Historicity and origin of the resurrection of Jesus

The historicity and origin of the resurrection of Jesus has been the subject of historical research and debate, as well as a topic of discussion among theologians. The accounts of the Gospels, including the empty tomb and the appearances of the risen Jesus to his followers, have been interpreted and analyzed in diverse ways, and have been seen variously as historical accounts of a literal event, as accurate accounts of visionary experiences, as non-literal eschatological parables, and as fabrications of early Christian writers, among various other interpretations. It has been suggested, for example, that Jesus did not die on the cross, that the empty tomb was the result of Jesus' body having been stolen, or, as was common with Roman crucifixions, that Jesus was never entombed.

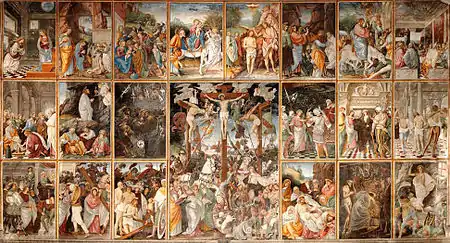

| Part of a series on |

| Death and Resurrection of Jesus |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

Post-Enlightenment historians work with methodological naturalism,[1][2] and therefore reject miracles as objective historical facts.[1]

Origin: Cultural and theological background

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

Resurrection and the afterlife of the soul

Of the three main Jewish sects of the 1st century AD, the Sadducees held that both soul and body perished at death, the Essenes that the soul was immortal but the flesh was not, and the Pharisees that the soul was immortal and that the body would be resurrected to house it.[3] Of these three positions, Jesus and the early Christians appear to have been closest to that of the Pharisees.[4] Resurrection was available to the righteous alone, and would make them equal to the angels, as the Gospels have Jesus tell: "Those who are accounted worthy ... to the resurrection from the dead ... are equal to the angels and are children of God..." (Mark 12:24-25, Luke 20:34-36).[5] Nor would the resurrected body be one of flesh and blood, but an immortal fleshless body of the same celestial nature as the sun, moon and stars.[6]

Jews did not believe that the dead could enter Heaven – mankind's place was the earth, and heaven was for God and the heavenly beings.[7] The Greeks held a similar view, but they also held that a man of exceptional merit could be exalted as a god after his death.[8] The successors of Alexander the Great made this idea very well known throughout the Middle East, in particular through coins bearing his image – a privilege previously reserved for gods – and although originally foreign to the Romans, the doctrine was soon borrowed by the emperors for purposes of political propaganda.[8] According to the theology of Imperial Roman apotheosis, the earthly body of the recently deceased emperor vanished, he received a new and divine one in its place, and was then seen by credible witnesses.[9] Thus, in a story similar to the Gospel appearances of the resurrected Jesus and the commissioning of the disciples, Romulus, the founder of Rome, descended from the sky to command a witness to bear a message to the Romans regarding the city's greatness ("Declare to the Romans the will of Heaven that my Rome shall be the capital of the world...") before being taken up on a cloud.[10]

The experiences of the risen Christ attested by the earliest written sources – the "primitive Church" creed of 1 Corinthians 15:3-5, in 1 Corinthians 15:8 and Galatians 1:16 – are ecstatic rapture events and "invasions of heaven".[11] A physical resurrection was unnecessary for this visionary mode of seeing the risen Christ, but the general movement of subsequent New Testament literature is towards the physical nature of the resurrection.[12] This development is linked to the changing make-up of the Christian community: Paul the Apostle and the earliest Christ followers were Jewish, and Second Temple Judaism emphasised the life of the soul; the gospel writers, in an overwhelmingly Greco-Roman church, stressed instead the pagan belief in the hero who is immortalised and deified in his physical body.[13] In this Hellenistic resurrection paradigm Jesus dies, is buried, and his body disappears (with witnesses to the empty tomb); he then returns in an immortalised physical body, able to appear and disappear at will like a god, and returns to the heavens which are now his proper home.[14]

Theological considerations

The earliest Jewish followers of Jesus (the Jewish Christians) understood him as the son of man in the Jewish sense, a human who, through his perfect obedience to God's will, was resurrected and exalted to heaven in readiness to return as the son of man (the figure from Daniel 79), ushering in and ruling over the Kingdom of God.[15] Paul has already moved away from this apocalyptic tradition towards a position where Christology and soteriology take precedence: Jesus is no longer the one who proclaims the message of the imminently coming Kingdom, he actually is the kingdom, the one in whom the kingdom of God is already present.[16] This is also the message of Mark, a gentile writing for a church of gentile Christians, for whom Jesus as "Son of God" has become a divine being whose suffering, death and resurrection are essential to God's plan for redemption.[17]

Matthew presents Jesus' appearance in Galilee (Matthew 28:19-20) as a Greco-Roman apotheosis, the human body transformed to make it fitting for paradise.[18] He goes beyond the ordinary Greco-Roman forms, however, by having Jesus claim "all authority ... in heaven and on earth" (28:18) – a claim no Roman hero would dare make – while charging the apostles to bring the whole world into a divine community of righteousness and compassion.[19] Notable too is that the expectation of the imminent Second Coming has been delayed: it will still come about, but first the whole world must be gathered in.[19]

In Paul and the first three gospels, and also in Revelation, Jesus is portrayed as having the highest status, but the Jewish commitment to monotheism prevents the authors from depicting him as fully one with God.[20] This stage was reached first in the Christian community which produced the Johannine literature: only here in the New Testament does Jesus become God incarnate, the body of the resurrected Jesus bringing Doubting Thomas to exclaim, "My Lord and my God!"[21][22]

Historicity

Textual sources

The earliest mention of the resurrection is in the Pauline epistles, which tradition dates from between 50 and 58 AD.[23][24] Paul shows very little interest in the teachings of Jesus, focusing attention instead on his role as the suffering, dying, resurrected Christ who would return at any moment to gather the elect and judge the world.[25] In his first epistle to the Corinthians Paul passes on a creed that he says he received shortly after his conversion (1Co. 15:1-8).[26] Christ, he says, was raised on the third day "according to the scriptures: and then appeared to various followers.[lower-alpha 1] He lists, in what appears to be in chronological order, a first appearance to Peter, then to "the Twelve," then to five hundred at one time, then to James (presumably James the brother of Jesus), then to "all the Apostles," and last to Paul himself.[26] Paul does not mention any appearances to women at the tomb, and other New Testament sources do not mention any appearance to a crowd of 500. According to Habermas, this is an indication of the lack of credibility of women, where their testimony has already been removed from the early creed. [26] There is general agreement that the list is pre-Pauline, dated to within 6 months and no later than 3 years after Jesus's death, but less on how much of it belongs to the tradition and how much is from Paul: most scholars feel that Peter and the Twelve are original, but not all believe the same of the appearances to the 500, James, and "all the Apostles".[27]

The next texts that mention the resurrection are the four Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. These date from between 70 and 110 AD, and it is almost certain that none of them were written directly by eyewitnesses, although Luke mentions being in direct contact with them.[28] [29] To take a few examples, according to the Synoptic Gospels Jesus's ministry appears to take one year, inferred from the mentions of a sole instance of Jesus's visit to the Jerusalem temple. His ministry was spent primarily in Galilee, and climaxed with a single visit to Jerusalem at which he cleansed the Temple of the money-changers, while in John, Jerusalem was the focus of Jesus' mission, he visited it three times (possibly indicating his mission lasted three years rather than one), and the cleansing of the Temple took place at the beginning rather than the end of the ministry.[30] Mark, written in the period 65-75 CE, originally contained little mention of post-resurrection appearances, although Mark 16:7, in which the young man discovered in the tomb instructs the women to tell "the disciples and Peter" that Jesus will see them again in Galilee, hints that the author may have known of the tradition.[31] According to Telford, the verb of seeing Jesus, horan, is used in 1 Corinthians as well as Mark, indicating the author of Mark's knowledge of the oral sayings.[32]

The authors of Matthew (c.80-90 CE) and Luke/Acts (a two-part work by the same anonymous author, usually dated to around 80–90 CE) based their lives of Jesus on the Gospel of Mark[33][34] but diverge after Mark 16:8. Whereas Mark ends with the discovery of the empty tomb, Matthew continues on with two post-resurrection appearances, the first to Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary" at the tomb, and the second, based on Mark 16:7, to all the disciples on a mountain in Galilee, where Jesus claims authority over heaven and earth and commissions the disciples to preach the gospel to the whole world.[35] Luke does not mention any of the appearances reported by Matthew, [36] and incorporates Jerusalem rather than just Galilee as the sole location.[32] In Luke, Jesus appears to Cleopas and an unnamed disciple on the road to Emmaus, to Peter (reported by the other apostles), and to the eleven remaining disciples at a meeting with others. The appearances reach their climax with the ascension of Jesus before the assembled disciples on a mountain outside Jerusalem. In addition, Acts has appearances to Paul on the road to Damascus, to the martyr Stephen, and to Peter, who hears the voice of Jesus.

The Gospel of John was written some time after 80 or 90 CE, and differs significantly from both Matthew and Luke.[37] Here Jesus appears at the empty tomb to Mary Magdalene (who initially fails to recognise him), then to the disciples minus Thomas, then to all the disciples including Thomas (the "doubting Thomas" episode), finishing with an extended appearance in Galilee to Peter and six (not all) of the disciples.[38] Chapter 21, the appearance in Galilee, is widely believed to be a later addition to the original gospel.[39] Later sources, such as the Gnostic gospels, which were rejected as heresy, with large embellishments can be contrasted with the canonical Gospels and help to separate later embellishment and invention. [32]

The empty tomb

There are various arguments against the historicity of the resurrection story. For example, the number of other historical figures and gods with similar death and resurrection accounts has been pointed out.[40][lower-alpha 2] However the majority consensus among biblical scholars is that the genre of the Gospels is a kind of ancient biography.[42] Christ-myth theorist Robert M. Price claims that if the resurrection could, in fact, be proven through science or historical evidence, the event would lose its miraculous qualities.[40]

New Testament historian Bart D. Ehrman recognizes that "Some scholars have argued that it's more plausible that in fact Jesus was placed in a common burial plot, which sometimes happened, or was, as many other crucified people, simply left to be eaten by scavenging animals." He further elaborates by saying: "[T]he accounts are fairly unanimous in saying (the earliest accounts we have are unanimous in saying) that Jesus was in fact buried by this fellow, Joseph of Arimathea, and so it's relatively reliable that that's what happened."[43] He later changed his mind, stating that part of the crucifixion punishment was being "left to decompose and serve as food for scavenging animals", i.e. left without decent burial, since everyone wanted to have a decent burial in the Antiquity.[44]

Géza Vermes presents six valid possibilities to explain the empty tomb narrative: (1) The body was removed by someone unconnected with Jesus; (2) The body was stolen by the disciples; (3) The empty tomb (the tomb visited by the women) was not the tomb of Jesus; (4) Buried alive, Jesus later left the tomb; (5) Jesus recovered from a coma and departed Judea; (6) There was a spiritual, not bodily, resurrection. Vermes states that none of these six possibilities is likely to be historical.[45] According to N. T. Wright in his book The Resurrection of the Son of God, "There can be no question: Paul is a firm believer in bodily resurrection. He stands with his fellow Jews against the massed ranks of pagans; with his fellow Pharisees against other Jews."[46]

According to Gary Habermas, "Many other scholars have spoken in support of a bodily notion of Jesus’ resurrection."[47] Habermas also points out three facts in support of Paul's belief in a physical resurrection body. (1) Paul is a Pharisee and therefore (unlike the Sadducees) believes in a physical resurrection. (2) In Philippians 3:11 Paul says "That I may attain to the ek anastasis (out-resurrection)" from the dead, which according to Habermas means that "What goes down is what comes up". And (3) In Philippians 3:20-21 "We look from heaven for Jesus who will change our vile soma (body) to be like unto his soma (body)". According to Habermas, if Paul meant that we would change into a spiritual body then Paul would have used the Greek pneuma instead of soma.[48]

According to a rough estimate by scholar Gary Habermas, 75% of New Testament scholars are in favor of an empty tomb, while 25% reject an empty tomb.[49]

Post-resurrection appearances

New Testament scholar and theologian E. P. Sanders argues that a concerted plot to foster belief in the resurrection would probably have resulted in a more consistent story, and that some of those who were involved in the events gave their lives for their belief. Sanders offers his own hypothesis, saying "there seems to have been a competition: 'I saw him,' 'so did I,' 'the women saw him first,' 'no, I did; they didn't see him at all,' and so on."[50] "That Jesus' followers (and later Paul) had resurrection experiences is, in my judgment, a fact. What the reality was that gave rise to the experiences I do not know."[51]

James Dunn notes that whereas the apostle Paul's resurrection experience was "visionary in character" and "non-physical, non-material," the accounts in the Gospels are very different. He contends that the "massive realism'...of the [Gospel] appearances themselves can only be described as visionary with great difficulty - and Luke would certainly reject the description as inappropriate," and that the earliest conception of resurrection in the Jerusalem Christian community was physical.[52] Similarly, Helmut Koester writes that the stories of the resurrection were originally epiphanies in which the disciples are called to a ministry by the risen Jesus and were interpreted as physical proof of the event at a secondary stage. He contends that the more detailed accounts of the resurrection are also secondary and do not come from historically trustworthy sources, but instead belong to the genre of the narrative types.[53]

N. T. Wright argues that the account of the empty tomb and the visionary experiences point towards the historical reality of the resurrection.[54] He suggests that multiple lines of evidence from the New Testament and the early Christian beliefs it reflects shows that it would be highly unlikely that belief in the empty tomb would simply appear without a clear basis in the memory of early Christians. In tandem with the historically-certain visionary experiences of the early disciples and apostles, Jesus' resurrection as a historical reality becomes far more plausible. Contrary to various theologians and historians in recent decades, Wright treats the resurrection as a historical and accessible event, rather than as a 'supernatural' or 'metaphysical' event. Among Wright's critics, author and professor Lawrence Shapiro states that "evidence for the resurrection is nowhere near as complete or convincing as the evidence on which historians rely to justify belief in other historical events such as the destruction of Pompeii."[55]

See also

Notes

- Paul informs his readers that he is passing on what he has been told, "that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, and then to the Twelve. After that, he appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers and sisters at the same time, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles, and last of all he appeared to me also, as to one abnormally born."

- Robert M. Price points to the accounts of Adonis, Apollonius of Tyana, Asclepius, Attis, Empedocles, Hercules, Osiris, Oedipus, Romulus, Tammuz, and others.[41]

References

Citations

- McGrew, Timothy, "Miracles", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/miracles/

Flew, Antony, 1966, God and Philosophy, London: Hutchinson.

Ehrman, Bart D., 2003, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings, 3rd ed., New York: Oxford University Press.

Bradley, Francis Herbert, 1874, “The Presuppositions of Critical History,” in Collected Essays, vol. 1, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1935.

McGrew's conclusion: historians work with methodological naturalism, which precludes them from establishing miracles as objective historical facts (Flew 1966: 146; cf. Bradley 1874/1935; Ehrman 2003: 229). - Bart D. Ehrman (23 September 1999). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-19-983943-8.

As I've pointed out, the historian cannot say that demons—real live supernatural spirits that invade human bodies—were actually cast out of people, because to do so would be to transcend the boundaries imposed on the historian by the historical method, in that it would require a religious belief system involving a supernatural realm outside of the historian's province.

- Schäfer 2003, p. 72.

- Van Voorst 2000, p. 430.

- Tabor 2013, p. 58.

- Endsjø 2009, p. 145.

- Tabor 2013, p. 54.

- Cotter 2001, p. 131.

- Cotter 2001, p. 133-135.

- Collins, p. 46.

- De Conick 2006, p. 6.

- Finney 2016, p. 181.

- Finney 2016, p. 183.

- Finney 2016, p. 182.

- Telford 1999, p. 154-155.

- Telford 1999, p. 156.

- Telford 1999, p. 155.

- Cotter 2001, p. 149.

- Cotter 2001, p. 150.

- Chester 2016, p. 15.

- Chester 2016, p. 15-16.

- Vermes 2001, p. unpaginated.

- Roetzel 2000, p. 1019.

- Martin 1995, p. unpaginated.

- Roetzel 2000, p. 1019-1020.

- Taylor 2014, p. 374.

- Plevnik 2009, p. 4-6.

- Reddish 2011, p. 13.

- "Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony". Reformed Faith & Practice. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- Reddish 2011, p. 188.

- Telford 1999, p. 12,149.

- Telford 1999, p. 149.

- Charlesworth 2008, p. unpaginated.

- Burkett 2002, p. 195.

- Cotter 2001, p. 127.

- McEwen, p. 134.

- Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 887-888.

- Quast 1991, p. 130.

- Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 888.

- Robert M. Price, "The Empty Tomb: Introduction; The Second Life of Jesus." In Price, Robert M.; Lowder, Jeffrey Jay, eds. (2005). The Empty Tomb: Jesus Beyond the Grave. Amherst: Prometheus Books. p. 14. ISBN 1-59102-286-X.

- Robert M. Price, "The Empty Tomb: Introduction; The Second Life of Jesus". In Price, Robert M.; Lowder, Jeffrey Jay, eds. (2005). The Empty Tomb: Jesus Beyond the Grave. Amherst: Prometheus Books. pp. 14–15. ISBN 1-59102-286-X.

- Burridge, R. A. (2006). Gospels. In J. W. Rogerson & Judith M. Lieu (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 437

- Bart Ehrman, From Jesus to Constantine: A History of Early Christianity, Lecture 4: "Oral and Written Traditions about Jesus" [The Teaching Company, 2003].

- Bart D. Ehrman (25 March 2014). How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee. HarperCollins. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-06-225219-7.

- Vermes, Geza (2008). The Resurrection: History and Myth. New York: Doubleday. pp. 142–148. ISBN 978-0-7394-9969-6. The quoted material appeared in small caps in Vermes's book.

- Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God, 272; cf. 321

- Resurrection Research from 1975 to the Present: What are Critical Scholars Saying? Link

- From a debate with Anthony Flew on the resurrection of the Jesus. Transcript Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Resurrection Research from 1975 to the Present: "Of these scholars, approximately 75% favor one or more of these arguments for the empty tomb, while approximately 25% think that one or more arguments oppose it. Thus, while far from being unanimously held by critical scholars, it may surprise some that those who embrace the empty tomb as a historical fact still comprise a fairly strong majority."

- "Jesus Christ." Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 10 Jan. 2007

- Sanders, E. P. The Historical Figure of Jesus. New York: Penguin Books, 1993.

- James D.G. Dunn, Jesus and the Spirit: A Study of the Religious and Charismatic Experience of Jesus and the First Christians as Reflected in the New Testament. Eerdmans, 1997. p. 115, 117.

- Helmut Koester, Introduction to the New Testament, Vol. 2: History and Literature of Early Christianity. Walter de Gruyter, 2000. p. 64-65.

- Wright, N.T. (2003). The Resurrection of the Son of God. Fortress Press. ISBN 9780800626792.

- Shapiro, Lawrence (2016). The Miracle Myth. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231542142.

Bibliography

- Barton, John; Muddiman, John (2010). The Pauline Epistles. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191034664.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521007207.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Charlesworth, James H. (2008). The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426724756.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chester, Andrew (2007). Messiah and Exaltation: Jewish Messianic and Visionary Traditions and New Testament Christology. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161490910.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Adela Yarbro (2009). "Ancient Notions of Transferal and Apotheosis". In Seim, Turid Karlsen; Økland, Jorunn (eds.). Metamorphoses: Resurrection, Body and Transformative Practices in Early Christianity. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110202991.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cotter, Wendy (2001). "Greco-Roman Apotheosis Traditions and the Resurrection in Matthew". In Thompson, William G. (ed.). The Gospel of Matthew in Current Study. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846730.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- De Conick, April D. (2006). Paradise Now: Essays on Early Jewish and Christian Mysticism. SBL. ISBN 9781589832572.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dunn, James D. G. (1997). Jesus and the Spirit: A Study of the Religious and Charismatic Experience of Jesus and the First Christians as Reflected in the New Testament. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802842916.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Endsjø, D. (2009). Greek Resurrection Beliefs and the Success of Christianity. Springer. ISBN 9780230622562.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Finney, Mark (2016). Resurrection, Hell and the Afterlife: Body and Soul in Antiquity, Judaism and Early Christianity. Routledge. ISBN 9781317236375.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Geisler, Norman (2004). The Battle for the Resurrection. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781317236375.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lehtipuu, Outi (2015). Debates Over the Resurrection of the Dead: Constructing Early Christian Identity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198724810.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martin, D. Michael (1995). 1, 2 Thessalonians: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 9781433675683.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGrath, Alister E. (2011). Christian Theology: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444397703.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Day, Gail R. (1998). "John". In Newsom, Carol Ann; Ringe, Sharon H. (eds.). Women's Bible Commentary. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780281072606.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parker, D.C. (1997). The Living Text of the Gospels. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521599511.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pate, C. Marvin (2013). Apostle of the Last Days: The Life, Letters and Theology of Paul. Kregel Academic. ISBN 9780825438929.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perkins, Pheme (2014). "Resurrection of Jesus". In Evans, Craig A. (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. ISBN 9781317722243.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Plevnik, Joseph (2009). What are They Saying about Paul and the End Time?. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809145782.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Quast, Kevin (1991). Reading the Gospel of John: An Introduction. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809132973.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reddish, Mitchell (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426750083.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roetzel, Calvin J. (2000). "Paul". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sanders, E.P. (1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141928227.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheehan, Thomas (1990). The First Coming. Polebridge Press. ISBN 9780944344590.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schäfer, Peter (2003). The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World. Routledge. ISBN 9781134403165.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swinburne, Richard (2003). The Resurrection of God Incarnate. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780199257454.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tabor, James (2013). Paul and Jesus: How the Apostle Transformed Christianity. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439123324.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, Mark (2014). 1 Corinthians: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture. B&H Publishing. ISBN 9780805401288.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Telford, W.R. (1999). The Theology of the Gospel of Mark. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521439770.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Voorst, Robert E. (2000). "Eternal Life". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vermes, Geza (2001). The Changing Faces of Jesus. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141912585.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wright, Nicholas Thomas (2003). The Resurrection of the Son of God. Augsburg Fortress. ISBN 9780800626792.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)