Filipinos

Filipinos (Filipino: Mga Pilipino)[41] are the people who are native to or citizens of the country of the Philippines. Filipinos come from various Austronesian ethnolinguistic groups. Currently, there are more than 185 ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines; each with its own language, identity, culture and history. The number of individual languages listed for Philippines is 185. Of these, 183 are living and 2 are extinct. Of the living languages, 175 are indigenous and 8 are non-indigenous. Furthermore, as of 2019, 39 are institutional, 67 are developing, 38 are vigorous, 28 are endangered, and 11 are dying.[42]

Names

The name Filipino was derived from the term las Islas Filipinas ("the Philippine Islands"),[43] the name given to the archipelago in 1543 by the Spanish explorer and Dominican priest Ruy López de Villalobos, in honour of Philip II of Spain (Spanish: Felipe II).

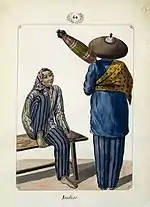

During the Spanish colonial period, natives of the Philippine islands were usually known by the generic terms indio ("Indian") or indigenta ("indigents").[44] However, even during the early Spanish colonial period the term Filipino was already being used to refer to the indio natives of the Philippine archipelago, especially when it was necessary to distinguish the indios of the Philippines from the indios of the Spanish colonies in other parts of the world.[45]

The usage of the word Filipino to refer to the natives appear in many early Spanish-era works and writings, such as in the Relación de las Islas Filipinas (1604) of Pedro Chirino, in which he wrote chapters entitled "Of the civilities, terms of courtesy, and good breeding among the Filipinos" (Chapter XVI), "Of the Letters of the Filipinos" (Chapter XVII), "Concerning the false heathen religion, idolatries, and superstitions of the Filipinos" (Chapter XXI), "Of marriages, dowries, and divorces among the Filipinos" (Chapter XXX),[46] while also using the term "Filipino" to refer unequivocally to the non-Spaniard natives of the archipelago like in the following sentence:

The first and last concern of the Filipinos in cases of sickness was, as we have stated, to offer some sacrifice to their anitos, or diwatas, which were their gods.[47]

— Pedro Chirino, Relación de las Islas Filipinas

In the Crónicas (1738) of Juan Francisco de San Antonio, the author devoted a chapter to "The Letters, languages and politeness of the Philippinos", while Francisco Antolín argued in 1789 that "the ancient wealth of the Philippinos is much like that which the Igorots have at present".[48] These examples prompted the historian William Henry Scott to conclude that during the Spanish colonial period:

[...]the people of the Philippines were called Filipinos when they were practicing their own culture — or, to put it another way, before they became indios.[49]

— William Henry Scott, Barangay- Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society

In the 19th century, Philippine-born Spaniards began to be called españoles filipinos, logically contracted to just Filipino, to distinguish them from the Spaniards born in Spain (the españoles europeos). However, they themselves resented the term, preferring to identify themselves as hijos del país (sons of the country). During this period, the natives were sometimes differentiated as indios filipinos to avoid confusion with the españoles filipinos.[50]

Historian Ambeth Ocampo has suggested that the first documented use of the word Filipino as a self-reference by a native was the Spanish-language poem A la juventud filipina, published in 1879 by José Rizal.[51] Writer and publisher Nick Joaquin has asserted that Luis Rodríguez Varela was the first to describe himself as Filipino in print.[52] Apolinario Mabini (1896) used the term Filipino to refer to all inhabitants of the Philippines. Father Jose Burgos earlier called all natives of the archipelago as Filipinos.[53]

The lack of the letter "F" in the pre-1987 Tagalog alphabet (Abakada) caused the letter "P" to be substituted for "F", though the alphabets and/or writing scripts of some non-Tagalog ethnic groups included the letter "F". Upon official adoption of the modern, 28-letter Filipino alphabet in 1987, the term Filipino was preferred over Pilipino. Locally, some still use "Pilipino" to refer to the people and "Filipino" to refer to the language, but in international use "Filipino" is the usual form for both.

A number of Filipinos refer to themselves colloquially as "Pinoy" (feminine: "Pinay"), which is a slang word formed by taking the last four letters of "Filipino" and adding the diminutive suffix "-y".

In 2020, the neologism Filipinx appeared; a demonym applied only to those of Filipino heritage in the diaspora, and specifically referring to and coined by Filipino-Americans imitating Latinx, itself a recently coined gender-inclusive alternative to Latino or Latina. An online dictionary made an entry of the term, applying it to all Filipinos within the Philippines or in the diaspora.[54] In actual practice, however, the term is unknown among and not applied to Filipinos living in the Philippines, and Filipino itself is already treated as gender-neutral. The inaccurate statement entry in the dictionary resulted in confusion, backlash and ridicule from Filipinos residing in the Philippines who have never identified themselves with the foreign term.[55][56]

Native Filipinos were also called Manilamen (or Manila men) or Tagalas by English-speaking regions during the colonial era. They were mostly sailors and pearl-divers and established communities in various ports around the world.[57] [58] One of the notable settlements of Manilamen is the community of Saint Malo, Louisiana, founded at around 1763 to 1765 by escaped slaves and deserters from the Spanish Navy.[59][60][61][62] There were also significant numbers of Manilamen in Northern Australia and the Torres Strait Islands in the late 1800s who were employed in the pearl hunting industries.[63][64]

In Latin America (especially in the Mexican states of Guerrero and Colima), Filipino immigrants arriving to New Spain during the 16th and 17th centuries via the Manila galleons were called chino, which led to the confusion of early Filipino immigrants with that of the much later Chinese immigrants to Mexico from the 1880s to the 1940s. A genetic study in 2018 has also revealed that around one-third of the population of Guerrero have 10% Filipino ancestry.[65][66]

History

Prehistory

In 2010, a metatarsal from "Callao Man", discovered in 2007, was dated through uranium-series dating as being 67,000 years old.[67]

Prior to that, the earliest human remains found in the Philippines were thought to be the fossilized fragments of a skull and jawbone, discovered in the 1960s by Dr. Robert B. Fox, an anthropologist from the National Museum.[68] Anthropologists who examined these remains agreed that they belonged to modern human beings. These include the Homo sapiens as distinguished from the mid-Pleistocene Homo erectus species.

The "Tabon Man" fossils are considered to have come from a third group of inhabitants, who worked the cave between 22,000 and 20,000 BCE. An earlier cave level lies so far below the level containing cooking fire assemblages that it must represent Upper Pleistocene dates like 45 or 50 thousand years ago.[69] Researchers say this indicates that the human remains were pre-Mongoloid, from about 40,000 years ago. Mongoloid is the term which anthropologists applied to the ethnic group which migrated to Southeast Asia during the Holocene period and evolved into the Austronesian people (associated with the Haplogroup O1 (Y-DNA) genetic marker), a group of Malayo-Polynesian-speaking people including those from Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Malagasy, the non-Chinese Taiwan Aboriginals or Rhea's.[70]

Fluctuations in ancient shorelines between 150,000 BC and 17,000 BC connected the Malay Archipelago region with Maritime Southeast Asia and the Philippines. This may have enabled ancient migrations into the Philippines from Maritime Southeast Asia approximately 50,000 BC to 13,000 BC.[71]

A January 2009 study of language phylogenies by R. D. Gray at the University of California, Los Angeles published in the journal Science, suggests that the population expansion of Austronesian peoples was triggered by rising sea levels of the Sunda shelf at the end of the last ice age. This was a two-pronged expansion, which moved north through the Philippines and into Taiwan, while a second expansion prong spread east along the New Guinea coast and into Oceania and Polynesia.[72]

The Negritos are likely descendants of the indigenous populations of the Sunda landmass and New Guinea, pre-dating the Mongoloid peoples who later entered Southeast Asia.[73] Multiple studies also show that Negritos from Southeast Asia to New Guinea share a closer cranial affinity with Australo-Melanesians.[73][74] They were the ancestors of such tribes of the Philippines as the Aeta, Agta, Ayta, Ati, Dumagat and other similar groups. Today they comprise just 0.03% of the total Philippine population.[75]

The majority of present-day Filipinos are a product of the long process of evolution and movement of people.[76] After the mass migrations through land bridges, migrations continued by boat during the maritime era of South East Asia. The ancient races became homogenized into the Malayo-Polynesians which colonized the majority of the Philippine, Malaysian and Indonesian archipelagos.[77][78]

Archaic epoch (to 1565)

Since at least the 3rd century, various ethnic groups established several communities. These were formed by the assimilation of various native Philippine kingdoms.[75] South Asian and East Asian people together with the people of the Indonesian archipelago and the Malay Peninsula, traded with Filipinos and introduced Hinduism and Buddhism to the native tribes of the Philippines. Most of these people stayed in the Philippines where they were slowly absorbed into local societies.

Many of the barangay (tribal municipalities) were, to a varying extent, under the de jure jurisprudence of one of several neighboring empires, among them the Malay Srivijaya, Javanese Majapahit, Brunei, Malacca, Indian Chola, Champa and Khmer empires, although de facto had established their own independent system of rule. Trading links with Sumatra, Borneo, Java, Cambodia, Malay Peninsula, Indochina, China, Japan, India and Arabia. A thalassocracy had thus emerged based on international trade.

Even scattered barangays, through the development of inter-island and international trade, became more culturally homogeneous by the 4th century. Hindu-Buddhist culture and religion flourished among the noblemen in this era.

In the period between the 7th to the beginning of the 15th centuries, numerous prosperous centers of trade had emerged, including the Kingdom of Namayan which flourished alongside Manila Bay,[79][80] Cebu, Iloilo,[81] Butuan, the Kingdom of Sanfotsi situated in Pangasinan, the Kingdom of Luzon now known as Pampanga which specialized in trade with most of what is now known as Southeast Asia, and with China, Japan and the Kingdom of Ryukyu in Okinawa.

From the 9th century onwards, a large number of Arab traders from the Middle East settled in the Malay Archipelago and intermarried with the local Malay, Bruneian, Malaysian, Indonesian, and Luzon and Visayas indigenous populations.[82]

In the years leading up to 1000 AD, there were already several maritime societies existing in the islands but there was no unifying political state encompassing the entire Philippine archipelago. Instead, the region was dotted by numerous semi-autonomous barangays (settlements ranging is size from villages to city-states) under the sovereignty of competing thalassocracies ruled by datus, rajahs or sultans[83] or by upland agricultural societies ruled by "petty plutocrats". States such as the Wangdoms of Ma-i and Pangasinan, Kingdom of Maynila, Namayan, the Kingdom of Tondo, the Kedatuans of Madja-as, and Dapitan, the Rajahnates of Butuan and Cebu and the sultanates of Maguindanao, Lanao and Sulu existed alongside the highland societies of the Ifugao and Mangyan.[84][85][86][87] Some of these regions were part of the Malayan empires of Srivijaya, Majapahit and Brunei.[88][89][90]

Historic caste systems

Datu – The Tagalog maginoo, the Kapampangan ginu, and the Visayan tumao were the nobility social class among various cultures of the pre-colonial Philippines. Among the Visayans, the tumao were further distinguished from the immediate royal families, or a ruling class.

Timawa – The timawa class were free commoners of Luzon and the Visayas who could own their own land and who did not have to pay a regular tribute to a maginoo, though they would, from time to time, be obliged to work on a datu's land and help in community projects and events. They were free to change their allegiance to another datu if they married into another community or if they decided to move.

Maharlika – Members of the Tagalog warrior class known as maharlika had the same rights and responsibilities as the timawa, but in times of war they were bound to serve their datu in battle. They had to arm themselves at their own expense, but they did get to keep the loot they took. Although they were partly related to the nobility, the maharlikas were technically less free than the timawas because they could not leave a datu's service without first hosting a large public feast and paying the datu between 6 and 18 pesos in gold – a large sum in those days.

Alipin – Commonly described as "servant" or "slave". However, this is inaccurate. The concept of the alipin relied on a complex system of obligation and repayment through labor in ancient Philippine society, rather than on the actual purchase of a person as in Western and Islamic slavery. Members of the alipin class who owned their own houses were more accurately equivalent to medieval European serfs and commoners.

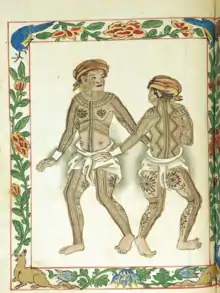

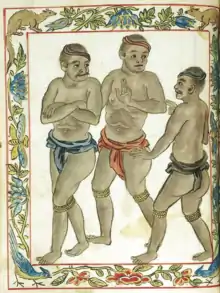

By the 15th century, Arab and Indian missionaries and traders from Malaysia and Indonesia brought Islam to the Philippines, where it both replaced and was practiced together with indigenous religions. Before that, indigenous tribes of the Philippines practiced a mixture of Animism, Hinduism and Buddhism. Native villages, called barangays were populated by locals called Timawa (Middle Class/ freemen) and Alipin (servants & slaves). They were ruled by Rajahs, Datus and Sultans, a class called Maginoo (royals) and defended by the Maharlika (Lesser nobles, royal warriors and aristocrats).[75] These Royals and Nobles are descended from native Filipinos with varying degrees of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian, which is evident in today's DNA analysis among South East Asian Royals. This tradition continued among the Spanish and Portuguese traders who also intermarried with the local populations.[91]

Hispanic settlement and rule (1521–1898)

The Philippines was settled by the Spanish. The arrival of Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan (Portuguese: Fernão de Magalhães) in 1521 began a period of European colonization. During the period of Spanish colonialism the Philippines was part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which was governed and controlled from Mexico City. Early Spanish settlers were mostly explorers, soldiers, government officials and religious missionaries born in Spain and Mexico. Most Spaniards who settled were of Andalusian ancestry but there were also Catalan, Moorish and Basque settlers. The Peninsulares (governors born in Spain), mostly of Castilian ancestry, settled in the islands to govern their territory. Most settlers married the daughters of rajahs, datus and sultans to reinforce the colonization of the islands. The Ginoo and Maharlika castes (royals and nobles) in the Philippines prior to the arrival of the Spanish formed the privileged Principalía (nobility) during the Spanish period.

The arrival of the Spaniards to the Philippines attracted new waves of immigrants from China, and maritime trade flourished during the Spanish period. The Spanish recruited thousands of Chinese migrant workers called sangleys to build the colonial infrastructure in the islands. Many Chinese immigrants converted to Christianity, intermarried with the locals, and adopted Hispanized names and customs and became assimilated, although the children of unions between Filipinos and Chinese that became assimilated continued to be designated in official records as mestizos de sangley. The Chinese mestizos were largely confined to the Binondo area until the 19th century. However, they eventually spread all over the islands, and became traders, landowners, and moneylenders.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of Japanese traders also migrated to the Philippines and assimilated into the local population.[92]

British forces occupied Manila between 1762 and 1764 as a part of the Seven Years' War,. However, the only part of the Philippines which the British held was the Spanish colonial capital of Manila and the principal naval port of Cavite, both of which are located on Manila Bay. The war was ended by the Treaty of Paris (1763). At the end of the war the treaty signatories were not aware that Manila had been taken by the British and was being administered as a British colony. Consequently, no specific provision was made for the Philippines. Instead they fell under the general provision that all other lands not otherwise provided for be returned to the Spanish Empire.[93] Many Indian Sepoy troops and their British captains mutinied and were left in Manila and some parts of the Ilocos and Cagayan. The ones in Manila settled at Cainta, Rizal and the ones in the north settled in Isabela. Most were assimilated into the local population.

A total of 110 Manila-Acapulco galleons set sail between 1565 and 1815, during the Philippines trade with Mexico. Until 1593, three or more ships would set sail annually from each port bringing with them the riches of the archipelago to Spain. European criollos, mestizos and Portuguese, French and Mexican descent from the Americas, mostly from Latin America came in contact with the Filipinos. Japanese, Indian and Cambodian Christians who fled from religious persecutions and killing fields also settled in the Philippines during the 17th until the 19th centuries.

With the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1867, Spain opened the Philippines for international trade. European investors such as British, Dutch, German, Portuguese, Russian, Italian and French were among those who settled in the islands as business increased. More Spaniards arrived during the next century. Many of these European migrants intermarried with local mestizos and assimilated with the indigenous population.

Late modern

After the defeat of Spain during the Spanish–American War in 1898, Filipino general, Emilio Aguinaldo declared independence on June 12 while General Wesley Merritt became the first American governor of the Philippines. On December 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris formally ended the war, with Spain ceding the Philippines and other colonies to the United States in exchange for $20 million.[94]

[95] The Philippine–American War resulted in the deaths of at least 200,000 Filipino civilians.[96] Some estimates for total civilian dead reach up to 1,000,000.[97][98] After the Philippine–American War, the United States civil governance was established in 1901, with William Howard Taft as the first American Governor-General.[99] A number of Americans settled in the islands and thousands of interracial marriages between Americans and Filipinos have taken place since then. Due to the strategic location of the Philippines, as many as 21 bases and 100,000 military personnel were stationed there since the United States first colonized the islands in 1898. These bases were decommissioned in 1992 after the end of the Cold War, but left behind thousands of Amerasian children.[100] The country gained independence from the United States in 1946. The Pearl S. Buck International Foundation estimates there are 52,000 Amerasians scattered throughout the Philippines. However, according to the center of Amerasian Research, there might be as many as 250,000 Amerasians scattered across the cities of Clark, Angeles, Manila, and Olongapo.[101] In addition, numerous Filipino men enlisted in the US Navy and made careers in it, often settling with their families in the United States. Some of their second- or third-generation families returned to the country.

%252C_with_representatives_from_the_Philippine_Independence_Mission_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Following its independence, the Philippines has seen both small and large-scale immigration into the country, mostly involving American, European, Chinese, and Japanese peoples. After World War II, South Asians continued to migrate into the islands, most of which assimilated and avoided the local social stigma instilled by the early Spaniards against them by keeping a low profile and/or by trying to pass as Spanish mestizos. This was also true for the Arab and Chinese immigrants, many of whom are also post WWII arrivals. More recent migrations into the country by Koreans, Persians, Brazilians, and other Southeast Asians have contributed to the enrichment of the country's ethnic landscape, language and culture. Centuries of migration, diaspora, assimilation, and cultural diversity made most Filipinos accepting of interracial marriage and multiculturalism.

Philippine nationality law is currently based upon the principle of jus sanguinis and, therefore, descent from a parent who is a citizen of the Republic of the Philippines is the primary method of acquiring national citizenship. Birth in the Philippines to foreign parents does not in itself confer Philippine citizenship, although RA9139, the Administrative Naturalization Law of 2000, does provide a path for administrative naturalization of certain aliens born in the Philippines.

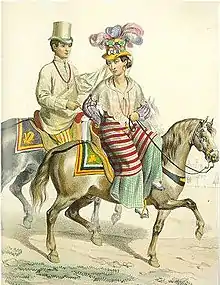

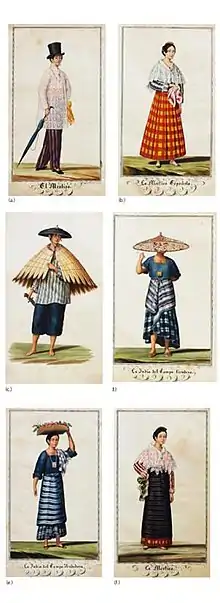

Social classifications

Filipinos of mixed ethnic origins are still referred to today as mestizos. However, in common parlance, mestizos are only used to refer to Filipinos mixed with Spanish or any other European ancestry. Filipinos mixed with any other foreign ethnicities are named depending on the non-Filipino part.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Negrito | indigenous person of purely Negrito ancestry |

| Indio | indigenous person of purely Austronesian ancestry |

| Moros | indigenous person of the Islamic faith living in the Archipelago of the Philippines |

| Sangley/Chino | person of purely Chinese ancestry |

| Mestizo de Sangley/Chino | person of mixed Chinese and Austronesian ancestry |

| Mestizo de Español | person of mixed Spanish and Austronesian ancestry |

| Tornatrás | person of mixed Spanish, Austronesian and Chinese ancestry |

| Insulares/Filipino | person of purely Spanish descent born in the Philippines |

| Americanos | person of Criollo (either pure Spanish blood, or mostly), Castizo (1/4 Native American, 3/4 Spanish) or Mestizo (1/2 Spanish, 1/2 Native American) descent born in Spanish America ("from the Americas") |

| Peninsulares | person of purely Spanish descent born in Spain ("from the Iberian peninsula") |

People classified as 'blancos' (whites) were the insulares or "Filipinos" (a person born in the Philippines of pure Spanish descent), peninsulares (a person born in Spain of pure Spanish descent), Español mestizos (a person born in the Philippines of mixed Austronesian and Spanish ancestry), and tornatrás (a person born in the Philippines of mixed Austronesian, Chinese and Spanish ancestry). Manila was racially segregated, with blancos living in the walled city of Intramuros, un-Christianized sangleys in Parían, Christianized sangleys and mestizos de sangley in Binondo, and the rest of the 7,000 islands for the indios, with the exception of Cebu and several other Spanish posts. Only mestizos de sangley were allowed to enter Intramuros to work for whites (including mestizos de español) as servants and various occupations needed for the colony. Indio were native Austronesians, but as a legal classification, Indio were those who embraced Roman Catholicism and Austronesians who lived in proximity to the Spanish colonies.

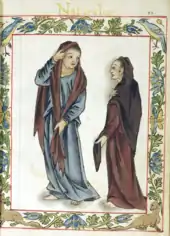

People who lived outside Manila, Cebu and the major Spanish posts were classified as such: 'Naturales' were Catholic Austronesians of the lowland and coastal towns. The un-Catholic Negritos and Austronesians who lived in the towns were classified as 'salvajes' (savages) or 'infieles' (the unfaithful). 'Remontados' (Spanish for 'situated in the mountains') and 'tulisanes' (bandits) were indigenous Austronesians and Negritos who refused to live in towns and took to the hills, all of whom were considered to live outside the social order as Catholicism was a driving force in Spanish colonials everyday life, as well as determining social class in the colony. People of pure Spanish descent living in the Philippines who were born in Spanish America were classified as 'americanos'. Mestizos and africanos born in Spanish America living in the Philippines kept their legal classification as such, and usually came as indentured servants to the 'americanos'. The Philippine-born children of 'americanos' were classified as 'Ins'. The Philippine-born children of mestizos and Africanos from Spanish America were classified based on patrilineal descent.

The term negrito was coined by the Spaniards based on their appearance. The word 'negrito' would be misinterpreted and used by future European scholars as an ethnoracial term in and of itself. Both Christianized negritos who lived in the colony and un-Christianized negritos who lived in tribes outside the colony were classified as 'negritos'. Christianized negritos who lived in Manila were not allowed to enter Intramuros and lived in areas designated for indios.

A person of mixed Negrito and Austronesian ancestry were classified based on patrilineal descent; the father's ancestry determined a child's legal classification. If the father was 'negrito' and the mother was 'India' (Austronesian), the child was classified as 'negrito'. If the father was 'indio' and the mother was 'negrita', the child was classified as 'indio'. Persons of Negrito descent were viewed as being outside the social order as they usually lived in tribes outside the colony and resisted conversion to Christianity.

This legal system of racial classification based on patrilineal descent had no parallel anywhere in the Spanish-ruled colonies in the Americas. In general, a son born of a sangley male and an indio or mestizo de sangley female was classified as mestizo de sangley; all subsequent male descendants were mestizos de sangley regardless of whether they married an India or a mestiza de sangley. A daughter born in such a manner, however, acquired the legal classification of her husband, i.e., she became an India if she married an indio but remained a mestiza de sangley if she married a mestizo de sangley or a sangley. In this way, a chino mestizo male descendant of a paternal sangley ancestor never lost his legal status as a mestizo de sangley no matter how little percentage of Chinese blood he had in his veins or how many generations had passed since his first Chinese ancestor; he was thus a mestizo de sangley in perpetuity.

However, a 'mestiza de sangley' who married a blanco ('Filipino', 'mestizo de español', 'peninsular', or 'americano') kept her status as 'mestiza de sangley'. But her children were classified as tornatrás. An 'India' who married a blanco also kept her status as India, but her children were classified as mestizo de español. A mestiza de español who married another blanco would keep her status as mestiza, but her status will never change from mestiza de español if she married a mestizo de español, Filipino, or peninsular. In contrast, a mestizo (de sangley or español) man's status stayed the same regardless of whom he married. If a mestizo (de sangley or español) married a filipina (woman of pure Spanish descent), she would lose her status as a 'filipina' and would acquire the legal status of her husband and become a mestiza de español or sangley. If a 'filipina' married an 'indio', her legal status would change to 'India', despite being of pure Spanish descent.

The social stratification system based on class that continues to this day in the country had its beginnings in the Spanish colonial area with a discriminating caste system.[102]

The Spanish colonizers reserved the term Filipino to refer to Spaniards born in the Philippines. The use of the term was later extended to include Spanish and Chinese mestizos, or those born of mixed Chinese-indio or Spanish-indio descent. Late in the 19th century, José Rizal popularized the use of the term Filipino to refer to all those born in the Philippines, including the Indios.[103] When ordered to sign the notification of his death sentence, which described him as a Chinese mestizo, Rizal refused. He went to his death saying that he was indio puro.[104][103]

The Spanish caste system based on race was abolished after the Philippines' independence from Spain in 1898, and the word 'Filipino' expanded to include the entire population of the Philippines regardless of racial ancestry.

Origins and genetic studies

.png.webp)

The aboriginal settlers of the Philippines were primarily Negrito groups. Negritos comprise a small minority of the nation's overall population.

The majority population of Filipinos are Austronesians, a linguistic and genetic group whose historical ties lay in maritime Southeast Asia, but through ancient migrations can be found as indigenous peoples stretching as far east as the Pacific islands and as far west as Madagascar off the coast of Africa.[106][107] The current predominant theory on Austronesian expansion holds that Austronesians settled the Philippine islands through successive southward and eastward seaborne migrations from the Neolithic Austronesian populations of Taiwan.[108]

Other hypotheses have also been put forward based on linguistic, archeological, and genetic studies. These include an origin from mainland South China (linking them to the Liangzhu culture and the Tapengkeng culture, later displaced or assimilated by the expansion of Sino-Tibetan peoples);[109][110] an in situ origin from the Sundaland continental shelf prior to the sea level rise at the end of the last glacial period (c. 10,000 BC);[111][112] or a combination of the two (the Nusantao Maritime Trading and Communication Network hypothesis) which advocates cultural diffusion rather than a series of linear migrations.[113]

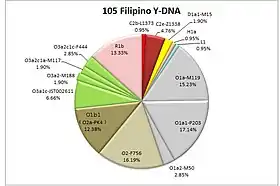

Y-DNA haplogroups

The most frequently occurring Y-DNA haplogroups among modern Filipinos are haplogroup O1a-M119, which has been found with maximal frequency among the indigenous peoples of Nias, the Mentawai Islands, and Taiwan, and Haplogroup O2-M122, which is found with high frequency in many populations of East Asia, Southeast Asia, and Polynesia. In particular, the type of O2-M122 that is found frequently in Filipinos, O-P164(xM134), is also found frequently in other Austronesian populations.[114][115] Trejaut et al. 2014 found O2a2b-P164(xO2a2b1-M134) in 26/146 = 17.8% of a pool of samples of Filipinos (4/8 = 50% Mindanao, 7/31 = 22.6% Visayas, 10/55 = 18.2% South Luzon, 1/6 = 17% North Luzon, 2/22 = 9.1% unknown Philippines, 2/24 = 8.3% Ivatan). The distributions of other subclades of O2-M122 in the Philippines were sporadic, but it may be noted that O2a1c-JST002611 was observed in 6/24 = 25% of a sample of Ivatan and 1/31 = 3.2% of a sample from the Visayas. A total of 45/146 = 30.8% of the sampled Filipinos were found to belong to Haplogroup O2-M122.[114] Haplogroup O1a-M119 is also commonly found among Filipinos (25/146 = 17.1% O1a-M119(xO1a1a-P203, O1a2-M50), 20/146 = 13.7% O1a1a-P203, 17/146 = 11.6% O1a2-M50, 62/146 = 42.5% O1a-M119 total according to Trejaut et al. 2014) and is shared with other Austronesian-speaking populations, especially those in Taiwan, western Indonesia, and Madagascar.[107][116]

From Latin America

There was migration of a military nature from Latin-America (Mexico and Peru) to the Philippines, composed of varying races (Amerindian, Mestizo and Castizo) as described by Stephanie J. Mawson in her book "Convicts or Conquistadores? Spanish Soldiers in the Seventeenth-Century Pacific".[117] Also, in her dissertation paper called, ‘Between Loyalty and Disobedience: The Limits of Spanish Domination in the Seventeenth Century Pacific’, she recorded an accumulated amount of 16,500 soldier-settlers sent to the Philippines from Latin-America during the 1600s.[118] These 16,500 Latinos sent to the Philippines supplemented a population of only 667,612 people.[119] After the 16th century, the colonial period saw the influx of genetic influence from other populations. This is evidenced by the presence of a small percentage of the Y-DNA Haplogroup R1b present among the population of the Philippines. DNA studies vary as to how small these lineages are. A year 2001 study conducted by Stanford University Asia-Pacific Research Center stated that only 3.6% of the Philippine population had European Y-DNA. According to another genetic study done by the University of California San Francisco, they discovered that a more "modest" amount of European genetic ancestry was found among some respondents who self-identified as Filipinos.[120] Practicing forensic anthropology, while exhuming cranial bones in several Philippine cemeteries, researcher Matthew C. Go estimated that 7% of the mean amount, among the samples exhumed, have attribution to European descent.[121]

From Europe / Spain

A 2015, Y-DNA compilation by the Genetics Company Applied Biosystems, using samples taken from all over the Philippines, resulted in a 13.33% frequency of the European/Spanish Y-DNA R1b which was likely taken from Latin-American soldiers who settled in the Philippines who had Spanish fathers and Amerindian mothers.[122]

Overall

A research paper, which claims to be a useful aid to biological anthropology, published in the "Journal of Forensic Anthropology", collating contemporary Anthropological data showed that the percentage of Filipino bodies who were sampled from the University of the Philippines, that were curated to be representative of Filipinos, that's phenotypically classified as Asian (East, South and Southeast Asian) is 72.7%, Hispanic (Spanish-Amerindian Mestizo, Latin American, or Spanish-Malay Mestizo) is at 12.7%, Indigenous American (Native American) at 7.3%, African at 4.5%, and European at 2.7%.[123]

From Japan

There are also Japanese people, which include escaped Christians (Kirishitan) who fled the persecutions of Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu which the Spanish empire in the Philippines had offered asylum from to form part of the Japanese settlement in the Philippines.[124]

During the American colonial era in the Philippines, the number of Japanese laborers working in plantations rose so high that in the 20th century, Davao City soon became dubbed as a Ko Nippon Koku ("Little Japan" in Japanese)[125] with a Japanese school, a Shinto shrine, and a diplomatic mission from Japan. There is even a popular restaurant called "The Japanese Tunnel", which includes an actual tunnel made by the Japanese in time of the war.[126]

There are also Japanese people, which include escaped Christians (Kirishitan) who fled the persecutions of Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu which the Spanish empire in the Philippines had offered asylum from.[271] The descendants of mixed-race couples are known as Tisoy.[272]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of Japanese traders also migrated to the Philippines and assimilated into the local population.[92] Around 28–30% of Filipinos have Chinese ancestry.

From India

The Indian Mitochondrial DNA hapolgroups, M52'58 and M52a are also present in the Philippines suggesting that there was Indian migration to the archipelago starting from the 5th Century AD.[127]

Also, according to a Y-DNA compilation by the DNA company Applied Biosystems, they calculated an estimated 1% frequency of the South Asian Y-DNA "H1a" in the Philippines. Thus translating to about 1,011,864 Filipinos having full or partial Indian descent, not including other Filipinos in the Philippines and Filipinos abroad whose DNA (Y-DNA) have not been analyzed.[128]

From Arabia

According to Philippine ambassador to Jordan, Junever M. Mahilum-West, in 2016, an estimated 2 percent of the population of the Philippines, about 2.2 million people, could claim partial Arab ancestry.[129]

Dental morphology

Dental morphology provides clues to prehistoric migration patterns of the Philippines, with Sinodont dental patterns occurring in East Asia, Central Asia, North Asia, and the Americas. Sundadont patterns occur in Southeast Asia as well as the bulk of Oceania.[130] Filipinos exhibit Sundadonty,[130][131] and are regarded as having a more generalised dental morphology and having a longer ancestry than its offspring, Sinodonty.

Historic reports

Published in 1849, The Catalogo Alfabetico de Apellidos contains 141 pages of surnames with both Spanish and indigenous roots.

Authored by Spanish Governor-General Narciso Claveria y Zaldua and Domingo Abella, the catalog was created in response to the Decree of November 21, 1849, which gave every Filipino a surname from the book. The decree in the Philippines was created to fulfill a Spanish colonial decree that sought to address colonial subjects who did not have a last name. This explains why a number of Filipinos without Spanish blood share the same surnames as many Spaniards today.

In relation to this, a population survey conducted by German ethnographer Fedor Jagor concluded that 1/3rd of Luzon which holds half of the Philippines' population had varying degrees of Spanish and Latin American ancestry.[132]

Current Immigration

Studies during 2015 recorded around 220,000 to 600,000 American citizens living in the country.[133] In 2016 there were 250,000 Filipino Amerasians across Angeles, Manila, Clark and Olongapo, who are faced with a long and laborious visa entry process obstructing the possibility of immigration to the US.[134]

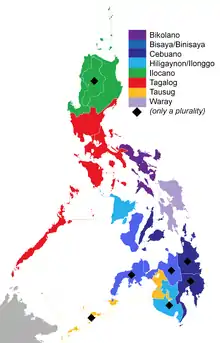

Languages

Austronesian languages have been spoken in the Philippines for thousands of years. According to a 2014 study by Mark Donohue of the Australian National University and Tim Denham of Monash University, there is no linguistic evidence for an orderly north-to-south dispersal of the Austronesian languages from Taiwan through the Philippines and into Island Southeast Asia (ISEA).[111] Many adopted words from Sanskrit and Tamil were incorporated during the strong wave of Indian (Hindu-Buddhist) cultural influence starting from the 5th century BC, in common with its Southeast Asian neighbors. Chinese languages were also commonly spoken among the traders of the archipelago. However, with the advent of Islam, Arabic and Persian soon came to supplant Sanskrit and Tamil as holy languages. Starting in the second half of the 16th century, Spanish was the official language of the country for the more than three centuries that the islands were governed through Mexico City on behalf of the Spanish Empire. The variant of Spanish used was Mexican-Spanish, which also included much vocabulary of Nahuatl (Aztec) origin. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Spanish was the preferred language among Ilustrados and educated Filipinos in general. Significant agreements exist, however, on the extent Spanish use beyond that. It has been argued that the Philippines were less hispanized than Canaries and America, with Spanish only being adopted by the ruling class involved in civil and judicial administration and culture. Spanish was the language of only approximately ten percent of the Philippine population when Spanish rule ended in 1898.[135] As a lingua franca or creole language of Filipinos, major languages of the country like Chavacano, Cebuano, Tagalog, Kapampangan, Pangasinan, Bicolano, Hiligaynon, and Ilocano assimilated many different words and expressions from Castilian Spanish.

Chavacano is the only Spanish-based creole language in Asia. Its vocabulary is 90 percent Spanish, and the remaining 10 percent is a mixture of predominantly Portuguese, Nahuatl (Mexican Indian), Hiligaynon, and some English. Chavacano is considered by the Instituto Cervantes to be a Spanish-based language.[136]

In sharp contrast, another view is that the ratio of the population which spoke Spanish as their mother tongue in the last decade of Spanish rule was 10% or 14%.[137] An additional 60% is said to have spoken Spanish as a second language until World War II, but this is also disputed as to whether this percentage spoke "kitchen Spanish", which was used as marketplace lingua compared to those who were actual fluent Spanish speakers.[137]

In 1863 a Spanish decree introduced universal education, creating free public schooling in Spanish, yet it was never implemented, even before the advent of American annexation.[138] It was also the language of the Philippine Revolution, and the 1899 Malolos Constitution proclaimed it as the "official language" of the First Philippine Republic, albeit a temporary official language. Spanish continued to be the predominant lingua franca used in the islands by the elite class before and during the American colonial regime. Following the American occupation of the Philippines and the imposition of English, the overall use of Spanish declined gradually, especially after the 1940s.

According to Ethnologue, there are about 180 languages spoken in the Philippines.[139] The 1987 Constitution of the Philippines imposed the Filipino language.[140][141] as the national language and designates it, along with English, as one of the official languages. Regional languages are designated as auxiliary official languages. The constitution also provides that Spanish and Arabic shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis.[142]

Other Philippine languages in the country with at least 1,000,000 native and indigenous speakers include Cebuano, Ilocano, Hiligaynon, Waray, Central Bikol, Kapampangan, Pangasinan, Chavacano (Spanish-based creole), Albay Bikol, Maranao, Maguindanao, Kinaray-a, Tausug, Surigaonon, Masbateño, Aklanon and Ibanag. The 28-letter modern Filipino alphabet, adopted in 1987, is the official writing system. In addition, each ethnicity's language has their own writing scripts and set of alphabets, many of which are no longer used.[143]

Religion

According to National Statistics Office (NSO) as of 2010, over 92% of the population were Christians, with 80.6% professing Roman Catholicism.[144] The latter was introduced by the Spanish beginning in 1565, and during their 300-year colonization of the islands, they managed to convert a vast majority of Filipinos, resulting in the Philippines becoming the largest Catholic country in Asia. There are also large groups of Protestant denominations, which either grew or were founded following the disestablishment of the Catholic Church during the American Colonial period. The Iglesia ni Cristo is currently the single largest church whose headquarters is in the Philippines, followed by United Church of Christ in the Philippines. The Iglesia Filipina Independiente (also known as the Aglipayan Church) was an earlier development, and is a national church directly resulting from the 1898 Philippine Revolution. Other Christian groups such as the Victory Church,[145] Jesus Miracle Crusade, Mormonism, Orthodoxy, and the Jehovah's Witnesses have a visible presence in the country.

The second largest religion in the country is Islam, estimated in 2014 to account for 5% to 8% of the population.[146] Islam in the Philippines is mostly concentrated in southwestern Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago which, though part of the Philippines, are very close to the neighboring Islamic countries of Malaysia and Indonesia. The Muslims call themselves Moros, a Spanish word that refers to the Moors (albeit the two groups have little cultural connection other than Islam).

Historically, ancient Filipinos held animist religions that were influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism, which were brought by traders from neighbouring Asian states. These indigenous Philippine folk religions continue to be present among the populace, with some communities, such as the Aeta, Igorot, and Lumad, having some strong adherents and some who mix beliefs originating from the indigenous religions with beliefs from Christianity or Islam.[147][148]

As of 2013, religious groups together constituting less than five percent of the population included Sikhism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Seventh-day Adventists, United Church of Christ, United Methodists, the Episcopal Church in the Philippines, Assemblies of God, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), and Philippine (Southern) Baptists; and the following domestically established churches: Iglesia ni Cristo (Church of Christ), Philippine Independent Church (Aglipayan), Members Church of God International, and The Kingdom of Jesus Christ, the Name Above Every Name. In addition, there are Lumad, who are indigenous peoples of various animistic and syncretic religions.[149]

Diaspora

There are currently more than 10 million Filipinos who live overseas. Filipinos form a minority ethnic group in the Americas, Europe, Oceania,[150][151] the Middle East, and other regions of the world.

There are an estimated four million Americans of Filipino ancestry in the United States, and more than 300,000 American citizens in the Philippines.[152] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, immigrants from the Philippines made up the second largest group after Mexico that sought family reunification.[153]

Filipinos make up over a third of the entire population of the Northern Marianas Islands, an American territory in the North Pacific Ocean, and a large proportion of the populations of Guam, Palau, the British Indian Ocean Territory, and Sabah.[151]

The demonym, Filipinx, is a gender-neutral term that is applied only to those of Filipino heritage in the diaspora. The term is not applied to and generally not accepted by Filipinos in the Philippines.[154][155]

See also

- Chinese Filipino

- Indian Filipino

- Spanish Filipino

- Pinoy

- Philippines

- Demographics of the Philippines

- Ethnic groups in the Philippines

- Philippine nationality law

- List of rulers of the Philippines

- List of Filipino athletes

- List of Filipino actors

- List of Filipino actresses

- List of Filipino comedians

- List of Filipino writers

- Overseas Filipinos

- Filipino cuisine

- Filipinos in Hawaii

- Filipinos in the New York metropolitan area

- Philippine music

- Philippine cinema

References

- "Urban Population in the Philippines (Results of the 2015 Census of Population), Release Date: 21 March 2019". Philippine Statistics Authority. (Total population 100,573,715 in 2015, per detail in TABLE 1 Population Enumerated in Various Censuses by Region: 1960 – 2015)

- Times, Asia (September 2, 2019). "Asia Times | Duterte's 'golden age' comes into clearer view | Article". Asia Times.

- "Remittances from Filipinos abroad reach 2.9 bln USD in August 2019 – Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com.

- Reported as Filipino alone or in any combination in "The Asian Population: 2010" (PDF). 2010 Census Briefs. census.gov.

- Stock Estimates of Filipinos Overseas 2007 Report Archived March 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Philippine Overseas Employment Administration. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- Statistics Canada (October 25, 2017). "Ethnic Origin, both sexes, age (total), Canada, 2016 Census – 25% Sample data". Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- "Know Your Diaspora: United Arab Emirates". Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- "No foreign workers' layoffs in Malaysia – INQUIRER.net, Philippine News for Filipinos". February 9, 2009. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- "2017年度末在留外国人確定値" (PDF). Japan. April 13, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2018.

- "Gulf News". www.gulfnews.com.

- "2016 Census QuickStats: Australia". www.censusdata.abs.gov.au.

- OFW Statistics, Philippines: Philippine Overseas Employment Administration, February 8, 2013, archived from the original on April 23, 2014, retrieved April 28, 2014

- "Demographic Balance and Resident Population by sex and citizenship on 31st December 2017". Istat.it. June 13, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "PGMA meets members of Filipino community in Spain". Gov.Ph. Retrieved July 1, 2006.

- 外僑居留-按國籍別 (Excel) (in Chinese). National Immigration Agency, Ministry of the Interior. February 28, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- Filipinos in South Korea. Korean Culture and Information Service (KOIS). Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- "Ethnic group profiles".

- "Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics". Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics.

- Amojelar, Darwin G. (April 26, 2013) Papua New Guinea thumbs down Philippine request for additional flights. InterAksyon.com. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- "CBS StatLine – Bevolking; generatie, geslacht, leeftijd en herkomstgroepering, 1 januari". Statline.cbs.nl. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- "Anzahl der Ausländer in Deutschland nach Herkunftsland (Stand: 31. Dezember 2014)".

- "Filipino Workers in Libya".

- Vapattanawong, Patama. ชาวต่างชาติในเมืองไทยเป็นใครบ้าง? (Foreigners in Thailand) (PDF). Institute for Population and Social Research – Mahidol University (in Thai). Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- "Macau Population Census". Census Bureau of Macau. May 2012. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- "pinoys-sweden-protest-impending-embassy-closure". ABS-CBN.com.

- "CSO Emigration" (PDF). Census Office Ireland. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- "Statistic Austria".

- "8 Folkemengde, etter norsk / utenlandsk statsborgerskap og landbakgrunn 1. januar 2009". Statistisk sentralbyra (Statistics Norway). Archived from the original on May 15, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- "President Aquino to meet Filipino community in Beijing". Ang Kalatas-Australia. August 30, 2011.

- "Backgrounder: Overseas Filipinos in Switzerland". Office of the Press Secretary. 2007. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

- Welcome to Embassy of Kazakhstan in Malaysia Website Archived November 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Kazembassy.org.my. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- Tan, Lesley (June 6, 2006). "A tale of two states". Cebu Daily News. Archived from the original on February 22, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- "Statistical Yearbook of Greece 2009 & 2010" (PDF). Hellenic Statistical Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- 11rv – Syntyperä ja taustamaa sukupuolen mukaan kunnittain, 1990–2018

- "No Filipino casualty in Turkey quake – DFA". GMA News. August 3, 2010.

- "Manila and Moscow Inch Closer to Labour Agreement". May 6, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- "Backgrounder: The Filipinos in Indonesia". Office of the Press Secretary. 2001. Archived from the original on April 15, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- People: Filipino, The Joshua Project

- "The Philippines To Sign Agreement with Morocco to Protect Filipino workers". Morocco World News.

- "Table 1.10; Household Population by Religious Affiliation and by Sex; 2010" (PDF). 2015 Philippine Statistical Yearbook: 1–30. October 2015. ISSN 0118-1564. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- "The 1987 Constitution of the Philippines". Official Gazette. Government of the Philippines. Preamble.

We, the sovereign Filipino people, ...

- "Philippines". Ethnologue Languages of the World. Ethnologue dot Com. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- "Filipino". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- Cruz, Elfren S. (July 29, 2018). "From indio to Filipino". PhilStar Global. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- Scott, William Henry (1994). "Introduction". Barangay: sixteenth-century Philippine culture and society. Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-971-550-135-4. OCLC 32930303.

But when it was necessary to distinguish the indios of the Philippines from those of the Americas, they were called Filipinos.

- Pedro Chirino (1604). Relacion de las islas Filippinas i de lo que in ellas an trabaiado los padres dae la Compania de Iesus. Del p. Pedro Chirino . por Estevan Paulino. pp. 38, 39, 52, 69.

- Chirino, Pedro (1604). "Cap. XXIII". Relacion de las islas Filippinas i de lo que in ellas an trabaiado los padres dae la Compania de Iesus. Del p. Pedro Chirino . (in Spanish). por Estevan Paulino. p. 75.

La primera i ultima diligencia que los Filipinos usavan en caso de enfermedad era, como avemos dicho, ofrecer algunos sacrificios a sus Anitos, o Diuatas, que eran sus dioses.

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-971-550-135-4.

Juan Francisco de San Antonio devotes a chapter of his 1738 Crónicas to "The letters, languages, and politeness of the Philippinos" (San Antonio 1738, 140), while Francisco Antolín argues in 1789 that "the ancient wealth of the Philippinos is much like that which the Igorots have at present" (Antolín 1789, 279).

- Scott, William Henry (1994). "Introduction". Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-971-550-135-4.

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: sixteenth-century Philippine culture and society. Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-971-550-135-4. OCLC 32930303.

Philippine-born Spaniards, however, often resented being called Filipinos by peninsulares, preferring the term hijos del país - children of the land.

- Ocampo, Ambeth R. (1995). Bonifacio's bolo. Anvil Pub. p. 21. ISBN 978-971-27-0418-5.

- Luis H. Francia (2013). "3. From Indio to Filipino : Emergence of a Nation, 1863-1898". History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos. ABRAMS. ISBN 978-1-4683-1545-5.

- Rolando M Gripaldo (2001). Filipino Philosophy: A Critical Bibliography (1774–1997). De La Salle University Press (e-book). p. 16 (note 1).

- https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1332278/filipinx-pinxy-among-new-nonbinary-words-in-online-dictionary

- https://www.esquiremag.ph/politics/opinion/leave-the-filipinx-kids-alone-a00304-20200907

- https://opinion.inquirer.net/133571/filipino-or-filipinx

- Welch, Michael Patrick (October 27, 2014). "NOLA Filipino History Stretches for Centuries". New Orleans & Me. New Orleans: WWNO. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- Aguilar, Filomeno V. (November 2012). "Manilamen and seafaring: engaging the maritime world beyond the Spanish realm". Journal of Global History. 7 (3): 364–388. doi:10.1017/S1740022812000241.

- Catholic Church. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (December 2001). Asian and Pacific Presence: Harmony in Faith. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-57455-449-6.

- Pang, Valerie Ooka; Cheng, Li-Rong Lilly (1999). Struggling to be heard: the Unmet Needs of Asian Pacific American Children. NetLibrary, Inc. p. 287. ISBN 0-585-07571-9. OCLC 1053003694.

- Holt, Thomas Cleveland; Green, Laurie B.; Wilson, Charles Reagan (October 21, 2013). "Pacific Worlds and the South". The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Race. 24: 120. doi:10.5860/choice.51-1252. ISSN 0009-4978.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Westbrook, Laura. "Mabuhay Pilipino! (Long Life!): Filipino Culture in Southeast Louisiana". Folklife in Louisiana. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- "Re-imagining Australia - Voices of Indigenous Australians of Filipino Descent". Western Australian Museum. Government of Western Australia. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- Ruiz-Wall, Deborah; Choo, Christine (2016). Re-imagining Australia: Voices of Indigenous Australians of Filipino Descent. Keeaira Press. ISBN 9780992324155.

- Wade, Lizzie (April 12, 2018). "Latin America's lost histories revealed in modern DNA". Science. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- Seijas, Tatiana (2014). Asian slaves in colonial Mexico : from chinos to Indians. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107477841.

- Henderson, Barney (August 3, 2010). "Archaeologists unearth 67000-year-old human bone in Philippines". The Daily Telegraph. UK.

- "Archaeology in the Philippines, the National Museum and an Emergent Filipino Nation". Wilhelm G. Solheim II Foundation for Philippine Archaeology, Inc.

- Scott 1984, pp. 14–15

- History.com Archived April 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Harold K. Voris (2000). "Maps of Pleistocene sea levels in Southeast Asia". Journal of Biogeography. 27 (5): 1153–1167. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00489.x.

- R. D. Gray (January 2009). "Language Phylogenies Reveal Expansion Pulses and Pauses in Pacific Settlement". Science. 323 (5913): 479–483. doi:10.1126/science.1166858. PMID 19164742. S2CID 29838345.

- Howells, William White (January 1, 1997). Getting Here: The Story of Human Evolution. Howells House. ISBN 9780929590165 – via Google Books.

- David Bulbeck; Pathmanathan Raghavan; Daniel Rayner (2006). "Races of Homo sapiens: if not in the southwest Pacific, then nowhere". World Archaeology. 38 (1): 109–132. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.534.3176. doi:10.1080/00438240600564987. ISSN 0043-8243. JSTOR 40023598. S2CID 84991420.

- "Background note: Philippines". U.S. Department of State Diplomacy in Action. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- "The People of the Philippines". Asian Info.

- Jocano 2001, pp. 34–56

- Mong Palatino (February 27, 2013). "Are Filipinos Malays?". The Diplomat. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- "About Pasay – History: Kingdom of Namayan". Pasay City Government website. City Government of Pasay. Archived from the original on November 20, 2007. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- Huerta, Felix, de (1865). Estado Geografico, Topografico, Estadistico, Historico-Religioso de la Santa y Apostolica Provincia de San Gregorio Magno. Binondo: Imprenta de M. Sanchez y Compañia.

- Remains of ancient barangays in many parts of Iloilo testify to the antiquity and richness of these pre-colonial settlements. Pre-Hispanic burial grounds are found in many towns of Iloilo. These burial grounds contained antique porcelain burial jars and coffins made of hard wood, where the dead were put to rest with abundance of gold, crystal beads, Chinese potteries, and golden masks. These Philippine national treasures are sheltered in Museo de Iloilo and in the collections of many Ilongo old families. Early Spanish colonizers took note of the ancient civilizations in Iloilo and their organized social structure ruled by nobilities. In the late 16th century, Fray Gaspar de San Agustin in his chronicles about the ancient settlements in Panay says: "También fundó convento el Padre Fray Martin de Rada en Araut- que ahora se llama el convento de Dumangas- con la advocación de nuestro Padre San Agustín ... Está fundado este pueblo casi a los fines del río de Halaur, que naciendo en unos altos montes en el centro de esta isla (Panay) ... Es el pueblo muy hermoso, ameno y muy lleno de palmares de cocos. Antiguamente era el emporio y corte de la más lucida nobleza de toda aquella isla." Gaspar de San Agustin, O.S.A., Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1565–1615), Manuel Merino, O.S.A., ed., Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas: Madrid 1975, pp. 374–375.

- "Arab and native intermarriage in Austronesian Asia". ColorQ World. Retrieved December 24, 2008.

- Philippine History by Maria Christine N. Halili. "Chapter 3: Precolonial Philippines" (Published by Rex Bookstore; Manila, Sampaloc St. Year 2004)

- The Kingdom of Namayan and Maytime Fiesta in Sta. Ana of new Manila, Traveler On Foot self-published l journal.

- Volume 5 of A study of the Eastern and Western Oceans (Japanese: 東西洋考) mentions that Luzon first sent tribute to Yongle Emperor in 1406.

- "Akeanon Online – Aton Guid Ra! – Aklan History Part 3 – Confederation of Madyaas". Akeanon.com. March 27, 2008. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- "Sultanate of Sulu, The Unconquered Kingdom". Archived from the original on December 1, 2008.

- Munoz, Paul Michel (2006). Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Editions Didier Millet. p. 171. ISBN 9799814155679.

- Background Note: Brunei Darussalam, U.S. State Department.

- "tribal groups". Mangyan Heritage Center. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008.

- Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-521-66370-0.

- Leupp, Gary P. (2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 52–3. ISBN 978-0-8264-6074-5.

- Tracy, Nicholas (1995). Manila Ransomed: The British Assault on Manila in the Seven Years War. University of Exeter Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-85989-426-5. ISBN 0-85989-426-6, ISBN 978-0-85989-426-5.

- Article 3 of the treaty specifically associated the $20 million payment with the transfer of the Philippines.

- "American Conquest of the Philippines – War and Consequences: Benevolent Assimilation and the 1899 PhilAm War". oovrag.com. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- Burdeos, Ray L. (2008). Filipinos in the U.S. Navy & Coast Guard During the Vietnam War. AuthorHouse. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4343-6141-7.

- Tucker, Spencer (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 478. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Burdeos 2008, p. 14

- "The Philippines – A History of Resistance and Assimilation". voices.cla.umn.edu. Archived from the original on February 8, 2006. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- "Women and children, militarism, and human rights: International Women's Working Conference – Off Our Backs – Find Articles at BNET.com". Archived from the original on February 3, 2009.

- "200,000–250,000 or More Military Filipino Amerasians Alive Today in Republic of the Philippines according to USA-RP Joint Research Paper Finding" (PDF). Amerasian Research Network, Ltd. (Press release). November 5, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

Kutschera, P.C.; Caputi, Marie A. (October 2012). "The Case for Categorization of Military Filipino Amerasians as Diaspora" (PDF). 9TH International Conference On the Philippines, Michigan State University, E. Lansing, MI. Retrieved July 11, 2016. - WHITE, LYNN T., III. (2018). PHILIPPINE POLITICS : possibilities and problems in a localist democracy. ROUTLEDGE. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-138-49233-2. OCLC 1013594469.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Owen, Norman G. (2014). Routledge Handbook of Southeast Asian History. Routledge. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-135-01878-8.

- Delmendo, Sharon (2005). The Star-entangled Banner: One Hundred Years of America in the Philippines. UP Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-971-542-484-4.

- Chambers, Geoff (2013). "Genetics and the Origins of the Polynesians". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences, 20 Volume Set. eLS. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0020808.pub2. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza; Alberto Piazza; Paolo Menozzi; Joanna Mountain (1988). "Reconstruction of human evolution: Bringing together genetic, archaeological, and linguistic data". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 (16): 6002–6006. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.16.6002. PMC 281893. PMID 3166138.

- Capelli, Cristian; James F. Wilson, Martin Richards, Michael P. H. Stumpf, Fiona Gratrix, Stephen Oppenheimer, Peter Underhill, Vincenzo L. Pascali, Tsang-Ming Ko, David B. Goldstein1 (2001). "A Predominantly Indigenous Paternal Heritage for the Austronesian-speaking Peoples of Insular Southeast Asia and Oceania" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 432–443. doi:10.1086/318205. PMC 1235276. PMID 11170891. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 14, 2010. Retrieved June 24, 2007.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Stephen J. Marshall, Adele L. H. Whyte, J. Frances Hamilton, and Geoffrey K. Chambers1 (2005). "Austronesian prehistory and Polynesian genetics: A molecular view of human migration across the Pacific" (PDF). New Zealand Science Review. 62 (3): 75–80. ISSN 0028-8667. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2012.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Albert Min-Shan Ko; Chung-Yu Chen; Qiaomei Fu; Frederick Delfin; Mingkun Li; Hung-Lin Chiu; Mark Stoneking; Ying-Chin Ko (2014). "Early Austronesians: Into and Out Of Taiwan". American Journal of Human Genetics. 94 (3): 426–436. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.02.003. PMC 3951936. PMID 24607387.

- Chuan-Kun Ho (2002). "Rethinking the Origins of Taiwan Austronesians" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Symposium of Anthropological Studies at Fudan University: 17–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 18, 2015.

- Mark Donohue; Tim Denham (2010). "Farming and Language in Island Southeast Asia". Current Anthropology. 51 (2): 223–256. doi:10.1086/650991. S2CID 4815693.

- "New DNA evidence overturns population migration theory in Island Southeast Asia". Phys.org. May 23, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- Wilhelm G. Solheim II (2002). "The Pre-Sa Huynh-Kalanay Pottery of Taiwan and Southeast Asia". Hukay. 13: 39–66.

- Trejaut, Jean A; Poloni, Estella S; Yen, Ju-Chen; Lai, Ying-Hui; Loo, Jun-Hun; Lee, Chien-Liang; He, Chun-Lin; Lin, Marie (2014). "Taiwan Y-chromosomal DNA variation and its relationship with Island Southeast Asia". BMC Genetics. 15: 77. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-15-77. PMC 4083334. PMID 24965575.

- Karafet, Tatiana M.; Hallmark, Brian; Cox, Murray P.; et al. (2010). "Major East–West Division Underlies Y Chromosome Stratification across Indonesia". Mol. Biol. Evol. 27 (8): 1833–1844. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq063. PMID 20207712.

- Chang JG, Ko YC, Lee JC, Chang SJ, Liu TC, Shih MC, Peng CT (2002). "Molecular analysis of mutations and polymorphisms of the Lewis secretor type alpha(1,2)-fucosyltransferase gene reveals that Taiwanese aborigines are of Austronesian derivation". J. Hum. Genet. 47 (2): 60–5. doi:10.1007/s100380200001. PMID 11916003.

- Mawson, Stephanie J. (June 15, 2016). "Convicts or Conquistadores? Spanish Soldiers in the Seventeenth-Century Pacific". Past & Present. Oxford Academic. 232: 87–125. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtw008. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- Stephanie Mawson, ‘Between Loyalty and Disobedience: The Limits of Spanish Domination in the Seventeenth Century Pacific’ (Univ. of Sydney M.Phil. thesis, 2014), appendix 3.

- The Unlucky Country: The Republic of the Philippines in the 21St Century By Duncan Alexander McKenzie (page xii)

- *Institute for Human Genetics, University of California San Francisco (2015). "Self-identified East Asian nationalities correlated with genetic clustering, consistent with extensive endogamy. Individuals of mixed East Asian-European genetic ancestry were easily identified; we also observed a modest amount of European genetic ancestry in individuals self-identified as Filipinos" (PDF). Genetics Online: 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 1, 2015.

- Go, Matthew C. (January 15, 2018). "An Admixture Approach to Trihybrid Ancestry Variation in the Philippines with Implications for Forensic Anthropology". Human Biology. 232 (3): 178. doi:10.13110/humanbiology.90.3.01. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

Filipinos appear considerably admixed with respect to the other Asian population samples, carrying on average less Asian ancestry (71%) than our Korean (99%), Japanese (96%), Thai (93%), and Vietnamese (84%) reference samples. We also revealed substructure in our Filipino sample, showing that the patterns of ancestry vary within the Philippines—that is, between the four diffferently sourced Filipino samples. Mean estimates of Asian (76%) and European (7%) ancestry are greatest for the cemetery sample of forensic signifijicance from Manila.

- With a sample population of 105 Filipinos, the company of Applied Biosystems, analyses the Y-DNA of the average Filipino.

- Go MC, Jones AR, Algee-Hewitt B, Dudzik B, Hughes C (2019). "Classification Trends among Contemporary Filipino Crania Using Fordisc 3.1". Human Biology. University of Florida Press. 2 (4): 1–11. doi:10.5744/fa.2019.1005. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

[Page 1] ABSTRACT: Filipinos represent a significant contemporary demographic group globally, yet they are underrepresented in the forensic anthropological literature. Given the complex population history of the Philippines, it is important to ensure that traditional methods for assessing the biological profile are appropriate when applied to these peoples. Here we analyze the classification trends of a modern Filipino sample (n = 110) when using the Fordisc 3.1 (FD3) software. We hypothesize that Filipinos represent an admixed population drawn largely from Asian and marginally from European parental gene pools, such that FD3 will classify these individuals morphometrically into reference samples that reflect a range of European admixture, in quantities from small to large. Our results show the greatest classification into Asian reference groups (72.7%), followed by Hispanic (12.7%), Indigenous American (7.3%), African (4.5%), and European (2.7%) groups included in FD3. This general pattern did not change between males and females. Moreover, replacing the raw craniometric values with their shape variables did not significantly alter the trends already observed. These classification trends for Filipino crania provide useful information for casework interpretation in forensic laboratory practice. Our findings can help biological anthropologists to better understand the evolutionary, population historical, and statistical reasons for FD3-generated classifications. The results of our studyindicate that ancestry estimation in forensic anthropology would benefit from population-focused research that gives consideration to histories of colonialism and periods of admixture.

- Terpstra, Nicholas (May 17, 2019). Global Reformations: Transforming Early Modern Religions, Societies, and Cultures. ISBN 9780429678257.

- "PHL: The country they love to hate". businessmirror.com.ph. January 7, 2015.

- "A Little Tokyo Rooted in the Philippines". Pacific Citizen. Philippines. April 2007. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008.

- Delfin, Fredercik (June 12, 2013). "Complete mtDNA genomes of Filipino ethnolinguistic groups: a melting pot of recent and ancient lineages in the Asia-Pacific regio". European Journal of Human Genetics. 22 (2): 228–237. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2013.122. PMC 3895641. PMID 23756438.

Indian influence and possibly haplogroups M52'58 and M52a were brought to the Philippines as early as the fifth century AD. However, Indian influence through these trade empires were indirect and mainly commercial; moreover, other Southeast Asian groups served as filters that diluted and/or enriched any Indian influence that reached the Philippines

- With a sample population of 105 Filipinos, the company of Applied Biosystems, analysed the Y-DNA of average Filipinos and it is discovered that about 0.95% of the samples have the Y-DNA Haplotype "H1a", which is most common in South Asia and had spread to the Philippines via precolonial Indian missionaries who spread Hinduism and established Indic Rajahnates like Cebu and Butuan.

- Rawashdeh, Saeb (October 11, 2016). "Arab world's ancient links to Philippines forged through trade, migration and Islam — ambassador". The Jordan Times. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

In the case of the Philippines, the ancient Hadrami migration found its way from Islamised areas in the south towards Sulu, the southwestern archipelagic region of the Philippines,” she said, adding that the Hadramis settled in Cotabato, Maguindao, Zamboanga, Davao and Bukidnon. An estimated 2 per cent of Filipinos can claim Arab ancestry, the ambassador noted.

- Henke, Winfried; Tattersall, Ian; Hardt, Thorolf (2007). Handbook of Paleoanthropology: Vol I:Principles, Methods and Approaches Vol II:Primate Evolution and Human Origins Vol III:Phylogeny of Hominids. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1903. ISBN 978-3-540-32474-4.

- George Richard Scott; Christy G. Turner (2000). The Anthropology of Modern Human Teeth: Dental Morphology and Its Variation in Recent Human Populations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 177, 179, 283-284. ISBN 978-0-521-78453-5.

- Jagor, Fëdor, et al. (1870). The Former Philippines thru Foreign Eyes

- Cooper, Matthew (November 15, 2013). "Why the Philippines Is America's Forgotten Colony". National Journal. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

c. At the same time, person-to-person contacts are widespread: Some 600,000 Americans live in the Philippines and there are 3 million Filipino-Americans, many of whom are devoting themselves to typhoon relief.

- "200,000–250,000 or More Military Filipino Amerasians Alive Today in Republic of the Philippines according to USA-RP Joint Research Paper Finding" (PDF). Amerasian Research Network, Ltd. (Press release). November 5, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

Kutschera, P.C.; Caputi, Marie A. (October 2012). "The Case for Categorization of Military Filipino Amerasians as Diaspora" (PDF). 9th International Conference On the Philippines, Michigan State University, E. Lansing, MI. Retrieved July 11, 2016. - Penny & Penny 2002, pp. 29–30

- "El Torno Chabacano". Instituto Cervantes. Instituto Cervantes.

- Gómez Rivera, Guillermo (2005). "Estadisticas: El idioma español en Filipinas". Retrieved May 2, 2010. "Los censos norteamericanos de 1903 y 1905, dicen de soslayo que los Hispano-hablantes de este archipiélago nunca han rebasado, en su número, a más del diez por ciento (10%) de la población durante la última década de los mil ochocientos (1800s). Esto quiere decir que 900,000 Filipinos, el diez porciento de los dados nueve millones citados por el Fray Manuel Arellano Remondo, tenían al idioma español como su primera y única lengua." (Emphasis added.) The same author writes: "Por otro lado, unos recientes estudios por el Dr. Rafael Rodríguez Ponga señalan, sin embargo, que los Filipinos de habla española, al liquidarse la presencia peninsular en este archipiélago, llegaban al catorce (14%) por ciento de la población de la década 1891–1900. Es decir, el 14% de una población de nueve millones (9,000,000), que serían un millón (1,260,000) y dos cientos sesenta mil de Filipinos que eran primordialmente de habla hispana. (Vea Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos, enero de 2003)". (La persecución del uso oficial del idioma español en Filipinas. Retrieved July 8, 2010.)

- "Philippines – EDUCATION".

- "Languages of the Philippines". Ethnologue.

- Thompson, Roger M. (2003). "3. Nationalism and the rise of the hegemonic Imposition of Tagalog 1936–1973". Filipino English and Taglish. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-90-272-4891-6., ISBN 90-272-4891-5, ISBN 978-90-272-4891-6.

- Andrew Gonzalez (1998). "The Language Planning Situation in the Philippines" (PDF). Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 19 (5, 6): 487–488. doi:10.1080/01434639808666365. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- Article XIV, Section 6, The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines.

- Linda Trinh Võ; Rick Bonus (2002). Contemporary Asian American communities: intersections and divergences. Temple University Press. pp. 96, 100. ISBN 978-1-56639-938-8.

- "Table 1.10; Household Population by Religious Affiliation and by Sex; 2010" (PDF). 2015 Philippine Statistical Yearbook: 1–30. October 2015. ISSN 0118-1564. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- Victory, Outreach. "Victory Outreach". Victory Outreach. Victory Outreach. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- Philippines. 2013 Report on International Religious Freedom (Report). United States Department of State. July 28, 2014. SECTION I. RELIGIOUS DEMOGRAPHY.

The 2000 survey states that Islam is the largest minority religion, constituting approximately 5 percent of the population. A 2012 estimate by the National Commission on Muslim Filipinos (NCMF), however, states that there are 10.7 million Muslims, which is approximately 11 percent of the total population.

- Stephen K. Hislop (1971). "Anitism: a survey of religious beliefs native to the Philippines" (PDF). Asian Studies. 9 (2): 144–156.

- McCoy, A. W. (1982). Baylan: Animist Religion and Philippine Peasant Ideology. University of San Carlos Publications.

- "Philippines". 2013 Report on International Religious Freedom. U.S. Department of State. July 28, 2014.

- "National Summary Tables". Australian Bureau of Statistics. June 6, 2001. Retrieved June 6, 2001.

- "Population Composition: Asian-born Australians". Australian Bureau of Statistics. June 6, 2001. Retrieved June 6, 2001.

- "Background Note: Philippines". Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. United States Department of State. June 3, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- Castles, Stephen and Mark J. Miller. (July 2009). "Migration in the Asia-Pacific Region Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine". Migration Information Source. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- https://www.esquiremag.ph/politics/opinion/leave-the-filipinx-kids-alone-a00304-20200907

- https://opinion.inquirer.net/133571/filipino-or-filipinx

- Penny, Ralph; Penny, Ralph John (2002). A history of the Spanish language (22nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01184-6.

Publications

- Peter Bellwood (July 1991). "The Austronesian Dispersal and the Origin of Languages". Scientific American. 265 (1): 88–93. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0791-88.

- Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James; Tryon, Darrell (1995). The Austronesians: Historical and comparative perspectives. Department of Anthropology, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-7315-2132-6.

- Peter Bellwood (1998). "Taiwan and the Prehistory of the Austronesians-speaking Peoples". Review of Archaeology. 18: 39–48.

- Peter Bellwood; Alicia Sánchez-Mazas (June 2005). "Human Migrations in Continental East Asia and Taiwan: Genetic, Linguistic, and Archaeological Evidence". Current Anthropology. 46 (3): 480–485. doi:10.1086/430018. S2CID 145495386.

- David Blundell. "Austronesian Disperal". Newsletter of Chinese Ethnology. 35: 1–26.

- Robert Blust (1985). "The Austronesian Homeland: A Linguistic Perspective". Asian Perspectives. 20: 46–67.