Maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia (as opposed to mainland Southeast Asia) comprises the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor.[1] Maritime Southeast Asia is sometimes also referred to as Island Southeast Asia, Insular Southeast Asia or Oceanic Southeast Asia. The 16th-century term "East Indies" and the later 19th-century term "Malay Archipelago" are also used to refer to maritime Southeast Asia.

In Indonesia and Malaysia, the Old Javanese term "Nusantara" is also used as a synonym for Maritime Southeast Asia. The term, however, is nationalistic and has shifting boundaries. It usually only encompasses the Malay Peninsula, the Sunda Islands, Maluku, and often Western New Guinea; excluding the Philippines and Papua New Guinea.[2][3]

Stretching for several thousand kilometres, the area features a very large number of islands and boasts some of the richest marine, flora and fauna biodiversity on Earth.

The main demographic difference that sets Maritime Southeast Asia apart from modern Mainland Southeast Asia is that its population predominantly belongs to Austronesian groups. The region contains some of the world's most highly urbanized areas: Greater Jakarta, Metro Manila, Greater Kuala Lumpur and Singapore; and yet a majority of islands in this vast region remain uninhabited by humans.

Geography

The land and sea area of Maritime Southeast Asia exceeds 2 million km2.[4] These are more than 25,000 islands of the area that comprise many smaller archipelagoes.[5]

The major groupings are:

- Singapore, Indonesia, East Malaysia and Brunei

- Philippines

- New Guinea and surrounding islands (when included)

The seven largest islands are New Guinea, Borneo, Sumatra, Sulawesi and Java in Indonesia; and Luzon and Mindanao in the Philippines.

In the natural sciences, the region is sometimes known as the Maritime Continent. It also corresponds to the biogeographical region of Malesia (not to be confused with "Malaysia"), with shared tropical flora and fauna.

Geologically, the archipelago is one of the most active volcanic regions in the world, producing many volcanoes, especially in Java, Sumatra and the Lesser Sunda Islands region, where most volcanoes over 3,000 m (9,843 ft) are situated. Tectonic uplifts also produced large mountains, including the highest in Mount Kinabalu in Sabah, Malaysia, with a height of 4,095.2 m and Puncak Jaya on Papua, Indonesia at 4,884 m (16,024 ft). Other high mountains in the archipelago include Puncak Mandala, Indonesia at 4,760 m (15,617 ft) and Puncak Trikora, Indonesia, at 4,750 m (15,584 ft).

The climate throughout the archipelago is tropical, owing to its position on the equator.

Culture and demographics

As of 2017, there were over 540 million people live in the region, with the most populated island being Java. The people living there are predominantly from Austronesian subgroupings and correspondingly speak western Malayo-Polynesian languages. This region of Southeast Asia shares social and cultural ties with both the peoples of mainland Southeast Asia and with other Austronesian peoples in the Pacific. Islam is the predominant religion, with Christianity being the dominant religion in the Philippines and East Timor. Buddhism, Hinduism, and traditional Animism are also practiced among large populations.

Historically, the region has been referred to as part of Greater India, as seen in Coedes' Indianized States of Southeast Asia, which refers to it as "Island Southeast Asia";[6] and within Austronesia or Oceania, due to shared ethnolinguistic and historical origins of the latter groups (Micronesian and Polynesian groups) being from this region.[7]

History

The maritime connectivity within the region has been linked to a it becoming a distinct cultural and economic area, when compared to the 'mainland' societies in the rest of Southeast Asia.[8] This region stretches from the Yangtze delta in China down to the Malay Peninsula, including the South China Sea, Gulf of Thailand and Java Sea. The region was dominated by the thalassocratic cultures of the Austronesian peoples.[9][10][11]

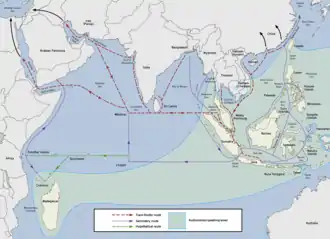

Ancient Indian Ocean trade

The first true maritime trade network in the Indian Ocean was by the Austronesian peoples of Island Southeast Asia,[9] who built the first ocean-going ships.[12] They established trade routes with Southern India and Sri Lanka as early as 1500 BC, ushering an exchange of material culture (like catamarans, outrigger boats, lashed-lug and sewn-plank boats, and paan) and cultigens (like coconuts, sandalwood, bananas, and sugarcane); as well as connecting the material cultures of India and China. Indonesians, in particular were trading in spices (mainly cinnamon and cassia) with East Africa using catamaran and outrigger boats and sailing with the help of the Westerlies in the Indian Ocean. This trade network expanded to reach as far as Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, resulting in the Austronesian colonization of Madagascar by the first half of the first millennium AD. It continued up to historic times.[9][13][11][14][15]

Maritime Silk Road

The ancient Austronesian trade networks was later used by the first Chinese trading fleets of the Song Dynasty at around 900 AD. It led to a renewed flourishing of trade between China and Southeast Asia, now known as the Maritime Silk Road. Demand for Southeast Asian products and trade was partially driven by the increase in China’s population in this era, whereby it doubled from 75 to 150 million.[16]

Trade with China ceased after the collapse of the Song Dynasty due to invasions and famine. It was restored during the Ming Dynasty from the 14th to 16th centuries.[17] The naval expeditions of Zheng He between 1405 and 1431 also played a critical role in opening up of China to increased trade with Southeast Asian polities.[18]

Chinese trade was strictly controlled by the Imperial Court, but the Hokkien diaspora facilitated informal trade and cultural exchange with Southeast Asia, settling among Southeast Asian polities during this time period. Despite not having the official sanction of the Chinese government these communities formed business and trade networks between cities such as Melaka, Hội An and Ayutthaya.[19][20] Many of these Chinese businesspeople integrated into their new countries, becoming political officials and diplomats.[21]

See also

References

- Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge history of Southeast Asia, Volume 1, Part 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-521-66369-4.; RAND Corporation. (PDF); Shaffer, Lynda (1996). Maritime Southeast Asia to 1500. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-1-56324-144-4.; Ciorciar, John David (2010). The Limits of Alignment: Southeast Asia and the Great Powers Since 197. Georgetown Univeffrsity Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-1589016262.; Nichiporuk, Brian; Grammich, Clifford; Rabasa, Angel; DaVanzo, Julie (2006). "Demographics and Security in Maritime Southeast Asia". Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. 7 (1): 83–91.

- Evers, Hans-Dieter (2016). "Nusantara: History of a Concept". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 89 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1353/ras.2016.0004. S2CID 163375995.

- Gaynor, Jennifer L. (2007). "Maritime Ideologies and Ethnic Anomalies". In Bentley, Jerry H.; Bridenthal, Renate; Wigen, Kären (eds.). Seascapes: Maritime Histories, Littoral Cultures, and Transoceanic Exchanges. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 59–65. ISBN 9780824830274.

- Moores, Eldridge M.; Fairbridge, Rhodes Whitmore (1997). Encyclopedia of European and Asian regional geology. Springer. p. 377. ISBN 0-412-74040-0. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- Philippines : General Information. Government of the Philippines. Retrieved 2009-11-06; "World Economic Outlook Database" (Press release). International Monetary Fund. April 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-05.; "Indonesia Regions". Indonesia Business Directory. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- Coedes, G. (1968) The Indianized States of Southeast Asia Edited by Walter F. Vella. Translated by Susan Brown Cowing. Canberra: Australian National University Press. Introduction... The geographic area here called Farther India consists of Indonesia, or island Southeast Asia....

- See the cultural macroregions of the world table below.

- Sutherland, Heather (2003). "Southeast Asian History and the Mediterranean Analogy" (PDF). Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 34 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1017/S0022463403000018. JSTOR 20072472.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN 9783319338224.

- Brides of the sea : port cities of Asia from the 16th-20th centuries. Broeze, Frank. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. 1989. ISBN 978-0824812669. OCLC 19554419.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 0415100542.

- Meacham, Steve (11 December 2008). "Austronesians were first to sail the seas". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- Doran, Edwin, Jr. (1974). "Outrigger Ages". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 83 (2): 130–140.

- Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961070.

- Blench, Roger (2004). "Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 24 (The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50.

- 1945-, Lieberman, Victor B. (2003–2009). Strange parallels : Southeast Asia in global context, c 800-1830. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521800860. OCLC 49820972.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Sen, Tansen (2006). "The Formation of Chinese Maritime Networks to Southern Asia, 1200-1450". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 49 (4): 421–453. doi:10.1163/156852006779048372. JSTOR 25165168.

- 1939-, Reid, Anthony (1988–1993). Southeast Asia in the age of commerce, 1450-1680. Rogers D. Spotswood Collection. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300039214. OCLC 16646158.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- YOKKAICHI, Yasuhiro. "Chinese and Muslim Diasporas and Indian Ocean Trade under the Mongol Hegemony". Angela Schottenhammer[ed.] the East Asian Mediterranean : Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce, and Human Migration. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Lockard, Craig A. (2010-08-01). ""The Sea Common to All": Maritime Frontiers, Port Cities, and Chinese Traders in the Southeast Asian Age of Commerce, ca. 1400–1750". Journal of World History. 21 (2): 219–247. doi:10.1353/jwh.0.0127. ISSN 1527-8050. S2CID 162282960.

- Sojourners and settlers : histories of Southeast Asia and the Chinese. Reid, Anthony, 1939-, Alilunas-Rodgers, Kristine. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. 2001. ISBN 978-0824824464. OCLC 45791365.CS1 maint: others (link)

External links

- Art of Island Southeast Asia, a full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art