Fossil Lake (Oregon)

Fossil Lake (designated by the Bureau of Land Management as Fossil Lake Area of Critical Environmental Concern) is a dry lakebed in the remote high desert country of northern Lake County in the U.S. state of Oregon. During the Pleistocene epoch, Fossil Lake and the surrounding basin were covered by an ancient lake. Numerous animals used the lake resources. Over time, the remains of many of these animals became fossilized in the lake sediments. As a result, Fossil Lake has been an important site for fossil collection and scientific study for well over a century. Over the years, paleontologists have found the fossil remains of numerous mammals as well as bird and fish species there. Some of these fossils are 2 million years old.

| Fossil Lake | |

|---|---|

Fossil Lake interpretive sign | |

Fossil Lake location in Oregon | |

| Location | Lake County, Oregon, United States |

| Coordinates | 43.3258°N 120.4909°W |

| Area | 10.2 sq mi (26 km2) |

| Elevation | 4,295 ft (1,309 m) |

| Governing body | Bureau of Land Management |

Location

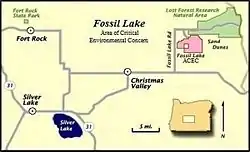

Fossil Lake is located in a remote area of northern Lake County, Oregon. It is 19 miles (31 km) from the unincorporated community of Christmas Valley by road. Fossil Lake is approximately 65 miles (105 km) southeast of Bend and 79 miles (127 km) north of Lakeview in straight-line distance.[1][2]

From Christmas Valley, visitors travel east on County Road 5–14 (Christmas Valley-Wagontire Road) for 8 miles (13 km); then turn north on County Road 5-14D (Fossil Lake Road). Travel 8 miles (13 km) and then turn east onto the County Road 5-14E (Lost Forest Road), a gravel road. After approximately 1.7 miles (2.7 km), turn south onto a rough unmarked dirt road. The Fossil Lake interpretive sign is approximately 1.4 miles (2.3 km) from the turnoff. Vehicles are not allowed in the Fossil Lake Area of Critical Environmental Concern, so visitors must walk the last 150 yards (140 m) to the Fossil Lake interpretive sign. Fossil Lake itself is 1 mile (1.6 km) southwest of the sign.[1][2]

Geology and natural history

The bedrock beneath the Fossil Lake area was created by basalt flows laid down during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. After a period of intense faulting during the middle Pleistocene, a large basin area created by horst and graben faulting was modified by erosion and sedimentation. This basin filled with water during the wet climatic periods of the Pleistocene and post-Pleistocene to a depth of 200 feet (61 m). Over the past 3,200 years, the surface water in the Christmas Valley basin including Fossil Lake has completely dried up, leaving a high-desert environment.[1][3][4]

The lakebed at Fossil Lake was formed during the post-Pleistocene period from lake sediments and alluvial materials. Pumice sands from Mount Mazama and Newberry Crater also appear in the surface soils throughout the Fossil Lake area. The surface soils are underlain by a hard calcium carbonate caliche layer several inches thick. This subsurface caliche layer is impervious to water drainage and is seldom penetrated by roots. This locally unique water-retentive sub-surface structure has helped the ponderosa pines in nearby Lost Forest Research Natural Area survive in the high-desert environment.[3][5]

In 1877, there were still two small seasonal ponds at the Fossil Lake site surrounded by a large dry lakebed. The two ponds were called the Fossil Lakes. Since then, both ponds have dried up completely. In addition, the site name is now singular and only applies to the western dry-pond area.[6]

Today, the Fossil Lake site is a dry lakebed above fossil-bearing deposits in the Christmas Valley basin. The area is generally flat with gentle swales. The elevation of the lakebed is 4,295 feet (1,309 m) above sea level. There are large moving sand dunes east of the lakebed. These dunes are made up of lacustrine sediments, aeolian deposits, and alluvial materials with large amounts of volcanic pumice and ash mixed into fine sand that have been blown off the surface of Fossil Lake.[5][7]

History

The first settlers arrived in the Christmas Lake Valley around 1865.[8] In June 1877, John Whiteaker (a former governor of Oregon) visited the Christmas Valley basin. During the trip, Whiteaker explored the Fossil Lake area, where he found a large dry lakebed with two small alkali ponds in low spots. Whiteaker named the ponds the Fossil Lakes. In addition, he found numerous exposed fossils throughout the area, including elephant, camel, horse, and elk fossils, as well as fossils from animals that Whiteaker could not identify. He noted that horse and bird fossils were particularly plentiful. He also found ancient human artifacts. Whiteaker reported that fossils were scattered across a large swath of desert running from southwest to northeast. He estimated that the fossil beds were 1 mile (1.6 km) wide and over 4 miles (6.4 km) long. After his trip, Whiteaker delivered his fossils to Thomas Condon, a well-known paleontologist and professor at the University of Oregon.[6][9]

Later that year, Whiteaker's son, J.C. Whiteaker, returned to Fossil Lake with professor Condon. The goal of this second expedition was to more carefully examine and record the numerous fossils scattered around the Fossil Lake site. Condon's discoveries at Fossil Lake attracted the attention of other well-known paleontologists.[6][10][11][12]

After the first site surveys in 1877, numerous paleontologists have visited Fossil Lake to collect fossils and conduct research.[1] In 1879, Professor Edward D. Cope of the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences visited Condon at the University of Oregon and then went to Fossil Lake to collect fossils.[11][12][13] Other paleontologists who collected at Fossil Lake during the latter part of the 19th century include O. C. Marsh of Yale University; Charles H. Sternberg, an author and amateur paleontologist; Cope's pupil Jacob L. Wortman of the American Museum Of Natural History; and Robert W. Shufeldt, curator of the Army Medical Museum. Both Sternberg and Wortman led expeditions that collected for professor Cope. The Smithsonian Institution also began research at Fossil Lake in the late 1800s.[7][11][14][15] In 1901, Annie M. Alexander visited Fossil Lake to collect fossils. She sent her specimens to University of California.[16] During this period, local settlers reported that fossils were often removed by the wagon load.[14]

After 1906, the number of homesteads in the Christmas Valley basin began to increase. In that year, a post office was opened at Cliff, just north of Fossil Lake. Settlers used the Fossil Lake area for grazing sheep, cattle, and horses. Due to the harsh high-desert conditions, most of the settlers had abandoned their farms by 1920. That was the year the Cliff post office was closed. A prolonged drought in the 1920s and 1930s put an end to dry farming in the region.[8][17][18]

Additional fossil collection and research was conducted in the early 20th century. In 1907, David S. Jordan identified some of the fish fossils from the site. In 1911, Loye Holmes Miller identified and described a number of new bird fossils. Stufeldt identified more bird fossils in 1913. He also corrected some misidentified mammal fossils found during previous expeditions. Miller, Oliver P. Hay, and John C. Merriam also studied the age of the Fossil Lake specimens, concluding that the large number of extinct species indicted that the fossil period was older than previously thought. In addition, Chester Stock and E. L. Furlong conducted summers digs at the site of 1923 and 1924. Stock and Furlong sent their finds to the University of California.[14][16]

In 1977, the Bureau of Land Management placed a temporary ban on vehicles in the Fossil Lake area. The restriction applied to 6,560 acres (2,650 ha) around the dry lakebed. In 1979, the Bureau of Land Management made the vehicle ban permanent.[1][4][19] In 1983, the Bureau of Land Management joined Fossil Lake, the neighboring Lost Forest Research Natural Area, and the Christmas Valley Sand Dunes into a single Area of Critical Environmental Concern. Collecting fossils in the Fossil Lake Area of Critical Environmental Concern without a permit from the Bureau of Land Management is prohibited.[1][5]

In early 1990s, the Bureau of Land Management began working with the South Dakota School of Mines to salvage fossils and conduct paleontological research at Fossil Lake. This collaboration lasted well over a decade. The fossils collected during that project are housed at the South Dakota School of Mines campus in Rapid City, South Dakota.[7]

In 2017, a team from the University of Oregon with the assistance of the Bureau of Land Management discovered a trail of Columbian mammoth footprints. The track included 117 individual mammoth prints in a 66 feet (20 m) by 25 feet (7.6 m) area of the lakebed. Scientists believe the tracks were made approximately 43,000 years ago.[20]

Fossils

The fossil-bearing deposits at Fossil Lake cover at least 10,000 acres (4,000 ha). Over the years, there have been numerous expeditions to collect fossils at the Fossil Lake site. The site has produced more Holocene fossils than any other location in the world except the La Brea Tar Pits in California.[7] Fossil discoveries have included at least 23 mammal species,[16] 74 bird species, 7 fish species, and 11 mollusk species. Some of the large mammal fossils found at the site include Columbian mammoths, ground sloths, dire wolves, giant beavers, pre-historic bison, three species of camels, several horse species, peccary, and an extinct bear. Bird fossils include flamingos, pelicans, and swans, and large eagle species. Fish fossils include tui chub and several salmon species. Two-thirds of the fossil species collected at Fossil Lake are extinct.[1][4][7][21]

The extent of the fossil beds at the Fossil Lake site is still unknown; stratigraphically specific rock layers laid down at different periods each contain characteristic fossils of different animals. The fossil deposits from the Holocene epoch are between 8,000 and 50,000 years old. There are also Fossil Lake artifacts that indicate that humans may have hunted in this area near the end of this period. Some prey may have been large mammals that are now extinct. The oldest fossils from the site date back to the Pleistocene epoch. These fossils are up to 2 million years old.[4][7]

The Bureau of Land Management has identified several environmental concerns with regard to the Fossil Lake site. First, the fossil deposits extend beyond the boundary of the existing restricted area. As a result, there is a risk that vehicles or grazing livestock may damage unprotected fossils. Second, illegal fossil collecting is a potential problem. Finally, loose surface sediments at Fossil Lake continue to erode, exposing new fossils each year. When fossils are first exposed, they are often found as articulated skeletons. However, the remains are quickly scattered due to wind action. Sandy sediments carried by the wind also cause rapid weathering once the fossils are exposed. As a result, scientists try to collect the newly exposed fossils as soon as possible.[7]

Today, large fossil collections from the Fossil Lake site are maintained by the University of Oregon, the Smithsonian Institution, the South Dakota School of Mines, the University of California at Los Angeles, and the University of California at Berkeley.[7][12][22]

Environment

Based on National Weather Service data recorded at Cliff between 1908 and 1916 and other nearby weather reporting stations, the mean annual temperature in the Fossil Lake area is 43 °F (6 °C). The hottest and driest months are July and August, with a peak average temperature of 63 °F (17 °C). The coldest months are December and January. The average daily temperature in December is 30 °F (−1 °C) and 28 °F (−2 °C) in January. The mean annual precipitation at Fossil Lake is 8.7 inches (22 cm) per year. The wettest months are December and January, with a smaller peak period in May and June. However, weather patterns in this area are very erratic. For example, there was an extremely severe drought throughout the 1920s and early 1930s.[3]

The Fossil Lake area supports a plant community dominated by big sagebrush, low sagebrush, silver sagebrush, green rabbitbrush (also called yellow rabbitbrush), rubber rabbitbrush, and greasewood. There are a number of perennial grasses common in the Fossil Lake area, including Sandberg bluegrass, needle-and-thread grass, Indian ricegrass, creeping wildrye, and invasive cheatgrass. Perennial flowering plants found in the Fossil Lake area include prickly-phlox, lemon scrufpea common wooly sunflower, and Townsend daisy, and spiny hopsage.[23][24]

Wildlife

The animal population around Fossil Lake is typical of the high desert country of south-central Oregon. The larger mammals include pronghorn, American badger, and coyotes. Black-tailed jackrabbits, Ord's kangaroo rats, deer mice, Great Basin pocket mice, and northern grasshopper mice are among the smaller animals found in the Fossil Lake area. There also 13 bat species that live in the desert around Fossil Lake.[25][26] In 1917, a diminutive bear was killed near Fossil Lake. Originally, it was thought that the bear might be a unique species, a lava bear. A photograph of the bear was published in Oregon Sportsman magazine in October 1917. Eventually, it was determined that the specimen was an unusually small American black bear stunted from malnutrition.[27][28][29][30]

Fossil Lake is home to a number of bird species as well. They include greater sage-grouse, black-billed magpie, pinyon jay, Brewer's blackbird, American robin, mountain bluebird, sage thrasher, Sagebrush sparrow, and loggerhead shrike. There are also birds of prey such as prairie falcon, red-tailed hawks, and golden eagles.[25][26]

There are a number of reptiles found in the Fossil Lake area, both snakes and lizards. Snakes found in the area around Fossil Lake include western rattlesnakes, gopher snakes, striped whipsnakes, and night snakes. Common lizards include sagebrush lizards, short-horned lizards, side-blotched lizards, western fence lizards, and western skinks.[26]

References

- Lost Forest Research Natural Area (PDF), Christmas Valley Sand Dunes Area of Critical Environmental Concern, Lakeview District, Bureau of Land Management, United States Department of Interior, Lakeview, Oregon, 2005.

- Fossil Lake geo-location, Oregon topographic map, United States Geological Survey, United States Department of Interior, Reston, Virginia; displayed via ACME mapper, www.acme.com, 5 August 2014.

- Moir, William H., Jerry F. Franklin, and Chris Maser, "Environment" (PDF), Lost Forest Research Natural Area, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, United States Forest Service, Department of Agriculture, Portland, Oregon, 1973, pp. 6–8.

- "Fossil Lake", interpretive sign, Bureau of Land Management, United States Department of Interior, posted at entrance to Fossil Lake Area of Critical Environmental Concern near Christmas Valley, Oregon, erected prior to 2010.

- Chadwick, Kristen L. and Andris Eglitis, Health Assessment of the Lost Forest Research Natural Area (PDF), Central Oregon Service Center for Insects and Diseases, United States Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Bend, Oregon, February 2007, pp. 1–2.

- McArthur, Lewis A. and Lewis L. McArthur, "Fossil Lake", Oregon Geographic Names (Seventh Edition), Oregon Historical Society Press, Portland, Oregon, 2003, p. 376.

- "Areas of Critical Environmental Concern", Proposed Lakeview Resource Management Plan and Final Environmental Impact Statement, Lakeview District, Bureau of Land Management, United States Department of Interior, Lakeview, Oregon, January 2003, pp. 2.65–2.67.

- Moir, William H., Jerry F. Franklin, and Chris Maser, "History of Disturbance" (PDF), Lost Forest Research Natural Area, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, United States Forest Service, Department of Agriculture, Portland, Oregon, 1973, p. 15.

- J. W. (John Whiteaker), "A Trip to the Fossil Beds", Eugene City Guard, Eugene, Oregon, 29 September 1877, p. 3.

- Mack, Tony, "Thomas Condon: Oregon's Grand Old Fossil Man", Horizons insert, The Bulletin, Bend, Oregon, 26 April 1993, pp. 5–6.

- Brogan, Phil F., East of the Cascades, Binfords and Mort, Portland, Oregon, 1965, pp. 7–8.

- Hatton, Raymond L., High Desert of Central Oregon, Binford and Mort, Caldwell, Idaho, 1977, pp. 126–139.

- "Southern Oregon", The Oregonian, Portland, Oregon, 5 November 1879, p. 1.

- Ashwill, Melvin S., "Paleontology in Oregon: Workers of the Past" (PDF), Oregon Geology, Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, Portland, Oregon, December 1987, pp. 147–149.

- Brogan, Phil F., "Fossil Lake Story Retold", The Sunday Oregonian, Portland, Oregon, 7 March 1954, p. 35.

- Elftman, Hert Oliver, Pleistocene Mammals of Fossil lake, Oregon, American Museum Novitates (Number 481), American Museum of Natural History, New York City, New York, 14 July 1931, pp. 3–5.

- McArthur, Lewis A. and Lewis L. McArthur, "Cliff", Oregon Geographic Names (Seventh Edition), Oregon Historical Society Press, Portland, Oregon, 2003, p. 209.

- Waring, Gerald A., "Christmas Lake Valley" (PDF), Geology and Water Resources of a Portion of South-Central Oregon, Water-Supply Paper 22O, United States Geological Survey, United States Department of Interior, Washington, District of Columbia, 1908, pp. 59–61.

- "Fossil Lake Area Closed to Vehicles Permanently", Eugene Register-Guard, Eugene, Oregon, 9 October 1979, p. B1.

- Liedthe, Kurt, "Fossil Lake Gets More Fossils: Columbian Mammoth Tracks", The Bulletin, Bend, Oregon, 6 March 2018, p.A2.

- Brogan, Phil F., "Wind Whips Fossil bed", The Sunday Oregonian, Portland, Oregon, 17 May 1970, p. RE14.

- "Condon Fossil Collection", Museum of Natural and Cultural History, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon, 5 August 2014.

- "Sand Dunes Road Maintenance and Re-Alignment OR-L050-2009-0063-EA" (PDF), Notice of Availability Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Impact, Lakeview Resource Area, Bureau of land Management, United States Department of Interior, Lakeview, Oregon, 17 August 2009, pp. 6–7.

- Moir, William H., Jerry F. Franklin, and Chris Maser, "Plant Communities" (PDF), Lost Forest Research Natural Area, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, United States Forest Service, Department of Agriculture, Portland, Oregon, 1973, p. 13.

- "Wildlife list for Fossil Lake", Oregon Wildlife Explorer, National Resources Digital Library, Oregon State University Libraries, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, 5 August 2014.

- Moir, William H., Jerry F. Franklin, and Chris Maser, "Fauna" (PDF), Lost Forest Research Natural Area, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, United States Forest Service, Department of Agriculture, Portland, Oregon, 1973, pp. 14–15.

- Ingram, Guy M., "The Little Bear Wonder of Oregon", The Oregon Sportsman (Volume 5, Issue 4), Oregon State Sportsmen's League, Portland, Oregon, October 1917, pp. 275-276

- Jewett, Stanley G., "The So-Called Dwarf Bear of Oregon", The Murrelet (Volume 3), Pacific Northwest Bird and Mammal Society, Seattle, Washington, 1 October 1922, p. 9.

- Kriegh, LeeAnn, "Lava Bear", The Nature of Bend, Tempo Press, Bend, Oregon, 2016, p. 211.

- "Frequently Asked Questions", Des Chutes Historical Museum, Deschutes County Historical Society, Bend, Oregon, accessed 1 August 2016.

External links

- Bureau of Land Management, Lakeview District

- Shine, Gregory P. "Fossil Lake". The Oregon Encyclopedia.