Fritwell

Fritwell is a village and civil parish about 5 1⁄2 miles (9 km) northwest of Bicester in Oxfordshire. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 736.[1]

| Fritwell | |

|---|---|

St Olave's parish church | |

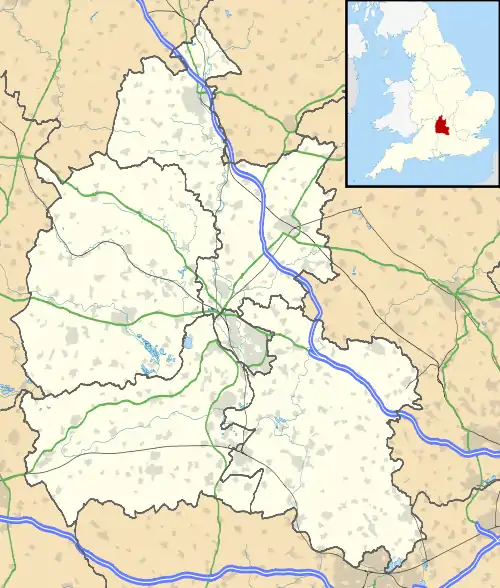

Fritwell Location within Oxfordshire | |

| Population | 736 (2011 Census) |

| OS grid reference | SP5229 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Bicester |

| Postcode district | OX27 |

| Dialling code | 01869 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Oxfordshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Fritwell Parish Council |

The parish's southern boundary is a stream that flows eastwards through Fewcott and past the villages of Fringford and Godington before entering Buckinghamshire where it becomes part of Padbury Brook, a tributary of the Great Ouse. The northeastern boundary of Fritwell parish is the main road between Bicester and Banbury. On other sides the parish is bounded by field boundaries.

The Portway, a road that predates the Roman conquest of Britain, runs north–south parallel with the River Cherwell and passes through the western part of the parish.

The village's toponym is derived from Fyrht-wielle or Fyrht-welle, which is Old English for a wishing well.[2]

Manors

De Lisle

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066 William FitzOsbern, 1st Earl of Hereford held a manor of 10 hides of land at Fritwell. William's son Roger de Breteuil, 2nd Earl of Hereford inherited his estates when William died in 1071, but in 1075 Roger took part in the Revolt of the Earls, was defeated by William I and imprisoned. The Crown confiscated and redistributed Roger's lands and seems to have given Fritwell to Roger de Chesney. The manor descended in the de Chesney family until 1160 by which time Maud, Daughter of William de Chesney, had become married to Henry II's chamberlain Henry FitzGerold. Henry and Maud's son Warin FitzGerold had inherited the manor by 1198 and died in 1216. The manor then passed to Warin's daughter Margaret, who was married to Baldwin de Redvers, son of William de Redvers, 5th Earl of Devon. The manor remained in the de Redvers family until Isabella de Fortibus, Countess of Devon died in 1293. One of the Countess's heirs was Warin de Lisle, a descendant of Margaret de Chesney. Warin's son Robert was created 1st Baron Lisle of Rougemont. In 1368 Robert de Lisle, 3rd Baron Lisle surrendered all his lands to Edward III. From then onwards the tenants of the de Lisle manor were tenants-in-chief.[2]

The de Lisle manor house was probably built late in the 16th century and rebuilt in 1619. Robert Barclay Allardice (1779–1854) lived at the house. The architect Thomas Garner restored the house in 1893 and made it his home[3] until his death in 1906. Sir John Simon (1873–1954) bought the house in 1911, had a west wing added in 1921 and lived there until 1933.[2]

Ormond

In 1086 there was a second manor at Fritwell. It had six hides of land and its feudal overlord was Odo, Bishop of Bayeux. This manor later became known as Ormondescourt. In 1519 Richard Fermor, a merchant, acquired the Ormond manor. Richard remained at his house in Easton Neston and put the Ormond manor in the charge of his younger brother William Fermor who already owned the manor of nearby Somerton. The Ormond manor remained in the Fermor family until the last member of the family, William Fermor of Tusmore Park died in 1828.[2]

The Ormond manor house seems to have been at the southern end of the village. It was still standing when Fritwell was assessed for the hearth tax in 1655 but seems to have been demolished by 1677, when a map of the village was made that showed no trace of it. Dovehouse Farm seems to have been built on its site and incorporating fragments of the old house. A large dovecote was built for it in 1702 and was still standing in 1897. By 1955 the dovecote had gone and the farm had been renamed Lodge Farm.[2]

Churches

Church of England

The earliest known written record of the Church of England parish church of Saint Olave is from 1103.[2] The building was originally Norman, and the north and south doorways and original chancel arch survive from this time. Early in the 13th century the chancel was rebuilt and the bell-tower and south aisle and were added. The chancel retains two Early English Gothic lancet windows from this rebuilding. The Decorated Gothic north aisle was added later in the 13th[3] or early in the 14th century and the Perpendicular Gothic clerestory was added to the nave in the 15th century.[2]

In 1865 the church was restored and the bell tower was rebuilt inder the direction of the Oxford Diocesan architect and Gothic Revivalist G.E. Street. He also had a new, wider chancel arch built and had the original Norman arch relocated against the north wall. In 1868 the square-headed Perpendicular Gothic east window of the chancel was moved to the north aisle and the present east window inserted in its place.[3]

The bell-tower has a ring of four bells. Robert Atton of Buckingham[4] cast the second bell in 1612 and the tenor bell in 1618.[5] G. Mears & Co of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry cast the third bell in 1865[5] and Mears and Stainbank, also of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, cast the treble bell in 1949.[5]

Before 1645 St. Olave's had a turret clock, parts of which still survive.[6]

St. Olave's is now a member of the Benefice of Cherwell Valley along with the parishes of Ardley, Lower Heyford, Somerton, Souldern and Upper Heyford.[7]

Roman Catholic

The Fermors were Roman Catholics and throughout the 18th century they let the Ormond manor to fellow-recusants. Fritwell's Roman Catholic population increased and was served by a priest visiting the village from the Fermor chapel at Tusmore. The Roman Catholic Relief Act was passed in 1791 and a Roman Catholic school had been opened in Fritwell by 1808. However, after 1817 the Catholic population declined and from 1854 no Catholics were recorded until 1897, when Thomas Garner converted to Catholicism and got permission for Mass to be said at the manor house.[2]

Methodist

The parish had a small number of Methodists by 1823, who had their own meeting house by 1829. It is not clear whether this was a private house or a purpose-built chapel, but there was certainly a stone-built chapel by 1853 when the congregation numbered almost 100. The chapel was replaced in 1874 by the present building, which was still in use early in the 20th century but is now a private house.[2][8]

Wesleyan

By 1853 a stone-built chapel for a different branch of Methodism, the Methodist Reform Church, was being completed in Fritwell.[2] In 1857 most Methodist Reform congregations merged with the Wesleyan Association, but the chapel in Fritwell was one of a minority that rejected the merger and together founded the Wesleyan Reform Union instead.

By 1878 non-conformists were said to be a third of the parish's population. A new Wesleyan Reform chapel was built in 1892[3] but thereafter both Methodist congregations decreased. The two chapels merged in 1920and the combined congregation continues today as the Wesleyan Reform Methodist Chapel.[2][8][9]

Economic and social history

A watermill belonging to the parish was recorded in 1235 and again in the 14th century. The parish has no stream large enough to power a mill, so it is likely to have been outside the parish on the River Cherwell. Early in the 19th century the parish had a windmill north of the village near the road linking Fritwell with Souldern. Its site is still called Windmill Ground Field.[2]

An open field system of farming predominated in the parish until the common lands were enclosed in 1808.[2]

The village has a substantial number of 17th-century buildings built from local Cotswold rubblestone.[2]

Clock and watch makers

George Harris (1614–94) was born in Fritwell.[10] He was both a blacksmith and a notable clockmaker who made turret clocks and innovative lantern clocks.[10] Harris repaired the turret clocks at the churches of St Peter ad Vincula, South Newington in 1669 and St. Bartholomew, Yarnton in 1682.[11] In 1671 Sir Anthony Cope, 4th Baronet of Hanwell had Harris make a turret clock for St. Peter's parish church, Hanwell.[12] George Harris's work can now be much sought-after. In 2006 a late 17th-century lantern clock by George Harris was sold in a Bonhams auction for £12,000.[13]

George's third son Nicholas Harris (1657–1738) succeeded to his father's business.[11] Nicholas mended the church clock at St. Peter ad Vincula, South Newington in 1674 and made the clock at St. Mary's parish church, Great Milton in 1699.[11]

Fritwell had further clock and watchmakers in the 18th century: Thomas Jennings (1722–73) and his younger brother William Jennings (1716–80).[11]

Public houses

By 1735 Fritwell had three public houses. These may have been the King's Head and the Wheatsheaf, both of which are 17th-century buildings, and the George and Dragon which is first mentioned by name in a record from 1784. In 1955 all three pubs were still trading but the original George and Dragon had been replaced with a modern building.[2] Both this and the Wheatsheaf have since closed, but the King's Head[14] has since been turned into a home. Cherwell District Council has granted planning permission for the George and Dragon to be demolished and replaced with three houses.[15]

In 1892 a Temperance Hall was built[2] in opposition to the village's pubs.

Parish school

Attempts at education in the parish were intermittent until about 1833, by which time a village school was being held for 30 children. By the 1850s it was being held in the vicarage and in 1871 it had 67 children. A purpose-built school building and schoolmistress's house were completed in 1872 and opened as a National School with two teachers and 64 pupils. Attendance grew to 87 in 1893 and 117 in 1937, and in 1930 an extra classroom was built.[2] In 1948 it was reorganised as a junior school and by 1953 it was a voluntary controlled school. In 1954 the number of pupils had fallen to 77 but it remains open as Fritwell Church of England Primary School.[2][16]

Transport history

The main road between Bicester and Banbury was made into a turnpike by an Act of Parliament passed in 1791.[17] The section through Fritwell parish between Bicester and Aynho ceased to be a turnpike in 1877.[17] When Britain's principal roads were classified early in the 1920s, the stretch of the former turnpike between Bicester and Twyford, Oxfordshire was made part of the A41. In 1990 the section of the M40 motorway between Wheatley, Oxfordshire and Hockley Heath was built and the Bicester — Twyford stretch of the A41 was reclassified as part of the B4100. The M40 runs through the northeastern part of Fritwell parish, passing within 400 yards (370 m) of the village.

In 1907 the Great Western Railway changed the name of the nearest station on the Oxford and Rugby Railway from "Somerton" to "Fritwell & Somerton", despite the fact that the station was in Somerton village about 2 miles (3 km) from Fritwell. The name change was to avoid confusion with another station that the GWR had just opened at Somerton in Somerset.

In 1910 the GWR completed a new main line linking Ashendon Junction and Aynho Junction to shorten the high-speed route between its termini at London Paddington and Birmingham Snow Hill. The line passes through the southwestern part of Fritwell parish and descends into the Cherwell valley via the 1,155 yards (1,056 m) long[18] Ardley Tunnel. The tunnel's southeastern portal is in Fritwell parish, close to where the tunnel passes under the Portway. The railway is now part of the Chiltern Main Line.

References

- "Area: Fritwell (Parish): Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- Lobel 1959, pp. 134–146

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 608–609.

- Dovemaster (25 June 2010). "Founders". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Central Council for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- Davies, Peter (16 December 2006). "Fritewell S Olave". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Central Council for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- Beeson 1989, p. 21.

- Archbishops' Council. "Benefice of Cherwell Valley". A Church Near You. Church of England. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- "Fritwell". Oxfordshire Churches & Chapels. Brian Curtis. Archived from the original on 9 December 2009.

- "Fritwell Wesleyan Reform". Circuits and Churches. The Wesleyan Reform Union.

- Beeson 1989, p. 108.

- Beeson 1989, p. 109.

- Beeson 1989, p. 39.

- "Lot No: 102 A fine and rare late 17th century lantern clock with barrel winding". Sale 14227 - Fine Clocks, 13 Jun 2006 New Bond Street. Bonhams. 13 June 2006. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- The Kings Head Fritwell

- "Plans for George and Dragon Site Approved". Fritwell Parish Council. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- Fritwell Church of Englande Primary School

- "Turnpike Roads in England". Turnpike Trusts in England & Wales. Alan Rosevear.

- "page 1". Railway Tunnel Lengths. David Eaves. 14 May 2015.

Sources

- Beeson, C.F.C. (1989) [1962]. Simcock, A.V (ed.). Clockmaking in Oxfordshire 1400–1850 (3rd ed.). Oxford: Museum of the History of Science. p. 21. ISBN 0-903364-06-9.

- Lobel, Mary D, ed. (1959). A History of the County of Oxford. Victoria County History. 6: Ploughley Hundred. London: Oxford University Press for the Institute of Historical Research. pp. 134–146.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 608–609. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.