Haakon VII of Norway

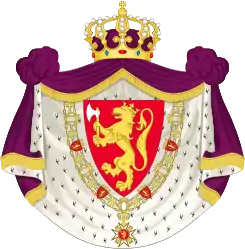

Haakon VII (Norwegian pronunciation: [ˈhòːkɔn]) (born Prince Carl of Denmark; 3 August 1872 – 21 September 1957) was the King of Norway from November 1905 until his death in September 1957.

| Haakon VII | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Haakon VII of Norway in 1906 | |||||

| King of Norway | |||||

| Reign | 18 November 1905 − 21 September 1957 | ||||

| Coronation | 22 June 1906 | ||||

| Predecessor | Oscar II | ||||

| Successor | Olav V | ||||

| Prime Ministers | |||||

| Born | Prince Carl of Denmark 3 August 1872 Charlottenlund Palace, Copenhagen, Denmark | ||||

| Died | 21 September 1957 (aged 85) Royal Palace, Oslo, Norway | ||||

| Burial | 1 October 1957 Akershus Castle, Oslo, Norway | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Olav V of Norway | ||||

| |||||

| House | Glücksburg | ||||

| Father | Frederick VIII of Denmark | ||||

| Mother | Louise of Sweden | ||||

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen as the son of the future Frederick VIII of Denmark and Louise of Sweden. Prince Carl was educated at the Royal Danish Naval Academy and served in the Royal Danish Navy. After the 1905 dissolution of the union between Sweden and Norway, Prince Carl was offered the Norwegian crown. Following a November plebiscite, he accepted the offer and was formally elected King of Norway by the Storting. He took the Old Norse name Haakon and ascended to the throne as Haakon VII, becoming the first independent Norwegian monarch since 1387.[1]

Norway was invaded by Nazi Germany in April 1940. Haakon rejected German demands to legitimise the Quisling regime's puppet government, and refused to abdicate after going into exile in Great Britain. As such, he played a pivotal role in uniting the Norwegian nation in its resistance to the invasion and the subsequent five-year-long occupation during the Second World War. He returned to Norway in June 1945 after the defeat of Germany.

He became King of Norway when his grandfather Christian IX was still reigning in Denmark, and before his father and elder brother became kings of Denmark. During his reign he saw his father, his elder brother Christian X, and his nephew Frederick IX ascend the throne of Denmark, in 1906, 1912, and 1947 respectively. Haakon died at the age of 85 in September 1957, after having reigned for nearly 52 years. He was succeeded by his only son, who ascended to the throne as Olav V.[2]

Family and early life

Prince Carl was born on 3 August 1872 at his parents' country residence, Charlottenlund Palace north of Copenhagen, during the reign of his paternal grandfather, King Christian IX.[3] He was the second son of Crown Prince Frederick of Denmark (the future King Frederick VIII), and his wife Louise of Sweden.[3] His father was the eldest son of King Christian IX and Louise of Hesse-Kassel, and his mother was the only daughter of King Charles XV of Sweden (who was also king of Norway as Charles IV), and Louise of the Netherlands. He was baptised at Charlottenlund Palace on 7 September 1872 by the Bishop of Zealand, Hans Lassen Martensen. He was baptised with the names Christian Frederik Carl Georg Valdemar Axel, and was known as Prince Carl (namesake of his maternal grandfather the King of Sweden-Norway).[3]

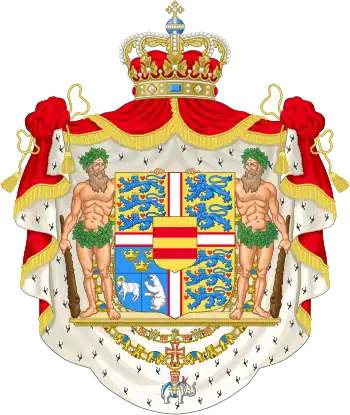

Prince Carl belonged to the Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg branch of the House of Oldenburg. The House of Oldenburg had been the Danish royal family since 1448; between 1536 and 1814 it also ruled Norway, which was then part of the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway. The house was originally from northern Germany, where the Glucksburg (Lyksborg) branch held their small fief. The family had permanent links with Norway beginning from the late Middle Ages. Several of his paternal ancestors had been kings of independent Norway (Haakon V of Norway, Christian I of Norway, Frederick I, Christian III, Frederick II, Christian IV, as well as Frederick III of Norway who integrated Norway into the Oldenburg state with Denmark, Schleswig and Holstein, after which it was not independent until 1814). Christian Frederick, who was King of Norway briefly in 1814, the first king of the Norwegian 1814 constitution and struggle for independence, was his great-granduncle.

Prince Carl was raised with his siblings in the royal household in Copenhagen, and grew up between his parents' residence in Copenhagen, the Frederick VIII's Palace, an 18th-century palace which forms part of the Amalienborg Palace complex in central Copenhagen, and their country residence, Charlottenlund Palace, located by the coastline of the Øresund strait north of the city. As a younger son of the Crown Prince, there was little expectation that Carl would become king. He was third in line to the throne, after his father and elder brother, Prince Christian. Carl was less than two years younger than Christian, and the two princes were confirmed together at Christiansborg Palace Chapel in 1887. Prince Carl was educated at the Royal Danish Naval Academy from 1889 to 1893, graduating as a second lieutenant in the Royal Danish Navy. In 1894 he was promoted to the rank of first lieutenant and remained in service with the Royal Danish Navy until 1905.[4]

Marriage

At Buckingham Palace on 22 July 1896,[5] Prince Carl married his first cousin Princess Maud of Wales, youngest daughter of the future King Edward VII of the United Kingdom and his wife, Princess Alexandra of Denmark, eldest daughter of King Christian IX and Princess Louise. Their son, Prince Alexander, the future Crown Prince Olav (and eventually king Olav V of Norway), was born on 2 July 1903.[5]

Accession to the Norwegian throne

Background and election

After the Union between Sweden and Norway was dissolved in 1905, a committee of the Norwegian government identified several princes of European royal houses as candidates for the Norwegian crown. Although Norway had legally had the status of an independent state since 1814, it had not had its own king since 1387. Gradually, Prince Carl became the leading candidate, largely because he was descended from independent Norwegian kings. He also had a son, providing an heir-apparent to the throne, and the fact that his wife, Princess Maud, was a member of the British Royal Family was viewed by many as an advantage to the newly independent Norwegian nation.[6]

The democratically minded Carl, aware that Norway was still debating whether to remain a kingdom or to switch instead to a republican system of government, was flattered by the Norwegian government's overtures, but he made his acceptance of the offer conditional on the holding of a referendum to show whether monarchy was the choice of the Norwegian people.

| Norwegian Royalty House of Oldenburg (Glücksburg branch) |

|---|

|

| Haakon VII |

|

| Olav V |

| Harald V |

|

After the referendum overwhelmingly confirmed by a 79 percent majority (259,563 votes for and 69,264 against) that Norwegians desired to retain a monarchy,[7] Prince Carl was formally offered the throne of Norway by the Storting (parliament) and was elected on 18 November 1905. When Carl accepted the offer that same evening (after the approval of his grandfather Christian IX of Denmark), he immediately endeared himself to his adopted country by taking the Old Norse name of Haakon, a name which had not been used by kings of Norway for over 500 years.[8] In so doing, he succeeded his maternal great-uncle, Oscar II of Sweden, who had abdicated the Norwegian throne in October following the agreement between Sweden and Norway on the terms of the separation of the union.

The new royal family of Norway left Denmark on the Danish royal yacht Dannebrog and sailed into Oslofjord. At Oscarsborg Fortress, they boarded the Norwegian naval ship Heimdal. After a three-day journey, they arrived in Kristiania (now Oslo) early on the morning of 25 November 1905. Two days later, Haakon took the oath as Norway's first independent king in 518 years. The coronation of Haakon and Maud took place in Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim on 22 June 1906.[5]

Reign

King Haakon gained much sympathy from the Norwegian people. He travelled extensively through Norway. Although the Constitution of Norway vests the King with considerable executive powers, in practice nearly all major governmental decisions were made by the Government (the Council of State) in his name. Haakon confined himself to non-partisan roles without interfering in politics, a practice continued by his son and grandson. However, his long rule gave him considerable moral authority as a symbol of the country's unity. The Norwegian explorer and Nobel Prize laureate Fridtjof Nansen became a friend of the Royal Family.

In 1927, the Labour Party became the largest party in parliament and early the following year Norway's first Labour Party government rose to power. The Labour Party was considered to be "revolutionary" by many and the deputy prime minister at the time advised against appointing Christopher Hornsrud as Prime Minister. Haakon, however, refused to abandon parliamentary convention and asked Hornsrud to form a new government. In response to some of his detractors he stated, "I am also the King of the Communists" (Norwegian: "Jeg er også kommunistenes konge").[9]

Crown Prince Olav married his cousin Princess Märtha of Sweden on 21 March 1929. She was the daughter of Haakon's sister Ingeborg and Prince Carl, Duke of Västergötland. Olav and Märtha had three children: Ragnhild (1930–2012), Astrid (born 1932) and Harald (born 1937), who was to become king in 1991.

Queen Maud died unexpectedly while visiting the United Kingdom on 20 November 1938.[10]

Resistance during World War II

The German invasion

Norway was invaded by the naval and air forces of Nazi Germany during the early hours of 9 April 1940. The German naval detachment sent to capture Oslo was opposed by Oscarsborg Fortress. The fortress fired at the invaders, sinking the heavy cruiser Blücher and damaging the heavy cruiser Lützow, with heavy German losses that included many of the armed forces, Gestapo agents, and administrative personnel who were to have occupied the Norwegian capital. This led to the withdrawal of the rest of the German flotilla, preventing the invaders' planned dawn occupation of Oslo. The German delay in occupying Oslo, along with swift action by the President of the Storting, C. J. Hambro, created the opportunity for the Norwegian Royal Family, the cabinet, and most of the 150 members of the Storting (parliament) to make a hasty departure from the capital by special train.

The Storting first convened at Hamar the same afternoon, but with the rapid advance of German troops, the group moved on to Elverum. The assembled Storting unanimously enacted a resolution, the so-called Elverum Authorization, granting the cabinet full powers to protect the country until such time as the Storting could meet again.

The next day, Curt Bräuer, the German Ambassador to Norway, demanded a meeting with Haakon. The German diplomat called on Haakon to accept Adolf Hitler's demands to end all resistance and appoint Vidkun Quisling as prime minister. Quisling, the leader of Norway's fascist party, the Nasjonal Samling, had declared himself prime minister hours earlier in Oslo as head of what would be a German puppet government; had Haakon formally appointed him, it would effectively have given legal sanction to the invasion. Bräuer suggested that Haakon follow the example of the Danish government and his brother, Christian X, which had surrendered almost immediately after the previous day's invasion, and threatened Norway with harsh reprisals if it did not surrender. Haakon told Bräuer that he could not make the decision himself, but could only act on the advice of the Government.

In a meeting in Nybergsund, the King reported the German ultimatum to the cabinet sitting as a council of state. Haakon told the cabinet:

I am deeply affected by the responsibility laid on me if the German demand is rejected. The responsibility for the calamities that will befall people and country is indeed so grave that I dread to take it. It rests with the government to decide, but my position is clear.

For my part I cannot accept the German demands. It would conflict with all that I have considered to be my duty as King of Norway since I came to this country nearly thirty-five years ago.[11]

Haakon went on to say that he could not appoint Quisling as prime minister, since he knew neither the people nor the Storting had confidence in him. However, if the cabinet felt otherwise, the King said he would abdicate so as not to stand in the way of the Government's decision.

Nils Hjelmtveit, Minister of Church and Education, later wrote:

This made a great impression on us all. More clearly than ever before, we could see the man behind the words; the king who had drawn a line for himself and his task, a line from which he could not deviate. We had through the five years [in government] learned to respect and appreciate our king, and now, through his words, he came to us as a great man, just and forceful; a leader in these fatal times to our country.[12]

Inspired by Haakon's stand, the Government unanimously advised him not to appoint any government headed by Quisling. Within hours, it telephoned its refusal to Bräuer. That night, NRK broadcast the government's rejection of the German demands to the Norwegian people. In that same broadcast, the Government announced that it would resist the German invasion as long as possible, and expressed their confidence that Norwegians would lend their support to the cause.

Government in exile

The following morning, 11 April 1940, in an attempt to wipe out Norway's unyielding king and government, Luftwaffe bombers attacked Nybergsund, destroying the small town where the Government was staying. Neutral Sweden was only 16 miles away, but the Swedish government decided it would "detain and incarcerate" King Haakon if he crossed their border (which Haakon never forgave).[13] The Norwegian king and his ministers took refuge in the snow-covered woods and escaped harm, continuing farther north through the mountains toward Molde on Norway's west coast. As the British forces in the area lost ground under Luftwaffe bombardment, the King and his party were taken aboard the British cruiser HMS Glasgow at Molde and conveyed a further 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) north to Tromsø, where a provisional capital was established on 1 May. Haakon and Crown Prince Olav took up residence in a forest cabin in Målselvdalen valley in inner Troms County, where they would stay until evacuation to the United Kingdom.

The Allies had a fairly secure hold over northern Norway until late May. The situation was dramatically altered, however, by their deteriorating situation in the Battle of France. With the Germans rapidly overrunning France, the Allied high command decided that the forces in northern Norway should be withdrawn. The Royal Family and Norwegian Government were evacuated from Tromsø on 7 June aboard HMS Devonshire with a total of 461 passengers. This evacuation became extremely costly for the Royal Navy when the German warships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau attacked and sank the nearby aircraft carrier HMS Glorious with its escorting destroyers HMS Acasta and HMS Ardent. Devonshire did not rebroadcast the enemy sighting report made by Glorious as it could not disclose its position by breaking radio silence. No other British ship received the sighting report, and 1,519 British officers and men and three warships were lost. Devonshire arrived safely in London and King Haakon and his Cabinet set up a Norwegian government in exile in the British capital.[14][15]

Initially, King Haakon and Crown Prince Olav were guests at Buckingham Palace, but at the start of the London Blitz in September 1940, they moved to Bowdown House in Berkshire. The construction of the adjacent RAF Greenham Common airfield in March 1942 prompted another move to Foliejon Park in Winkfield, near Windsor, in Berkshire, where they remained until the liberation of Norway.[16] The King's official residence was the Norwegian Legation at 10 Palace Green, Kensington, which became the seat of the Norwegian government in exile. Here Haakon attended weekly Cabinet meetings and worked on the speeches which were regularly broadcast by radio to Norway by the BBC World Service. These broadcasts helped to cement Haakon's position as an important national symbol to the Norwegian resistance.[17] Many broadcasts were made from Saint Olav's Norwegian Church in Rotherhithe, where the Royal Family were regular worshippers.[18]

Meanwhile, Hitler had appointed Josef Terboven as Reichskommissar for Norway. On Hitler's orders, Terboven attempted to coerce the Storting to depose the King; the Storting declined, citing constitutional principles. A subsequent ultimatum was made by the Germans, threatening to intern all Norwegians of military age in German concentration camps.[19] With this threat looming, the Storting's representatives in Oslo wrote to their monarch on 27 June, asking him to abdicate. The King declined, politely replying that the Storting was acting under duress. The King gave his answer on 3 July, and proclaimed it on BBC radio on 8 July.[20]

After one further German attempt in September to force the Storting to depose Haakon failed, Terboven finally decreed that the Royal Family had "forfeited their right to return" and dissolved the democratic political parties.[21]

During Norway's five years under German control, many Norwegians surreptitiously wore clothing or jewellery made from coins bearing Haakon's "H7" monogram as symbols of resistance to the German occupation and of solidarity with their exiled King and Government, just as many people in Denmark wore his brother's monogram on a pin. The King's monogram was also painted and otherwise reproduced on various surfaces as a show of resistance to the occupation.[22]

After the end of the war, Haakon and the Norwegian Royal Family returned to Norway aboard the cruiser HMS Norfolk, arriving with the First Cruiser Squadron to cheering crowds in Oslo on 7 June 1945,[23] exactly five years after they had been evacuated from Tromsø.[24]

Post-war years

In 1947, the Norwegian people, by public subscription, purchased the royal yacht Norge for the King.[25]

In 1952, he attended the funeral of his wife's nephew King George VI and openly wept.

The King's granddaughter, Princess Ragnhild, married businessman Erling Lorentzen (of the Lorentzen family) on 15 May 1953, being the first member of the new Norwegian royal family to marry a commoner.[26]

Haakon lived to see two of his great-grandchildren born; Haakon Lorentzen (b. 23 August 1954) and Ingeborg Lorentzen (b. 3 February 1957).

Crown Princess Märtha died of cancer on 5 April 1954.[27]

King Haakon VII fell in his bathroom at the estate at the Bygdøy Royal Estate (Bygdøy kongsgård) in July 1955. This fall, which occurred just a month before his eighty-third birthday, resulted in a fracture to the thighbone and, although there were few other complications resulting from the fall, the King was left using a wheelchair. The once-active King was said to have been depressed by his resulting helplessness and began to lose his customary involvement and interest in current events. With Haakon's loss of mobility, and as his health deteriorated further in the summer of 1957, Crown Prince Olav appeared on behalf of his father on ceremonial occasions and took a more active role in state affairs. [28]

Death and legacy

Haakon died at the Royal Palace in Oslo on 21 September 1957. He was 85 years old. At his death, Olav succeeded him as Olav V. Haakon was buried on 1 October 1957 alongside his wife in the white sarcophagus in the Royal Mausoleum at Akershus Fortress. He was the last surviving son of King Frederick VIII of Denmark.

Haakon VII is regarded by many as one of the greatest Norwegian leaders of the pre-war period, managing to hold his young and fragile country together in unstable political conditions. He was ranked highly in the Norwegian of the Century poll in 2005.[29]

Titles, styles, and honours

Titles and styles

- 7 September 1872 – 18 November 1905: His Royal Highness Prince Carl of Denmark

- 18 November 1905 – 21 September 1957: His Majesty The King of Norway

Honours

The King Haakon VII Sea in East Antarctica is named in the king's honour as well as the entire plateau surrounding the South Pole was named King Haakon VII Vidde by Roald Amundsen when he in 1911 became the first human to reach the South Pole. See Polheim.[30]

In 1914 Haakon County in the American state of South Dakota was named in his honour.[31]

Two Royal Norwegian Navy ships—King Haakon VII, an escort ship in commission from 1942 to 1951, and Haakon VII, a training ship in commission from 1958 to 1974—have been named after King Haakon VII.[32]

For his struggles against the Nazi regime and his effort to revive the Holmenkollen ski festival following World War II, King Haakon VII earned the Holmenkollen medal in 1955 (Shared with Hallgeir Brenden, Veikko Hakulinen, and Sverre Stenersen), one of only 11 people not famous for Nordic skiing to receive this honour. (The others are Norway's Stein Eriksen, Borghild Niskin, Inger Bjørnbakken, Astrid Sandvik, King Olav V (his son), Erik Håker, Jacob Vaage, King Harald V (his paternal grandson), and Queen Sonja (his paternal granddaughter-in-law), and Sweden's Ingemar Stenmark).[33]

His father-in-law King Edward VII appointed him Honorary Lieutenant in the British Fleet shortly after succeeding in February 1901.[34] His father King Frederick VIII appointed him Admiral of the Royal Danish Navy on 20 November 1905.[35]

- National[36]

Denmark:[37]

Denmark:[37]

- Knight of the Elephant, 3 August 1890

- Cross of Honour of the Order of the Dannebrog, 3 August 1890

- Grand Commander of the Dannebrog, 28 July 1912

- King Christian X's Freedom Medal

- Commemorative Medal for King Christian IX and Queen Louise's Golden Wedding anniversary

- Commemorative Medal for King Christian IX's 100th birthday

- Commemorative Medal for King Frederik VIII's 100th birthday

Norway:

Norway:

- War Cross with Sword

- Gold Medal for Outstanding Civic Achievement

- Grand Master of the Order of St. Olav, 18 November 1905

- Foreign[36]

Austria: Grand Star of the Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria

Austria: Grand Star of the Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria.svg.png.webp) Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 2 October 1906[38]

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 2 October 1906[38] Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross, with Collar

Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross, with Collar Czechoslovakia:

Czechoslovakia:

- Grand Cross of the White Lion, 1937[39]

- Czechoslovakian Freedom Cross

.svg.png.webp) Ethiopian Imperial Family: Collar of the Order of Solomon

Ethiopian Imperial Family: Collar of the Order of Solomon Finland: Grand Cross of the White Rose, with Collar, 1926[40]

Finland: Grand Cross of the White Rose, with Collar, 1926[40].svg.png.webp) France:

France:

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

- Cross of War (1939–1945)

- Médaille Militaire

.svg.png.webp) Greek Royal Family:

Greek Royal Family:

- War Cross, 1940

- Grand Cross of the Redeemer, 1947

Iceland: Grand Cross of the Falcon, with Collar, 1955[41]

Iceland: Grand Cross of the Falcon, with Collar, 1955[41]_crowned.svg.png.webp) Italian Royal Family: Knight of the Annunciation, 12 April 1909[42]

Italian Royal Family: Knight of the Annunciation, 12 April 1909[42].svg.png.webp) Japan: Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum

Japan: Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum.svg.png.webp) German Imperial and Royal Family:

German Imperial and Royal Family:

Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion

Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion Peru: Grand Cross of the Sun of Peru, in Diamonds, 1922

Peru: Grand Cross of the Sun of Peru, in Diamonds, 1922 Poland: Knight of the White Eagle, 1930

Poland: Knight of the White Eagle, 1930.svg.png.webp) Portuguese Royal Family:

Portuguese Royal Family:

- Grand Cross of the Sash of the Three Orders

- Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword

Romanian Royal Family: Grand Cross of the Order of Carol I, with Collar

Romanian Royal Family: Grand Cross of the Order of Carol I, with Collar Russian Imperial Family:

Russian Imperial Family:

- Knight of St. Andrew

- Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky

- Knight of the White Eagle

- Knight of St. Anna, 1st Class

- Knight of St. Stanislaus, 1st Class

.svg.png.webp) Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, with Collar, 16 July 1910[43]

Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, with Collar, 16 July 1910[43].svg.png.webp) Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, 30 May 1893[44]

Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, 30 May 1893[44] Thailand: Knight of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri

Thailand: Knight of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri.svg.png.webp) Turkish Imperial Family: Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class in Diamonds

Turkish Imperial Family: Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class in Diamonds United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

- Honorary Grand Cross of the Bath (civil), 21 July 1896[45]

- Honorary Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order, 2 February 1901 – on the day of the funeral of Queen Victoria[46]

- Honorary Colonel of the Norfolk Yeomanry, 11 June 1902[47]

- Royal Victorian Chain, 9 August 1902[48]

- Stranger Knight of the Garter, 25 November 1906[49]

- Bailiff Grand Cross of St. John, 12 June 1926[50]

- Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee Medal

- King Edward VII Coronation Medal

- Honorary Citizen of Largs, Scotland[51]

In popular culture

Haakon was portrayed by Jakob Cedergren in the 2009 NRK drama series Harry & Charles, a series that focused on the events leading up to the election of King Haakon in 1905. Jesper Christensen portrayed the King in the 2016 film The King's Choice (Kongens nei) which was based on the events surrounding the German invasion of Norway and the King's decision to resist. The film won widespread critical acclaim, and was Norway's submission for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film at the 89th Academy Awards. The film made the shortlist of nine finalists in December 2016.[52][53][54][55]

Ancestry

See also

- List of state visits made by King Haakon VII of Norway

- List of people on the cover of Time Magazine: 1920s − 3 May 1926

Notes

- "Carl (Haakon VII)". Amalienborg. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Kong Olav 5". nrk.no. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh, ed. (1977). Burke's Royal Families of the World. 1. London, U.K.: Burke's Peerage Ltd. p. 71.

- Grimnes, Ole Kristian (13 February 2009). "Haakon 7". Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- "The Queen Receives". Time. 18 June 1923. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Berg, Roald (1995). Norge på egen hånd 1905–1920 (Norsk utenrikspolitikks historie, volume 2) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. p. 309. ISBN 8200223949.

- "Jubilee". Time. 8 December 1930. p. 1. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- English Heritage (2005). "Blue Plaque for King Haakon VII of Norway". English Heritage. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- (Official site of the Norwegian Royal House, in Norwegian)

- "Queen Maud of Norway". talknorway.no. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- The account and quotation were recorded by one of the cabinet members and were recounted in William L. Shirer's The Challenge of Scandinavia.

- Haarr, Geirr H. (2009). The German Invasion of Norway. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1848320321.

- Sir Gustaf von Platen in Bakom den gyllene fasaden Bonniers ISBN 9100580481 pp. 445–446

- "Mine plikter – "Kongens andre nei"". kongehuset.no. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "The Tragedy of HMS Glorious". cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "British Government News & Press Releases – 25 October 2005: Blue Plaque for King Haakon VII of Norway". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- Norway: the official site in the UK – News 27 October 2012 – Princess Astrid unveils blue plaque

- The Diocese of Southwark, The Bridge, December 2009 – January 2010: Scandinavia in Rotherhithe

- William Lawrence Shirer: The challenge of Scandinavia: Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland in our time, Robert Hale, 1956

- Dahl; Hjeltnes; Nøkleby; Ringdal; Sørensen, eds. (1995). "Norge i krigen 1939–45. Kronologisk oversikt". Norsk krigsleksikon 1940–45 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Cappelen. p. 11. ISBN 8202141389.

- "Krigsårene 1940–1945". Royal House of Norway (in Norwegian). 31 January 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- H7, Time, Monday, 30 September 1957

- "First Out, First In". Time. 11 June 1945. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- The Norwegian Royal House's official page about the escape, the five years in exile and the return after World War II (in English)

- "Drømmen om Norge". kongehuset.no. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Erling Sven Lorentzen". paperdiscoverycenter.org. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Crown Princess Märtha (1901–1954)". kongehuset.no. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Jon Gunnar Arntzen. "Bygdøy kongsgård". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Han er Norges beste konge gjennom tidene". www.vg.no (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "Amundsen's original South Pole Station". southpolestation.com. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Haakon County South Dakota". genealogytrails.com. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Skoleskip KNM Haakon VII". sjohistorie.no. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Olympians Who Received the Holmenkollmedaljen". sports-reference.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "No. 27285". The London Gazette. 15 February 1901. p. 1147.

- Marineministeriets foranstaltning (1912). "Haandbog for Søværnet for 1912" (PDF) (in Danish). Copenhagen: H.H. Thieles Bogtrykkeri. p. 9. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- Royal House of Norway web page on King Haakon VII's decorations (Norwegian) Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- Bille-Hansen, A. C.; Holck, Harald, eds. (1953) [1st pub.:1801]. Statshaandbog for Kongeriget Danmark for Aaret 1953 [State Manual of the Kingdom of Denmark for the Year 1953] (PDF). Kongelig Dansk Hof- og Statskalender (in Danish). Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz A.-S. Universitetsbogtrykkeri. pp. 16, 18. Retrieved 16 September 2019 – via da:DIS Danmark.

- Royal Decree of 2 October 1906

- "Kolana Řádu Bílého lva aneb hlavy států v řetězech" (in Czech), Czech Medals and Orders Society. Retrieved 2018-08-09.

- "Suomen Valkoisen Ruusun Suurristi Ketjuineen". ritarikunnat.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Icelandese Presidency Website Archived 17 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine , Hakon VII ; konungur ; Noregur ; 25 May 1955 ; Stórkross með keðju (= Haakon VII , King , Norway, 25 May 1955, Grand Cross with Collar)

- Italy. Ministero dell'interno (1920). Calendario generale del regno d'Italia. p. 57.

- "Caballeros de la insigne orden del toisón de oro". Guía Oficial de España (in Spanish). 1929. p. 216. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Sveriges statskalender (in Swedish), 1905, p. 440, retrieved 20 February 2019 – via runeberg.org

- Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) The Knights of England, I, London, p. 214

- "No. 27285". The London Gazette. 15 February 1901. p. 1145.

- "No. 27441". The London Gazette. 10 June 1902. p. 3756.

- Shaw, p. 415

- "Garter Knights Meet in Splendid Ceremony ... King Haakon is Invested," New York Times. 25 November 1906.

- "No. 33284". The London Gazette. 14 June 1927. p. 3836.

- "Miscellany". Time. 25 December 1944. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Johansen, Øystein David (8 September 2016). ""Kongens nei" er Norges Oscar-kandidat". Verdens Gang. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- Sandwell, Ian (8 September 2016). "Oscars: Norway picks 'The King's Choice'". ScreenDaily. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- "Oscars: Nine Films Advance in Foreign-Language Race". Variety. 15 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ""Kongens nei" er Norges Oscar-kandidat". VG. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

References

- Greve, Tim (1983). Haakon VII of Norway: Founder of a New Monarchy. Hurst. ISBN 978-0905838663.

- Dahl, Hans Fredrik (1995). Norsk krigsleksikon 1940–45. Oslo: Cappelen. ISBN 8202141389.

- Bomann-Larsen, Tor (2004). Haakon og Maud II/Folket. Oslo: Cappelen. ISBN 978-8202225292.

- Bomann-Larsen, Tor (2006). Haakon og Maud III/Vintertronen. Oslo: Cappelen. ISBN 978-8202246655.

- Shirer, William L. (1956). The Challenge of Scandinavia. London: Robert Hale. OCLC 930493567.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haakon VII of Norway. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Haakon VII of Norway. |

- Official Website of the Royal House of Norway

- King Haakon − biography (Official Website of the Royal House of Norway)

- Prince Carl (Haakon VII) at the website of the Royal Danish Collection at Amalienborg Palace

- The Royal Norwegian Order of St Olav − H.M. King Haakon VII the former Grand Master of the Order

Haakon VII House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg Cadet branch of the House of Oldenburg Born: 3 August 1872 Died: 21 September 1957 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Title last held by Oscar II |

King of Norway 1905–1957 |

Succeeded by Olav V |