Gravity assist

In orbital mechanics and aerospace engineering, a gravitational slingshot, gravity assist maneuver, or swing-by is the use of the relative movement (e.g. orbit around the Sun) and gravity of a planet or other astronomical object to alter the path and speed of a spacecraft, typically to save propellant and reduce expense.

| Part of a series on |

| Astrodynamics |

|---|

|

Gravity assistance can be used to accelerate a spacecraft, that is, to increase or decrease its speed or redirect its path. The "assist" is provided by the motion of the gravitating body as it pulls on the spacecraft.[1] The gravity assist maneuver was first used in 1959 when the Soviet probe Luna 3 photographed the far side of Earth's Moon and it was used by interplanetary probes from Mariner 10 onwards, including the two Voyager probes' notable flybys of Jupiter and Saturn.

Explanation

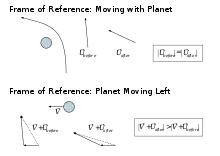

In the planet's frame of reference, the space probe leaves with the exact same speed at which it had arrived. But when observed in the reference frame of the Solar System (fixed to the Sun), the benefit of this maneuver becomes apparent. Here it can be seen how the probe gains speed by tapping energy from the speed of the planet as it orbits the Sun. (If the trajectory is designed to pass in front of the planet instead of behind it, the gravity assist can be used as a braking maneuver rather than accelerating.) Because the mass of the probe is many orders of magnitude smaller than that of the planet, while the result on the probe is quite significant, the deceleration reaction experienced by the planet, according to Newton's third law, is utterly imperceptible.

A gravity assist around a planet changes a spacecraft's velocity (relative to the Sun) by entering and leaving the gravitational sphere of influence of a planet. The spacecraft's speed increases as it approaches the planet and decreases while escaping its gravitational pull (which is approximately the same), but because the planet orbits the Sun the spacecraft is affected by this motion during the maneuver. To increase speed, the spacecraft flies with the movement of the planet, acquiring some of the planet's orbital energy in the process; to decrease speed, the spacecraft flies against the movement of the planet to transfer some of its own orbital energy to the planet - in both types of maneuver the energy transfer compared to the planet's total orbital energy is negligible. The sum of the kinetic energies of both bodies remains constant (see elastic collision). A slingshot maneuver can therefore be used to change the spaceship's trajectory and speed relative to the Sun.

A close terrestrial analogy is provided by a tennis ball bouncing off the front of a moving train. Imagine standing on a train platform, and throwing a ball at 30 km/h toward a train approaching at 50 km/h. The driver of the train sees the ball approaching at 80 km/h and then departing at 80 km/h after the ball bounces elastically off the front of the train. Because of the train's motion, however, that departure is at 130 km/h relative to the train platform; the ball has added twice the train's velocity to its own.

Translating this analogy into space: in the planet reference frame, the spaceship has a vertical velocity of v relative to the planet. After the slingshot occurs the spaceship is leaving on a course 90 degrees to that which it arrived on. It will still have a velocity of v, but in the horizontal direction.[2] In the Sun reference frame, the planet has a horizontal velocity of v, and by using the Pythagorean Theorem, the spaceship initially has a total velocity of √2v. After the spaceship leaves the planet, it will have a velocity of v + v = 2v, gaining around 0.6v.[2]

This oversimplified example is impossible to refine without additional details regarding the orbit, but if the spaceship travels in a path which forms a hyperbola, it can leave the planet in the opposite direction without firing its engine. This example is also one of many trajectories and gains of speed the spaceship can have.

This explanation might seem to violate the conservation of energy and momentum, apparently adding velocity to the spacecraft out of nothing, but the spacecraft's effects on the planet must also be taken into consideration to provide a complete picture of the mechanics involved. The linear momentum gained by the spaceship is equal in magnitude to that lost by the planet, so the spacecraft gains velocity and the planet loses velocity. However, the planet's enormous mass compared to the spacecraft makes the resulting change in its speed negligibly small even when compared to the orbital perturbations planets undergo due to interactions with other celestial bodies on astronomically short timescales. For example, one metric ton is a typical mass for an interplanetary space probe whereas Jupiter has a mass of almost 2 x 1024 metric tons. Therefore, a one-ton spacecraft passing Jupiter will theoretically cause the planet to lose approximately 5 x 10−25 km/s of orbital velocity for every km/s of velocity relative to the Sun gained by the spacecraft. For all practical purposes, since the effects on the planet are so slight (because planets are so much more massive than spacecraft) they can be ignored in the calculation.[3]

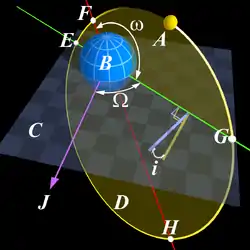

Realistic portrayals of encounters in space require the consideration of three dimensions. The same principles apply, only adding the planet's velocity to that of the spacecraft requires vector addition, as shown below.

Due to the reversibility of orbits, gravitational slingshots can also be used to reduce the speed of a spacecraft. Both Mariner 10 and MESSENGER performed this maneuver to reach Mercury.

If even more speed is needed than available from gravity assist alone, the most economical way to use a rocket burn is to do it near the periapsis (closest approach). A given rocket burn always provides the same change in velocity (Δv), but the change in kinetic energy is proportional to the vehicle's velocity at the time of the burn. So to get the most kinetic energy from the burn, the burn must occur at the vehicle's maximum velocity, at periapsis. Oberth effect describes this technique in more detail.

Derivation

The formulae for the gravitational assist can be derived from the familiar formulae for an elastic collision. Both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved, so for bodies with masses and , and velocities and before collision, and and after collision. The momentum before and after the collision is expressed by:[4]

The kinetic energy is expressed by:[4]

These equations may be solved to find when are known:[5]

In the case of a spacecraft flying past a planet, the mass of the spacecraft () is negligible compared with that of a planet () (), so this reduces to:

Historical origins

In his paper "Тем кто будет читать, чтобы строить" (To those who will be reading [this paper] in order to build [an interplanetary rocket]),[6] published in 1938 but dated 1918–1919,[7] Yuri Kondratyuk suggested that a spacecraft traveling between two planets could be accelerated at the beginning and end of its trajectory by using the gravity of the two planets' moons. This part of his manuscript considering gravity-assists received no later development and it was not published until the 1960s.[8] In his 1925 paper "Проблема полета при помощи реактивных аппаратов: межпланетные полеты" [Problems of flight by jet propulsion: interplanetary flights],[9] Friedrich Zander showed a deep understanding of physics behind the concept of gravity-assist and its potential for the interplanetary exploration of the solar system. This is even more outstanding when considering that other great astrodynamicists of the time never considered gravity-assists, e.g. Guido von Pirquet and Walter Hohmann.[10]

The first to calculate an interplanetary journey considering multiple gravity-assists was the Italian engineer Gaetano Crocco.[11]

The gravity assist maneuver was first used in 1959 when the Soviet probe Luna 3 photographed the far side of Earth's Moon. The maneuver relied on research performed under the direction of Mstislav Keldysh at the Steklov Institute of Mathematics[12] by, amongst others, Vsevolod Alexandrovich Egorov.[13][14]

Purpose

A spacecraft traveling from Earth to an inner planet will increase its relative speed because it is falling toward the Sun, and a spacecraft traveling from Earth to an outer planet will decrease its speed because it is leaving the vicinity of the Sun.

Although the orbital speed of an inner planet is greater than that of the Earth, a spacecraft traveling to an inner planet, even at the minimum speed needed to reach it, is still accelerated by the Sun's gravity to a speed notably greater than the orbital speed of that destination planet. If the spacecraft's purpose is only to fly by the inner planet, then there is typically no need to slow the spacecraft. However, if the spacecraft is to be inserted into orbit about that inner planet, then there must be some way to slow it down.

Similarly, while the orbital speed of an outer planet is less than that of the Earth, a spacecraft leaving the Earth at the minimum speed needed to travel to some outer planet is slowed by the Sun's gravity to a speed far less than the orbital speed of that outer planet. Therefore, there must be some way to accelerate the spacecraft when it reaches that outer planet if it is to enter orbit about it. However, if the spacecraft is accelerated to more than the minimum required, less total propellant will be needed to enter orbit about the target planet. In addition, accelerating the spacecraft early in the flight reduces the travel time.

Rocket engines can certainly be used to increase and decrease the speed of the spacecraft. However, rocket thrust takes propellant, propellant has mass, and even a small change in velocity (known as Δv, or "delta-v", the delta symbol being used to represent a change and "v" signifying velocity) translates to a far larger requirement for propellant needed to escape Earth's gravity well. This is because not only must the primary-stage engines lift the extra propellant, they must also lift the extra propellant beyond that which is needed to lift that additional propellant. The liftoff mass requirement increases exponentially with an increase in the required delta-v of the spacecraft.

Because additional fuel is needed to lift fuel into space, space missions are designed with a tight propellant "budget", known as the "delta-v budget". The delta-v budget is in effect the total propellant that will be available after leaving the earth, for speeding up, slowing down, stabilization against external buffeting (by particles or other external effects), or direction changes, if it cannot acquire more propellant. The entire mission must be planned within that capability. Therefore, methods of speed and direction change that do not require fuel to be burned are advantageous, because they allow extra maneuvering capability and course enhancement, without spending fuel from the limited amount which has been carried into space. Gravity assist maneuvers can greatly change the speed of a spacecraft without expending propellant, and can save significant amounts of propellant, so they are a very common technique to save fuel.

Limits

The main practical limit to the use of a gravity assist maneuver is that planets and other large masses are seldom in the right places to enable a voyage to a particular destination. For example, the Voyager missions which started in the late 1970s were made possible by the "Grand Tour" alignment of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. A similar alignment will not occur again until the middle of the 22nd century. That is an extreme case, but even for less ambitious missions there are years when the planets are scattered in unsuitable parts of their orbits.

Another limitation is the atmosphere, if any, of the available planet. The closer the spacecraft can approach, the faster its periapsis speed as gravity accelerates the spacecraft, allowing for more kinetic energy to be gained from a rocket burn. However, if a spacecraft gets too deep into the atmosphere, the energy lost to drag can exceed that gained from the planet's gravity. On the other hand, the atmosphere can be used to accomplish aerobraking. There have also been theoretical proposals to use aerodynamic lift as the spacecraft flies through the atmosphere. This maneuver, called an aerogravity assist, could bend the trajectory through a larger angle than gravity alone, and hence increase the gain in energy.

Even in the case of an airless body, there is a limit to how close a spacecraft may approach. The magnitude of the achievable change in velocity depends on the spacecraft's approach velocity and the planet's escape velocity at the point of closest approach (limited by either the surface or the atmosphere.)

Interplanetary slingshots using the Sun itself are not possible because the Sun is at rest relative to the Solar System as a whole. However, thrusting when near the Sun has the same effect as the powered slingshot described as the Oberth effect. This has the potential to magnify a spacecraft's thrusting power enormously, but is limited by the spacecraft's ability to resist the heat.

An interstellar slingshot using the Sun is conceivable, involving for example an object coming from elsewhere in our galaxy and swinging past the Sun to boost its galactic travel. The energy and angular momentum would then come from the Sun's orbit around the Milky Way. This concept features prominently in Arthur C. Clarke's 1972 award-winning novel Rendezvous With Rama; his story concerns an interstellar spacecraft that uses the Sun to perform this sort of maneuver, and in the process alarms many nervous humans.

A rotating black hole might provide additional assistance, if its spin axis is aligned the right way. General relativity predicts that a large spinning mass produces frame-dragging—close to the object, space itself is dragged around in the direction of the spin. Any ordinary rotating object produces this effect. Although attempts to measure frame dragging about the Sun have produced no clear evidence, experiments performed by Gravity Probe B have detected frame-dragging effects caused by Earth.[15] General relativity predicts that a spinning black hole is surrounded by a region of space, called the ergosphere, within which standing still (with respect to the black hole's spin) is impossible, because space itself is dragged at the speed of light in the same direction as the black hole's spin. The Penrose process may offer a way to gain energy from the ergosphere, although it would require the spaceship to dump some "ballast" into the black hole, and the spaceship would have had to expend energy to carry the "ballast" to the black hole.

Tisserand parameter and gravity assists

The use of gravity assists is constrained by a conserved quantity called the Tisserand parameter (or invariant). This is an approximation to the Jacobi constant of the restricted three-body problem. Considering the case a comet orbiting the Sun and the effects a Jupiter encounter would have, Félix Tisserand showed that

will remain constant (where is the comet's semi-major axis, its eccentricity, its inclination, and is the semi-major axis of Jupiter). This applies when the comet is sufficiently far from Jupiter to have well-defined orbital elements and to the extent that Jupiter is much less massive than the Sun and on a circular orbit.

This quantity is conserved for any system of three objects, one of which has negligible mass, and another of which is of intermediate mass and on a circular orbit. Examples are the Sun, Earth and a spacecraft, or Saturn, Titan and the Cassini spacecraft (using the semi-major axis of the perturbing body instead of ). This imposes a constraint on how a gravity assist may be used to alter a spacecraft's orbit.

The Tisserand parameter will change if the spacecraft makes a propulsive maneuver or a gravity assist of some fourth object, which is one reason that many spacecraft frequently combine Earth and Venus (or Mars) gravity assists or also perform large deep space maneuvers.

Timeline of notable examples

Luna 3

The gravity assist maneuver was first used in 1959 when Luna 3 photographed the far side of Earth's Moon.

Pioneer 10

In December 1973, Pioneer 10 spacecraft was the first one to use the gravitational slingshot effect to reach escape velocity to leave Solar System.

Mariner 10

The Mariner 10 probe was the first spacecraft to use the gravitational slingshot effect to reach another planet, passing by Venus on 5 February 1974 on its way to becoming the first spacecraft to explore Mercury.

Voyager 1

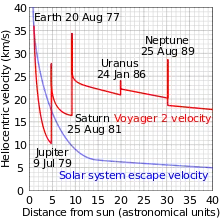

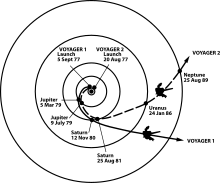

As of 21 July 2018, Voyager 1 is over 142.75 AU (21.36 billion km) from the Sun,[16] and is in interstellar space.[17] It gained the energy to escape the Sun's gravity completely by performing slingshot maneuvers around Jupiter and Saturn.[18]

Galileo

Galileo · Jupiter · Earth · Venus · 951 Gaspra · 243 Ida

The Galileo spacecraft was launched by NASA in 1989 aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis. Its original mission was designed to use a direct Hohmann transfer. However, Galileo's intended booster, the cryogenically fueled Centaur booster rocket was prohibited as a Shuttle "cargo" for safety considerations following the loss of Space Shuttle Challenger. With its substituted solid rocket upper stage, the IUS, which could not provide as much delta-v, Galileo did not ascend directly to Jupiter, but flew by Venus once and Earth twice in order to reach Jupiter in December 1995.

The Galileo engineering review speculated (but was never able to prove conclusively) that this longer flight time coupled with the stronger sunlight near Venus caused lubricant in Galileo's main antenna to fail, forcing the use of a much smaller backup antenna with a consequent lowering of data rate from the spacecraft.

Its subsequent tour of the Jovian moons also used numerous slingshot maneuvers with those moons to conserve fuel and maximize the number of encounters.

Ulysses

In 1990, NASA launched the ESA spacecraft Ulysses to study the polar regions of the Sun. All the planets orbit approximately in a plane aligned with the equator of the Sun. Thus, to enter an orbit passing over the poles of the Sun, the spacecraft would have to eliminate the 30 km/s speed it inherited from the Earth's orbit around the Sun and gain the speed needed to orbit the Sun in the pole-to-pole plane, tasks that are impossible with current spacecraft propulsion systems alone, making gravity assist maneuvers essential.

Accordingly, Ulysses was first sent toward Jupiter and aimed to arrive at a point in space just ahead and south of the planet. As it passed Jupiter, the probe fell through the planet's gravity field, exchanging momentum with the planet. The gravity assist maneuver bent the probe's trajectory northward relative to the Ecliptic Plane onto an orbit which passes over the poles of the Sun. By using this maneuver, Ulysses needed only enough propellant to send it to a point near Jupiter, which is well within current capability.

MESSENGER

The MESSENGER mission (launched in August 2004) made extensive use of gravity assists to slow its speed before orbiting Mercury. The MESSENGER mission included one flyby of Earth, two flybys of Venus, and three flybys of Mercury before finally arriving at Mercury in March 2011 with a velocity low enough to permit orbit insertion with available fuel. Although the flybys were primarily orbital maneuvers, each provided an opportunity for significant scientific observations.

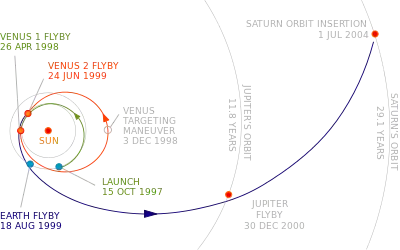

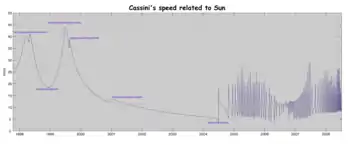

Cassini

The Cassini–Huygens spacecraft passed by Venus twice, then Earth, and finally Jupiter on the way to Saturn. The 6.7-year transit was slightly longer than the six years needed for a Hohmann transfer, but cut the extra velocity (delta-v) needed to about 2 km/s, so that the large and heavy Cassini probe was able to reach Saturn, which would not have been possible in a direct transfer even with the Titan IV, the largest launch vehicle available at the time. A Hohmann transfer to Saturn would require a total of 15.7 km/s delta-v (disregarding Earth's and Saturn's own gravity wells, and disregarding aerobraking), which is not within the capabilities of current launch vehicles and spacecraft propulsion systems.

After entering orbit around Saturn, the Cassini spacecraft used multiple Titan gravity assists to navigate through a complex orbital tour. A typical Titan encounter changed the spacecraft's velocity by 0.75 km/s, and the spacecraft made 127 Titan encounters. These encounters enabled an orbital tour with a wide range of periapsis and apoapsis distances, various alignments of the orbit with respect to the Sun, and orbital inclinations from 0° to 74°.

Rosetta

Rosetta · 67P/C-G · Earth · Mars · 21 Lutetia · 2867 Šteins

The Rosetta probe, launched in March 2004, used four gravity assist maneuvers (including one just 250 km from the surface of Mars) to accelerate throughout the inner Solar System. That enabled it to match the velocity of the 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko comet at the rendezvous point in August 2014.

Juno

The Juno spacecraft was launched on August 5, 2011 (UTC). The trajectory used a gravity assist speed boost from Earth, accomplished by an Earth flyby in October 2013, two years after its launch on August 5, 2011.[19] In that way Juno changed its orbit (and speed) toward its final goal, Jupiter, after only five years.

Parker Solar Probe

NASA's Parker Solar Probe mission, launched in 2018, will use multiple gravity assists at Venus to remove the Earth's angular momentum from the orbit to drop to a distance of 8.5 solar radii (5.9 Gm) from the Sun. Parker Solar Probe's mission will be the closest approach to the Sun by any space mission.

BepiColombo

BepiColombo is a joint mission of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to the planet Mercury. It was launched in 20 October 2018. It will use the gravity assist technique with Earth once, with Venus twice, and six times with Mercury. BepiColombo is named after Giuseppe (Bepi) Colombo who was a pioneer thinker with this way of maneuvers.

See also

- 3753 Cruithne, an asteroid which periodically has gravitational slingshot encounters with Earth

- Delta-v budget

- Low-energy transfer, a type of gravitational assist where a spacecraft is gravitationally snagged into orbit by a celestial body. This method is usually executed in the Earth-Moon system.

- Dynamical friction

- Flyby anomaly, an anomalous delta-v increase during gravity assists

- Gravitational keyhole

- Interplanetary Transport Network

- n-body problem

- New Horizons, a gravity-assisted mission (flying past Jupiter) that reached Pluto on 14 July 2015

- Pioneer 10

- Pioneer 11, a gravity-assisted mission (flying past Jupiter 1974-12-03) to reach Saturn in 1979

- Pioneer H, first Out-Of-The-Ecliptic mission (OOE) proposed, for Jupiter and solar (Sun) observations

- STEREO, a gravity-assisted mission which used Earth's Moon to eject two spacecraft from Earth's orbit into heliocentric orbit

References

- "Section 1: Environment, Chapter 4: Trajectories". Basics of Space Flight. NASA. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Gravity assist". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- Johnson, R. C. (January 2003). "The slingshot effect" (PDF). Durham University. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Serway, Raymond A. (5 March 2013). Physics for scientists and engineers with modern physics. Jewett, John W., Peroomian, Vahé. (Ninth ed.). Boston, MA. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-133-95405-7. OCLC 802321453.

- Serway, Raymond A. (5 March 2013). Physics for scientists and engineers with modern physics. Jewett, John W., Peroomian, Vahé. (Ninth ed.). Boston, MA. p. 258. ISBN 978-1-133-95405-7. OCLC 802321453.

- Kondratyuk's paper is included in the book: Mel'kumov, T. M., ed., Pionery Raketnoy Tekhniki [Pioneers of Rocketry: Selected Papers] (Moscow, U.S.S.R.: Institute for the History of Natural Science and Technology, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1964). An English translation of Kondratyuk's paper was made by NASA. See: NASA Technical Translation F-9285, pages 15-56 (1 November 1965).

- In 1938, when Kondratyuk submitted his manuscript "To whoever will read in order to build" for publication, he dated the manuscript 1918–1919, although it was apparent that the manuscript had been revised at various times. See page 49 of NASA Technical Translation F-9285 (1 November 1965).

- Negri, Rodolfo Batista; Prado, Antônio Fernando Bertachini de Alme (14 July 2020). "A historical review of the theory of gravity-assists in the pre-spaceflight era". Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering. 42 (8). doi:10.1007/s40430-020-02489-x. S2CID 220510617.

- Zander's 1925 paper, "Problems of flight by jet propulsion: interplanetary flights" was translated by NASA. See NASA Technical Translation F-147 (1964); specifically, Section 7: Flight Around a Planet's Satellite for Accelerating or Decelerating Spaceship, pages 290–292.

- Negri, Rodolfo Batista; Prado, Antônio Fernando Bertachini de Alme (14 July 2020). "A historical review of the theory of gravity-assists in the pre-spaceflight era". Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering. 42 (8). doi:10.1007/s40430-020-02489-x. S2CID 220510617.

- Negri, Rodolfo Batista; Prado, Antônio Fernando Bertachini de Alme (14 July 2020). "A historical review of the theory of gravity-assists in the pre-spaceflight era". Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering. 42 (8). doi:10.1007/s40430-020-02489-x. S2CID 220510617.

- Eneev, T.; Akim, E. "Mstislav Keldysh. Mechanics of the space flight" (in Russian). Keldysh Institute of Applied Mathematics.

- Egorov, Vsevolod Alexandrovich (September 1957). "Specific problems of a flight to the moon". Physics-Uspekhi. 63 (9): 73–117. doi:10.3367/UFNr.0063.195709f.0073.

- Rauschenbakh, Boris V.; Ovchinnikov, Michael Yu.; McKenna-Lawlor, Susan M. P. (2003). Essential Spaceflight Dynamics and Magnetospherics. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic. pp. 146–147. ISBN 0-306-48027-1.

- Everitt, C. W. F.; et al. (June 2011). "Gravity Probe B: Final Results of a Space Experiment to Test General Relativity". Physical Review Letters. 106 (22). 221101. arXiv:1105.3456. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106v1101E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.221101. PMID 21702590. S2CID 11878715.

- "Spacecraft escaping the Solar System". Heavens-Above. 21 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Interstellar Voyager". NASA. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- "A Gravity Assist Primer". Basics of Space Flight. NASA. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "NASA's Shuttle and Rocket Launch Schedule". NASA. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

External links

| Look up gravity assist in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Basics of Space Flight: A Gravity Assist Primer at NASA.gov

- Spaceflight and Spacecraft: Gravity Assist, discussion at Phy6.org

- "Gravitational Slingshot". MathPages.com.

- Double-ball drop experiment

- "Gravity-assist 'Slingshot', Background, principle, applications, Part 1 and 2", on EEWorldoneline.com