History of Eurasia

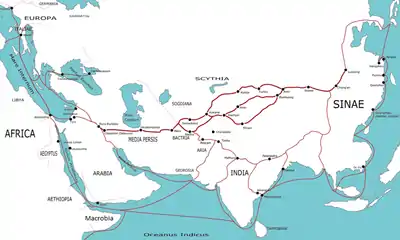

The history of Eurasia is the collective history of a continental area with several distinct peripheral coastal regions: the Middle East, South Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and Western Europe, linked by the interior mass of the Eurasian steppe of Central Asia and Eastern Europe. Perhaps beginning with the Steppe Route trade, the early Silk Road, the Eurasian view of history seeks establishing genetic, cultural, and linguistic links between Eurasian cultures of antiquity. Much interest in this area lies with the presumed origin of the speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language and chariot warfare in Central Eurasia.[1]

Prehistory

Lower Paleolithic

Fossilized remains of Homo ergaster and Homo erectus between 1.8 and 1.0 million years old have been found in Europe (Georgia (Dmanisi), Spain), Indonesia (e.g., Sangiran and Trinil), Vietnam, and China (e.g., Shaanxi). (See also:Multiregional hypothesis.) The first remains are of Olduwan culture, later of Acheulean and Clactonian culture. Finds of later fossils, such as Homo cepranensis, are local in nature, so the extent of human residence in Eurasia during 1,000,000 - 300,000 ybp remains a mystery.

Middle Paleolithic

Geologic temperature records indicate two intense ice ages dated around 650000 ybp and 450000 ybp. These would have presented any humans outside the tropics unprecedented difficulties. Indeed, fossils from this period are very few, and little can be said of human habitats in Eurasia during this period. The few finds are of Homo antecessor and Homo heidelbergensis, and Lantian Man in China.

After this, Homo neanderthalensis, with his Mousterian technology, emerged, in areas from Europe to western Asia and continued to be the dominant group of humans in Europe and the Middle East up until 40000-28000 ybp. Peking man has also been dated to this period. During the Eemian Stage, humans probably (e.g. Wolf Cave) spread wherever their technology and skills allowed. The Sahara dried up, forming a difficult area for peoples to cross.

The birth of the first modern humans (Homo sapiens idaltu) has been dated between 200000 and 130000 ybp (see:Mitochondrial Eve, Single-origin hypothesis), that is, to the coldest phase of the Riss glaciation. Remains of Aterian culture appear in the archaeological evidence.

Population bottleneck

In the beginning of the last ice age a supervolcano erupted in Indonesia. Theory states the effects of the eruption caused global climatic changes for many years, effectively obliterating most of the earlier cultures. Y-chromosomal Adam (90000 - 60000 BP, dated data) was initially dated here. Neanderthals survived this abrupt change in the environment, so it's possible for other human groups too. According to the theory humans survived in Africa, and began to resettle areas north, as the effects of the eruption slowly vanished. Upper Paleolithic revolution began after this extreme event, the earliest finds are dated c.50000 BCE.

A divergence in genetical evidence occurs during the early phase of the glaciation. Descendants of female haplogroups M, N and male CT are the ones found among Eurasian peoples today.

Upper Paleolithic

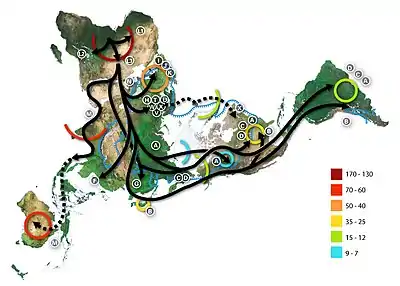

The Southern Dispersal scenario postulates the arrival of anatomically modern humans to Eurasia beginning about 70,000 BC. Moving along the southern coast of Asia, they reached Maritime Southeast Asia by about 65,000 years ago. The establishment of population centers in Western Asia, the Indian subcontinent and in East Asia is attested by about 50,000 years ago. The Eurasian Upper Paleolithic proper is taken after c. 45,000 years ago, with the Cro-Magnon expansion of into Europe (Mousterian), and the expansion into the Mammoth steppe of Northern Asia.

Migrations

Tracing back minute differences in the genomes of modern humans by methods of genetic genealogy, can and have been used to produce models of historical migration. Though these give indications of the routes taken by ancestral humans, the dating of the various genetic markers is improving. The earliest migrations (dated c. 75.000 BP) from the Red Sea shores have been most likely along southern coast of Asia. After this, tracking and timing genetical markers gets increasingly difficult. What is known, is that on areas, of what is now Iraq, Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan, genetic markers diversify (from about 60000 BCE), and subsequent migrations emerge to all directions (even back to the Levant) and North Africa. From the foothills of the Zagros, big game hunting cultures developed which spread across the Eurasian steppe. Crossing the Caucasus and the Ural Mountains were the ancestors of Samoyeds and the ancestors of Uralic peoples, developing sleds, skis and canoes. Through Kazakhstan moved the ancestors of the Indigenous Americans (dated 50000 - 40000 BCE). Eastbound (maybe through Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin went the ancestors of the northern Chinese and Koreans. It is possible that the routes taken by the Indo-European ancestors travelled across the Bosphorus. Genetic evidence suggests a number of separate migrations (1.Anatoleans 2. Tocharians, 3 Celto-Illyrians, 4.Germanic and Slav, - possibly in this order). Archaeological evidence has not been identified for a number of different groups. On historical linguistic evidence, see for example classification of Thracian. The traditional view of associating early Celts with the Hallstatt culture, and the Nordic Bronze Age with Germanic peoples. The Roman Empire spread after the first widespread use of iron outside Central Europe from the Villanovan culture area. Most likely there was trade also in these periods, e.g. with amber and salt being major products.

Influences from northern Africa via Gibraltar and Sicilia cannot be readily discounted. Many other questions remain open, too; for example, Neanderthals were still present at this time. More genetic data is being gathered by various research programs.

Early Holocene

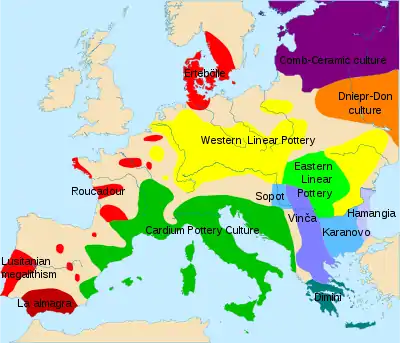

As the ice age ended, major environmental changes happened, such as sea level rise (est. 120m), vegetation changes, and animals disappearing in the Holocene extinction event. At the same time Neolithic revolution began and humans started to make pottery, began to cultivate crops and domesticated some animal species.

Neolithic cultures in Eurasia are many, and best discussed in separate articles. Some of the articles on this subject include: Natufian culture, Jōmon culture, List of Neolithic cultures of China and Mehrgarh. European sites are many, they are discussed in Prehistoric Europe. The finding of Ötzi the Iceman (dated 3300 BC) provides an important insight to Chalcolithic period in Europe. Proto-languages of various peoples have been forming in this period, though no literal evidence can (by definition) be found. Later migrations further complicate the study of migrations in this period.

Writing, the civilizations emerge

Origins of writing are dated to fourth millennium BC. Writing may have started independently on various areas of Eurasia. It appears the skill spread relatively fast, giving people a new way of communication.

The three regions of Western, Eastern and Southern Asia developed in a similar manner with each of the three regions developing early civilizations around fertile river valleys. The civilizations in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and China (along the Yellow River and the Yangtze) shared many similarities and likely exchanged technologies and ideas such as mathematics and the wheel. Ancient Egypt also shared this model. These civilizations were most likely in more or less regular contact with each other by the early versions of the silk road.

Europe was different, however. It was somewhat further north and contained no river systems to support agriculture. Thus Europe remained comparatively undeveloped, with only the southern tips of the region (Greece and Italy) being able to fully borrow crops, technologies, and ideas from the Middle East and North Africa. Similarly, civilization didn't arise in Southeast Asia until contact was made with ancient India, which gave rise to Indianized kingdoms in Indochina and the Malay archipelago. The steppe region had long been inhabited by mounted nomads, and from the central steppes they could reach all areas of the Asian continent. The northern part of the silk road traversed this region.

One such central expansion out of the steppe is that of the Proto-Indo-Europeans which spread their languages into the Middle East, India, Europe, and to the borders of China (with the Tocharians). Throughout their history, up to the development of gunpowder, all the areas of Eurasia would be repeatedly menaced by the Indo-Iranian, Turkic and Mongol nomads from the steppe.

A difference between Europe and most of the regions of Eurasia is that each of the latter regions has few obstructions internally even though it is ringed by mountains and deserts. This meant that it was easier to establish unified control over the entire region, and this did occur with massive empires consistently dominating the Middle East, China, and at times, much of India. Europe, however, is riddled with internal mountain ranges: The Carpathians, the Alps, the Pyrenees and many others. Throughout its history, Europe has thus usually been divided into many small states, much like the Middle East and Indian subcontinent for much of their history.

The Iron Age made large stands of timber essential to a nation's success because smelting iron required so much fuel, and the pinnacles of human civilizations gradually moved as forests were destroyed. In Europe the Mediterranean region was supplanted by the German and Frankish lands. In the Middle East the main power center became Anatolia with the once dominant Mesopotamia its vassal. In China, the economical, agricultural, and industrial center moved from the northern Yellow River to the southern Yangtze, though the political center remained in the north. In part this is linked to technological developments, such as the mouldboard plough, that made life in once undeveloped areas more bearable.

The civilizations in China, India, and Mediterranean, connected by the silk road, became the principal civilizations in Eurasia in early CE times. Later development of Eurasian history of mankind is told in other articles.

References

- Beckwith, for instance, gives an overall view of Central Eurasian history

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009): Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

- Schafer, Edward H. The Golden Peaches of Samarkand. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985 (1963). ISBN 978-0-520-05462-2.

See also

External links

Media related to History of Eurasia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of Eurasia at Wikimedia Commons