Pauline epistles

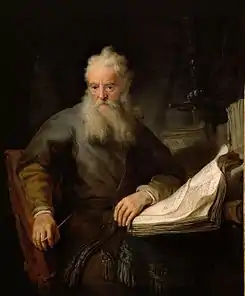

The Pauline epistles, also called Epistles of Paul or Letters of Paul, are the thirteen books of the New Testament attributed to Paul the Apostle, although the authorship of some is in dispute. Among these epistles are some of the earliest extant Christian documents. They provide an insight into the beliefs and controversies of early Christianity. As part of the canon of the New Testament, they are foundational texts for both Christian theology and ethics. The Epistle to the Hebrews, although it does not bear his name, was traditionally considered Pauline (although Origen, Tertullian and Hippolytus amongst others, questioned its authorship), but from the 16th century onwards opinion steadily moved against Pauline authorship and few scholars now ascribe it to Paul, mostly because it does not read like any of his other epistles in style and content.[1] Most scholars agree that Paul actually wrote seven of the Pauline epistles, but that four of the epistles in Paul's name are pseudepigraphic (Ephesians, First Timothy, Second Timothy, and Titus[2]) and that two other epistles are of questionable authorship (Second Thessalonians and Colossians).[2] According to some scholars, Paul wrote these letters with the help of a secretary, or amanuensis,[3] who would have influenced their style, if not their theological content.

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Paul in the Bible |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

See also |

| Events in the Life of Paul according to Acts of the Apostles |

|---|

|

|

The Pauline epistles are usually placed between the Acts of the Apostles and the Catholic epistles in modern editions. Most Greek manuscripts, however, place the General epistles first,[4] and a few minuscules (175, 325, 336, and 1424) place the Pauline epistles at the end of the New Testament.

Order

In the order they appear in the New Testament, the Pauline epistles are:

| Name | Addressees | Greek | Latin | Abbreviations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full | Min. | |||||

| Romans | Church at Rome | Πρὸς Ῥωμαίους | Epistola ad Romanos | Rom | Ro | |

| First Corinthians | Church at Corinth | Πρὸς Κορινθίους Αʹ | Epistola I ad Corinthios | 1 Cor | 1C | |

| Second Corinthians | Church at Corinth | Πρὸς Κορινθίους Βʹ | Epistola II ad Corinthios | 2 Cor | 2C | |

| Galatians | Church at Galatia | Πρὸς Γαλάτας | Epistola ad Galatas | Gal | G | |

| Ephesians | Church at Ephesus | Πρὸς Ἐφεσίους | Epistola ad Ephesios | Eph | E | |

| Philippians | Church at Philippi | Πρὸς Φιλιππησίους | Epistola ad Philippenses | Phil | Phi | |

| Colossians | Church at Colossae | Πρὸς Κολοσσαεῖς | Epistola ad Colossenses | Col | C | |

| First Thessalonians | Church at Thessalonica | Πρὸς Θεσσαλονικεῖς Αʹ | Epistola I ad Thessalonicenses | 1 Thess | 1Th | |

| Second Thessalonians | Church at Thessalonica | Πρὸς Θεσσαλονικεῖς Βʹ | Epistola II ad Thessalonicenses | 2 Thess | 2Th | |

| First Timothy | Saint Timothy | Πρὸς Τιμόθεον Αʹ | Epistola I ad Timotheum | 1 Tim | 1T | |

| Second Timothy | Saint Timothy | Πρὸς Τιμόθεον Βʹ | Epistola II ad Timotheum | 2 Tim | 2T | |

| Titus | Saint Titus | Πρὸς Τίτον | Epistola ad Titum | Tit | T | |

| Philemon | Saint Philemon | Πρὸς Φιλήμονα | Epistola ad Philemonem | Philem | P | |

| Hebrews* | Hebrew Christians | Πρὸς Έβραίους | Epistola ad Hebraeus | Heb | H | |

This ordering is remarkably consistent in the manuscript tradition, with very few deviations. The evident principle of organization is descending length of the Greek text, but keeping the four Pastoral epistles addressed to individuals in a separate final section. The only anomaly is that Galatians precedes the slightly longer Ephesians.[5]

In modern editions, the formally anonymous Epistle to the Hebrews is placed at the end of Paul's letters and before the General epistles. This practice was popularized through the 4th century Vulgate by Jerome, who was aware of ancient doubts about its authorship, and is also followed in most medieval Byzantine manuscripts with hardly any exceptions.[5]

The placement of Hebrews among the Pauline epistles is less consistent in the manuscripts:

- between Romans and 1 Corinthians (i.e., in order by length without splitting the Epistles to the Corinthians): Papyrus 46 and minuscules 103, 455, 1961, 1964, 1977, 1994.

- between 2 Corinthians and Galatians: minuscules 1930, 1978, and 2248

- between Galatians and Ephesians: implied by the numbering in B. However, in B, Galatians ends and Ephesians begins on the same side of the same folio (page 1493); similarly 2 Thessalonians ends and Hebrews begins on the same side of the same folio (page 1512).[6]

- between 2 Thessalonians and 1 Timothy (i.e., before the Pastorals): א, A, B, C, H, I, P, 0150, 0151, and about 60 minuscules (e.g. 218, 632)

- after Philemon: D, 048, E, K, L and the majority of minuscules.

- omitted: F and G

Authenticity

| 36 | (31–36 AD: conversion of Paul) |

|---|---|

| 37 | |

| 38 | |

| 39 | |

| 40 | |

| 41 | |

| 42 | |

| 43 | |

| 44 | |

| 45 | |

| 46 | |

| 47 | |

| 48 | |

| 49 | |

| 50 | First Epistle to the Thessalonians |

| 51 | Second Epistle to the Thessalonians |

| 52 | |

| 53 | Epistle to the Galatians |

| 54 | First Epistle to the Corinthians |

| 55 | Epistle to the Philippians |

| Epistle to Philemon | |

| 56 | Second Epistle to the Corinthians |

| 57 | Epistle to the Romans |

| 58 | |

| 59 | |

| 60 | |

| 61 | |

| 62 | Epistle to the Colossians |

| Epistle to the Ephesians | |

| 63 | |

| 64 | First Epistle to Timothy |

| Second Epistle to Timothy | |

| Epistle to Titus | |

| 65 | |

| 66 | |

| 67 | (64–67 AD: death of Paul) |

In all of these epistles except the Epistle to the Hebrews, the author and writer does claim to be Paul. However, the contested letters may have been written using Paul's name, as it was common to attribute at that point in history.[7]

Seven letters (with consensus dates)[8] considered genuine by most scholars:

- First Thessalonians (c. 50 AD)

- Galatians (c. 53)

- First Corinthians (c. 53–54)

- Philippians (c. 55)

- Philemon (c. 55)

- Second Corinthians (c. 55–56)

- Romans (c. 57)

The letters on which scholars are about evenly divided:[2]

- Colossians (c. 62)

- Second Thessalonians (c. 49–51)

The letters thought to be pseudepigraphic by many scholars (traditional dating given):[2]

- Ephesians (c. 62)

- First Timothy (c. 62–64)

- Second Timothy (c. 62–64)

- Titus (c. 62–64)

Finally, Epistle to the Hebrews, though anonymous and not really in the form of a letter, has long been included among Paul's collected letters. Although some churches ascribe Hebrews to Paul,[9] neither most of Christianity nor modern scholarship do so.[2][10]

Lost Pauline epistles

Paul's own writings are often thought to indicate several of his letters that have not been preserved:

- A first epistle to Corinth,[11] referenced at 1 Corinthians 5:9

- A third epistle to Corinth, also called the Severe Letter, referenced at 2 Corinthians 2:4 and 2 Corinthians 7:8–9

- An earlier epistle to the Ephesians referenced at Ephesians 3:3–4

- The Epistle to the Laodiceans,[12] referenced at Colossians 4:16

Collected epistles

Robert M. Price asserts that the first collection of the Pauline epistles was that of Marcion of Sinope in the early 2nd century.[13] On the other hand, David Trobisch finds it likely that Paul first collected his letters for publication himself.[14] It was normal practice in Paul's time for letter-writers to keep one copy for themselves and send a second copy to the recipient(s); surviving collections of ancient letters sometimes originated from the senders' copies, other times from the recipients' copies.[15] A collection of Paul's letters circulated separately from other early Christian writings and later became part of the New Testament. When the canon was established, the gospels and Paul's letters were the core of what would become the New Testament.[14]

References

- The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, publ. Geoffrey Chapman, 1989, chapter 60, at p. 920, col. 2 "That Paul is neither directly nor indirectly the author is now the view of scholars almost without exception. For details, see Kümmel, I[ntroduction to the] N[ew] T[estament, Nashville, 1975] 392–94, 401–03"

- New Testament Letter Structure, from Catholic Resources by Felix Just, S.J.

- Richards, E. Randolph. Paul and First-Century Letter Writing: Secretaries, Composition and Collection. Downers Grove, IL; Leicester, England: InterVarsity Press; Apollos, 2004.

- Metzger, Bruce M. (1987). The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (PDF). pp. 295–96. ISBN 0198261802. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-01.

- Trobisch 1994, p. 1–27.

- Digital Vatican Library (DigiVatLib), Manuscript – Vat.gr.1209

- Joseph Barber Lightfoot in his Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians writes: "At this point [Gal 6:11] the apostle takes the pen from his amanuensis, and the concluding paragraph is written with his own hand. From the time when letters began to be forged in his name (2 Thess 2:2; 3:17) it seems to have been his practice to close with a few words in his own handwriting, as a precaution against such forgeries... In the present case he writes a whole paragraph, summing up the main lessons of the epistle in terse, eager, disjointed sentences. He writes it, too, in large, bold characters (Gr. pelikois grammasin), that his handwriting may reflect the energy and determination of his soul."

- Robert Wall, New Interpreter's Bible Vol. X (Abingdon Press, 2002), pp. 373.

- Arhipov, Sergei, ed. (1996). The Apostol. New Canaan, PA: St. Tikhon's Seminary Press. p. 408. ISBN 1-878997-49-1.

- Ellingworth, Paul (1993). The New International Greek Testament Commentary: The Epistle to the Hebrews. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eardmans Publishing Co. p. 3.

- Also called A Prior Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-06-23. Retrieved 2006-06-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) or Paul’s previous Corinthian letter., possibly Third Epistle to the Corinthians

- "Apologetics Press – Are There Lost Books of the Bible?". apologeticspress.org.

- Price, Robert M. "The Evolution of the Pauline Canon". The Journal of Higher Criticism. The Institute for Higher Critical Studies, Drew University. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

But the first collector of the Pauline Epistles had been Marcion

- Trobisch, David (1994). Paul’s Letter Collection. Minneapolis: Fortress. ISBN 9780800625979.

- Reece, Steve. Paul's Large Letters: Pauline Subscriptions in the Light of Ancient Epistolary Conventions. London: T&T Clark, 2016.

Bibliographic resources

- Aland Kurt. “The Problem of Anonymity and Pseudonymity in Christian Literature of the First Two Centuries.” Journal of Theological Studies 12 (1961): 39–49.

- Bahr, Gordon J. “Paul and Letter Writing in the First Century.” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 28 (1966): 465–77. idem, “The Subscriptions in the Pauline Letters.” Journal of Biblical Literature 2 (1968): 27–41.

- Bauckham, Richard J. “Pseudo-Apostolic Letters.” Journal of Biblical Literature 107 (1988): 469–94.

- Carson, D.A. “Pseudonymity and Pseudepigraphy.” Dictionary of New Testament Background. Eds. Craig A. Evans and Stanley E. Porter. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2000. 857–64.

- Cousar, Charles B. The Letters of Paul. Interpreting Biblical Texts. Nashville: Abingdon, 1996.

- Deissmann, G. Adolf. Bible Studies. Trans. Alexander Grieve. 1901. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1988.

- Doty, William G. Letters in Primitive Christianity. Guides to Biblical Scholarship. New Testament. Ed. Dan O. Via, Jr. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1988.

- Gamble, Harry Y. “Amanuensis.” Anchor Bible Dictionary. Vol. 1. Ed. David Noel Freedman. New York: Doubleday, 1992.

- Haines-Eitzen, Kim. “‘Girls Trained in Beautiful Writing’: Female Scribes in Roman Antiquity and Early Christianity.” Journal of Early Christian Studies 6.4 (1998): 629–46.

- Kim, Yung Suk. A Theological Introduction to Paul's Letters. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2011.

- Longenecker, Richard N. “Ancient Amanuenses and the Pauline Epistles.” New Dimensions in New Testament Study. Eds. Richard N. Longenecker and Merrill C. Tenney. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1974. 281–97. idem, “On the Form, Function, and Authority of the New Testament Letters.” Scripture and Truth. Eds. D.A. Carson and John D. Woodbridge. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1983. 101–14.

- Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome. Paul the Letter-Writer: His World, His Options, His Skills. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 1995.

- Richards, E. Randolph. The Secretary in the Letters of Paul. Tübingen: Mohr, 1991. idem, “The Codex and the Early Collection of Paul’s Letters.” Bulletin for Bulletin Research 8 (1998): 151–66. idem, Paul and First-Century Letter Writing: Secretaries, Composition, and Collection. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2004.

- Robson, E. Iliff. “Composition and Dictation in New Testament Books.” Journal of Theological Studies 18 (1917): 288–301.

- Stowers, Stanley K. Letter Writing in Greco-Roman Antiquity. Library of Early Christianity. Vol. 8. Ed. Wayne A. Meeks. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1989.

- Wall, Robert W. “Introduction to Epistolary Literature.” New Interpreter’s Bible. Vol. 10. Ed. Leander E. Keck. Nashville: Abingdon, 2002. 369–91.

- Hart, David Bentley. "The New Testament." New Haven and London: Yale University Press: 2017. 570–74.