Halisaurus

Halisaurus is an extinct genus of marine reptile belonging to the mosasaur family. The holotype, consisting of an angular and a basicranium fragment discovered near Hornerstown, New Jersey, already revealed a relatively unique combination of features and prompted a new genus to be described. It was named by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1869 and means "ocean lizard". It was renamed by Marsh to Baptosaurus in 1870, since he believed the name to already be preoccupied by the fish Halosaurus. According to modern rules, a difference of a letter is enough and the substitute name is unneeded, making "Baptosaurus" a junior synonym.

| Halisaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton in Thermopolis, Wyoming. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Superfamily: | †Mosasauroidea |

| Family: | †Mosasauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Halisaurinae |

| Genus: | †Halisaurus Marsh, 1869 |

| Type species | |

| †Halisaurus platyspondylus | |

| Species | |

| |

Since its description, more complete remains have been uncovered from fossil deposits throughout the world with particularly complete remains found in Morocco and the United States. The genus remains a key taxon in mosasaur systematics due to its unique set of features and as the most complete representative of its subfamily, the Halisaurinae.

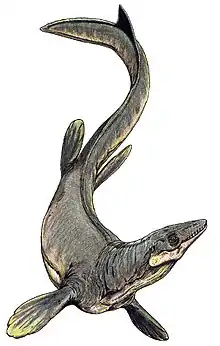

With a length of 3–4 m (9.8–13.1 ft), Halisaurus was comparatively small by mosasaur standards. Though bigger than earlier and more basal mosasaurs, such as Dallasaurus, the sleek Halisaurus would have been dwarfed by many of its contemporaries, such as Tylosaurus and larger species of Clidastes.

Description

Halisaurus appeared relatively early in the evolutionary history of the mosasaurs, during the Santonian. As such, the genus retains many primitive characteristics, as does the Halisaurinae at large. Both H. platyspondylus and H. arambourgi reached lengths of between 3 and 4 metres (9.8 - 13.1 feet). The length of the dubious H. onchognathus is difficult to tell due to the lack of remains, but was likely similar.

As in other halisaurines, the flippers of Halisaurus are poorly differentiated which means that the genus lacked the hydrophalangy of more advanced mosasaurs. That Halisaurus was a relatively poor swimmer is relatively surprising considering its small size, since other small and medium-sized mosasaurs were mostly adept swimmers. The description of Phosphorosaurus ponpetelegans revealed that Phosphorosaurus, another member of the Halisaurinae, was highly specialized to compensate for its lack of hydrophalangy.[1]

Classification and species

The exact position of Halisaurus within the larger mosasaur family tree has long been considered controversial. The type specimen of H. platyspondylus is not comprehensive and only preserves an angular and a basicranium fragment. Though the specimen does not reveal much about the mosasaur, it was noted by D.A. Russell in his Systematics and Morphology of American Mosasaurs (1967) that the angular resembles that of Platecarpus but is more symmetrically heart-shaped in anterior aspect and appears slightly inflated in later profile with a convex anteroventral outline that is continuous with the anteroexternal margin of the articular surface, as in the genus Clidastes. The similarities with both Platecarpus and Clidastes were problematic, as said genera have always been classified in separate subfamilies, the Plioplatecarpinae and Mosasaurinae respectively. Russell referred the genus to the Plioplatecarpinae on the basis of a Platecarpus-like suprastapedial process in specimens referred to H. onchognathus.[2]

Several discoveries throughout the 1980s and 1990s helped shed light on Halisaurus, with more complete specimens of the type species H. platyspondylus being discovered and Phosphorosaurus ortliebi being momentarily reassigned to the genus by Lingham-Soliar (1996).[3] In 2005, the species Halisaurus sternbergii was reassigned to its own genus, Eonatator, along with the description of the new species Halisaurus arambourgi by Nathalie Bardet and colleagues. With the description of Eonatator as a closely related genus to Halisaurus, the two genera were grouped into the new subfamily Halisaurinae, which was then believed to be a sister-group to more advanced mosasaurs.[4]

The most recent major phylogenetic analysis of mosasaurs, conducted by Tiago R. Simões and colleagues in May 2017, recovered Halisaurus and the rest of the Halisaurinae as a sister group to the Mosasaurinae. This would mean that the halisaurines are more closely related to the mosasaurines than the russellosaurines (genera such as Tylosaurus and Plesiopatecarpus) are.[5]

Below is a cladogram following an analysis by Takuya Konishi and colleagues (2015) done during the description of Phosphorosaurus ponpetelegans, which showcases the internal relationships within the Halisaurinae, showing Halisaurus as the basalmost genus of the subfamily.[1] The analysis excluded the dubious H. onchognathus and the genus Pluridens.

| Halisaurinae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Two species of Halisaurus are considered valid; H. platyspondylus and H. arambourgi. The species H. onchognathus, known from Campanian or Santonian deposits that were once part of the Western Interior Seaway, is considered dubious due to all the known remains of the species having been destroyed in the Second World War. Apart from the named species, fragmentary remains have been referred to the genus from across the world. Though the designation of these remains as Halisaurus is debatable in most cases, unnamed species are known from the Campanian of Texas, the Maastrichtian of California and the Santonian of Peru (which significantly expands the known temporal range of the genus).[6]

Halisaurus platyspondylus

Halisaurus platyspondylus is the type species of Halisaurus, having been named by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1869. The species name means "flat-spined". Referred specimens include the type specimen YPM 444 (consisting of an angular and a basicranium fragment) from the New Egypt Formation (New Jersey), which is Maastrichtian in age. Important subsequent specimens include NJSM 12146 (an incomplete cranium from the Navesink Formation, New Jersey), USNM 442450 (an incomplete skeleton from the Severn Formation of Maryland).[4] The species is also known from the Mount Laurel and Merchantville Formations of Delaware, implying that the species ranged across the eastern coast of North America during the Middle to Late Maastrichtian.[7]

This species is differentiated from other species by the narrow and oblique shape of its quadrate, the broadly rounded and posteriorly rounded external nares and the lack of anterior ridges on its frontal as well as its pterygoid preserving nine teeth.[4]

Halisaurus arambourgi

Halisaurus arambourgi means "Arambourg's ocean lizard" and is named in honor of Professor Camille Arambourg due to his work on fossil vertebrates in North Africa and the Middle East.

Like H. platyspondylus, H. arambourgi is Late Maastrichtian in age, though specimens of this species have been found across northern Africa and potentially in the Middle East. The type specimen, MNHN PMC 14, is an incomplete skeleton that includes a disarticulated skull and 27 associated articulated vertebrae from the Grand Daoui area near Khouribga in central Morocco.

The fossils of H. arambourgi preserve several features that distinguish it from H. platyspondylus, among them the shape of its external nares (V-shaped anteriorly and U-shaped posteriorly), the shape of its quadrate (which has an oval vertical stapedial notch) and the presence of anterior ridges on the frontal. Its pterygoid bone also preserves twelve teeth (three more than in H. platyspondylus).[4]

References

- Takuya Konishi, Michael W. Caldwell, Tomohiro Nishimura, Kazuhiko Sakurai & Kyo Tanoue (2015) A new halisaurine mosasaur (Squamata: Halisaurinae) from Japan: the first record in the western Pacific realm and the first documented insights into binocular vision in mosasaurs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology (advance online publication) DOI:10.1080/14772019.2015.1113447 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14772019.2015.1113447#abstract

- Russell, D. A. (1967). "Systematics and morphology of American mosasaurs (Reptilia, Sauria)" (PDF). Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 23.

- Lingham-Soliar, T. 1996. The first description of Halisaurus (Reptilia Mosasauridae) from Europe, from the Upper Cretaceous of Belgium. Bulletin de l'Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre, 66, 129–136.

- Bardet, N., Pereda Suberbiola, X., Iarochene, M., Bouya, B. & Amaghzaz, M. 2005. A new species of Halisaurus from the Late Cretaceous phosphates of Morocco, and the phylogenetical relationships of the Halisaurinae (Squamata: Mosasauridae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 143, 447–472.

- Simões, Tiago R.; Vernygora, Oksana; Paparella, Ilaria; Jimenez-Huidobro, Paulina; Caldwell, Michael W. (2017-05-03). "Mosasauroid phylogeny under multiple phylogenetic methods provides new insights on the evolution of aquatic adaptations in the group". PLOS ONE. 12 (5): e0176773. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0176773. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5415187. PMID 28467456.

- Caldwell, Michael W.; Jr, Gorden L. Bell (1995-09-14). "Halisaurus sp. (Mosasauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous (?Santonian) of east-central Peru, and the taxonomic utility of mosasaur cervical vertebrae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 15 (3): 532–544. doi:10.1080/02724634.1995.10011246. ISSN 0272-4634.

- "Fossilworks: Mosasaurus". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- Sea Dragons: Predators Of The Prehistoric Oceans by Richard Ellis page (p. 214)

- Ancient Marine Reptiles by Jack M. Callaway and Elizabeth L. Nicholls page (p. 283)