Flathead Indian Reservation

The Flathead Indian Reservation, located in western Montana on the Flathead River, is home to the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d'Oreilles tribes – also known as the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation. The reservation was created through the July 16, 1855, Treaty of Hellgate.

Flathead Native American Reservation | |

|---|---|

View northeastward across Hungry Horse Reservoir onto the Flathead Range, Montana | |

Flag | |

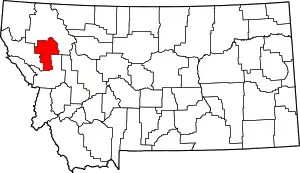

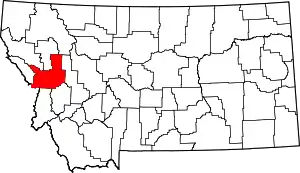

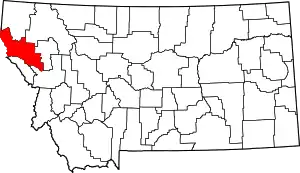

Location in Montana | |

| Tribe | Confederated Salish and Kootenai |

| Country | United States |

| State | Montana |

| Counties | Flathead Lake Missoula Sanders |

| Established | 1855 |

| Headquarters | Pablo |

| Government | |

| • Body | Tribal Council |

| • Chairman | Ron Trahan |

| • Vice-Chairman | Leonard Gray |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5,020 km2 (1,938 sq mi) |

| Population (2017)[2] | |

| • Total | 29,218 |

| • Density | 5.8/km2 (15/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-6 (MDT) |

| Website | cskt.org |

It has land in four of Montana's counties: Lake, Sanders, Missoula, and Flathead, and controls most of Flathead Lake.[3] The Flathead Indian Reservation, west of the Continental Divide, consists of 1,938 square miles (5,020 km2) (1,317,000 acres (533,000 ha)) of forested mountains and valleys.[4]

History

Native Americans have lived in Montana for more than 14,000 years, based on archaeological findings. The Bitterroot Salish came from the West Coast, whereas the Kootenai lived mostly in the interior of present-day Idaho, Montana, and Canada. The Kootenai left artifacts in prehistoric time. One group of the Kootenai in the northeast lived mainly on bison hunting. Another group lived on the rivers and lakes of the mountains in the west. When they moved east, they could rely less on salmon fishing, but turned to eating plants and bison. During the 18th century, the Salish and the Kootenai tribes shared gathering and hunting grounds.[5] As European-American settlers entered the area, the different cultures of peoples came into conflict.

In 1855 the United States (US) made the Treaty of Hellgate, by which it set aside a reservation solely for use of the Flathead, encompassing an area including much of Flathead Lake. By the late 19th and early 20th century, the federal government had adopted a policy of allotting lands to individual Indian households from their communal holdings, in order to encourage subsistence farming and adoption of European-American ways. Such allotments took place in what became the state of Oklahoma, former Indian Territory, in order to extinguish Indian land claims.

Although the Flathead opposed such European-style allotments and farming, the US Congress passed the 1904 Flathead Allotment Act. After allotments of land to individual households of members on the tribal rolls, the government declared the rest of the communal land to be "surplus" and opened the reservation to homesteading by whites. United States Senator Joseph M. Dixon of Montana played a key role in getting this legislation passed. Its passage caused much resentment by the Flathead, and the allotment of reservation lands remains "a very sensitive issue". The Flathead still would like to regain control of their reservation lands.[6]

The area was favorably compared to the Yakima River Valley in Washington State. Thousands of acres on the reservation were reserved for town sites, schools and the National Bison Range. The Flathead were given first choice of either 80 or 160 acres of land per household. The rest was made open to whites in 1910. A total of 81,363 applications by whites were received for 1,600 parcels of land. The applications were placed in plain brown envelopes, piled onto a pallet, and three young girls drew 6,000 of them, choosing who would have a chance to homestead on the land. The first 3,000 were notified in the spring and the second 3,000 were notified in the fall. But, lottery winners took only 600 tracts, leaving 1,000 tracts still open. These were taken in what the tribe considers a subsequent "land grab".

The distribution of their lands did not end the Native American problems with whites. According to their treaty, the tribes have the right to off-reservation hunting, but the state believed it could regulate those activities. State game wardens were responsible for a confrontation in 1908 with a small Pend d'Oreilles hunting party, which resulted in deaths of four of the Native Americans, in what is known as the Swan Valley Massacre.[6][5] A court challenge to their hunting rights reached the US Supreme Court, which upheld tribal treaty rights to hunt off-reservation in their former territory.

Geography and ecology

All but the northern tip of Flathead Lake is part of the reservation. Flathead Lake lies in the northeast corner of the reservation, with most of the reservation to the south and west of the lake.[7] Polson, the county seat of Lake County, is located at the southern end of the lake and within the reservation boundaries.

Part of the Mission Mountains range is on the reservation. The western end of the range is protected by the Mission Mountains Tribal Wilderness and the eastern end of the range is protected by the Mission Mountains Wilderness. Parts of the Bob Marshall Wilderness are nearby.[8]

Recent years have seen a decline in the numbers of native fish species, which include: bull trout, westslope cutthroat trout, northern whitefish, and northern pikeminnow. Non-native species include: yellowstone cutthroat trout, brook trout, rainbow trout, brown trout, lake trout, lake whitefish, black bullhead, kokanee salmon, yellow perch, northern pike, largemouth bass, and smallmouth bass.[9]

The tribe prohibits hunting furbearing animals on the reservation.[10] The tribe permits hunting by non-natives of the following birds: Hungarian partridge, pheasants, ducks, geese, mergansers, and coots.[9] Other animals that can not be hunted by non-natives are: elk, white-tailed deer, mule deer, grizzly bear, and moose. Wolves, bison, swans, and falcons are also present.[11]

Demographics

The total population of the reservation was 28,324 as of the 2010 census, an 8% increase over the 2000 census. Some 9,138 persons living there identified as Native American; a total of 19,221 identified as other ethnicities, outnumbering tribal members by 2:1.[12][13] The largest community on the reservation is the city of Polson, which is also the county seat of Lake County. The seat of government of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation is Pablo.[14]

Economy

The tribes derive income from selling timber and from operating a variety of businesses:

- Gray Wolf Peak casino in the south of the reservation between Arlee and Evaro,[15]

- KwaTaqNuk ("where the water leaves the lake") resort and casino in Polson,[16]

- S&K Technologies, a defense technology firm with its headquarters in St. Ignatius and five subsidiary companies in the US and Saudi Arabia[17]

- S&K Electronics in Pablo, an electronics manufacturer established in 1984,[18]

- S&K Holding, a leasing and financing firm[19]

In 2015, the tribes acquired the former Kerr Dam, renaming it as the Seli’š Ksanka Qlispe’ Dam. They are the first tribe to own a hydroelectric dam. It generates hydroelectric power for the region.[20] They had previously worked with and shared revenues with the owner and operator of the dam, but decided to acquire it so they would have sole interest.[21][22]

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation also operate and maintain Mission Valley Power, a federally owned electricity provider.[23]

Salish Kootenai College, a tribally controlled college, has been established in Pablo. It offers two- and four-year degrees.[24][7].

Points of interest

- Flathead Indian Museum, St. Ignatius[24][7]

- Flathead Lake State Park[24][7]

- The Garden of One Thousand Buddhas

- Kicking Horse Reservoir

- Mission Mountains Tribal Wilderness[7]

- The National Bison Range/Pablo National Wildlife Refuge, Moiese[24][7]

- Ninepipe National Wildlife Refuge and State Wildlife Management Area[24][7]

- St. Ignatius Mission, St. Ignatius[7]

- The People's Center, Pablo[24]

Communities

There are 26 places (including CDPs) on the reservation that are officially recognized by the Census Bureau. Only eight of them are majority Flathead. Today the Flathead own about 2/3 of the land on the reservation. After the allotment and homesteading at the turn of the 20th century, whites gained ownership over most of the land on the reservation. Since the late 20th century, the tribe has been steadily buying back the land over many years.[25]

References

- "Government – Tribal Council". Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. "My Tribal Area". United States Census Bureau.

- "Local and Social Services" (PDF). Lake County, Montana. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- "Flathead Indian Reservation". Online Highways. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- "The Montana Dinosaur Trail". Montana Dinosaur Trail. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- "Flathead Reservation Marks Century of White Settlement". The Missoulian. September 26, 2010. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- "S'elish-Ktunaxa-Flathead". Visit Montana. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- "The Mission Mountains". Big Sky Fishing. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- "Flathead Indian Reservation Fishing, Bird Hunting, and Recreation Regulations". Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. Archived from the original on March 27, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2011. includes detailed map of the reservation

- Becker, Dale (January 27, 2021). "Tribal wildlife management on the Flathead Indian Reservation". Char-Koosta News. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- "Conserving Wildlife (and Culture) on the Flathead Indian Reservation". Montana Outdoors. Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. Archived from the original on 2011-04-01. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- "Flathead CCD". United States Census Bureau. 2000. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- "Census shows growth at 4 Montana reservations". Helena Independent Record. March 28, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- "Historic Saint Mary's Mission". Saint Mary's Mission. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- "Gray Wolf Peak Casino - New State-of-the-art gaming". Gray Wolf Peak Casino.

- "Kwataqnuk Flathead Lake Resort & Casino - Stay-N-Play". Kwataqnuk.com.

- "Companies & Services". Sktcorp.com.

- "S&K Electronics". Skecorp.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-08-08. Retrieved 2018-05-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Missoulian: CSKT to pay $18.3M for Kerr Dam; new name planned, The Missoulian, 5 March 2014

- "Montana tribes will be the first to own a hydroelectric dam", High Country News, 25 November 2013

- "Federal commission OKs 2nd new name for former Kerr Dam", Missoulian, 10 November 2015

- Mission Valley Power Operations Manual Archived 2018-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, PDF, Introduction, page 7

- "Flathead Indian Reservation". Montana Kids. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- "Flathead Reservation". Anishinabe History. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

Further reading

- Ronan, Peter (1890). Historical sketch of the Flathead Indian Nation from the year 1813-1890: embracing the history of the establishment of St. Mary's Indian Mission in the Bitter Root Valley, Mont.: with sketches of the missionary life of Father Ravalli and other early missionaries: wars of the Blackfeet and Flatheads and sketches of history, trapping and trading in the early days. Helena, MT: Journal Publishing Co. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- Smead, William Henry (1905). Land of the Flatheads; a sketch of the Flathead Reservation, Montana, its past and present. Missoula, MT: Press of the Daily Missoulian. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- Broderick, Therese (1909). The brand, a tale of the Flathead reservation. Seattle: Alice Harriman Company. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- Jones, Tom (1909). The last of the buffalo: comprising a history of the buffalo herd of the Flathead Reservation, and an account of the Great Round Up, with illustrations. Cincinnati, Ohio: Publisher Scenic Souvenirs. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation. |