First Battle of Champagne

The First Battle of Champagne (French: 1ère Bataille de Champagne) was fought from 20 December 1914 – 17 March 1915 in World War I in the Champagne region of France and was the second offensive by the Allies against the German Empire since mobile warfare had ended after the First Battle of Ypres in Flanders (19 October – 22 November 1914). The battle was fought by the French Fourth Army and the German 3rd Army. The offensive was part of a French strategy to attack the Noyon Salient, a large bulge in the new Western Front, which ran from Switzerland to the North Sea. The First Battle of Artois began on the northern flank of the salient on 17 December and the offensive against the southern flank in Champagne began three days later.

| First Battle of Champagne | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of the World War I | |||||||

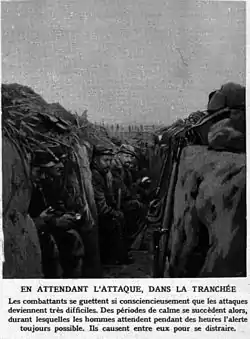

Waiting for the attack, in the trench. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Fourth Army | 3rd Army | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 93,432 | 46,100 | ||||||

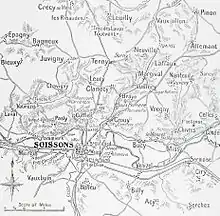

Champagne Champagne-Ardenne, a former administrative region of France, in the north-east, bordering Belgium | |||||||

Background

Strategic developments

By early November, the German offensive in Flanders had ended and the French began to consider large offensive operations. Attacks by the French would assist the Russian army by forcing the Germans to keep more troops in the west. After studying the possibilities for an offensive, the Operations Bureau of Grand Quartier Général (GQG, French army headquarters) reported on 15 November. The Bureau recommended to General Joseph Joffre a dual offensive, with attacks in Artois and Champagne, to crush the Noyon salient. The report noted that the German offensive in the west was over and four to six corps were being moved to the Eastern Front.[1]

Despite shortages of equipment, artillery and ammunition, which led Joffre to doubt that a decisive success could be obtained, it was impossible to allow the Germans freely to concentrate their forces against Russia. Principal attacks were to be made in Artois by the Tenth Army (General Louis de Maud'huy) towards Cambrai and by the Fourth Army (General Fernand de Langle de Cary) in Champagne, from Suippes towards Rethel and Mézières, with supporting attacks elsewhere. The objectives were to deny the Germans an opportunity to move troops and to break through in several places, to force the Germans to retreat.[2]

Battle

Fourth Army

After skirmishes the battle began on 20 December 1914 when the XVII and I Colonial Corps attacked and made small gains. On 21 December, the XII Corps failed to advance, because most gaps in the German barbed wire were found to be covered by machine-guns. The attack by XII Corps was stopped and the infantry began mining as the artillery bombarded German defences. After several days of attacks, which obtained more small pieces of territory, the main effort was moved by de Cary to the centre near Perthes and a division was added between XVII Corps and I Colonial Corps. On 27 December, Joffre sent the IV Corps to the Fourth Army area, which made it possible for de Langle to add another I Corps division to the front line. On 30 December, the French began a new attack as the Germans counter-attacked II Corps on the right flank, took three lines of defence and inflicted many casualties. Next day, II Corps retook most of the lost ground but the Germans made four big counter-attacks against the Fourth Army, which disorganised the French offensive.[3] Over the next few days, the French used artillery-fire to keep pressure on the Germans. A counter-attack on the night of 7/8 January drove the French out of a salient west of Perthes, until another French attack recovered most of the lost ground. French attacks continued for another two weeks, took small amounts of ground and drove off several German counter-attacks but had made few gains, by the time that the offensive was suspended, on 13 January.[4]

Supporting attacks

Supporting attacks in Artois and Champagne by the Second Army, Eighth Army and the troops on the coast at Nieuport supported the Tenth Army at Arras in the First Battle of Artois (17 December 1914 –13 January 1915). The Fourth Army attacks were assisted by the Army Detachment of the Vosges, which had also had little success. The armies on supporting fronts had far fewer guns and an attack by the XI Corps of the Second Army on 27 December, had no artillery support. In the Vosges, French artillery did not begin to fire until the two attacking divisions began to advance. All of the supporting attacks were costly failures.[4]

German counter-attacks

In mid-January a German attack began to the north of Soissons, on the route to Paris but the attack was made by small numbers of troops, to conserve reserves for operations on the Eastern Front and the French defenders repulsed the attack. In late January, a German attack was made against the Third Army, which was defending the heights of Aubréville close to the main railway to Verdun. Having been pushed back, the French counter-attacked six times and lost 2,400 casualties. The German attack failed to divert French troops from the flanks of the Noyon Salient.[5]

Aftermath

Analysis

De Langle wrote a report on the campaign, in which he asserted that the army had followed the principle of avoiding a mass offensive and instead, made a series of attacks against points of tactical significance. When such operations succeeded it had become necessary to make similar preparations for a new attack, by digging approach trenches and destroying German field defences with artillery-fire. Obtaining a breakthrough by "continuous battle" was impossible and de Langle claimed that methodical successive attacks, to capture points of tactical importance, would have more effect. Joffre replied that the failure of the offensive was due to inadequate artillery support and too few infantry. Attacks had been made on narrow fronts of a few hundred yards, despite the offensive taking place on a 12 mi (19 km) front and left infantry far too vulnerable to massed artillery-fire. De Langle was ordered quickly to make several limited attacks but Joffre told Poincaré the French president, that a war of movement was a long way off.[6]

Casualties

In 2005, Robert Foley recorded c. 240,000 French casualties in February with c. 45,000 German losses, using data from Der Weltkrieg, the German official history.[7][8] In 2012, Jack Sheldon recorded 93,432 French casualties and 46,100 German.[9]

Footnotes

- Doughty 2005, pp. 124–125.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 126–127.

- Doughty 2005, p. 132.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 132–133.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 134–135.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 133–134.

- Foley 2007, p. 157.

- Humphries & Maker 2010, p. 60.

- Sheldon 2012, pp. 41, 43.

References

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Foley, R. T. (2007) [2005]. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun: Erich von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870–1916 (pbk. ed.). Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-04436-3.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2010). Germany's Western Front, 1915: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. II (1st ed.). Waterloo Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-259-4.

- Sheldon, J. (2012). The German Army on the Western Front 1915 (1st ed.). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-466-7.

Further reading

- Clayton, A. (2003). Paths of Glory. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35949-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Battle of Champagne. |