Massagetae

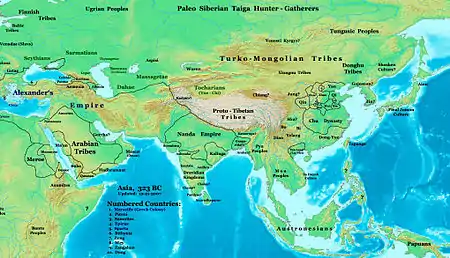

The Massagetae, or Massageteans,[1] (Greek: Μασσαγέται (Massagétai), Iranian: *Masyaka-tā)[2][3] were an ancient Eastern Iranian nomadic tribal confederation,[4][5][6][7] who inhabited the steppes of Central Asia, north-east of the Caspian Sea in modern Turkmenistan, western Uzbekistan, and southern Kazakhstan. They belonged to the Saka people,[2][3] and were part of the wider Scythian cultures,[8]

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

According to Greek and Roman scholars, the Massagetae were neighboured by the Aspasioi (possibly the Aśvaka) to the north, the Scythians and the Dahae to the west, and the Issedones (possibly the Wusun) to the east. Sogdia lay to the south.[9]

Name

The exonym "Massagetae" (Greek: Massagétai) is the Grecized plural form of the personal name Masságēs.[3] The Iranologist Rüdiger Schmitt notes that although the original name of the Massagetae is unattested, it appears that the most plausible etymon is Iranian *Masyaka-tā.[2][3] *Masyaka-tā is the plural form, containing the East Iranian suffix *-tā, which is reflected in Greek -tai.[3] The singular form is *Masi̯a-ka- and is composed of Iranian *-ka- and *masi̯a- "fish", derived from Young Avestan masiia- (cognate with Vedic mátsya-).[3] The name literally means "concerned with fish", or "fisherman."[2][3] This corresponds with the remark by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus (1.216.3) that "they live on their livestock and fish."[2] Schmitt notes that objections to this reasoning, based on the assumption that instead of masi̯a- a derivation from Iranian *kapa- "fish" (compare Ossetian kæf) would be expected, is "not decisive".[3] Schmitt states that any other interpretatations on the origin of the original Iranian name of the Massagetae are "linguistically unacceptable".[3]

History

The Massagetae are known primarily from the writings of Herodotus who described the Massagetae as living on a sizeable portion of the great plain east of the Caspian Sea.[10] He several times refers to them as living "beyond the River Araxes", which flows through the Caucasus and into the west Caspian.[11] Scholars have offered various explanations for this anomaly. For example, Herodotus may have confused two or more rivers, as he had limited and frequently indirect knowledge of geography.[12]

According to Herodotus, the Massagetae attacked the Scythians, who in response crossed the river Araxes and invaded the country of the Cimmerians, who fled into Anatolia due to the Scythian invasion, with the Scythians pursuing them and eventually invading the Medes.[13]

Death of Cyrus

Many Greek historians recorded that the Massagetae queen Tomyris "defeated and killed" Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II of Persia), founder of the Achaemenid Empire, during his invasion and attempted conquest of her country. Herodotus, who lived from approximately 484 to 425 BC, is the earliest of the classical writers to give an account of this conflict, writing almost one hundred years later, and Tomyris's history was well known and became legendary. Strabo, Polyaenus, Cassiodorus, and Jordanes also wrote of Tomyris, in De origine actibusque Getarum ("The origin and deeds of the Goths/Getae").[14]

Cyrus and Croesus offered the Massagetae a treaty of peace via the marriage of Cyrus to the Massagetae queen Tomyris. Tomyris turned down the offer, and sent a strongly-worded letter to Cyrus warning him against any advancement. However, in an attempt to bring peace and order to the northern territories of the growing Persian empire, Cyrus made an advance towards Jaxartes with the Persian army in circa 530 B.C.E. Following the advice of Croesus, Cyrus left behind a small group of Persians and set up a banquet, intending for the Massagetians to attack and slaughter this small pocket of Persian resistance and gorge themselves on the food and wine. Among the Massagetians was Tomyris' son and the general of her army, Spargapises, who ate and drank himself to inebriation and satiation.[15][16]

According to the accounts of Greek historians, Cyrus was victorious in his initial assault on the Massagetae. His advisers suggested laying a trap for the pursuing Scythians: the Persians left behind them an apparently abandoned camp, containing a rich supply of wine. The pastoral Scythians were not used to drinking wine—"their favored intoxicants were Hasheesh with fermented mare's milk"[17]—and they drank themselves into a stupor (with the alcohol deliberately left behind by Cyrus). The Persians returned while their opponents were incapacitated and attacked the Massagetian force, defeating the Massagetae forces, and capturing Spargapises. Of the one third of the Massagetae forces that fought, there were more captured than killed.

When Spargapises realized his army's blunder and his own mistake, he begged Cyrus for freedom. Cyrus responded by ordering that he should be set free. Once free, Spargapises committed suicide by falling on his own sword in despair at his humiliation and defeat.[18][19][15] Spargapises's behavior, including his intoxication, suicide, and lack of maturity when compared to that of Cyrus the Great, has led some scholars to term him adulescentulum filium.[19]

Tomyris sent a message to Cyrus denouncing his treachery, and with all her forces, challenged him to a second battle. In the fight that ensued, the Massagetae got the upper hand, and the Persians were defeated with high casualties. According to Herodotus, Cyrus was killed and Tomyris had his corpse beheaded and then crucified,[20] and shoved his head into a wineskin filled with human blood. She was reportedly quoted as saying, "I warned you that I would quench your thirst for blood, and so I shall"[21][22] (Hdt 1.214)[18] Xenophon, on the other hand, says that Cyrus died peacefully in his bed,[23] and a number of other sources report different causes of death.

Culture

The original language of the Massagetae is little-known. While it appears to have had similarities to the Eastern Iranian languages (Spargapises's name is of Scythian origin, and his name and the name of the Agathyrsi king Spargapeithes are variants of the same name, and are cognates with the Avestan name Sparəγa-paēsa.[24]), these may have resulted from interactions with neighbouring peoples, such as language contact or sprachbund-type assimilation.

Possible connections to other ancient peoples

Ancient writers

Herodotus stated the Massagetae were a great and warlike nation, dwelling beyond the river Araxes and that they are regarded as a Scythian race.[25]

Ammianus Marcellinus considered the Alans to be the former Massagetae.[26] At the close of the 4th century CE, Claudian (the court poet of Emperor Honorius and Stilicho) wrote of Alans and Massagetae in the same breath: "the Massagetes who cruelly wound their horses that they may drink their blood, the Alans who break the ice and drink the waters of Maeotis' lake" (In Rufinem).

Medieval writers

Procopius writes in History of the Wars Book III: The Vandalic War:[27] "the Massagetae whom they now call Huns" (XI. 37.), "there was a certain man among the Massagetae, well gifted with courage and strength of body, the leader of a few men; this man had the privilege handed down from his fathers and ancestors to be the first in all the Hunnic armies to attack the enemy" (XVIII. 54.).

Evagrius Scholasticus (Ecclesiastical History. Book 3. Ch. II.): "and in Thrace, by the inroads of the Huns, formerly known by the name of Massagetae, who crossed the Ister without opposition".[28]

A 9th century work by Rabanus Maurus, De Universo, states: "The Massagetae are in origin from the tribe of the Scythians, and are called Massagetae, as if heavy, that is, strong Getae."[29][30] In Central Asian languages such as Middle Persian and Avestan, the prefix massa means "great", "heavy", or "strong".[31]

Modern writers

Some authors, such as Alexander Cunningham, James P. Mallory, Victor H. Mair, and Edgar Knobloch have proposed relating the Massagetae to the Gutians of 2000 BC Mesopotamia, and/or a people known in ancient China as the "Da Yuezhi" or "Great Yuezhi" (who founded the Kushan Empire in South Asia). Mallory and Mair suggest that Da Yuezhi may at one time have been pronounced d'ad-ngiwat-tieg, connecting them to the Massagetae.[32][33][34] These theories are not widely accepted, however.

Many scholars have suggested that the Massagetae were related to the Getae of ancient Eastern Europe.[35]

Tadeusz Sulimirski notes that the Sacae also invaded parts of Northern India.[36] Weer Rajendra Rishi, an Indian linguist[37] has identified linguistic affinities between Indian and Central Asian languages, which further lends credence to the possibility of historical Sacae influence in Northern India.[31][36]

According to Guive Mirfendereski at the Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies (CAIS), the Massagetae are synonymous with the Sakā haumavargā of South Asian historiography.

Rüdiger Schmitt notes Ptolemy's conflicting reports concerning the Massagetae.[3] First, localizing them near Margiana, then later Ptolemy calls them a tribe of the Saka in the vicinity of the Hindu Kush and Karakorum.[3] Schmitt also notes that Byzantine authors used the word "Massagetae" as an antiquated term for Huns, Turks, Tatars and other related peoples, "what has no relevance, however, for ancient times".[3]

See also

Footnotes

- Engels, Donald W. (1978). Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army. California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04272-7.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2021). "Massagetae". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Schmitt 2018.

- Karasulas, Antony. Mounted Archers Of The Steppe 600 BC-AD 1300 (Elite). Osprey Publishing, 2004, ISBN 184176809X, p. 7.

- Wilcox, Peter. Rome's Enemies: Parthians and Sassanids. Osprey Publishing, 1986, ISBN 0-85045-688-6, p. 9.

- Gershevitch, I.; Fisher, William Bayne; Boyle, John Andrew; Yarshater, Ehsan; Frye, Richard Nelson (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780521200912.

- Grousset, René. The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press, 1989, ISBN 0-8135-1304-9, p. 547.

- Unterländer, Martina (March 3, 2017). "Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe". Nature Communications. 8: 14615. doi:10.1038/ncomms14615. PMC 5337992. PMID 28256537.

During the first millennium BCE, nomadic people spread over the Eurasian Steppe from the Altai Mountains over the northern Black Sea area as far as the Carpathian Basin... Greek and Persian historians of the 1st millennium BCE chronicle the existence of the Massagetae and Sauromatians, and later, the Sarmatians and Sacae: cultures possessing artefacts similar to those found in classical Scythian monuments, such as weapons, horse harnesses and a distinctive ‘Animal Style' artistic tradition. Accordingly, these groups are often assigned to the Scythian culture...

- Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel

- Herodotus, The Histories, 1.204.

- Herodotus, The Histories, 1.202.

- Herodotus, The Histories, translation by Robin Waterfield, with notes by Carolyn Deward (1998), p. 613, notes on 1.201-16.

- Herodotus, The Histories, 4.11.

- "The Origin And Deeds Of The Goths". ucalgary.ca. 1997-04-22. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- Robert B. Strassler (2009). The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories. Random House Digital, Inc. pp. 113–4.

- Hutton Webster (1913). Readings in ancient history. D.C. Heath & Co. p. 19.

Spargapises.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, and Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World. New York, Overlook Duckworth, 2003; p. 158.

- Halsall, Paul (August 1998). "Herodotus: Queen Tomyris of the Massagetai and the Defeat of the Persians under Cyrus". Internet Ancient History Sourcebook. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- Deborah Levine Gera (1997). Warrior women: the anonymous Tractatus de mulieribus. BRILL. pp. 199–200.

- Mayor, pp. 157–9.

- Herodotus Book One (205)-(214)

- "More Women Rulers". Women in World History Curriculum. 1996–2010. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- Xenophon, Cyropaedia VII. 7; M.A. Dandamaev, "Cyrus II", in Encyclopaedia Iranica, p. 250. See also H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg "Cyropaedia", in Encyclopaedia Iranica, on the reliability of Xenophon's account.

- Walter Hinz: Altiranisches Sprachgut der Nebenüberleiferung. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1975, p. 226.

- Herodotus, The Histories, 1.201.

- Ammianus Marcellinus: "iuxtaque Massagetae Halani et Sargetae"; "per Albanos et Massagetas, quos Alanos nunc appellamus"; "Halanos pervenit, veteres Massagetas".

- Procopius: History of the Wars. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/History_of_the_Wars/Book_III

- Ecclesiastical History. Book 3. http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/evagrius_3_book3.htm

- Maurus, Rabanus (1864). Migne, Jacques Paul (ed.). De universo. Paris.

The Massagetae are in origin from the tribe of the Scythians, and are called Massagetae, as if heavy, that is, strong Getae.

- Dhillon, Balbir Singh (1994). History and study of the Jats: with reference to Sikhs, Scythians, Alans, Sarmatians, Goths, and Jutes (illustrated ed.). Canada: Beta Publishers. p. 8. ISBN 1-895603-02-1.

- Rishi, Weer Rajendra (1982). India & Russia: linguistic & cultural affinity. Roma. p. 95.

- Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000), The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, London: Thames & Hudson. pages 98-99

- John F. Haskins (2016). Pazyrik - The Valley of the Frozen Tombs. Read Books. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4733-5279-7.

- THE STRONGEST TRIBE, Yu. A. Zuev, page 33: "Massagets of the earliest ancient authors... are the Yuezhis of the Chinese sources"

- Leake, Jane Acomb (1967). The Geats of Beowulf: a study in the geographical mythology of the Middle Ages (illustrated ed.). University of Wisconsin Press. p. 68. ISBN 9780598177209.

- Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970). The Sarmatians. Volume 73 of Ancient peoples and places. New York: Praeger. pp. 113–114.

The evidence of both the ancient authors and the archaeological remains point to a massive migration of Sacian (Sakas)/Massagetan tribes from the Syr Daria Delta (Central Asia) by the middle of the second century B.C. Some of the Syr Darian tribes; they also invaded North India.

- Indian Institute of Romani Studies Archived 2013-01-08 at Archive.today

Sources

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2018). "MASSAGETAE". Encyclopaedia Iranica.