German Grand Prix

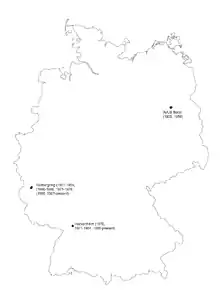

The German Grand Prix (German: Großer Preis von Deutschland) was a motor race that was held most years since 1926, with 75 races having been held. The race has been held at only three venues throughout its history; the Nürburgring in Rhineland-Palatinate, Hockenheimring in Baden-Württemberg and occasionally AVUS in Berlin. The race continued to be known as the German Grand Prix, even through the era when the race was held in West Germany.

| Hockenheimring | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 78 |

| First held | 1926 |

| Last held | 2019 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Circuit length | 4.574[1] km (2.842 mi) |

| Race length | 306.458 km (190.424 mi) |

| Laps | 67 |

| Last race (2019) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

Because West Germany was prevented from taking part in international events in the immediate post-war period, the German Grand Prix only became part of the Formula One World Championship in 1951. It was designated the European Grand Prix four times between 1954 and 1974, when this title was an honorary designation given each year to one Grand Prix race in Europe. It has been organised by the Automobilclub von Deutschland (AvD) since 1926.

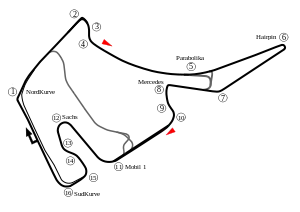

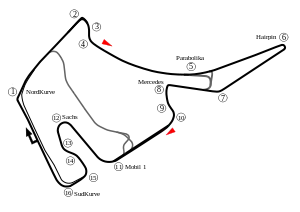

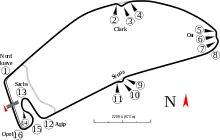

The German Grand Prix was held at Hockenheimring every year between 1977 and 2006 (except 1985). During this time, a separate F1 race was held in Germany at the Nürburgring most years from 1995 until 2007 under the title of the European Grand Prix. Originally intended to begin in 2007, Hockenheimring and the Nürburgring alternated hosting the German Grand Prix between 2008 and 2014, at which point Nürburgring pulled out of hosting the event in 2015, leaving Hockenheim the sole host of the race but only in alternating years until 2018. A further one-year deal placed the German Grand Prix on the 2019 calendar. As of 2020, a race under the name of 'German Grand Prix' has not been run again although Germany hosted the 2020 Eifel Grand Prix.

History

Origins

In 1907, Germany staged the first of the Kaiserpreis races at the 73-mile (118 km) Taunus public road circuit, just outside Frankfurt. The same circuit had been used three years earlier for the 1904 Gordon Bennett Cup race, which was won by Leon Thery in a Brasier, beating Belgian Camille Jenatzy in a Mercedes. Entries were limited to touring cars with engines of less than eight litres. The race itself was a tragedy; a driver and his co-driver were killed 19 miles into the lap and the Taunus circuit was never used again. There was a medical team there, but it took them two and a half hours to get to the site of the accident, of which driver Otto Göbel was badly injured and his co-driver Ludwig Faber, who was pinned under their Adler was already dead. Göbel died of his injuries in hospital later on.[2] Italy's Felice Nazzaro won the race in a Fiat. The Prinz-Heinrich-Fahrt was the biggest German international race which was held from 1908 to 1911 and was organized by Prince Albert Wilhelm Heinrich, These races were point-to-point races which would last a week, would start in Berlin and the competitors had to traverse varying terrains over multiple countries covering around 2,000 km (1,250 mi). Although this kind of racing had been banned in France because of multiple fatal accidents, these races were held with touring cars and the first rallies of any kind and had equal prestige of the Kaiserpreis races before them with drivers such as Nazzaro competing in them.

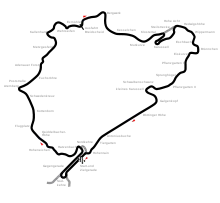

In the early 1920s, ADAC Eifelrennen races were held on the twisty 33.2 km (20.6 mi) Nideggen public road circuit near Cologne and Bonn. Sometime around 1925, the construction of a dedicated race track was proposed just south of the Nideggen circuit around the ancient castle of the town of Nürburg, following the examples of Italy's Monza and Targa Florio courses, and Berlin's AVUS, yet with a different character. The layout of the circuit in the mountains was similar to the Targa Florio event, one of the most important motor races at that time. The original Nürburgring was to be a showcase for German automotive engineering and racing talent. Construction of the track, designed by the Eichler Architekturbüro from Ravensburg (led by architect Gustav Eichler), began in September 1925.

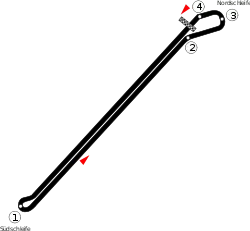

AVUS

The first national event in German Grand Prix motor racing was held at the AVUS (Automobil Verkehrs und Übungs-Straße (Automobile Traffic and Practice Road)) race circuit in southwestern Berlin in 1926 as a sports car race. The AVUS circuit was made up of two 6-mile straights combined with two left-hand hairpins at each end. The first race at AVUS, in heavy rain, was won by Germany's native son, Rudolf Caracciola in a Mercedes-Benz. The event was marred by Adolf Rosenberger's crash into one of the marshals' huts, killing three people. The AVUS circuit was considered extremely dangerous even back then- so the event was moved.[3] The German Grand Prix became an official event in 1929. Although it was raced on in the non-championship AVUS-Rennen in the 1930s which saw some of the fastest road races ever held, the Grand Prix would not return to AVUS until 1959 for a one-off appearance.

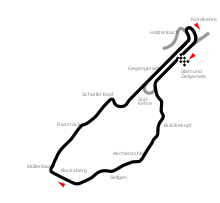

Nürburgring

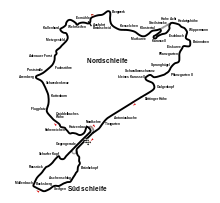

The Grand Prix moved to the new, 28.3 km (17.6 mi) Nürburgring, located in the Eifel Mountain region in western Germany about 70 miles (112 km) from Frankfurt and Cologne. It was inaugurated on 18 June 1927 with the annual race, the ADAC Eifelrennen. This was a huge, incredibly challenging racing circuit that sped and twisted through forests of the Eifel Mountains, and had over 1000 feet (300 m) of elevation change and many spots where the cars visibly left the ground, such as the Flugplatz, Brunnchen and Pflanzgarten sections. There were two more races on the Gesamtstrecke (Combined circuit) combined course, which were both sportscar races, where German pre-war great Rudolf Caracciola would win his second of six German Grands Prix.

The 1930 and 1933 races were cancelled due to economic reasons related to the Great Depression. In 1931, the event began to use only the 14.2-mile (22.8 km) Nordschleife (North Loop), and this would continue onwards throughout the century. Caracciola would win the 1931 and 1932 events in a Mercedes and an Alfa Romeo respectively. Starting in 1934, there were often several races each year with the so-called "Silver Arrows" Grand Prix cars in Germany, e.g. the Eifelrennen, the AVUS race and several hillclimbs. Yet it was only the Grand Prix at the Nürburgring that was the national Grande Epreuve, which counted toward the European Championship from 1935 to 1939. The 1935 event was considered to be one of the greatest motorsports victories of all time. Italian legend Tazio Nuvolari, driving a hopelessly outdated and underpowered Alfa Romeo against state-of-the-art Mercedes and Auto Unions drove a very hard race in appalling conditions. After a dreadful start, he was able to pass a number of cars, particularly while some of the German cars pitted. But after a botched pit stop that cost him six minutes, he drove on the limit, made up that time and was second by the start of the last lap; 35 seconds behind leader Manfred von Brauchitsch in a Mercedes. Von Brauchitsch had ruined his tyres by pushing very hard in the dreadful conditions and Nuvolari was able to catch the German and take victory in front of the stunned German High Command and 350,000 spectators. The small 42-year-old Italian ended up finishing in front of eight running Silver Arrows. Second placed Hans Stuck was two minutes behind Nuvolari.

The 1936 race was won by German driver Bernd Rosemeyer, driving an Auto Union, who also won the Eifelrennen event at the Nordschleife in spectacular style, earning the nickname "Fog Master". The 1937 race saw Carraciola win again in a Mercedes and Auto Union driver Ernst Von Delius die after a crash near the Antonius Bridge on the main straight. Von Delius hit the back of Briton Richard Seaman's Mercedes at 250 km/h (154 mph) and he went flying through a bush and into a field. The car then ended up as a wreck on the side of the road next to the main straight. Von Delius suffered a broken leg and other injuries. He was expected to make a full recovery; but died the following night of thrombosis and other complications. Seaman crashed into a kilometre post and suffered minor injuries; but he survived.[4] The Briton would come back to the Nürburgring to win the 1938 race, also in a Mercedes, which was to be his only championship Grand Prix victory. In 1939 a new track was built near Dresden, called the Deutschlandring, which was intended to host the 1940 German Grand Prix. However, because of the outbreak of World War II, the race was never run and the circuit never utilised for competition. In the same year, Caracciola took his sixth German Grand Prix victory. Soon afterwards Germany was at war and the Grand Prix did not return to international status until 1951.

Nürburgring and the World Championship

x.JPG.webp)

After World War II, Germany had been separated into Eastern and Western territories, and West Germany was banned from international sporting events until 1951. A non-championship Formula 2 race was won by Alberto Ascari in 1950 at the Nürburgring.[5] The German Grand Prix was included as part of the new Formula One championship in its second season. The Nordschleife was to be the mainstay of West Germany's premier motor racing event for the next quarter of a century, and was to be known as the toughest and most technically challenging circuit on the F1 calendar. The expanse of the circuit allowed an average of 375,000 spectators each year to watch the very popular event.[6] The 1951 race was one where Argentine Juan Manuel Fangio led for 14 laps; but he had to refuel his Alfa and he only had third and fourth gears left. While in the pits, he was overtaken by Ascari in a Ferrari and went on to finish second behind the Italian. Fangio won for the first time in 1954 in a Mercedes; the first time a factory Mercedes Grand Prix car had been taken part in 15 years. He won driving the new open-wheeled W196, built at Fangio's request. This event also saw the death of Argentine driver Onofre Marimón in a Maserati 250F during practice. Due to lack of knowledge of the circuit, crucial to doing well at the Nürburgring, he failed to negotiate a tricky bend near the Adenauer Bridge. He went off the road, ploughed through a hedge and down a steep slope, and the car sheared off a tree and tumbled down the slope. Once it came to a stop, Marimón was pinned underneath the 670 kg (1,480 lb) 250F, cars in those days had no roll-over bars to prevent the car from pinning and crushing the driver in the event of an accident; this is what happened to Marimón. The hapless Argentine's injuries were bad enough to kill him a few minutes after the incident. His compatriot and devastated friend Fangio went to check the wreckage of the Maserati; he found it in fourth gear of four; this corner was normally taken in an F1 car in third gear. This proved the accident to be unfortunately of driver error. The 1955 event was cancelled in the aftermath of the Le Mans disaster; all auto racing in Germany (and much of Europe) was banned until the tracks could be upgraded. Fangio would win the next two events.

The 1957 event saw a number of changes. It included a Formula 2 race which was run concurrently alongside the Formula One cars. The track had been resurfaced and the concrete road surface (which was in very bad shape) which made up the pit straight, the Sudkurve and the straight behind the pits was taken out and replaced with tarmac. The 1957 event is, like Nuvolari's 1935 victory, one of the greatest motorsports victories of all time. Fangio led for the beginning of the race in front of two Ferraris driven by Britons Mike Hawthorn and Peter Collins. Fangio planned to refuel during mid-distance; and he did. The pit stop was expected to take 30 seconds. It was a botched one and it took 78 seconds. Fangio was now nearly a minute behind Hawthorn and Collins. He began a charge where he made up several seconds on each lap. He tore huge chunks out of the lap record, breaking it nine times. On the 21st lap (the second-to-last lap) he passed Collins behind the pits, then Hawthorn late into the same lap. The 46-year-old Argentine won the race (his 24th and final F1 victory) and his fifth and final championship. 1958 saw the distance shortened to 15 laps; Briton Tony Brooks won driving a Vanwall VW5. Vanwall was the first British constructor to win a German Grand Prix. Collins crashed into a ditch next to the track at Pflanzgarten, and was thrown out of his car and hit a tree head first. He received severe head injuries and eventually died in a hospital near the circuit.

1959 saw the race go to the ultra-fast AVUS circuit in Berlin. This was the only Formula One race that took place there and was won by Brooks in a Ferrari. The AVUS circuit was now made up of two 2.5-mile straights, a tight left-handed hairpin at one end and a huge 43° brick banking constructed in 1937 on the other end, which was known as Die Mauer des Todes (English: "The Wall of Death").[7] The straights could only go as far as 2.5 miles because if they went any further, the circuit would cross into East Germany. Frenchman and prominent Formula One driver Jean Behra was killed during a support sportscar race driving a Porsche. He lost control and the Porsche went up and flew off the banking there, which had no safety wall or barrier of any kind. Behra was thrown 300 feet from his car and his head struck a flagpole; killing him instantly. Behra had been fired by Ferrari after an altercation in a restaurant in Reims with the Scuderia's manager shortly before his death.

.jpg.webp)

For 1960 the race was moved back to the Nürburgring, but this time on the smaller 4.7-mile (7.7 km) Südschleife (South Loop) section. The race was held for Formula 2 rather than Formula 1, causing the race to lose its championship status, but giving the German spectators what they had missed since 1954, as Porsche had strong new cars built to the 1.5 litre regulations which were to become Formula 1 from 1961. Running the shorter circuit, and lower class, had the benefit of lowering costs in policing and starting money for the organisers.[8][9]

For the rest of the 1960s saw nine Formula One events take place at the Nordschleife. The 1961 event was won by Briton Stirling Moss driving a privately entered Lotus. Moss was able to hold off the two powerful and faster Ferraris of American Phil Hill and German Wolfgang Von Trips. A clever tyre choice and skilful driving in wet weather conditions helped Moss to finish 16 seconds in front of Von Trips. The 1964 event saw Dutch gentleman driver Carel Godin de Beaufort die during practice after he went off at Bergwerk corner. His orange Porsche went through bushes, down an embankment and then hit a tree. He died from his injuries in a hospital near the circuit. Briton John Surtees won for the second year in a row from Jim Clark. In 1965 Clark won, his seventh Formula One victory of that season and won his second Drivers' Championship in a Lotus. 1966 saw changeable weather conditions and a battle between Australian Jack Brabham and Surtees with Brabham taking victory. Briton John Taylor was killed after he hit the back of Belgian Jacky Ickx's Formula 2 Matra MS5 near the bridge at Quddlebacher and Flugplatz. Taylor crashed and his Brabham BT11 caught fire. He received severe burns, from which he succumbed to a month later.

In 1967 a chicane was added before the pits but the cars were already matching 1965 lap times. The 1968 event was yet the scene of another great victory. This event took place in heavy rain and fog. Briton Jackie Stewart won the race by more than four minutes from Graham Hill; he was 30 seconds ahead of the second placed Hill by the end of the first lap. Stewart held the lead amid a driving rainstorm and thick fog.

Jacky Ickx won in 1969 driving a Brabham. The Belgian had made a bad start, clawed back through the field and after a long battle with Stewart, Ickx took the lead from Stewart on Lap 5. The Scot fell back with gearbox problems, leaving the Belgian in a dominant position. Stewart was able to hold on to second place, nearly a minute behind. German driver Gerhard Mitter was killed during practice driving a BMW 269 Formula 2 car after his rear suspension failed and the car went straight on at the downhill section near the very fast Schwedenkreuz bend. This was the fifth Formula One-related fatality at the 14.2-mile German circuit in 15 years, the most out of all the circuits yet used for the championship.

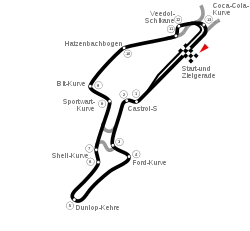

1970 however was to start the demise of the Nordschleife for international motor racing. After the death of Piers Courage at the Dutch Grand Prix a few months previously, the Grand Prix Drivers' Association had a meeting at a hotel in London. Despite considerable pressure from outside parties they voted not to race at the notorious German circuit unless significant changes were made to the track safety conditions of the Nürburgring. Speeds of Formula One cars had increased dramatically as had the technology- the cars were lapping the 'Ring more than 2 minutes faster than they had in 1951, and it had become clear that the Nürburgring, which was essentially a rough, unprotected road that went through forests and valleys situated in an expansive mountain range, was too dangerous and outdated for Grand Prix racing. The changes demanded by the drivers were refused by the circuit owners and organizers and could not possibly be made in time for the 1970 event, forcing a hasty switch to the fast Hockenheimring, which had already been upgraded with safety features. The race itself proved to be an exciting one, as it was won by Austrian Jochen Rindt, resisting a charging Ickx in a Ferrari.

.JPG.webp)

1971 saw the race return to a modified Nürburgring. It was made smoother, straighter and was fitted with Armco barriers and run-off areas wherever possible. But with the layout being virtually the same as before, the circuit retained much of the character that led Stewart to call it "The Green Hell." It was less dangerous than it had been before, but the 'Ring was still by far the most technically challenging circuit on the F1 calendar. It was still dangerously rough and narrow in many areas, and even though some of the worst bumps, jumps and windy straights (particularly at Brunnchen and the Adenauer Bridge) had been smoothed over or made straight, there were still some big jumps on the track, particularly at Flugplatz and Pflanzgarten. Also, there were still some parts of the track that did not have Armco, but more of this was added through the years. The first event on the rebuilt Nordschleife saw Stewart win from his teammate François Cevert, who battled the Swiss Clay Regazzoni for 2nd with for nearly a quarter of the race. The 1972 event saw Jacky Ickx dominate in his Ferrari and Stewart crashed on the last lap after tangling with Regazzoni. The 1973 race was dominated by Tyrrell teammates Stewart and Cevert; and it was to be the 27th and last victory of Stewart's illustrious career. 1974 saw New Zealander Howden Ganley crash heavily at Hatzenbach, seriously injuring the Kiwi. Ganley had already crashed heavily at the Nürburgring the year before and he decided to end his F1 career after his 1974 accident. The race saw Regazzoni win after Austrian Niki Lauda (who had crashed and had broken his wrist at the previous year's German Grand Prix) and South African Jody Scheckter tangled on the first lap; Lauda was out but Scheckter went on to finish second. Briton and multiple motorcycle world champion Mike Hailwood crashed heavily in a McLaren at Pflanzgarten and broke his leg, his auto racing career was effectively ended by this crash. 1975 saw Lauda become the only driver ever to lap the old Nürburgring in under seven minutes; the Austrian lapped the monstrous circuit in his Ferrari in 6 minutes, 58.6 seconds at an average speed of 122 mph (196 km/h), which was good enough for pole position. But like so many years gone by, the weekend saw yet another serious accident. Briton Ian Ashley crashed his Williams FW during practice at Pflanzgarten and he was seriously injured; he did not race in Formula One again for at least two years. Argentine Carlos Reutemann took victory after keeping the lead for five remaining laps while Lauda had a puncture after leading for the first nine laps. Briton Tom Pryce ran as high as second after starting 17th in an under-funded Shadow, but he finished fourth after very hot fuel began to leak into his cockpit. Frenchman Jacques Laffite and Lauda passed Pryce. Laffite finished second which was a milestone for Briton Frank Williams's struggling team; it was the English Williams's first real taste of success in Formula One. Pryce received a medal for his efforts. The 1975 Grand Prix was the fastest race ever run on the old Nürburgring; Lauda's teammate Clay Regazzoni posted the fastest lap at 7:06.4- which was to be the lap record of the old circuit.

Over the years, the Nürburgring was modified several times at the behest of the drivers. However, the 1976 event was one that was to go down in history. Lauda, the reigning world champion, was dissatisfied with the safety arrangements of the mammoth circuit and attempted to organise a boycott the race during a meeting at the third race of the season in Long Beach, California in the United States.[10] Formula One in the 1970s was the beginning towards a safer kind of motor racing and the Nürburgring was considered to be something of an anachronism at that time. However, by its very nature, the Nürburgring was almost impossible to be made safe in its old configuration. It did not have enough marshals and medical support to ensure the circuit's safety- it needed five to six times the marshals and medical staff that a typical F1 race needed at the time, but Huschke von Hanstein and the German organizers were unwilling and possibly unable to provide them- it was extremely expensive; and the spectators viewing the race in the countryside would get into the track for free. In addition to the considerable expense of providing adequate support to the drivers, its geography made the modifications demanded by both the drivers and FIA also prohibitively expensive. There were several parts that were nearly inaccessible to the marshals- there were a number of places where run-off areas could not be built because they were not flat enough, there were parts that were too narrow because there was a cliff face on one side and a drop-off on another, etc. However, the Nürburgring's organizers had a three-year contract with Formula One starting with the 1974 race which included making the track safer. Lauda was outvoted by other drivers because most of them felt that they should complete the contract so as to avoid any legal difficulties; the 1976 race was the last race on that contract. Although the contract included making the circuit safer over those years (and the organizers did that) it had already been decided that the 1976 race would be the last race at the Nordschleife. In addition to safety issues, the increasing commercialisation of Formula One was a factor as well. The extraordinary length of the Nordschleife made it all but impossible for any broadcasting organisation to effectively cover a race there.

As the 1976 race started parts of the circuit were wet and overcast, and other parts were dry and bathed in sunlight, another classic problem of the Nürburgring. After pitting to change from wet to dry tyres at the end of the first lap, Lauda came out again, far behind the leader, West German Jochen Mass. While pushing hard to make up time on the second lap, Lauda crashed at the fast left hand kink before Bergwerk corner over six miles (10.8 km) into the lap, one of the more inaccessible parts of the circuit. Going through the corner, Lauda lost control of his Ferrari when its rear suspension failed. The car crashed into a grass embankment and burst into flames. During the impact, Lauda's helmet was wrenched from his head, and his burning Ferrari was hit by the cars of Brett Lunger, Arturo Merzario and Harald Ertl. Lunger pulled Lauda out of the burning wreckage instead of the ill-equipped track marshals, who only arrived at the scene well after the impact. The resilient Austrian was standing and talking to other drivers right after the accident and his injuries were initially not expected to be serious. However, he had been severely burned and had been breathing in toxic fumes, which damaged his circulatory system. It took the only medical helicopter at the circuit 6 minutes to reach the accident scene from the pits area, as opposed to at most a minute at any other circuit on the Formula One calendar. Lauda later lapsed into a coma and nearly died, putting him out of action for six weeks. The event was red-flagged and restarted; long-time Grand Prix driver Chris Amon elected not to take the restart. This was the last Grand Prix the unlucky New Zealander drove in. Englishman James Hunt won this race, which turned out to be crucial for his championship chances that year. After 49 years of hosting the German Grand Prix the old Nürburgring never hosted a Grand Prix again, and the race returned to Hockenheim.

Hockenheim

The fast, flat Hockenheim circuit near Heidelberg almost played sole host to the German Grand Prix for the next 30 years. The 1977 event was won by Lauda, but was also notable when local driver Hans Heyer competed in the race despite failing to qualify. The 1979 event was one where Swiss Clay Regazzoni in his Williams attempted to chase down his teammate, Australian Alan Jones, but to no avail. 1980 was won by Frenchman Jacques Laffite in a Ligier after Jones dropped to 3rd due to time in the pits changing a punctured tyre, but it was overshadowed by Patrick Depailler's fatal accident at the Ostkurve (which in those days, had no chicane and was flat-out) in testing for Alfa Romeo a few days before the race weekend. The 1981 event saw a tremendous battle between Jones and rising star Alain Prost in a Renault, with Jones passing Prost in the stadium due to interference by Prost's backmarker teammate Rene Arnoux. The race was won by Brazilian Nelson Piquet after Jones pitted with problems with his Williams. The 1982 race saw changes to the circuit; most notably a chicane to the ultra-fast Ost-Kurve and a slower first chicane. It also saw the end of Frenchman Didier Pironi's career; he had an appalling crash in the pouring rain during qualifying. After he hit the back of Prost's Renault, Pironi was launched skyward and then rolled for some time until coming to a stop. Pironi, who was leading the championship at the time, had such serious leg injuries that FIA doctor Sid Watkins nearly had to amputate Pironi's legs in order to get him out of the wrecked Ferrari. The way Formula One cars were designed at the time was in such a way that the drivers sat so far forward in the cockpit that their legs and feet were way in front of the front axle, leaving those human body parts dangerously exposed. They were only protected by only the chassis structure and the aluminium bodywork. During the race, Piquet physically attacked Chilean driver Eliseo Salazar after Salazar punted off the irate Brazilian at the Ostkurve chicane while leading the race. Patrick Tambay won his first race for Ferrari. The 1984 race saw Prost (now driving a McLaren) win and Toleman rookie Ayrton Senna drive very hard at the front of the field during the beginning of the race.

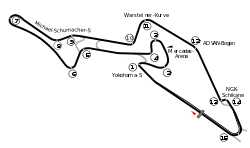

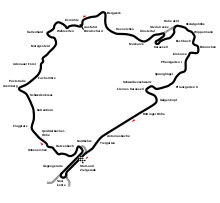

1985 saw a one-off return to the new 2.8-mile (4.5 km) Nürburgring Grand Prix circuit, which had been built upon the site of the old Nordschleife and hosted the European Grand Prix the year before. It was a race where a number of drivers battled for the lead; it was won by Italian Michele Alboreto.

The international motorsports governing body at the time, FISA, had instituted a policy of long-term contracts for one circuit per Grand Prix. The choice for the German Grand Prix was between the new Nürburgring and Hockenheim. It was the latter that was chosen and it stayed there for the next 20 years.[11] The 1986 event was one where a number of the leaders ran on fumes at the very end; top three drivers Piquet, Senna and Prost were all running out of fuel and although Brazilians Piquet and Senna finished 1–2, Prost finished sixth after his car was completely drained of fuel. The 1988 race was run in wet conditions; these conditions were particularly treacherous at Hockenheim because the circuit ran through a forest and the thick moisture from the rain tended to hang in the air because of the trees that surrounded the track. Even when it was not raining, the track still did not dry. Senna (now driving a McLaren) took advantage of his skill in the wet to win over his teammate Prost. The 1989 race was near the height Prost and Senna's famous rivalry and this race was one where the two McLaren teammates drove on their absolute limits throughout the entire race. Prost's gearbox malfunctioned and lost use of sixth gear on the second to last lap and Senna passed him to take the victory. Senna won the next year's race as well from Italian Alessandro Nannini. The 1992 race saw further changes to the Ostkurve after a crash that Érik Comas had there in 1991; it was turned into a more complex chicane rather than simple left-right chicane with a tyre wall in the middle. 1994 saw a further change to the third chicane to make it slower in the aftermath of the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix.

1995 saw German Michael Schumacher win, he was the first German to win his home race since Rudolf Caracciola in 1939. Formula One interest in Germany had peaked during the emergence of Schumacher. 1997 saw an exceptional win by Austrian Gerhard Berger. But the 2000 race was to play host to a number of problems. During the race, a disgruntled ex-Mercedes employee went onto the circuit during the race and disrupted the proceedings; and Jean Alesi had a huge accident at the third chicane and suffered dizziness for three days. And on the far side of the circuit (where the Ost-Kurve was) it was dry, but in the stadium section and the pits, it was pouring with rain. Rubens Barrichello won the race from 18th on the grid, which was his first Formula One victory. 2001 saw a huge accident at the start between Brazilian Luciano Burti in a Prost and Schumacher in a Ferrari; this race was won by Michael's brother Ralf in a BMW-powered Williams.

2002 saw the Hockenheimring dramatically shortened and the layout altered. The forest straights were removed and more corners were added to increase the technical challenge of the circuit. The circuit went from 4.2 to 2.7 miles long. Michael Schumacher won in that year. 2003 was the year Colombian Juan Pablo Montoya won for Williams-BMW, it was the second German GP victory in three years for engines of the Bavarian car maker. That year also saw the last appearance of the British Arrows team, who had been involved in Formula One since 1978. 2004 saw Schumacher continue his domination of that season by winning the German Grand Prix and Spaniard Fernando Alonso won the following year in a Renault after his main rival Kimi Räikkönen suffered a hydraulics failure and retired. 2006 saw Renault's experimental mass damper system deemed legal by the race stewards but it was banned by the FIA. Renault did not use the system for the race and it proved to be their downfall as Schumacher won his home race in a Ferrari.

Alternating venues

In 2006 it was announced that from 2007 until 2010, the German Grand Prix would be shared between the Nürburgring GP circuit (former home of the European and Luxembourg Grands Prix) and the Hockenheimring. The former would hold the races in 2007 and 2009 and the latter in 2008 and 2010. However, the name for the 2007 Grand Prix was later changed. While it was originally intended to be the German Grand Prix,[12] owing to a dispute with Hockenheim over the naming rights of the race, the race was eventually held under the title "Großer Preis von Europa" (European Grand Prix).[13] By 2009, the circuits appeared to have resolved their disputes as the Nürburgring race was held under the German Grand Prix title.

The 2010 GP, held in Hockenheim, at one stage appeared to be in jeopardy as the track owners, the city and the state of Baden-Württemberg, were not willing any more to lose money due to the high licensing costs imposed by F1 management. In addition, talks with Bernie Ecclestone were hampered by his Hitler quotes. If the track had been relieved from being the venue, the owners were intending to returning the track back to its former layout. However, on 30 September 2009, it was announced that the circuit had agreed a deal which would keep it on the calendar until 2018, under a new deal which saw the circuit management and FOA sharing the financial burden of hosting the event.[14] This alternating pattern has continued, with Hockenheim hosting the race in even years, and the Nürburgring hosting the race in odd years until 2013.

Biennial race at Hockenheim

The Nürburgring went through a change of ownership during 2014, but the new owners were unable to sign an agreement to continue hosting the race in odd-numbered years.[15][16] The Hockenheimring wasn't able to host the 2015 or 2017 events either and the German Grand Prix was not run.[17][18] Thus the race became a biennial event, returning to the calendar in 2016 and 2018 at Hockenheim.[19][20][21][22]

One more visit to Hockenheim

The deal with Hockenheim to host the German Grand Prix concluded following the 2018 event.[23] As a result, the future of the event was put in doubt.[23] However, a deal was reached in August 2018 to hold one more event at Hockenheim in 2019.[24][25] While the German Grand Prix is not on the Formula One calendar in 2020,[26] a race titled Eifel Grand Prix was at the Nürburgring in October.

Official names and sponsors

- 1951–1953, 1956–1959, 1951–1953, 1962–1967, 1969–1973, 1975–1981, 1986, 2016: Grosser Preis von Deutschland (no official sponsor)[27]

- 1954, 1961, 1968, 1974: Grosser Preis von Europa

- 1982–1983: AvD-Grosser Preis von Deutschland

- 1984–1985: AvD-Großer Preis von Deutschland

- 1987: Mobil Grosser Preis von Deutschland[28]

- 1988: Mobil 1 Grosser Preis von Deutschland[29]

- 1989–1997, 1999–2006: Grosser Mobil 1 Preis von Deutschland[30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46]

- 1998: Großer Mobil 1 Preis von Deutschland[47]

- 2008–2014: Grosser Preis Santander von Deutschland[48][49][50][51][52][53][54]

Winners of the German Grand Prix

Repeat winners (drivers)

Drivers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

| Wins | Driver | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1926, 1928, 1931, 1932, 1937, 1939 | |

| 4 | 1995, 2002, 2004, 2006 | |

| 2008, 2011, 2016, 2018 | ||

| 3 | 1950, 1951, 1952 | |

| 1954, 1956, 1957 | ||

| 1968, 1971, 1973 | ||

| 1981, 1986, 1987 | ||

| 1988, 1989, 1990 | ||

| 2005, 2010, 2012 | ||

| 2 | 1958, 1959 | |

| 1963, 1964 | ||

| 1969, 1972 | ||

| 1991, 1992 | ||

| 1984, 1993 | ||

| 1994, 1997 | ||

Repeat winners (constructors)

Teams in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of a structured championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

| Wins | Constructor | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 22 | 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953, 1956, 1959, 1963, 1964, 1972, 1974, 1977, 1982, 1983, 1985, 1994, 1999, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2010, 2012 | |

| 11 | 1926, 1927, 1928, 1931, 1937, 1938, 1939, 1954, 2014, 2016, 2018 | |

| 9 | 1979, 1986, 1987, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1996, 2001, 2003 | |

| 8 | 1976, 1984, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1998, 2008, 2011 | |

| 5 | 1966, 1967, 1969, 1975, 1981 | |

| 4 | 1961, 1965, 1970, 1978 | |

| 3 | 2009, 2013, 2019 | |

| 2 | 1932, 1935 | |

| 1934, 1936 | ||

| 1971, 1973 | ||

| 1995, 1997 |

Repeat winners (engine manufacturers)

Manufacturers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of a structured championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 22 | 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953, 1956, 1959, 1963, 1964, 1972, 1974, 1977, 1982, 1983, 1985, 1994, 1999, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2010, 2012 | |

| 14 | 1926, 1927, 1928, 1931, 1937, 1938, 1939, 1954, 1998, 2008, 2011, 2014, 2016, 2018 | |

| 11 | 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1973, 1975, 1976, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981 | |

| 9 | 1991, 1992, 1993, 1995, 1996, 1997, 2005, 2009, 2013 | |

| 6 | 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990, 2019 | |

| 2 | 1932, 1935 | |

| 1934, 1936 | ||

| 1961, 1965 | ||

| 1966, 1967 | ||

| 2001, 2003 |

* Built by Ilmor in 1998

** Built by Cosworth

By year

A pink background indicates an event that was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

Both non-Formula One World Championship events post World War II were run to Formula 2 regulations.

A yellow background indicates an event that was part of the pre-war European Championship.

References

Notes

- "Formula 1 Grosser Preis von Deutschland 2018". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Limited. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- The Motorsport Memorial Team, info@motorsportmemorial.org. "Car and truck fatalities by circuit". Motorsport Memorial. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Author Keith Collantine (8 January 2008). "F1 circuits history part 4: 1958-60 · F1 Fanatic". F1fanatic.co.uk. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- The Motorsport Memorial Team, info@motorsportmemorial.org. "Motorsport Memorial". Motorsport Memorial. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- "1950 German Grand Prix Alberto Ascari-Ferrari-Nürburgring". www.etsy.com. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "F1 - 1973 Nürburgring Nordschleife - 1of2". YouTube. 20 September 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- AVUS

- Posthumus, Cyril (1966). The German Grand Prix. p. 104.

- Eves, Edward (1961). "German Grand Prix". Autocourse: Review of International Motorsport (1960: Part Two).

- "BBC Radio 5 live - Double Take, Niki Lauda gives his verdict on Ron Howard's film Rush". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- "The Brands Hatch & Paul Ricard FAQ - Atlas F1 Special Project". Atlasf1.autosport.com. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Official FIA press release. "2007 FIA Formula One championship circuit and lap information, published on February 14, 2007". Official FIA press release. Archived from the original on 4 April 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2007.

- "Nürburgring". Official Homepage of the Nürburgring. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- TopNews (30 September 2009). "F1 at Hockenheim secured until 2018". topnews.in. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- "German GP uncertainty to return for 2017 race". grandprix.com. 17 July 2015.

- "Nürburgring in the dark over German GP plans". GpUpdate.net. 15 January 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- "Hockenheim rules out hosting German GP". GP Update. GP Update. 17 March 2015. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Germany dropped from 2015 calendar". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Limited. 20 March 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "Hockenheim says 'nothing fixed' for 2015". GPUpdate.net. JHED Media BV. 15 January 2015. Archived from the original on 29 October 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- "German Grand Prix F1 race coming back to Hockenheim in 2016". Autoweek. 10 May 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- "FIA confirms 2016 calendar". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Limited. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- Hall, Sam (20 June 2017). "2018 F1 schedule: France, Germany return; Malaysia out". Autoweek. Crain Communications. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019.

- Benson, Andrew (19 July 2018). "German Grand Prix: Sebastian Vettel fears for future of Hockenheim race". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018.

- "Formula 1 announces draft 2019 season calendar". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Limited. 31 August 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "German GP back on 2019 F1 calendar after new deal agreed". Eurosport. 31 August 2018. Archived from the original on 18 November 2019.

- "F1's German GP could return at different venue after 2020 exit". Autosport. 29 August 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "2016 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1987 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1988 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1989 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1990 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1991 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1992 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1993 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1994 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1995 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1996 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1997 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1999 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2000 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2001 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2002 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2003 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2004 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2005 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2006 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1998 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2008 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2009 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2010 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2011 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2012 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2013 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2014 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2018 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "Germany". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Limited. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "2019 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- Benetton held a British license in 1995 and then an Italian license in 1997, the year of its last victory in Germany

Bibliography

- Födisch, Jörg-Thomas; Völker, Bernhard; Behrndt, Michael (2008). Der grosse Preis von Deutschland: alle Rennen seit 1926 (in German). Königswinter: Heel. ISBN 9783868520439.

- Reuss, Eberhard (1997). Grand Prix: 70 Jahre Grosser Preis von Deutschland (in German). Stuttgart: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 3613018365.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to German Grand Prix. |