Compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to sterilize a specific group of people. Several countries implemented sterilization programs in the early 20th century.[1] Although such programs have been made illegal in most countries of the world, instances of forced or coerced sterilizations persist.

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

| Intersex topics |

|---|

|

Rationalizations for compulsory sterilization include: population size control, gender discrimination, limiting the spread of HIV,[2] "gender-normalizing" surgeries for intersex people, and ethnic genocide (according to the Statute of Rome). In some countries, transgender individuals are required to undergo sterilization before gaining legal recognition of their gender, a practice that the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment has described as a violation of the Yogyakarta Principles.[3]

Affected populations

Governmental family planning programs emerged in the late nineteenth century and have continued to progress through the twenty-first century. During this time, feminists began advocating for reproductive choice, but eugenicists and hygienists were advocating for low income and disabled peoples to be sterilized or have their fertility tightly regulated in order to clean or perfect nations.[4][5] The second half of the twentieth century saw national governments uptake of neo-Malthusian ideology that directly linked population growth to increased (and uncontrollable) poverty, which during the embrace of capitalism, meant that countries were unable to economically develop due to this poverty. Any type of birth control can count as a method of population control if once administered women have no control over its use. These contraceptive methods include sterilization, Depo-Provera, Norplant, and IUDs. Much of these governmental population control programs were focused on using sterilization as the main avenue to reduce high birth rates, even though public acknowledgement that sterilization made an impact on the population levels of the developing world is still widely lacking.[6] Early population programs of the twentieth century were marked as part of the eugenics movement, with Nazi Germany's programs providing the most well-known examples of sterilization of disabled people, paired with encouraging white Germans who fit the "Aryan race" phenotype to rapidly reproduce.[7] In the 1970s, population control programs focused on the "third world" to help curtail over population of poverty areas that were beginning to "develop" (Duden 1992).

In May 2014, the World Health Organization, OHCHR, UN Women, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNFPA and UNICEF issued a joint statement on Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization, An interagency statement. The report references the involuntary sterilization of a number of specific population groups. They include:

- Women, especially in relation to coercive population control policies, and particularly including women living with HIV, indigenous and ethnic minority girls and women. Indigenous and ethnic minority women often face "wrongful stereotyping based on gender, race and ethnicity".

- Disabled people, often perceived as asexual. Women with intellectual disabilities are "often treated as if they have no control, or should have no control, over their sexual and reproductive choices". Other rationales include menstrual management for "women who have or are perceived to have difficulties coping with or managing menses, or whose health conditions (such as epilepsy) or behaviour are negatively affected by menses."

- Intersex persons, who "are often subjected to cosmetic and other non-medically indicated surgeries performed on their reproductive organs, without their informed consent or that of their parents, and without taking into consideration the views of the children involved", often as a "sex-normalizing" treatment.

- Transgender persons, "as a prerequisite to receiving gender-affirmative treatment and gender-marker changes".

The report recommends a range of guiding principles for medical treatment, including ensuring patient autonomy in decision-making, ensuring non-discrimination, accountability and access to remedies.[2]

As a part of human population planning

Human population planning is the practice of artificially altering the rate of growth of a human population. Historically, human population planning has been implemented by limiting the population's birth rate, usually by government mandate, and has been undertaken as a response to factors including high or increasing levels of poverty, environmental concerns, religious reasons, and overpopulation. While population planning can involve measures that improve people's lives by giving them greater control of their reproduction, some programs have exposed them to exploitation.[9]

In the 1977 textbook Ecoscience: Population, Resources, Environment, authors Paul and Anne Ehrlich, and John Holdren discuss a variety of means to address human overpopulation, including the possibility of compulsory sterilization.[10] This book received renewed media attention with the appointment of John Holdren as Assistant to the President for Science and Technology, Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, largely from conservative pundits who have published scans of the textbook online.[11] Several forms of compulsory sterilization are mentioned, including: the proposal for vasectomies for men with three or more children in India in the 1960s,[12] sterilizing women after the birth of their second or third child, birth control implants as a form of removable, long-term sterilization, a licensing system allotting a certain number of children per woman,[13] economic and quota systems of having a certain number of children,[14] and adding a sterilant to drinking water or food sources (the authors are clear that no such sterilant exists nor is one in development).[15] The authors state that most of these policies are not in practice, have not been tried, and most will likely "remain unacceptable to most societies."[15]

Holdren stated in his confirmation hearing that he no longer supports the creation of an optimum population by the U.S. government.[16] However, the population control policies suggested in this textbook are indicative of the concerns about overpopulation, also discussed in The Population Bomb a book written by Paul Ehrlich and Anne Ehrlich predicting major societal upheavals due to overpopulation. As this concern about overpopulation gained political, economic, and social currency, attempts to reduce fertility rates, often through compulsory sterilization, were results of this drive to reduce overpopulation.[17] These coercive and abusive population control policies impacted people around the world in different ways, and continue to have social, health, and political consequences, one of which is lasting mistrust in current family planning initiatives by populations who were subjected to coercive policies like forced sterilization.[18] While population control policies have been widely critiqued by women's health movement in the 1980s and 1990s, with the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994 in Cairo initiating a shift from population control to reproductive rights and the contemporary reproductive justice movement.[19][20] However, new forms of population control policies, including coercive sterilization practices are a global issue and a reproductive rights and justice issue.[21]

By country

International law

The Istanbul Convention prohibits forced sterilization in most European countries (Article 39).[22] Widespread or systematic forced sterilization has been recognized as a Crime against Humanity by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court in the explanatory memorandum. This memorandum defines the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court.[23][24] It does not have universal jurisdiction, with the United States, Russia and China among the countries to exclude themselves.[25] Rebecca Lee wrote in the Berkeley Journal of International Law that, as of 2015, twenty-one Council of Europe member states require proof of sterilization in order to change one's legal sex categorization. Lee wrote that requiring sterilization is a human rights violation and LGBTQ-specific international treaties may need to be developed in order to protect LGBTQ human rights.[26]

Bangladesh

Bangladesh has a long running government operated civilian sterilization program as a part of its population control policy, where poor women and men are mainly targeted. The government offers 2000 Bangladeshi Taka (US$24) for the women who are persuaded to undergo tubal ligation and for the men who are persuaded to undergo vasectomy. Women are also offered a sari (a garment worn by women in Indian subcontinent) and men are offered a lungi (a garment for men) to wear for undergoing sterilization. The referrer, who persuades the woman or man to undergo sterilization gets 300 Bangladeshi Taka (US$3.60).[27]

In 1965, the targeted number of sterilizations per month was 600–1000 in contrast to the insertion of 25,000 IUDs, which was increased in 1978 to about 50,000 sterilizations per month on average.[28] A 50% rise in the amount paid to men coincided with a doubling of the number of vasectomies between 1980 and 1981.[29]

One study done in 1977, when incentives were only equivalent to US$1.10 (at that time), indicated that between 40% and 60% of the men chose vasectomy because of the payment, who otherwise did not have any serious urge to get sterilized.[30]

The "Bangladesh Association for Voluntary Sterilization", alone performed 67,000 tubal ligations and vasectomies in its 25 clinics in 1982. The rate of sterilization increased 25 percent each year.[31]

On 16 December 1982, Bangladesh's military ruler Lieutenant General Hussain Muhammad Ershad launched a two-year mass sterilization program for Bangladeshi women and men. About 3,000 women and men were planned to be sterilized on 16 December 1982 (the opening day). Ershad's government trained 1,200 doctors and 25,000 field workers who must conduct two tubal ligations and two vasectomies each month to earn their salaries. And the government wanted to persuade 1.4 million people, both women and men to undergo sterilization within two years.[32] One population control expert called it 'the largest sterilization program in the world'.[33] By January 1983, 40,000 government field workers were employed in Bangladesh's 65,000 villages to persuade women and men to undergo sterilization and to promote usage of birth-control across the country.[31]

Food subsidies under the group feeding program (VGF) were given to only those women with certificates showing that they had undergone tubal ligation.[34]

In the 1977 study, a one-year follow-up of 585 men sterilized at vasectomy camps in Shibpur and Shalna in rural Bangladesh showed that almost half of the men were dissatisfied with their vasectomies.

58% of the men said their ability to work had decreased in the last year. 2–7% of the men said their sexual performance decreases. 30.6% of the Shibpur and 18.9% of the Shalna men experienced severe pain during the vasectomy. The men also said they had not received all of the incentives they had been promised.[30]

According to another study on 5042 women and 264 men who underwent sterilization, complications such as painful urination, shaking chills, fever for at least two days, frequent urination, bleeding from the incision, sore with pus, stitches or skin breaking open, weakness and dizziness arose after the sterilization.

The person's sex, the sponsor and workload in the sterilization center, and the dose of sedatives administered to women were significantly associated with specific postoperative complaints. Five women died during the study, resulting in a death-to-case rate of 9.9/10,000 tubectomies (tubal ligations); four deaths were due to respiratory arrest caused by overuse of sedatives. The death-to-case rate of 9.9/10,000 tubectomies (tubal ligation) in this study is similar to the 10.0 deaths/10,000 cases estimated on the basis of a 1979 follow-up study in an Indian female sterilization camp. The presence of a complaint before the operation was generally a good predictor of postoperative complaints. Centers performing fewer than 200 procedures were associated with more complaints.[35]

According to another study based on 20 sterilization-attributable deaths in Dacca (now Dhaka) and Rajshahi Divisions in Bangladesh, from January 1, 1979 to March 31, 1980, overall, the sterilization-attributable death-to-case rate was 21.3 deaths/100,000 sterilizations. The death rate for vasectomy was 1.6 times higher than that for tubal ligation. Anesthesia overdosage was the leading cause of death following tubal ligation along with tetanus (24%), where intraperitoneal hemorrhage (14%), and infection other than tetanus (5%) was other leading causes of death.

Two women (10%) died from pulmonary embolism after tubal ligation; one (5%) died from each of the following: anaphylaxis from anti-tetanus serum, heat stroke, small bowel obstruction, and aspiration of vomitus. All seven men died from scrotal infections after vasectomy.[36]

According to a second epidemiologic investigation of deaths attributable to sterilization in Bangladesh, where all deaths resulting from sterilizations performed nationwide between September 16, 1980, and April 15, 1981, were investigated and analyzed, nineteen deaths from tubal ligation were attributed to 153,032 sterilizations (both tubal ligation and vasectomy), for an overall death-to-case rate of 12.4 deaths per 100,000 sterilizations. This rate was lower than that (21.3) for sterilizations performed in Dacca (now Dhaka) and Rajshahi Divisions from January 1, 1979, to March 31, 1980, although this difference was not statistically significant. Anesthesia overdosage, tetanus, and hemorrhage (bleeding) were the leading causes of death.[37]

There are reports that often when a woman had to undergo a gastrointestinal surgery, doctors took this opportunity to sterilize her without her knowledge.[38] According to Bangladesh governmental website "National Emergency Service", the 2000 Bangladeshi Taka (US$24) and the sari/lungi given to the persons undergoing sterilizations are their "compensations". Where Bangladesh government also assures the poor people that it will cover all medical expenses if complications arise after the sterilization.[39]

For the women who are persuaded to have IUD inserted into uterus, the government also offers 150 Bangladeshi Taka (US$1.80) after the procedure and 80+80+80=240 Bangladeshi Taka (0.96+0.96+0.96=2.88 USD) in three followups, where the referrer gets 50 Bangladeshi Taka (US$0.60). And for the women who are persuaded to have etonogestrel birth control implant placed under the skin in upper arm, the government offers 150 Bangladeshi Taka (US$1.80) after the procedure and 70+70+70=210 Bangladeshi Taka (0.84+0.84+0.84=2.52 USD) in three followups, where the referrer gets 60 Bangladeshi Taka (US$0.72).[27]

These civilian exploitative sterilization programs are funded by the countries from northern Europe and the United States.[38] World bank is also known to have sponsored these civilian exploitative sterilization programs in Bangladesh. Historically, World Bank is known to have pressured 3rd World governments to implement population control programs.[40]

Bangladesh is the eighth-most populous country in the world, having a population of 163,466,000 As of 12 November 2017, despite being ranked 94th by total area having an area of 147,570 km2.[41] Bangladesh has the highest population density in the world among the countries having at least 10 million people. The capital Dhaka is the 4th most densely populated city in the world, which ranked as the world's 2nd most unlivable city, just behind Damascus, Syria, according to the annual "Liveability Ranking" 2015 by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU).[42][43]

Bangladesh is planning to introduce a sterilization program in its overcrowded Rohingya refugee camps, where nearly a million refugees are fighting for space, after efforts to encourage birth control failed. Since 25 August 2017, more than 600,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled from Rakhine state, Myanmar to neighboring Bangladesh, which is a Muslim majority country, following a military crackdown against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine. Sabura, a Rohingya mother of seven, said her husband believed the couple could support a large family.

"I spoke to my husband about birth control measures. But he is not convinced. He was given two condoms but he did not use them," she said. "My husband said we need more children as we have land and property (in Rakhine). We don't have to worry to feed them."

District family planning authorities have managed to distribute just 549 packets of condoms among the refugees, amid reports they are reluctant to use them. They have asked the government to approve a plan to provide vasectomies for men and tubectomies (tubal ligation) for women in the camps.

One volunteer, Farhana Sultana, said the women she spoke to believed birth control was a sin and others saw it as against the tenets of Islam.

Bangladeshi officials say about 20,000 Rohingya refugee women are pregnant and 600 have given birth since arriving in the country, but this may not be accurate as many births take place without formal medical help.

Every month 250 Bangladeshi people undergo sterilization routinely under the government's sterilization program in the border town of Cox's Bazar, where the Rohingya refugee Muslims have taken shelter.[44][45]

Brazil

During the 1970s–80s, the U.S. government sponsored family planning campaigns in Brazil, although sterilization was illegal at the time there.[46] Dalsgaard[47] examined sterilization practices in Brazil; analyzing the choices of women who opt for this type of reproductive healthcare in order to prevent future pregnancies and so they can accurately plan their families. While many women choose this form of contraception, there are many societal factors that impact this decision, such as poor economic circumstances, low rates of employment, and Catholic religious mandates that stipulate sterilization as less harmful than abortion.[48]

Canada

Two Canadian provinces (Alberta and British Columbia) performed compulsory sterilization programs in the 20th century with eugenic aims. Canadian compulsory sterilization operated via the same overall mechanisms of institutionalization, judgment, and surgery as the American system. However, one notable difference is in the treatment of non-insane criminals. Canadian legislation never allowed for punitive sterilization of inmates.

The Sexual Sterilization Act of Alberta was enacted in 1928 and repealed in 1972. In 1995, Leilani Muir sued the Province of Alberta for forcing her to be sterilized against her will and without her permission in 1959. Since Muir's case, the Alberta government has apologized for the forced sterilization of over 2,800 people. Nearly 850 Albertans who were sterilized under the Sexual Sterilization Act were awarded C$142 million in damages.[49][50]

As recently as 2017, a number of Indigenous women were not permitted to see their newborn babies unless they agreed to sterilization. Over 60 women are involved in a lawsuit in this case.[51][52]

China

See also: One-child policy and Two-child policy

In 1978, Chinese authorities became concerned with the possibility of a baby boom that the country could not handle, and they initialized the one-child policy. In order to effectively deal with the complex issues surrounding childbirth, the Chinese government placed great emphasis on family planning. Because this was such an important matter, the government thought it needed to be standardized, and so to this end laws were introduced in 2002.[53] These laws uphold the basic tenets of what was previously put into practice, outlining the rights of the individuals and outlining what the Chinese government can and cannot do to enforce policy.

However, accusations have been raised from groups such as Amnesty International, who have claimed that practices of compulsory sterilization have been occurring for people who have already reached their one child quota.[53] These practices run contrary to the stated principles of the law, and seem to differ on a local level.

The Chinese government appears to be aware of these discrepancies in policy implementation on a local level. For example, The National Population and Family Planning Commission put forth in a statement that, “Some persons concerned in a few counties and townships of Linyi did commit practices that violated law and infringed upon legitimate rights and interests of citizens while conducting family planning work.” This statement comes in reference to some charges of forced sterilization and abortions in Linyi city of Shandong Province.[54]

The policy requires a "social compensation fee" for those who have more than the legal number of children. According to Forbes editor Heng Shao, critics claims this fee is a toll on the poor but not the rich.[55] But after 2018, the country has allowed parents to give birth to two children.

Xinjiang

Beginning in 2019, reports of forced sterilization in Xinjiang began to surface.[56][57][58] In 2020, public reporting continued to indicate that large-scale compulsory sterilization was being carried out as part of the ongoing Uyghur genocide.[59][60]

According to researcher Adrian Zenz, 80% of all new IUD placements in China in 2018 were performed in Xinjiang, despite the region only constituting 1.8% of China's population.[61][62][60] However, China's National Health Commission state that the figure is 8.7%.[63]

Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic

Czechoslovakia carried out a policy to sterilize some Romani women, starting in 1973. In some cases the sterilization was in exchange for social welfare benefits, and many victims were given written agreements describing what was to be done to them which they were unable to read due to illiteracy.[64] The dissidents of the Charter 77 movement denounced these practices in 1977–78 as a genocide, but they continued through the Velvet Revolution of 1989.[65] A 2005 report by the Czech government's independent ombudsman, Otakar Motejl, identified dozens of cases of coercive sterilization between 1979 and 2001, and called for criminal investigations and possible prosecution against several health care workers and administrators, re Law on Atrocities relevant pre-1990, CR (ChR).[66]

Colombia

The time period of 1964–1970 started Colombia's population policy development, including the foundation of PROFAMILIA and through the Ministry of Health the family planning program promoted the use of IUDs, the Pill, and sterilization as the main avenues for contraception. By 2005, Colombia had one of the world's highest contraceptive usage rates at 76.9%, with female sterilization being the highest percentage of use at just over 30% (second highest is the IUD at around 12% and the pill around 10%)[67] (Measham and Lopez-Escobar 2007). In Colombia during the 1980s, sterilization was the second most popular choice of pregnancy prevention (after the Pill), and public healthcare organizations and funders (USAID, AVSC, IPPF) supported sterilization as a way to decrease abortions rates. While not directly forced into sterilization, women of lower socio-economic standing had significantly less options to afford family planning care as sterilizations were subsidized.[46]

Denmark

Until June 11, 2014, sterilization was requisite for legal sex change in Denmark.[68]

Germany

One of the first acts by Adolf Hitler after the Reichstag Fire Decree and the Enabling Act of 1933 gave him de facto legal dictatorship over the German state was to pass the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring (Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses) in July 1933.[69][70] The law was signed by Hitler himself, and over 200 eugenic courts were created specifically as a result of this law. Under it, all doctors in the Third Reich were required to report any patients of theirs who were deemed intellectually disabled, characterized mentally ill (including schizophrenia and manic depression), epileptic, blind, deaf, or physically deformed, and a steep monetary penalty was imposed for any patients who were not properly reported. Individuals suffering from alcoholism or Huntington's Disease could also be sterilized. The individual's case was then presented in front of a court of Nazi officials and public health officers who would review their medical records, take testimony from friends and colleagues, and eventually decide whether or not to order a sterilization operation performed on the individual, using force if necessary. Though not explicitly covered by the law, 400 mixed-race "Rhineland Bastards" were also sterilized beginning in 1937.[71][72][73] The sterilization program went on until the war started, with about 600,000 people sterilized.[74]

By the end of World War II, over 400,000 individuals were sterilised under the German law and its revisions, most within its first four years of being enacted. When the issue of compulsory sterilisation was brought up at the Nuremberg trials after the war, many Nazis defended their actions on the matter by indicating that it was the United States itself from whom they had taken inspiration. The Nazis had many other eugenics-inspired racial policies, including their "euthanasia" programme in which around 70,000 people institutionalised or suffering from birth defects were killed.[75]

Guatemala

Guatemala is one country that resisted family planning programs, largely due to lack of governmental support, including civil war strife, and strong opposition from both the Catholic Church and Evangelical Christians until 2000, and as such, has the lowest prevalence of contraceptive usage in Latin America. In the 1980s, the archbishop of the country accused USAID of mass sterilizations of women without consent, but a President Reagan backed commission found the allegations to be false.[76]

India

India's state of emergency between 1975 and 1977 included a family planning initiative that began in April 1976 through which the government hoped to lower India's ever increasing population. This program used propaganda and monetary incentives to, some may construe, inveigle citizens to get sterilized.[77] People who agreed to get sterilized would receive land, housing, and money or loans.[78] Because of this program, thousands of men received vasectomies, but due to much opposition and protest, the country switched to targeting women through coercion, withholding welfare or ration card benefits, or bribing them with food and money.[79] Sanjay Gandhi, the son of then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, was largely blamed for what turned out to be a failed program.[80] A strong backlash against any initiative associated with family planning followed the highly controversial program, the effect of which continues into the 21st century.[81] Sterilization policies are still enforced targeting mostly indigenous and lower classed women being taken to “sterilization camps;” the most recent abuse coming to light in the death of 15 women in Chhattisgarh in 2014.[79]

Israel

In the late 2000s, reports in the Israeli media claimed that injections of long-acting contraceptive Depo-Provera had been forced on hundreds of Ethiopian-Jewish immigrants both in transit camps in Ethiopia and after their arrival in Israel. In 2009, feminist NGO Haifa Women's Coalition published a first survey on the story, which was followed up by Israeli Educational Television a few years later. Ethiopian-Jewish women said they were intimidated or tricked into taking the shot every three months. In 2016 Israel's State Comptroller concluded his inquiry into the affair by claiming that injections of Depo-Provera had not been forced on the women by the State of Israel. The Comptroller did not interview the complainants directly.

Japan

In the first part of the reign of Emperor Hirohito, Japanese governments promoted increasing the number of healthy Japanese, while simultaneously decreasing the number of people deemed to have mental retardation, disability, genetic disease and other conditions that led to inferiority in the Japanese gene pool.[82][83]

The Leprosy Prevention laws of 1907, 1931, and 1953 permitted the segregation of patients in sanitariums where forced abortions and sterilization were common and authorized punishment of patients "disturbing peace".[84] Under the colonial Korean Leprosy prevention ordinance, Korean patients were also subjected to hard labor.[85]

The Race Eugenic Protection Law was submitted from 1934 to 1938 to the Diet. After four amendments, this draft was promulgated as a National Eugenic Law in 1940 by the Konoe government.[82] According to Matsubara Yoko, from 1940 to 1945, sterilization was done to 454 Japanese persons under this law. Appx. 800,000 people were surgically processed until 1995.[86]

According to the Eugenic Protection Law (1948), sterilization could be enforced on criminals "with genetic predisposition to commit crime", patients with genetic diseases including mild ones such as total color-blindness, hemophilia, albinism and ichthyosis, and mental affections such as schizophrenia, manic-depression possibly deemed occurrent in their opposition and epilepsy, the sickness of Caesar.[87] The mental sicknesses were added in 1952.

In early 2019, Japan's Supreme Court upheld a requirement that transgender people must have their reproductive organs removed.[88][89]

Peru

In Peru, President Alberto Fujimori (in office from 1990 to 2000) has been accused of genocide and crimes against humanity as a result of the Programa Nacional de Población, a sterilization program put in place by his administration.[90] During his presidency, Fujimori put in place a program of forced sterilizations against indigenous people (mainly the Quechuas and the Aymaras), in the name of a "public health plan", presented on July 28, 1995. The plan was principally financed using funds from USAID (36 million dollars), the Nippon Foundation, and later, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).[91] On September 9, 1995, Fujimori presented a Bill that would revise the "General Law of Population", in order to allow sterilization. Several contraceptive methods were also legalized, all measures that were strongly opposed by the Roman Catholic Church, as well as the Catholic organization Opus Dei. In February 1996, the World Health Organization (WHO) itself congratulated Fujimori on his success in controlling demographic growth.[91]

On February 25, 1998, a representative for USAID testified before the U.S. government's House Committee on International Relations, to address controversy surrounding Peru's program. He indicated that the government of Peru was making important changes to the program, in order to:

- Discontinue their campaigns in tubal ligations and vasectomies.

- Make clear to health workers that there are no provider targets for voluntary surgical contraception or any other method of contraception.

- Implement a comprehensive monitoring program to ensure compliance with family planning norms and informed consent procedures.

- Welcome Ombudsman Office investigations of complaints received and respond to any additional complaints that are submitted as a result of the public request for any additional concerns.

- Implement a 72-hour "waiting period" for people who choose tubal ligation or vasectomy. This waiting period will occur between the second counseling session and surgery.

- Require health facilities to be certified as appropriate for performing surgical contraception as a means to ensure that no operations are done in makeshift or substandard facilities.[92]

In September 2001, Minister of Health Luis Solari launched a special commission into the activities of the voluntary surgical contraception, initiating a parliamentary commission tasked with inquiring into the "irregularities" of the program, and to put it on an acceptable footing. In July 2002, its final report ordered by the Minister of Health revealed that between 1995 and 2000, 331,600 women were sterilized, while 25,590 men submitted to vasectomies.[91] The plan, which had the objective of diminishing the number of births in areas of poverty within Peru, was essentially directed at the indigenous people living in deprived areas (areas often involved in internal conflicts with the Peruvian government, as with the Shining Path guerilla group). Deputy Dora Núñez Dávila made the accusation in September 2003 that 400,000 indigenous people were sterilized during the 1990s. Documents proved that President Fujimori was informed, each month, of the number of sterilizations done, by his former Ministers of Health, Eduardo Yong Motta (1994–96), Marino Costa Bauer (1996–1999) and Alejandro Aguinaga (1999–2000).[91] A study by sociologist Giulia Tamayo León, Nada Personal (in English: Nothing Personal), showed that doctors were required to meet quotas. According to Le Monde diplomatique, "tubal ligation festivals" were organized through program publicity campaigns, held in the pueblos jóvenes (in English: shantytowns). In 1996 there were, according to official statistics, 81,762 tubal ligations performed on women, with a peak being reached the following year, with 109,689 ligatures, then only 25,995 in 1998.[90]

On October 21, 2011, Peru's Attorney General José Bardales decided to reopen an investigation into the cases, which had been halted in 2009 under the statute of limitations, after the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights ruled that President Fujimori's sterilization program involved crimes against humanity, which are not time-limited.[93] It is unclear as to any progress in matter of the execution (debido ejecución sumaria) of the suspect in the course of any proof of their relevant accusations in the legal sphere of the constituted people in vindication of the rights of the people of South America. It may carry a parallel to any suspect cases for international investigation in any other continent, and be in the sphere of medical genocide.

South Africa

In South Africa, there have been multiple reports of HIV-positive women sterilized without their informed consent and sometimes without their knowledge.[94]

Sweden

The eugenistic legislation was enacted in 1934 and was formally abolished in 1976. According to the 2000 governmental report, 21,000 were estimated to have been forcibly sterilized, 6,000 were coerced into a 'voluntary' sterilization while the nature of a further 4,000 cases could not be determined.[95] The Swedish state subsequently paid out damages to victims who contacted the authorities and asked for compensation. Of those sterilized 93% were women.[96]

Compulsory sterilisation did not completely cease until 2012, because in that time transgender individuals were required to undergo it to change legal sex.

Switzerland

In October 1999, Margrith von Felten suggested to the National Council of Switzerland in the form of a general proposal to adopt legal regulations that would enable reparation for persons sterilized against their will. According to the proposal, reparation was to be provided to persons who had undergone the intervention without their consent or who had consented to sterilization under coercion. According to Margrith von Felten:

The history of eugenics in Switzerland remains insufficiently explored. Research programmes are in progress. However, individual studies and facts are already available. For example:

The report of the Institute for the History of Medicine and Public Health "Mental Disability and Sexuality. Legal sterilization in the Vaud Canton between 1928 and 1985" points out that coercive sterilizations took place until the 1980s, it is unclear if the ethnographic impact has been duly investigated and if Hun-descendant French have been affected, as well as prehistoric human descendant communities. The act on coercive sterilizations of the Vaud Canton was the first law of this kind in the European context.

Hans Wolfgang Maier, head of the Psychiatric Clinic in Zurich pointed out in a report from the beginning of the century that 70% to 80% of terminations were linked to sterilization by doctors. In the period from 1929 to 1931, 480 women and 15 men were sterilized in Zurich in connection with termination.

Following agreements between doctors and authorities such as the 1934 "Directive For Surgical Sterilization" of the Medical Association in Basle, eugenic indication to sterilization was recognized as admissible.

A statistical evaluation of the sterilizations performed in the Basle women's hospital between 1920 and 1934 shows a remarkable increase in sterilizations for a psychiatric indication after 1929 and a steep increase in 1934, when a coercive sterilization act came into effect in nearby National Socialist Germany.

A study by the Swiss Nursing School in Zurich, published in 1991, documents that 24 mentally disabled women aged between 17 and 25 years were sterilized between 1980 and 1987. Of these 24 sterilizations, just one took place at the young woman's request.

Having evaluated sources primarily from the 1930s (psychiatric files, official directives, court files, etc.), historians have documented that the requirement for free consent to sterilization was in most of cases not satisfied. Authorities obtained the "consent" required by the law partly by persuasion, and partly by enforcing it through coercion and threats. Thus the recipients of social benefits were threatened with removal of the benefits, women were exposed to a choice between placement in an institution or sterilization, and abortions were permitted only when women simultaneously consented to sterilization.

More than fifty years after ending the National Socialist dictatorship in Germany, in which racial murder, euthanasia and coerced sterilizations belonged to the political programme, it is clear that eugenics, with its idea of "life unworthy of life" and "racial purity" permeated even democratic countries. The idea that a "healthy nation" should be achieved through targeted medical/social measures was designed and politically implemented in many European countries and in the U.S.A in the first half of this century. It is a policy incomparable with the inconceivable horrors of the Nazi rule; yet it is clear that authorities and the medical community were guilty of the methods and measures applied, i.e. coerced sterilizations, prohibitions of marriages and child removals – serious violations of human rights.

Switzerland refused, however, to vote a reparations Act.

United States

The United States During the Progressive era, ca. 1890 to 1920, was the first country to concertedly undertake compulsory sterilization programs for the purpose of eugenics.[97] Thomas C. Leonard, professor at Princeton University, describes American eugenics and sterilization as ultimately rooted in economic arguments and further as a central element of Progressivism alongside wage controls, restricted immigration, and the introduction of pension programs.[98] The heads of the programs were avid proponents of eugenics and frequently argued for their programs which achieved some success nationwide mainly in the first half of the 20th Century.

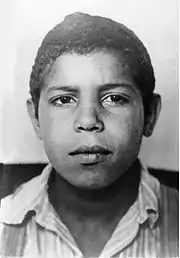

Eugenics had two essential components. First, its advocates accepted as axiomatic that a range of mental and physical handicaps—blindness, deafness, and many forms of mental illness—were largely, if not entirely, hereditary in cause. Second, they assumed that these scientific hypotheses could be used as the basis of social engineering across several policy areas, including family planning, education, and immigration. The most direct policy implications of eugenic thought were that “mental defectives” should not produce children, since they would only replicate these deficiencies, and that such individuals from other countries should be kept out of the polity.[99] The principal targets of the American sterilization programs were the intellectually disabled and the mentally ill, but also targeted under many state laws were the deaf, the blind, people with epilepsy, and the physically deformed. While the claim was that the focus was mainly the mentally ill and disabled, the definition of this during that time was much different than today's. At this time, there were many women that were sent to institutions under the guise of being “feeble-minded" because they were promiscuous or became pregnant while unmarried.

Some sterilizations took place in prisons and other penal institutions, targeting criminality, but they were in the relative minority.[100] In the end, over 65,000 individuals were sterilized in 33 states under state compulsory sterilization programs in the United States, in all likelihood without the perspectives of ethnic minorities.[101]

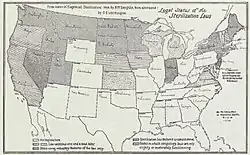

The first state to introduce a compulsory sterilization bill was Michigan, in 1897, but the proposed law failed to pass. Eight years later Pennsylvania's state legislators passed a sterilization bill that was vetoed by the governor. Indiana became the first state to enact sterilization legislation in 1907,[102] followed closely by California and Washington in 1909. Several other states followed, but such legislation remained controversial enough to be defeated in some cases, as in Wyoming in 1934.[103] Sterilization rates across the country were relatively low, with the sole exception of California, until the 1927 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Buck v. Bell which legitimized the forced sterilization of patients at a Virginia home for the intellectually disabled.[104] In the wake of that decision, over 62,000 people in the United States, most of them women, were sterilized.[105] The number of sterilizations performed per year increased until another Supreme Court case, Skinner v. Oklahoma, 1942, complicated the legal situation by ruling against sterilization of criminals if the equal protection clause of the constitution was violated. That is, if sterilization was to be performed, then it could not exempt white-collar criminals.[106]

After World War II, public opinion towards eugenics and sterilization programs became more negative in the light of the connection with the genocidal policies of Nazi Germany, though a significant number of sterilizations continued in a few states through the 1970s. Between 1970 and 1976, Indian Health Services sterilized between 25 and 42 percent of women of reproductive age who came in seeking healthcare services. In addition, the U.S. launched campaigns of sterilization against black women in the South and Latina women in the Southwest in order to break the chain of welfare dependency and curb the population rise of non-white citizens.[107][5] In California, ten women who delivered their children at LAC-USC hospital between 1971-1974 and were sterilized without proper consent sued the hospital in the landmark Madrigal v. Quilligan case in 1975.[108] The plaintiffs lost the case, but numerous changes to the consent process were made following the ruling, such as offering consent forms in the patient's native language, and a 72-hour waiting period between giving consent and undergoing the procedure.[108]

The Oregon Board of Eugenics, later renamed the Board of Social Protection, existed until 1983,[109] with the last forcible sterilization occurring in 1981.[110] The U.S. commonwealth Puerto Rico had a sterilization program as well. Some states continued to have sterilization laws on the books for much longer after that, though they were rarely if ever used. California sterilized more than any other state by a wide margin, and was responsible for over a third of all sterilization operations. Information about the California sterilization program was produced into book form and widely disseminated by eugenicists E.S. Gosney and Paul B. Popenoe, which was said by the government of Adolf Hitler to be of key importance in proving that large-scale compulsory sterilization programs were feasible.[111] In recent years, the governors of many states have made public apologies for their past programs beginning with Virginia and followed by Oregon[109] and California. Few have offered to compensate those sterilized, however, citing that few are likely still living (and would of course have no affected offspring) and that inadequate records remain by which to verify them. At least one compensation case, Poe v. Lynchburg Training School & Hospital (1981), was filed in the courts on the grounds that the sterilization law was unconstitutional. It was rejected because the law was no longer in effect at the time of the filing. However, the petitioners were granted some compensation because the stipulations of the law itself, which required informing the patients about their operations, had not been carried out in many cases. [112] The 27 states where sterilization laws remained on the books (though not all were still in use) in 1956 were: Arizona, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington,[113] West Virginia and Wisconsin.[114] Some states still have forced sterilization laws in effect, such as Washington state.[113]

As of January 2011, discussions were underway regarding compensation for the victims of forced sterilization under the authorization of the Eugenics Board of North Carolina. Governor Bev Perdue formed the NC Justice for Sterilization Victims Foundation in 2010 in order "to provide justice and compensate victims who were forcibly sterilized by the State of North Carolina".[115] In 2013 North Carolina announced that it would spend $10 million beginning in June 2015 to compensate men and women who were sterilized in the state's eugenics program; North Carolina sterilized 7,600 people from 1929 to 1974 who were deemed socially or mentally unfit.[116]

The Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) believes that mental disability is not a reason to deny sterilization. The opinion of ACOG is that "the physician must consult with the patient’s family, agents, and other caregivers" if sterilization is desired for a mentally limited patient.[117] In 2003, Douglas Diekema wrote in Volume 9 of the journal Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews that "involuntary sterilization ought not be performed on mentally retarded persons who retain the capacity for reproductive decision-making, the ability to raise a child, or the capacity to provide valid consent to marriage."[118] The Journal of Medical Ethics claimed, in a 1999 article, that doctors are regularly confronted with request to sterilize mentally limited people who cannot give consent for themselves. The article recommend that sterilization should only occur when there is a "situation of necessity" and the "benefits of sterilization outweigh the drawbacks."[119] The American Journal of Bioethics published an article, in 2010, that concluded the interventions used in the Ashley treatment may benefit future patients.[120] These interventions, at the request of the parents and guidance from the physicians, included a hysterectomy and surgical removal of the breast buds of the mentally and physically disabled child.[121]

The inability to pay for the cost of raising children has been a reason courts have ordered coercive or compulsory sterilization. In June 2014, a Virginia judge ruled that a man on probation for child endangerment must be able to pay for his seven children before having more children; the man agreed to get a vasectomy as part of his plea deal.[122] In 2013, an Ohio judge ordered a man owing nearly $100,000 in unpaid child support to "make all reasonable efforts to avoid impregnating a woman" as a condition of his probation.[123] Kevin Maillard wrote that conditioning the right to reproduction on meeting child support obligations amounts to "constructive sterilization" for men unlikely to make the payments.[124]

U.S. Criminal Justice System

In addition to eugenics purposes, sterilization was used as punitive tactic against sex offenders, people identified as homosexual, or people deemed to masturbate too much.[125] California, the first state in the U.S. to enact compulsory sterilization based on eugenics, sterilized all prison inmates under the 1909 sterilization law.[125] In the last 40 years, judges have offered lighter punishment (i.e. probation instead of jail sentence) to people willing to use contraception or be sterilized, particularly in child abuse/endangerment cases.[126] One of the most famous cases of this was People v. Darlene Johnson, during which Ms. Johnson, a woman charged with child abuse sentenced to seven years in prison, was offered probation and a reduced prison sentence if she agreed to use Norplant.[127]

In addition to child abuse cases, some politicians proposed bills mandating Norplant use among women on public assistance as a requirement to maintain welfare benefits.[127] As noted above, some judges offered probation in lieu of prison time to women who agreed to use Norplant, while other court cases have ordered parents to cease childbearing until regaining custody of their children after abuse cases. Some legal scholars and ethicists argue such practices are inherently coercive.[127] Furthermore, such scholars link these practices to eugenic policies of the 19thand early 20th century, highlighting how such practices not only targeted poor people, but disproportionately impacted minority women and families in the U.S., particularly black women.

In the late 1970s, to acknowledge the history of forced and coercive sterilizations and prevent ongoing eugenics/population control efforts, the federal government implemented a standardized informed consent process and specific eligibility criteria for government funded sterilization procedures.[128] Some scholars argue the extensive consent process and 30-day waiting period go beyond preventing instances of coercion and serve as a barrier to desired sterilization for women relying on public insurance.[128]

Though formal eugenics laws are no longer routinely implemented have been removed from government documents, instances of reproductive coercion still take place in U.S. institutions today. In 2011, investigative news released a report revealing between 2006 and 2011 148 female prisoners in two California state prisons were sterilized without adequate informed consent.[129] In September 2014, California enacted Bill SB 1135 that bans sterilization in correctional facilities, unless the procedure shall be required in a medical emergency to preserve inmate's life.[130]

Abuses at immigration detention centers

In 2020, multiple human rights groups joined a whistleblower to accuse a private-owned U.S. immigration detention centre in Georgia of forcibly sterilizing women. The reports claimed a doctor conducted unauthorized medical procedures on women detained by ICE.[131] The whistleblower, Dawn Wooten, was a nurse and former employee. She claims a high rate of sterilizations were performed on Spanish-speaking women and women who spoke various Indigenous languages common in Latin America. Wooten said the centre did not obtain proper consent for these surgeries, or lied to women about the medical procedures.

More than 40 women submitted testimony in writing to document these abuses, one attorney said.[132] Jerry Flores, a faculty member at the University of Toronto Mississauga said the alleged treatment of women constituted a violation of human rights and genocide according to the standards of the United Nations.[131] Just Security of the New York University School of Law said the U.S. bore "international responsibility for the forced sterilization of women in ICE detention".[133] Flores said that it was nothing new, and that the U.S. had a long history of forcibly sterilizing women from Latina, indigenous, and Black communities.[131]

In September 2020, Mexico demanded more information from US authorities on medical procedures performed on migrants in detention centers, after allegations that six Mexican women were sterilized without their consent. The ministry said consulate personnel had interviewed 18 Mexican women who were detained at the center, none of whom "claimed to have undergone a hysterectomy". Another women said she had undergone a gynecological operation, although there was nothing in her detention file to support she agreed to the procedure.[134]

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rican physician Dr. Lanauze Rolón founded the League for Birth Control in Ponce, Puerto Rico, in 1925, but the League was quickly squashed by opposition from the Catholic church.[135][136] A similar League was founded seven years later, in 1932, in San Juan and continued in operation for two years before opposition and lack of support forced its closure.[135][136] Yet another effort at establishing birth control clinics was made in 1934 by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration in a relief response to the conditions of the Great Depression.[136] As a part of this effort, 68 birth control clinics were opened on the island.[136] The next mass opening of clinics occurred in January 1937 when American Dr. Clarence Gamble, in association with a group of wealthy and influential Puerto Ricans, organized the Maternal and Infant Health Association and opened 22 birth control clinics.[136]

The Governor of Puerto Rico, Menendez Ramos, enacted Law 116,[137] which went into effect on May 13, 1937.[138] It was a birth control and eugenic sterilization law that allowed the dissemination of information regarding birth control methods and legalized the practice of birth control.[135][136] The government cited a growing population of the poor and unemployed as motivators for the law. Abortion remained heavily restricted. By 1965, approximately 34 percent of women of childbearing age had been sterilized, two thirds of whom were still in their early twenties. The law was repealed on June 8, 1960.[135]

1940s–1950s

Unemployment and widespread poverty would continue to grow in Puerto Rico in the 40s, both threatening U.S. private investment in Puerto Rico and acting as a deterrent for future investment.[135] In an attempt to attract additional U.S. private investment in Puerto Rico, another round of liberalizing trade policies were implemented and referred to as “Operation Bootstrap.”[135] Despite these policies and their relative success, unemployment and poverty in Puerto Rico remained high, high enough to prompt an increase in emigration from Puerto Rico to the United States between 1950 and 1955.[135] The issues of immigration, Puerto Rican poverty, and threats to U.S. private investment made population control concerns a prime political and social issue for the United States.[135]

The 50s also saw the production of social science research supporting sterilization procedures in Puerto Rico.[135] Princeton's Office of Population Research, in collaboration with the Social Research Department at the University of Puerto Rico, conducted interviews with couples regarding sterilization and other birth control.[135] Their studies concluded that there was a significant need and desire for permanent birth control among Puerto Ricans.[135] In response, Puerto Rico's governor and Commissioner of health opened 160 private, temporary birth control clinics with the specific purpose of sterilization.[135]

Also during this era, private birth control clinics were established in Puerto Rico with funds provided by wealthy Americans.[135][136] Joseph Sunnen, a wealthy American Republican and industrialist, established the Sunnen Foundation in 1957.[135][136] The foundation funded new birth control clinics under the title “La Asociación Puertorriqueña el Biensestar de la Familia” and spent hundreds of thousands of dollars in an experimental project to determine if a formulaic program could be used to control population growth in Puerto Rico and beyond.[135]

Sterilization procedures and coercion

From beginning of the 1900s, U.S. and Puerto Rican governments espoused rhetoric connecting the poverty of Puerto Rico with overpopulation and the “hyper-fertility” of Puerto Ricans.[139] Such rhetoric combined with eugenics ideology of reducing “population growth among a particular class or ethnic group because they are considered...a social burden,” was the philosophical basis for the 1937 birth control legislation enacted in Puerto Rico.[139][140] A Puerto Rican Eugenics Board, modeled after a similar board in the United States, was created as part of the bill, and officially ordered ninety-seven involuntary sterilizations.[140]

The legalization of sterilization was followed by a steady increase in the popularity of the procedure, both among the Puerto Rican population and among physicians working in Puerto Rico.[140][141] Though sterilization could be performed on men and women, women were most likely to undergo the procedure.[135][136][140][141] Sterilization was most frequently recommended by physicians because of a pervasive belief that Puerto Ricans and the poor were not intelligent enough to use other forms of contraception.[140][141] Physicians and hospitals alike also implemented hospital policy to encourage sterilization, with some hospitals refusing to admit healthy pregnant women for delivery unless they consented to be sterilized.[140][141] This has been best documented at Presbyterian Hospital, where the unofficial policy for a time was to refuse admittance for delivery to women who already had three living children unless she consented to sterilization.[140][141] There is additional evidence that true informed consent was not obtained from patients before they underwent sterilization, if consent was solicited at all.[141]

By 1949 a survey of Puerto Rican women found that 21% of women interviewed had been sterilized, with sterilizations being performed in 18% of all hospital births statewide as a routine post-partum procedure, with the sterilization operation performed before women left the hospitals after giving birth.[135] As for the birth control clinics founded by Sunnen, the Puerto Rican Family Planning Association reported that around 8,000 women and 3,000 men had been sterilized in Sunnen's privately funded clinics.[135] At one point, the levels of sterilization in Puerto Rico were so high that they alarmed the Joint Committee for Hospital Accreditation, who then demanded that Puerto Rican hospitals limit sterilizations to ten percent of all hospital deliveries in order to receive accreditation.[135] The high popularity of sterilization continued into the 60s and 70s, during which the Puerto Rican government made the procedures available for free and reduced fees.[140] The effects of the sterilization and contraception campaigns of the 1900s in Puerto Rico are still felt in Puerto Rican cultural history today.[139]

Controversy and opposing viewpoints

There has been much debate and scholarly analysis concerning the legitimacy of choice given to Puerto Rican women with regards to sterilization, reproduction, and birth control, as well as with the ethics of economically motivated mass sterilization programs.

Some scholars, such as Bonnie Mass[135] and Iris Lopez,[139] have argued that the history and popularity of mass sterilization in Puerto Rico represents a government-led eugenics initiative for population control.,[135][139][141][142] They cite the private and government funding of sterilization, coercive practices, and the eugenics ideology of Puerto Rican and American governments and physicians as evidence of a mass sterilization campaign.[139][141][142]

On the other side of the debate, scholars like Laura Briggs[140] have argued that evidence does not substantiate claims of a mass sterilization program.[140] She further argues that reducing the popularity of sterilization in Puerto Rico to a state initiative ignores the legacy of Puerto Rican feminist activism in favor or birth control legalization and the individual agency of Puerto Rican women in making decisions about family planning.[140]

Effects

When the United States took census of Puerto Rico in 1899, the birth rate was 40 births per one thousand people.[136] By 1961, the birth rate had dropped to 30.8 per thousand.[135] In 1955, 16.5% of Puerto Rican women of childbearing age had been sterilized, this jumped to 34% in 1965.[135]

In 1969, sociologist Harriet Presser analyzed the 1965 Master Sample Survey of Health and Welfare in Puerto Rico.[143] She specifically analyzed data from the survey for women ages 20 to 49 who had at least one birth, resulting in an overall sample size of 1,071 women.[143] She found that over 34% of women aged 20–49 had been sterilized in Puerto Rico in 1965.[143]

Presser's analysis also found that 46.7% of women who reported they were sterilized were between the ages of 34 and 39.[143] Of the sample of women sterilized, 46.6% had been married 15 to 19 years, 43.9% had been married for 10-to-14 years, and 42.7% had been married for 20-to-24 years.[143] Nearly 50% of women sterilized had three or four births.[143] Over 1/3 of women who reported being sterilized were sterilized in their twenties, with the average age of sterilization being 26.[143]

A survey by a team of Americans in 1975 confirmed Presser's assessment that nearly 1/3 of Puerto Rican women of childbearing age had been sterilized.[135] As of 1977, Puerto Rico had the highest proportion of childbearing-aged persons sterilized in the world.[135] In 1993, ethnographic work done in New York by anthropologist Iris Lopez[139] showed that the history of sterilization continued to effect the lives of Puerto Rican women even after they immigrated to the United States and lived there for generations.[139] The history of the popularity of sterilization in Puerto Rico meant that Puerto Rican women living in America had high rates of female family members who had undergone sterilization, and it remained a highly popular form of birth control among Puerto Rican women living in New York.[139]

Mexico

“Civil Society Organizations such as Balance, Promocion para el Desarrollo y Juventud, A.C., have received in the last years numerous testimonies of women living with HIV in which they inform that misinformation about the virus transmission has frequently lead to compulsory sterilization. Although there is enough evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions aimed to reduce mother-to-child transmission risks, there are records of HIV-positive women forced to undergo sterilization or have agreed to be sterilized without adequate and sufficient information about their options.”[144]

A report made in El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, and Nicaragua concluded that women living with HIV, and whose health providers knew about it at the time of pregnancy, were six times more likely to experience forced or coerced sterilization in those countries. In addition, most of these women reported that health providers told them that living with HIV cancelled their right to choose the number and spacing of the children they want to have as well as the right to choose the contraceptive method of their choice; provided misleading information about the consequences for their health and that of their children and denied them access to treatments that reduce mother-to-child HIV transmission in order to coerce them into sterilization.[145]

This happens even when the health norm NOM 005-SSA2-1993 states that family planning is "the right of everyone to decide freely, responsibly and in an informed way the number and spacing of their children and to obtain specialized information and proper services” and that “the exercise of this right is independent of gender, age, and social or legal status of persons".[144]

Uzbekistan

According to reports, as of 2012, forced and coerced sterilization are current Government policy in Uzbekistan for women with two or three children as a means of forcing population control and to improve maternal mortality rates.[146][147][148][149][150] In November 2007, a report by the United Nations Committee Against Torture reported that "the large number of cases of forced sterilization and removal of reproductive organs of women at reproductive age after their first or second pregnancy indicate that the Uzbek government is trying to control the birth rate in the country" and noted that such actions were not against the national Criminal Code[151] in response to which the Uzbek delegation to the associated conference was "puzzled by the suggestion of forced sterilization, and could not see how this could be enforced."[152]

Reports of forced sterilizations, hysterectomies and IUD insertions first emerged in 2005,[146][147][148][153] although it is reported that the practice originated in the late 1990s,[154] with reports of a secret decree dating from 2000.[153] The current policy was allegedly instituted by Islam Karimov under Presidential Decree PP-1096, "on additional measures to protect the health of the mother and child, the formation of a healthy generation"[155] which came into force in 2009.[156] In 2005 Deputy Health Minister Assomidin Ismoilov confirmed that doctors in Uzbekistan were being held responsible for increased birth rates.[153]

Based on a report by journalist Natalia Antelava, doctors reported that the Ministry of Health told doctors they must perform surgical sterilizations on women. One doctor reported, “It's ruling number 1098 and it says that after two children, in some areas after three, a woman should be sterilized.”, in a loss of the former surface decency of Central Asian mores in regard of female chastity.[157] In 2010, the Ministry of Health passed a decree stating all clinics in Uzbekistan should have sterilization equipment ready for use. The same report also states that sterilization is to be done on a voluntary basis with the informed consent of the patient.[157] In the 2010 Human Rights Report of Uzbekistan, there were many reports of forced sterilization of women along with allegations of the government pressuring doctors to sterilize women in order to control the population.[158] Doctors also reported to Antelava that there are quotas they must reach every month on how many women they need to sterilize. These orders are passed on to them through their bosses and, allegedly, from the government.[157]

On May 15, 2012, during a meeting with the Russian president Vladimir Putin in Moscow the Uzbek president Islam Karimov said: "we are doing everything in our hands to make sure that the population growth rate [in Uzbekistan] does not exceed 1.2–1.3"[159] The Uzbek version of RFE/RL reported that with this statement Karimov indirectly admitted that forced sterilization of women is indeed taking place in Uzbekistan.[159] The main Uzbek television channel, O'zbekiston, cut out Karimov's statement about the population growth rate while broadcasting his conversation with Putin.[159] It is unclear if there is any genocidal conspiracy in regard of the Mongol type involved, in connection with genetic drain of this type through lack of their reproduction.

Despite international agreement concerning the inhumanity and illegality of forced sterilization, it has been suggested that the Government of Uzbekistan continues to pursue such programs.[146]

Other countries

Eugenics programs including forced sterilization existed in most Northern European countries, as well as other more or less Protestant countries. Other countries that had notably active sterilisation programmes include Denmark, Norway, Finland,[160] Estonia, Switzerland, Iceland, and some countries in Latin America (including Panama).

In the United Kingdom, Home Secretary Winston Churchill was a noted advocate, and his successor Reginald McKenna introduced a bill that included forced sterilisation. Writer G. K. Chesterton led a successful effort to defeat that clause of the 1913 Mental Deficiency Act.[161]

In one specific case in 2015, the Court of Protection of the United Kingdom ruled that a woman with six children and an IQ of 70 should be sterilized for her own safety because another pregnancy would have been a "significantly life-threatening event" for her and the fetus and was not releated to eugenics.[162]

See also

References

- Webster University, Forced Sterilization. Retrieved on August 30, 2014. "Women and Global Human Rights". Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization: An interagency statement Archived 2015-07-11 at the Wayback Machine, World Health Organization, May 2014.

- "Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (A/HRC/22/53)" (PDF). Ohchr.org. para. 78. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- Correa, Sonia (1994). Population and Reproductive Rights: Feminists Perspectives from the South. London: Zed Books Ltd. p. 11. ISBN 9781856492843.

- Solinger, Rickie (2005). Pregnancy and Power: A Short History of Reproductive Politics in America. New York: New York University Press. p. 90. ISBN 9780814798287.

- Lopez, Iris (2008). Matters of Choice: Puerto Rican Women's Struggle for Reproductive Freedom. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. xiii. ISBN 9780813543734.

- Rylko-Bauer, Barbara (2014). A Polish Doctor in the Nazi Camps: My Mother's Memories of Imprisonment, Immigration, and a Life Remade. University of Oklahoma. pp. 91–92. ISBN 9780806145860.

- Baxandall, Rosalyn; Gordon, Linda (2000). Dear Sisters. New York, NY: Basic Books. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-465-01707-2.

- "Interact Worldwide Downloads". Interact Worldwide. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011.

- Egnor, Michael (14 August 2009). "The Inconvenient Truth About Population Control, Part 2; Science Czar John Holdren's Endorsement of Involuntary Sterilization". evolutionnews.org. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- Goldberg, Michelle (21 July 2009). "Holdren's Controversial Population Control Past". The American Prospect. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- McCoy, Terrence. "The forgotten roots of India's mass sterilization program". Washington Post. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Heer, David M. (March 1975). "Marketable licenses for babies: Boulding's proposal revisited". Social Biology. 22 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/19485565.1975.9988142. ISSN 0037-766X. PMID 1188404.

- Russett, Bruce M. (June 1970). "Communications". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 14 (2): 287–291. doi:10.1177/002200277001400209. ISSN 0022-0027. S2CID 220640867.

- "The Human Predicament: Finding a Way Out" (PDF).

- "Glenn Beck claims science czar John Holdren proposed forced abortions and putting sterilants in the drinking water to control population". PolitiFact. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Mann, Charles C. "The Book That Incited a Worldwide Fear of Overpopulation". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Hartmann, Betsy, author. (2016). Reproductive rights and wrongs : the global politics of population control. ISBN 978-1-60846-733-4. OCLC 945949149.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "A Post-Colonial Feminist Critique of Population Control Policies -". Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- "Feminist Perspectives on Population Issues | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Bhatia, Rajani; Sasser, Jade S.; Ojeda, Diana; Hendrixson, Anne; Nadimpally, Sarojini; Foley, Ellen E. (3 April 2019). "A feminist exploration of 'populationism': engaging contemporary forms of population control". Gender, Place & Culture. 27 (3): 333–350. doi:10.1080/0966369x.2018.1553859. ISSN 0966-369X. S2CID 150974096.

- "Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence". Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- Horton, Guy (April 2005). "12.52 Crimes against humanity" (PDF). Dying Alive – A Legal Assessment of Human Rights Violations in Burma. The Netherlands Ministry for Development Co-Operation. p. 201. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2016. Horton references RSICC/C, Vol. 1 p. 360

- "Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court". legal.un.org. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- "Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court". United Nations Treaty Collection. United Nations. Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Forced Sterilization and Mandatory Divorce: How a Majority of Council of Europe Member States' Laws Regarding Gender Identity Violate the Internationally and Regionally Established Human Rights of Trans* People". 33 (1 Article 9). Berkeley Journal of International Law. 2015. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

Unfortunately, this is not an anomaly: this is the lived experience of trans* people in dozens of countries throughout the world, including the twenty-one Council of Europe (COE) Member States that currently require proof of sterilization to change one's legal sex categorization. […] It would be advisable for LGBTQ activists to seriously consider developing LGBTQ-specific international and regional human rights treaties.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "পরিবার পরিকল্পনা | উত্তরখান ইউনিয়ন | উত্তরখান ইউনিয়ন". uttarkhanup.dhaka.gov.bd. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- AR, Khan; I, Swenson (1978). "Acceptability of male sterilization in Bangladesh: its problems and perspectives". Bangladesh Development Studies. 6 (2). Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- L, Liskin; JM, Pile; WF, Quillan (1983). "Vasectomy—safe and simple". Population Reports. Series D: Sterilization Male (4). Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- Khan, Atiqur Rahman; Swenson, Ingrid E.; Rahman, Azizur (1 January 1979). "A Follow-up of Vasectomy Clients in Rural Bangladesh". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 17 (1): 11–14. doi:10.1002/j.1879-3479.1979.tb00108.x. ISSN 1879-3479. PMID 39831. S2CID 22375165.

- Claiborne, William (28 January 1983). "Bangladesh's Midwives Promote Birth Control". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- "The Bangladesh government plans a mass voluntary sterilization of..." UPI. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "Impoverished Bangladesh plans sterilization program". UPI. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Miles and Shiva 1993

- Rosenberg, M. J.; Rochat, R. W.; Akbar, J.; Gould, P.; Khan, A. R.; Measham, A.; Jabeen, S. (August 1982). "Sterilization in Bangladesh: mortality, morbidity, and risk factors". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 20 (4): 283–291. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(82)90057-1. ISSN 0020-7292. PMID 6127262. S2CID 26123485.

- Grimes, D. A.; Peterson, H. B.; Rosenberg, M. J.; Fishburne, J. I.; Rochat, R. W.; Khan, A. R.; Islam, R. (April 1982). "Sterilization-attributable deaths in bangladesh". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 20 (2): 149–154. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(82)90029-7. ISSN 0020-7292. PMID 6125437. S2CID 24472598.

- Grimes, D. A.; Satterthwaite, A. P.; Rochat, R. W.; Akhter, N. (November 1982). "Deaths from contraceptive sterilization in bangladesh: rates, causes, and prevention". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 60 (5): 635–640. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 7145254.

- AsiaNews.it. "BANGLADESH Healthcare in Bangladesh: only sterilization and vasectomies are free". www.asianews.it. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- "স্থায়ী জন্মনিয়ন্ত্রণ পদ্ধতির সেবা". www.nhd.gov.bd. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- Hartmann, B. (June 1991). "[Children and bankers in Bangladesh]". Temas de Poblacion. 1 (2): 51–55. PMID 12284143.

- "Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics". 4 September 2011. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- solutions, EIU digital. "Global Liveability Ranking 2015 – The Economist Intelligence Unit". www.eiu.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- "Dhaka 2nd least liveable city in the world". The Daily Star. 19 August 2015. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- "Bangladesh to offer sterilisation to Rohingya in refugee camps". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 28 October 2017. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- "Bangladesh 'plans to offer to sterilise Rohingya Muslims' as refugee population grows". The Independent. 29 October 2017. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- Hartmann, Betsy (2016). Reproductive Rights and Wrongs: The Global Politics of Population Control. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

- Dalsgaard, Anne Line (2004). Matters of Life and Longing: Female Sterilisation in Northeast Brazil. Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Corrêa, Sonia; Petchesky, Rosalind (1994). Reproductive and Sexual Rights: A Feminist Perspective. United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. 134–147.

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) (9 November 1999). "Alberta Apologizes for Forced Sterilization". CBC News. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "Victims of sterilization finally get day in court. Lawrence Journal-World. December 23, 1996". Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Indigenous women kept from seeing their newborn babies until agreeing to sterilization, says lawyer | CBC Radio". Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- "Human rights groups call on Canada to end coerced sterilization of indigenous women". The Guardian. 18 November 2018. Archived from the original on 8 February 2019.