French Grand Prix

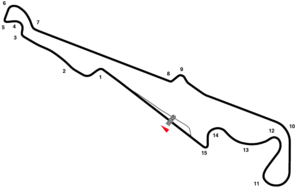

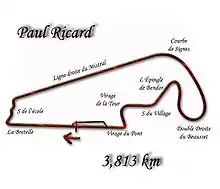

The French Grand Prix (French: Grand Prix de France), formerly known as the Grand Prix de l'ACF, is an auto race held as part of the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile's annual Formula One World Championship. It is one of the oldest motor races in the world as well as the first "Grand Prix". It ceased shortly after its centenary in 2008 with 86 races having been held, due to unfavourable financial circumstances and venues. The race returned to the Formula One calendar in 2018 with Circuit Paul Ricard hosting the race.

| Circuit Paul Ricard (2018–present) | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 87 |

| First held | 1906 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Laps | 53 |

| Last race (2019) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

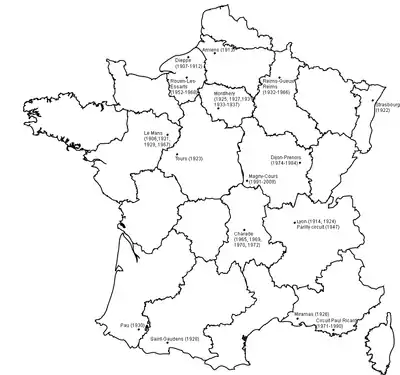

Unusually even for a race of such longevity, the location of the Grand Prix has moved frequently with 16 different venues having been used over its life, a number only eclipsed by the 23 venues used for the Australian Grand Prix since its 1928 start. It is also one of four races (along with the Belgian, Italian and Spanish Grands Prix) to have been held as part of the three distinct Grand Prix championships (World Manufacturers' Championship in the late 1920s, European Championship in the 1930s and Formula One World Championship since 1950).

The Grand Prix de l'ACF was tremendously influential in the early years of Grand Prix racing, leading the establishment of the rules and regulations of racing as well as setting trends in the evolution of racing. The power of the original organiser, the Automobile Club de France, established France as the home of motor racing organisation.

History

Origins

France was one of the first countries to hold motor racing events of any kind. The first competitive motor race, the Paris to Rouen Horseless Carriages Contest was held on 22 July 1894, and was organized by the Automobile Club de France (ACF). The race was 126 km (78 mi) long and was won by Count Jules-Albert de Dion in his De Dion Bouton steam powered car in just under 7 hours. This race was followed by races starting in Paris to various towns and cities around France such as Bordeaux, Marseille, Lyon and Dieppe, and also to various other European cities such as Amsterdam, Berlin, Innsbruck and Vienna. The 1901 Paris-Berlin race was noteworthy as the race winner, Henri Fouriner averaged an astonishing 57 mph (93 km/h) in his Mors, but there were details of other incidents. A competitor driving a 40H.P. Panhard suddenly found the road blocked by a tram in the village of Metternich, and he deliberately ran into the vehicle to avoid the crowd of spectators. The tram was knocked off the rails; the car was hardly damaged. And in Reims, a future location of many French Grands Prix, another competitor hit and killed a child who wandered onto the road with his Mors.

But these races, held on public dirt roads that were not all closed to the public came to a halt in 1903. The Paris-Madrid race, a 1,307 km (812 mi) long competition from the French capital to the Spanish capital held in May of that year had over 300 entrants. Some of the cars were doing 140 km/h (87 mph)- an astonishingly fast speed for the time- not even rail locomotives were capable of hitting these speeds. It was not known at the time how safe these races would be or how these cars- made mostly of wood would perform, and development of the car had improved significantly over 9 years. The race was a disaster, with 8 people killed and over 15 injured in multiple accidents- and all this happened before any of the competitors reached the Spanish border. Crowds of onlookers would stand right on the edge of the track, and children were wandering into the roads which became very dusty and visibility was limited at best. The most notable fatality of this race was one Marcel Renault, one of the 3 brothers who founded Renault. When Renault reached the village of Payré just south of Grand Poitiers he lost control of his 16HP Renault in poor visibility caused by excess dust. The car went into a gutter and crashed into a tree, and Renault sustained a horrific wound in the side of his head and dislocated his shoulder. Fellow competitor Leon Théry stopped his Decauville in order to help Renault and his riding-mechanic Vauthier, still trapped in their car. No doctors were on hand, but Théry found one at the next village and sent him to the place of accident- riding a bicycle to get there. The doctor conveyed back Renault to the nearest hospital in Grand Poitiers, where Renault succumbed to his injuries two days later, while Vauthier survived with minor injuries. Accidents continued throughout the day; cars hit trees and disintegrated, they overturned and caught fire, axles broke and inexperienced drivers crashed on the rough roads. The race was eventually called off by the French government and there was no declared winner. The cars were impounded by the French authorities, towed to the nearest rail stations by horses and transported back to Paris by train. The race created a political uproar in France, and a French magazine did their own investigation into the race. Speed, dust created by the cars, poor organization and lack of crowd control were to blame for these tragedies and even French Prime Minister Émile Combes was held partially responsible because he was the ultimate authority on allowing the race to proceed.

Other races were organized by American newspaper publisher James Gordon Bennett called the Gordon Bennett Cup, 4 of which were in France. 3 city-to-city races in 1900, 1901 and 1902, all starting in Paris were organized by Bennett and they attracted top racers from the United States and Western Europe. But after the 1903 Paris-Madrid race, the French government banned point-to-point car races on open public roads, so Bennett moved the 1903 race to Ireland on a closed circuit 2 months after Paris-Madrid, the first of its kind. This race was won by Belgian Camille Jenatzy in a Mercedes, who was one of the bravest and most fearless racing drivers of his time. The 1904 race was held in western Germany while the last Gordon Bennett Cup race was held in an 137 km (85 mi) circuit in Auvergne in south-central France. The race started in Clermont-Ferrand, and was run over 4 laps, and was won by Théry in a Brasier.

Closed public road courses

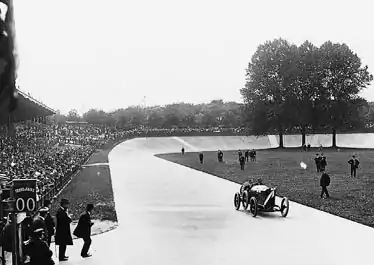

The French Grand Prix, open to international competition was first run on 26 June 1906 under the auspices of the Automobile Club de France in Sarthe with a starting field of 32 automobiles. The Grand Prix name ("Great Prize") referred to the prize of 45,000 French francs to the race winner.[1] The franc was pegged to the gold at 0.290 grams per franc, which meant that the prize was worth 13 kg of gold, or €191,000 adjusted for inflation. The earliest French Grands Prix were held on circuits consisting of public roads near towns through northern and central France, and they usually were held at different towns each year, such as Le Mans, Dieppe, Amiens, Lyon, Strasbourg, and Tours. Dieppe in particular was an extremely dangerous circuit – 9 people (5 drivers, 2 riding mechanics, and 2 spectators) in total were killed at the three French Grands Prix held at the 79 km (49-mile) circuit.

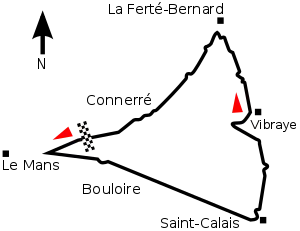

The 1906 race was the first ever race named "Grand Prix"; other, later, international events in the 1900s and 1910s in Europe and the United States had their own names with the term "Prize" in them, such as Grand Prize in America or Kaiserpreis (English: Emperor's Prize) in Germany. The French Grand Prix race was run on a very fast 66-mile (106 km) one-off anti-clockwise closed public road circuit east of the small western French city of Le Mans, starting in the village of Saint-Mars-la-Briere. It then went down the Route D323 and turned a hard left onto Route D357 near the commune of Yvre-l-Eveque onto a 4-mile straight towards the village of La Butte, then down a 15-mile straight through Bouloire and then into a twisty section in Saint-Calais. The circuit then went north on Route D1 through Berfay and then entered a twisty section in a forest before Vibraye and then went north again, entering a series of fast corners in and near Lamnay, and then turned west at La Ferte-Bernard. The circuit then went down Route D323 again and down multiple straights 3 to 6 miles long with a few fast corners at Sceaux-sur-Huisne and Conerre, before returning to the pits at Saint-Mars-la-Briere. Circuits in Europe that went through multiple rural towns like this one became ever more common on public road circuits in France and other European countries. Long straights also became a staple of circuits in France, particularly at future iterations of the relocated Sarthe circuit at Le Mans- a city that would host another race that would become a fixed staple in motor racing circles. The Hungarian Ferenc Szisz won this very long 12‑hour race on a Renault from Italian Felice Nazzaro in a Fiat, where laps on this circuit took just under an hour and the horse carriage road surface was made of dirt; even so this did not stop the fastest lap average speed at being 73.37 mph (118.09 km/h)- an astonishingly fast speed for the time. The 1908 race saw Mercedes humiliating the French organizers and finishing 1-2-3 at the lethal circuit at Dieppe, where no less than 4 people were killed during the weekend. The 1913 race was won by Georges Boillot on a one-off 19-mile (31 km) circuit near Amiens in northern France. Amiens was another deadly circuit – it had a 7.1 mile straight and 5 people were killed during its use during pre-race testing and the race weekend itself.

The 1914 race, run on a 23‑mile circuit near Lyon is perhaps the most legendary and dramatic Grand Prix of the pre‑WWI racing era. This circuit had a twisty and demanding section down to the town of Le Madeline and then an 8.3 mile straight which returned to the pits. This race was a hard-fought battle between the French Peugeots and the German Mercedes. Although the Peugeots were fast and Boillot ended up leading for 12 of the 20 laps after Max Sailer in a Mercedes unexpectedly dropped out with engine failure on Lap 6, the Dunlop tyres they used wore out badly compared to the Continentials that the Mercedes cars were using. Boillot's four-minute lead was wiped out by Christian Lautenschlager in a Mercedes while Boillot stopped an incredible eight times for tyres. Although Boillot drove very hard to try to catch Lautenschlager, he had to retire on the last lap due to engine failure, and for the second time in 6 years Mercedes finished 1–2–3; a humiliating result for the organizers and Peugeot.

Thanks to World War I and the amount of damage it did to France, the Grand Prix was not brought back until 1921, and that race was won by American Jimmy Murphy with a Duesenberg at the Sarthe circuit at Le Mans, which was the now legendary circuit's first year of operation. Bugatti made its debut at the 1922 race at an 8.3‑mile (13 km) off-public road circuit near Strasbourg near the French-German border – which was very close to Bugatti's headquarters in Molsheim. It rained, and the muddy circuit was in a dreadful condition. This race became a duel between Bugatti and Fiat – and Felice Nazzaro won in a Fiat, although his nephew and fellow competitor Biagio Nazzaro was killed after the axle on his Fiat broke, threw a wheel and hit a tree; the 32-year old and his riding mechanic both suffered fatal head injuries. The 1923 race at another one-off circuit near Tours featured another new Bugatti – the Type 32. This car was insultingly dubbed the "Tank", owing to its streamlined shape and very short wheelbase. This car was fast on the straights of this high-speed public road circuit – but it handled badly and was outpaced by Briton Henry Segrave in a supercharged Sunbeam, supercharging being common feature of Grand Prix cars during this period. Segrave won the race, and the Sunbeam would be the last British car to win an official Grand Prix until Stirling Moss's victory with a Vanwall at the 1957 British Grand Prix. Segrave, a known teetotaler was given a glass of champagne after his victory, because apparently there wasn't any water available in the pits area. The 1924 race was held again at Lyon, but this time on a shortened 14‑mile variant of the circuit used in 1914. Two of the most successful Grand Prix cars of all time, the Bugatti Type 35 and the Alfa Romeo P2 both made their debuts at this race. The Bugattis, with their advanced alloy wheels suffered tyre failure, and Italian Giuseppe Campari won in his Alfa P2.

France's first permanent circuit and other public road circuits

In 1925, the first permanent autodrome in France was built, it was called Autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry, located 20 miles south of the centre of the French capital of Paris. The 7.7‑mile (12.3 km) circuit included a 51‑degree concrete banking, an asphalt road course and then-modern facilities, including pit garages and grandstands. After the construction of Brooklands in England in 1907, and Indianapolis in the United States in 1908 and after World War I, Monza in Italy was opened in 1922, and Stiges–Terramar in Spain was also opened in 1923. The French were then prompted to construct a purpose-built racing circuit at Montlhéry in the north and then Miramas in the south. Nürburgring in Germany followed in 1927. Montlhery first held the Grand Prix de l'ACF in 1925 as part of the inaugural World Manufacturers' Championship, the first time Grands Prix were grouped together to form a championship. The circuit drew huge crowds and they were witnesses to the spectacular sight of fast cars racing on Montlhéry's steep banking and asphalt road course, which had many fast corners and long straights, and was located in a forest. The first race at Montlhéry was marred by the fatal accident of Antonio Ascari in an Alfa P2. Miramas, a high-banked concrete oval track like Brooklands and part of Montlhéry was completed in 1926, and it played host to the Grand Prix that year. This race saw only three cars compete, all Bugattis, and was won by Frenchman Jules Goux who had also won the Indianapolis 500 in 1913.

The 1927 race at Montlhéry was won by Frenchman Robert Benoist in a Delage. 1929 saw a brief return to Le Mans, which was won by William Grover-Williams in a Bugatti; this was the man who had won the first ever Monaco Grand Prix earlier in the year; Grover-Williams had also won the 1928 race in a Bugatti at the 17-mile (28 km) Saint-Gaudens circuit in the south, not far from Toulouse. The 1930 French Grand Prix, held at Pau back down in the south was one of the more memorable French Grands Prix of the pre-World War II period. This race, held in September on a one-off triangular 9.8‑mile (15.8 -km) public road circuit just a few kilometres away from the current Pau Grand Prix track saw a special supercharged version of the famous Bentley 4½ Litre called the Blower Bentley compete in the race with Briton and "Bentley Boy" Tim Birkin driving. The Bentley team had been dominating the famed 24 Hours of Le Mans, and this Blower Bentley had its headlights and mudguards removed, as these were not needed for this race, giving it the appearance of an open-wheel car. The Bentley, which was much larger and heavier than the small Bugattis around it performed well – at this very fast circuit which was made up of very long straights and tight hairpins actually suited the powerful Blower Bentley, and it enabled Birkin to pass the pits at 130 mph (208 km/h) (very fast for that time), and he overtook car after car – to the amazement of the crowd. But he finished second to Frenchman Philippe Étancelin in a Bugatti.

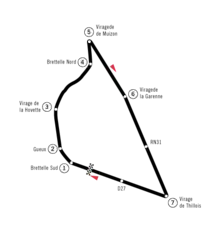

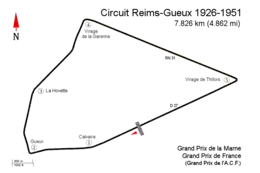

Montlhéry would also be part of the second Grand Prix championship era; the European Championship when it began in 1931. Other public road circuits near towns such as Reims also played host to French Grand Prix, such as the fast, straight and slow corner-dominated 4.8‑mile Reims-Gueux circuit in the Champagne wine region of Northern France 144 km (90 mi) east of Paris for 1932, where Italian legend Tazio Nuvolari won in an Alfa Romeo. But from 1933 to 1937 Montlhéry would become the sole host of the event. The 1934 French Grand Prix marked the return of Mercedes-Benz to Grand Prix racing after 20 years, with an all-new car, team, management, and drivers, headed by Alfred Neubauer. 1934 was the year where the German Silver Arrows debuted (an effort heavily funded by Hitler's Third Reich), with Auto Union having already debuted its powerful mid-engined Type–A car for a race at AVUS in Germany. Although the Monégasque driver Louis Chiron won in an Alfa, the Silver Arrows dominated the race. The high-tech German cars seemed to float over the rough concrete banking at Montlhéry where all the other cars seemed to be visibly affected by the concrete surface. Makeshift chicanes were placed at certain points on the very high-speed circuit in an effort by the French to slow the very fast German cars down for the 1935 race, but this effort came to nothing as Mercedes superstar Rudolf Caracciola won that year's race.

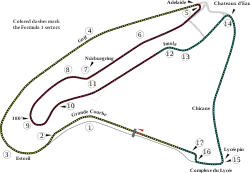

Reims, Rouen and Charade

The French Grand Prix returned to the Reims-Gueux circuit for 1938 and 1939, where the Silver Arrows continued their domination of Grand Prix racing. The Reims-Gueux circuit had its straights widened and facilities updated for the 1938 race. It was around this time that the French Grand Prix had some of its prestige transferred after 2 years of being a sportscar race- the Monaco Grand Prix had gained a huge amount of prestige and would become the premier French-related Grand Prix event, taking place in a tiny principality surrounded by France; but the French Grand Prix was still an important race now held traditionally on the first weekend of July. But when World War II began, the French Grand Prix did not come back until 1947, where it was held at the one-time Parilly circuit near Lyon, a race that was marred by an accident involving Pierre Levegh crashing into and killing 3 spectators. After that, Grand Prix racing returned to Reims-Gueux, where another manufacturer – Alfa Romeo – would dominate the event for 4 years. 1950 was the first year of the Formula One World Championship, but all the Formula One-regulated races were held in Europe. The race was won by Argentine Juan Manuel Fangio, who also won the next year's race – the longest Formula One race ever held in terms of distance covered, totalling 373 miles.

The prestigious French event was held for the first time at the Rouen-Les-Essarts circuit in 1952, where it would be held four more times over the next 16 years. Rouen was a very high speed circuit located in the northern part of the country, that was made up mostly of high speed bends. But the race returned to Reims in 1953, where the triangular circuit, which was originally made up of three long straights (with a few slight kinks) two tight 90 degree right hand corners and a very slow right hand hairpin had been modified to bypass the town of Gueux, making it slightly faster. Reims now had two straights (including the even longer back straight), three very fast bends and two very slow and tight hairpins. This race was a classic, with Fangio in a Maserati and Briton Mike Hawthorn in a Ferrari having a race-long battle for the lead, with Hawthorn taking the checkered flag. 1954 was another special event, and this marked Mercedes's return to top-flight road racing led by Alfred Neubauer, 20 years after their first return to Grand Prix racing – in France. After two wins for the works Maserati team that year at Buenos Aires and Spa, Fangio was now driving for Mercedes and he and teammate Karl Kling effectively dominated the race from start to finish with their advanced W196's. It was not a popular win – Mercedes, a German car manufacturer, had won on French soil – only 9 years after the German occupation of France had ended. The French Grand Prix was cancelled in 1955 because of the Le Mans disaster, and Mercedes withdrew from all racing at the end of that year. The race continued to be held at Reims in 1956, another spell at a lengthened Rouen-Les-Essarts in 1957 and back to Reims again from 1958 to 1961, 1963 and one last event in 1966 at this circuit, located where champagne is made. The 1956 race saw a one-off appearance by Bugatti- they entered a new mid-engined Grand Prix car (which was a novelty at the time, and only the second Grand Prix car ever to be designed this way after the 1930s Auto Unions) designed by renowned Italian engineer Colombo and driven by Maurice Trintignant, but the car was underpowered, overweight, and over-complicated, and it proved to be very difficult to drive; it retired early in the race. The 1958 race was marred by the fatal accident of Italian Luigi Musso, driving a works Ferrari, and it was also Fangio's last Formula One race. Hawthorn, who like many other F1 drivers at the time, held Fangio in very high regard; and was about to lap Fangio (driving in an outdated Maserati) on the last lap on the pit straight when he slowed down and let Fangio cross the line before him so the respected Argentine driver could complete the whole race distance. Hawthorn won, and Fangio finished fourth.

Rouen-Les-Essarts hosted the event in 1962 and 1964, and American Dan Gurney won both these events, one in a Porsche and another in a Brabham. In 1965 the race was held at the 5.1 mile Charade Circuit in the hills surrounding Michelin's hometown of Clermont-Ferrand in central France. Unlike the long straights that made up Reims and the fast curves that made up Rouen, Charade was known as a mini-Nürburgring and was twisty, undulating and very demanding. The short Bugatti Circuit at Le Mans held the race in 1967, but the circuit was not liked by the Formula One circus, and it never returned. Rouen-Les-Essarts hosted the event in 1968, and it was a disastrous event; Frenchman Jo Schlesser crashed and was killed at the very fast Six Frères corner in his burning Honda, and Formula One did not return to the public-road circuit. Charade hosted two more events, and then Formula One moved to the newly built, modern Circuit Paul Ricard on the French riviera for 1971. Paul Ricard Circuit, located in Le Castellet, just outside Marseille and not far from Monaco, was a new type of modern facility, much like Montlhéry had been in the 1920s. It had run-off areas, a wide track and ample viewing areas for spectators. Charade hosted the event one last time in 1972; Formula One cars had become too fast for public road circuits; the circuit was littered with rocks and Austrian Helmut Marko was hit in the eye by a rock thrown up from Brazilian Emerson Fittipaldi's Lotus which ended his racing career.

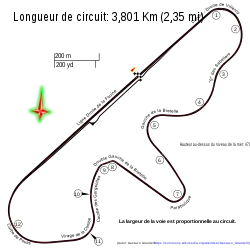

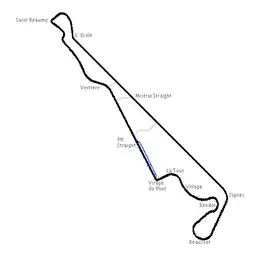

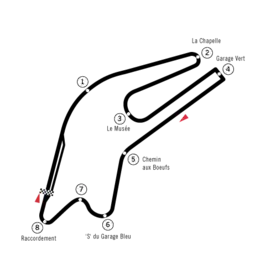

Paul Ricard and Dijon-Prenois

Formula One returned to Paul Ricard in 1973; the French Grand Prix was never run on public road circuits like Reims, Rouen and Charade ever again. Paul Ricard also had a driving school, the École de Pilotage Winfield, run by the Knight brothers and Simon Delatour, that honed the talents of people such as France's first (and so far only) Formula One World Champion Alain Prost, and Grand Prix winners Didier Pironi and Jacques Laffite. The event was run at the new fast, up-and-down Prenois circuit near Dijon in 1974, before returning to Ricard in 1975 and 1976. The race was originally scheduled to be run at Clermont-Ferrand for 1974 and 1975, but the circuit was deemed too dangerous for Formula One. The two venues alternated the venue until 1984, with Ricard getting the race in even-numbered years and Dijon in odd-numbered years (except 1983). 1977 saw a new part of the Dijon circuit built called the "Parabolique". This was done to increase lap times which had been very nearly below a minute in 1974, and the race featured a battle between American Mario Andretti and Briton John Watson; Andretti came out on top to win. Lotus teammates Andretti and Swede Ronnie Peterson dominated the race in 1978 with their dominant 79s, a car that dominated the field in a way not seen since the dominating Alfa Romeo and domineering Ferrari in the early 1950s. The 1979 race was another classic, with the famous end-of-race duel for second place between Frenchman René Arnoux in a 1.5-liter turbocharged V6 Renault and Canadian Gilles Villeneuve in a 3-liter Flat-12 Ferrari. It is considered to be one of the all-time great duels in motorsports, with Arnoux and Villeneuve banging wheels and cars around the fast Dijon circuit before Villeneuve came out on top. The race was won by Arnoux's French teammate Jean-Pierre Jabouille, which was the first race ever won by a Formula One car with a turbo-charged engine. 1980 saw rookie Prost qualify his slower McLaren seventh and Australian Alan Jones beat French Ligier drivers Laffite and Pironi on their home soil, and the 1981 race was the first of 51 victories by future 4-time world champion Prost; driving a Renault, the famed French marque won the next three French Grands Prix. The 1982 event at Ricard was a memorable one for France – it was a turbo-charged engine/French walkover and 4 French drivers finished in the top 4 positions – each of them driving a car with a turbo-charged engine. Renault driver René Arnoux won from his teammate Prost and Ferrari drivers Pironi and Patrick Tambay finished 3rd and 4th. But this French triumph was internally sour: Arnoux violated an agreement that if he was in front of Prost, he would let him by because Prost was better placed in the championship. Much to the chagrin of Prost and the French Renault team's management Arnoux did not do this, despite the management holding out pit boards ordering him to let Prost past. Prost won the next year at the same place, beating out Nelson Piquet in a Brabham with a turbocharged BMW engine; Piquet had led the previous year's race but retired with engine failure.

Dijon was last used in 1984, and by then turbo-charged engines were almost ubiquitous, save the Tyrrell team who were still using the Cosworth V8 engine. The international motorsports governing body at the time, FISA, had instituted a policy of long-term contracts with only one circuit per Grand Prix. The choice was between Dijon and Ricard – the small Prenois circuit had cars lapping in the 1 minute 1 second range, and Ricard was the main testing facility for Formula One at the time. So it was Ricard that was chosen, and it hosted the race from 1985 to 1990. From 1986 onwards Formula One used a shortened version of the circuit, after Elio de Angelis's fatal crash at the fast Verriere bends. De Angelis was not injured by the crash, however his car caught fire and there were no marshals to help him as it was a test session, and he died of smoke inhalation in hospital the next day. These two fast corners and the whole top section of the circuit was not used for the last five races. Prost won the final three races there, the 1988 one being a particularly dramatic win; he overtook his teammate Ayrton Senna at the Curbe de Signes at the end of the ultra fast Mistral Straight and held onto the lead all the way to the finish, and the 1990 (by which time turbo-charged engines had been banned) event was led for more than 60 laps by Italian Ivan Capelli and Brazilian Maurício Gugelmin in underfunded, Adrian Newey designed Leyton-House cars – two cars that had failed to qualify at the previous event in Mexico. Prost, now driving for Ferrari after driving for McLaren from 1984 to 1989, made a late-race charge and passed Capelli to take the victory; Gugelmin had retired earlier.

Magny-Cours

In 1991, the race moved to the Circuit de Nevers Magny-Cours, where it stayed for another 17 years. The move to Magny-Cours was an attempt to stimulate the economy of the area, but many within Formula One complained about the remote nature of the circuit. Highlights of Magny-Cours's time hosting the French Grand Prix include Prost's final of six wins on home soil in 1993, and Michael Schumacher's securing of the 2002 championship after only 11 races. The 2004 and 2005 races were in doubt because of financial problems and the addition of new circuits to the Formula One calendar. These races went ahead as planned, but it still had an uncertain future.

In 2007 it was announced by the FFSA, the race promoter, that the 2008 French Grand Prix was put on an indefinite "pause". This suspension was due to the financial situation of the circuit, known to be disliked by many in F1 due to the circuit's location.[2] Then Bernie Ecclestone confirmed (at the time) that the 2007 French Grand Prix would be the last to be held at Magny-Cours.[3] This turned out not to be true, because funding for the 2008 race was found, and this race at Magny-Cours was the last French Grand Prix for 10 years.

Absence

After various negotiations, the future of the race at Magny-Cours took another turn, with increased speculation that the 2008 French Grand Prix would return, with Ecclestone himself stating "We're going to maybe resurrect it for a year, or something like that".[4] On 24 July, Ecclestone and the French Prime Minister met and agreed to possibly maintain the race at Magny Cours for 2008 and 2009.[5] The change in fortune was completed on July, when the FIA published the 2008 calendar with a 2008 French Grand Prix scheduled at Magny-Cours once again.[6] The 2009 race, however, was again cancelled on 15 October 2008, with the official website citing "economic reasons".[7] A huge makeover of Magny-Cours ("2.0") was planned,[8][9] but cancelled in the end. The race's promoter FFSA then started looking for an alternative host. There were five different proposals for a new circuit: in Rouen with 3 possible layouts: a street circuit, in the dock area, or a permanent circuit near the airport,[10][11] a street circuit located near Disneyland Resort Paris,[12][13] Versailles,[14][15] and in Sarcelles (Val de France),[16] but all were cancelled. A final location in Flins-Les Mureaux, near the Flins Renault Factory was being considered[17] however that was cancelled as well on 1 December 2009.[18] In 2010 and 2011, there was no French Grand Prix on the Formula 1 calendar, although the Circuit Paul Ricard candidated itself for 2012.[19]

10 French drivers have won the French Grand Prix; 7 before World War I and II and 3 during the Formula One championship. French driver Alain Prost won the race six times at three different circuits; however German driver Michael Schumacher has won eight times – the most anybody has ever won any Grand Prix. Monégasque driver Louis Chiron won it five times, and the Argentine driver Juan Manuel Fangio and British driver Nigel Mansell both won four times.

Return to Paul Ricard

In December 2016, it was confirmed that the French Grand Prix would return in 2018 at the Circuit Paul Ricard and it currently holds a contract to host the French Grand Prix until at least 2022.[20][21][22] In an announcement to the nation on 13 April 2020, Emmanuel Macron, the French president, said that restrictions on public events as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic would continue until mid-July, putting the 2020 French Grand Prix, scheduled for 28 June, at risk of postponement.[23] The race was later cancelled with no intention to reschedule for the 2020 championship.[24]

Official names

- 1950, 1952–1954, 1956–1962, 1965: Grand Prix de l'A.C.F. (no official sponsor)[25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34]

- 1951: Grand Prix d'Europe (no official sponsor)[35]

- 1963: Les Grands Prix de Reims (no official sponsor)[36]

- 1964: Le Grand Prix de l'Automobile Club de France (no official sponsor)[37]

- 1966: Grand Prix de l'A.C.F./Grand Prix d'Europe (no official sponsor)[38]

- 1967: Grand Prix de l'A.C.F./Grand Prix de France (no official sponsor)[39]

- 1968–1970, 1972, 1974–1983, 1986–1987, 1994–1997, 2005–2008, 2021: Grand Prix de France (no official sponsor)[40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64]

- 1973: Grand Prix de France de Formule 1 (no official sponsor)[65]

- 1984: Grand Prix de France de F.1 (no official sponsor)[66]

- 1985: Grand Prix de France F.1 (no official sponsor)[67]

- 1988–1993: Rhône-Poulenc Grand Prix de France[68][69][70][71][72][73]

- 1998: Grand Prix Mobil 1 de France[74]

- 1999–2004: Mobil 1 Grand Prix de France[75][76][77][78][79][80]

- 2018–2019: Pirelli Grand Prix de France[81][82][83]

Winners of the French Grand Prix

Repeat winners (drivers)

Drivers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

| Wins | Driver | Years |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | 1994, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2006 | |

| 6 | 1981, 1983, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1993 | |

| 5 | 1931, 1934, 1937, 1947, 1949 | |

| 4 | 1950, 1951, 1954, 1957 | |

| 1986, 1987, 1991, 1992 | ||

| 3 | 1960, 1966, 1967 | |

| 1969, 1971, 1972 | ||

| 2 | 1912, 1913 | |

| 1908, 1914 | ||

| 1907, 1922 | ||

| 1925, 1927 | ||

| 1928, 1929 | ||

| 1924, 1933 | ||

| 1936, 1948 | ||

| 1953, 1958 | ||

| 1962, 1964 | ||

| 1963, 1965 | ||

| 1973, 1974 | ||

| 1975, 1984 | ||

| 1977, 1978 | ||

| 2018, 2019 |

^ Louis Chiron won the 1931 race, but shared the win with Achille Varzi.

^ Juan Manuel Fangio won the 1951 race, but shared the win with Luigi Fagioli.

Repeat winners (constructors)

Teams in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was parto of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

| Wins | Constructor | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | 1952, 1953, 1956, 1958, 1959, 1961, 1968, 1975, 1990, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008 | |

| 8 | 1980, 1986, 1987, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1996, 2003 | |

| 7 | 1963, 1965, 1970, 1973, 1974, 1977, 1978 | |

| 1908, 1914, 1935, 1938, 1954, 2018, 2019 | ||

| 6 | 1926, 1928, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1936 | |

| 1924, 1932, 1934, 1948, 1950, 1951 | ||

| 1906, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1983, 2005 | ||

| 5 | 1976, 1984, 1988, 1989, 2000 | |

| 4 | 1964, 1966, 1967, 1985 | |

| 2 | 1912, 1913 | |

| 1907, 1922 | ||

| 1925, 1927 | ||

| 1947, 1949 | ||

| 1933, 1957 | ||

| 1971, 1972 | ||

| 1994, 1995 |

Repeat winners (engine manufacturers)

Manufacturers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | 1952, 1953, 1956, 1958, 1959, 1961, 1968, 1975, 1990, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008 | |

| 11 | 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1980, 1994 | |

| 1906, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1995, 1996, 2005 | ||

| 8 | 1908, 1914, 1935, 1938, 1954, 2000, 2018, 2019 | |

| 6 | 1926, 1928, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1936 | |

| 1924, 1932, 1934, 1948, 1950, 1951 | ||

| 4 | 1960, 1963, 1964, 1965 | |

| 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989 | ||

| 2 | 1912, 1913 | |

| 1907, 1922 | ||

| 1925, 1927 | ||

| 1947, 1949 | ||

| 1933, 1957 | ||

| 1966, 1967 | ||

| 1985, 2003 |

* Built by Cosworth, funded by Ford.

** Built by Ilmor in 2000, funded by Mercedes.

By year

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

- Two races which can be considered to be French Grand Prix were held in 1949. The race at Saint-Gaudens was organised by the ACF like all other French Grand Prix up to 1967, but was held for Sports Cars, whereas the race at Reims was organised as an alternative, and featured a much stronger grid.

Races sometimes considered to be French Grand Prix

Beginning in the early 1920s, French media represented eight races held in France before 1906 as being Grands Prix de l'Automobile Club de France, leading to the first French Grand Prix being known as the ninth Grand Prix de l'ACF. This was done to give the Grand Prix the appearance of being the world's oldest motor race.[84] The winners of these races, along with their original titles, are listed here.

| Year | Race Title | Driver | Constructor | Location | Report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895 | Paris–Bordeaux–Paris race | Peugeot | Paris-Bordeaux-Paris | Report | |

| 1896 | Paris–Marseille–Paris race | Panhard | Paris-Marseille-Paris | Report | |

| 1898 | Paris–Amsterdam–Paris race | Panhard | Paris-Amsterdam-Paris | Report | |

| 1899 | Tour de France | Panhard | Paris-Paris | Report | |

| 1900 | Paris–Toulouse–Paris race | Mors | Paris-Toulouse-Paris | Report | |

| 1901 | Paris–Berlin race | Mors | Paris-Berlin | Report | |

| 1902 | Paris–Vienna race | Renault | Paris-Vienna | Report | |

| 1903 | Paris–Madrid race | Mors | Paris-Madrid | Report |

References

- Grand Prix century – The Telegraph, 10 June 2006

- ITV-F1.com Archived 11 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine 2008 French Grand Prix "Pause"

- ITV-F1.com Archived 2 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine Ecclestone Confirms Magny Cours Departure

- ITV-F1.com Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine Magny-Cours set for reprieve

- BBC Sport Formula One hope for French Grand Prix

- "FIA reveals 18-race calendar for 2008". formula1.com. 27 July 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- "Grand Prix de France – Formule 1 : 28 juin 2009". Gpfrancef1.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "19 June 2008". Grandprix.com. 19 June 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "automobilsport.comautomobilsport.com 20 June 2008". Automobilsport.com. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "20 June 2008". Motorlegend.com. 20 June 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- grandprix.com 19 June 2008

- "Euro Disney the next venue for French GP?". Asiaone.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Noah Joseph (21 November 2008). "Disney Grand Prix plans shelved". Autoblog.com. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Versailles possible for French GP

- "december 11 2007". Grandprix.com. 11 December 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Sarcelles bidding for a Grand Prix". Grandprix.com. 17 September 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "More details emerge from Flins-Mureaux". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 16 March 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- Noble, Jonathan (1 December 2009). "French GP plans suffer fresh blow". autosport.com. Haymarket Publications. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- "Paul Ricard Confirme sa Candidature pour 2011". Autonewsinfo.com. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Billiotte, Julien (5 December 2016). "Le Grand Prix de France confirmé au Ricard – F1i.com". F1i.com (in French). Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- Benson, Andrew (5 December 2016). "French Grand Prix returns for 2018 after 10-year absence". BBC Sport. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- Editor (1 February 2019). "Race Facts - French Grand Prix". F1Destinations.com. Retrieved 16 May 2019.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Formula 1: French Grand Prix set to be postponed because of the coronavirus crisis". BBC Sport. 13 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Formula 1 plan to start season in Austria as French GP called off". BBC Sport. 27 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "1950 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1952 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1953 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1954 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1956 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1957 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1958 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1959 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1959 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.https://www.progcovers.com/motor/f11961.html

- "1962 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1951 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1963 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1964 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1966 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1967 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1968 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1969 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1970 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1972 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1974 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1975 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1976 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1977 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1978 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1979 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1980 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1981 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1982 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1983 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1986 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1987 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "2008 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "France". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Limited. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- "1973 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1984 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1985 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Pirelli becomes title sponsor of Formula 1 2018 Grand Prix de France". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Limited. 25 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Hodges, David (1967). The French Grand Prix.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to French Grand Prix. |