBN 978-94-015-9733-3.

- "Stramenipila M.W. Dick (2001)". MycoBank. International Mycological Association.

- "stramenopiles". Retrieved 2009-03-08.

- Hoek, C. van den; D. G. Mann; H. M. Jahns (1995). Algae: An Introduction to Phycology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 104, 124, 134, 166. ISBN 978-0-521-31687-3.

- Luther, Alexander F. (1899). Über Chlorosaccus eine neue Gattung der Süsswasseralgen nebst einiger Bemerkungen zur Systematik verwandter Algen. Stockholm: Norstedt. p. 1-22.

- Patterson, D. J. 1989. Stramenopiles: chromophytes from a protistological perspective. In: Green, J.C., Leadbeater, B.S.C. & Diver, W. L. 1989. The chromophyte algae: problems and perspectives. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 357–379

- Hee, W.Y., Blackman, L.M. & Hardham, A.R. Characterisation of Stramenopile-specific mastigoneme proteins in Phytophthora parasitica. Protoplasma 256, 521–535 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-018-1314-1

- Derelle R, López-García P, Timpano H, Moreira D. A Phylogenomic Framework to Study the Diversity and Evolution of Stramenopiles (=Heterokonts). Mol Biol Evol. 2016 Nov;33(11):2890–2898. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw168. Epub 2016 Aug 10. PMID: 27512113; PMCID: PMC5482393

- Riisberg I, Orr RJ, Kluge R, et al. (May 2009). "Seven gene phylogeny of heterokonts". Protist. 160 (2): 191–204. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2008.11.004. PMID 19213601.

- Blackwell, W. H. (2009). "Chromista revisited: A dilemma of overlapping putative kingdoms, and the attempted application of the botanical code of nomenclature" (PDF). Phytologia. 91 (2).

- Adl, Sina M; Simpson, Alastair G. B; Lane, Christopher E; Lukeš, Julius; Bass, David; Bowser, Samuel S; Brown, Matthew W; Burki, Fabien; Dunthorn, Micah; Hampl, Vladimir; Heiss, Aaron; Hoppenrath, Mona; Lara, Enrique; Le Gall, Line; Lynn, Denis H; McManus, Hilary; Mitchell, Edward A. D; Mozley-Stanridge, Sharon E; Parfrey, Laura W; Pawlowski, Jan; Rueckert, Sonja; Shadwick, Laura; Schoch, Conrad L; Smirnov, Alexey; Spiegel, Frederick W (2012). "The Revised Classification of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 59 (5): 429–514. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x. PMC 3483872. PMID 23020233.

- Ruggiero; et al. (2015). "Higher Level Classification of All Living Organisms". PLoS ONE. 10 (4): e0119248. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019248R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119248. PMC 4418965. PMID 25923521.

- Silar, Philippe (2016). "Protistes Eucaryotes: Origine, Evolution et Biologie des Microbes Eucaryotes". HAL Archives-ouvertes: 1–462.

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Scoble, Josephine Margaret (2013). "Phylogeny of Heterokonta: Incisomonas marina, a uniciliate gliding opalozoan related to Solenicola (Nanomonadea), and evidence that Actinophryida evolved from raphidophytes". European Journal of Protistology. 49 (3): 328–353. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2012.09.002. PMID 23219323.