Turkic migration

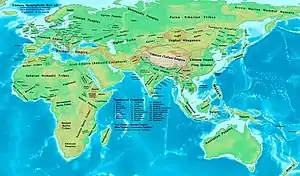

Turkic migration refers to the spread of Turkic tribes and Turkic languages across Eurasia and between the 6th and 11th centuries. In the 6th century, the Göktürks overthrew the Rouran Khaganate in what is now Mongolia and expanded in all directions, spreading Turkic culture throughout the Eurasian steppes. Although Göktürk empires came to an end in the 8th century, they were succeeded by numerous Turkic empires such as the Uyghur Khaganate, Kara-Khanid Khanate, Khazars, and the Cumans. Some Turks eventually settled down into a sedentary society such as the Qocho and Ganzhou Uyghurs. The Seljuq dynasty settled in Anatolia starting in the 11th century, resulting in permanent Turkic settlement and presence there. Modern nations with large Turkic populations include Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, and Turkic populations also exist within other nations, such as Chuvashia, Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, the Crimean Tatars, the Uyghurs in China, and the Sakha Republic Siberia.

Origin theories

Proposals for the homeland of the Turkic peoples and their language are far-ranging, from the Transcaspian steppe to Northeastern Asia (Manchuria).[1] According to Yunusbayev et al. (2015), genetic evidence points to an origin in the region near South Siberia and Mongolia as the "Inner Asian Homeland" of the Turkic ethnicity.[2] Similarly several linguists, including Juha Janhunen, Roger Blench and Matthew Spriggs, suggest that Mongolia is the homeland of the early Turkic language.[3] According to Robbeets, the Turkic people descend from people who lived in a region extending from present-day South Siberia and Mongolia to the West Liao River Basin (modern Manchuria).[4] Authors Joo-Yup Lee and Shuntu Kuang analyzed 10 years of genetic research on Turkic people and compiled scholarly information about Turkic origins, and said that the early and medieval Turks were a heterogeneous group and that the Turkification of Eurasia was a result of language diffusion, not a migration of a homogeneous population.[5]

Hunnic theory

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe, between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part of Scythia at the time; the Huns' arrival is associated with the migration westward of an Indo-Iranian people, the Alans.[6] The Huns have often been considered a Turkic people, and sometimes associated with the Xiongnu. While in Europe, the Huns incorporated others, such as Goths, Slavs, and Alans.

The Huns were not literate (according to Procopius[7]) and left nothing linguistic with which to identify them except their names,[7] which derive from Germanic, Iranian, Turkic, unknown and a mixture.[8] Some, such as Ultinčur and Alpilčur, are like Turkish names ending in -čor, Pecheneg names in -tzour and Kirghiz names in -čoro. Names ending in -gur, such as Utigur and Onogur, and -gir, such as Ultingir, are like Turkish names of the same endings.

The actual identity of the Huns is still debated. Concerning the cultural genesis of the Huns, the Cambridge Ancient History of China asserts: "Beginning in about the eighth century BC, throughout inner Asia horse-riding pastoral communities appeared, giving origin to warrior societies." These were part of a larger belt of "equestrian pastoral peoples" stretching from the Black Sea to Mongolia, and known to the Greeks as the Scythians.[9]

Göktürk wave (5th-8th c.)

Tiele and Turk

The earliest Turks mentioned in textual sources are the Tiele people (鐵勒), a transcription of the endonym *Tegreg "[People of the] Carts",[10] recorded by the Chinese in the 6th century. According to the New Book of Tang, Tiele is just a mistaken form of Chile/Gaoche, who themselves are just the Xiongnu branch of the Dingling people. Many scholars believe the Di, Dili, Dingling, and later Tujue mentioned in textual sources are all just Chinese transcriptions of the same Turkic word.[11]

The first reference to Türk or Türküt appears in 6th century Chinese sources as the transcription Tūjué (突厥). The earliest evidence of Turkic languages and the use of "Turk" as an endonym comes from the Orkhon inscriptions of the Göktürks (English: 'Celestial Turks') in the early 8th century. Many groups speaking 'Turkic' languages never adopted the name "Turk" for their own identity. Among the peoples that came under Göktürk dominance and adopted its political culture and lingua-franca, the name "Turk" wasn't always the preferred identity. Turk therefore did not apply to all Turkic peoples at the time, but only referred to the Eastern Turkic Khaganate, while the Western Turkic Khaganate and Tiele used their own tribal names. Of the Tiele, the Book of Sui mentions only tribes which were not part a part of the First Turkic Khaganate.[12] There wasn't a unified expansion of Turkic tribes. Peripheral Turkic peoples in the Göktürk Empire like the Bulgars and even central ones like the Oghuz and Karluks migrated autonomously with migrating traders, soldiers and townspeople.

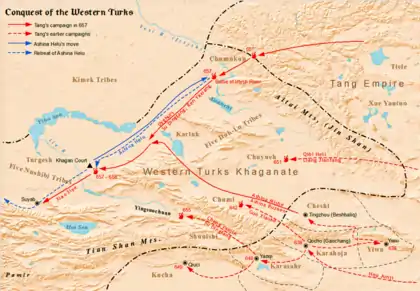

The precise date of the initial expansion from the early homeland remains unknown. The first state known as "Turk", giving its name to the many states and peoples afterwards, was that of the Göktürks (gök = 'blue' or 'celestial', however in this context "gök" refers to the direction "east". Therefore, Gokturks are the Eastern Turks) in the 6th century. In 439, the head of the Ashina clan led his people from Lijian (modern Zhelaizhai) to the Rouran seeking inclusion in their confederacy and protection from China. His tribe consisted of famed metal smiths and was granted land near a mountain quarry that looked like a helmet, from which they got their name Turk/Tujue 突厥. In 546, the leader of the Ashina, Bumin, aided the Rouran in putting down a Tiele revolt. Bumin requested a Rouran princess for his service but was denied, after which he declared independence. In 551, Bumin declared himself Khagan and married Princess Changle from Western Wei. He then dealt a serious blow to the Rouran Khaganate the next year, but died soon after. His sons, Issik Qaghan and Muqan Qaghan, continued to wage war on the Rouran, finishing them off in 554. By 568, their territory had reached the edges of the Byzantine Empire, where the Avars, possibly related to the Rouran in some fashion, escaped.[13] In 581, Taspar Qaghan died and the khaganate entered a civil war that resulted in two separate Turkic factions. The Eastern Khaganate was defeated by the Tang dynasty in 630 while the Western Khaganate fell to the Tang in 657. In 682, Ilterish Qaghan rebelled against the Tang and founded the Second Turkic Khaganate, which fell to the Uyghurs in 744.[14]

Bulgar

The Bulgars, also known as the Onogur-Bulgars or Onogundurs, arrived in the Kuban steppe zone sometime during the 5th century. By the 7th century, they were under the rule of the Avars, who they revolted against in 635 under the leadership of Kubrat. Prior to this, Kubrat had made an alliance with Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire. He was baptized in 619. Kubrat died in the 660s and his territory, Old Great Bulgaria, was divided between his sons. Two of them were incorporated by the Khazars, one headed to Pannonia, and one became a subject of the Byzantines. The Bulgars in Pannonia revolted against the Pannonian Avars and migrated to Thessalonika by 679. There they formed the First Bulgarian Empire.[15]

Khazar

The origin of the Khazars is unclear. Some believe they were originally part of the Uyghurs, some of whom migrated west prior to 555. According to Al-Masudi, the Khazars were called Sabirs in Turkic. Some believe the Khazars were founded by Irbis Seguy, the penultimate ruler of the Western Turkic Khaganate, since the Hudud al-'Alam says the Khazar king descended from the Ansa, which has been interpreted as Ashina. By the mid-7th century, the Khazars were located in the North Caucasus, where they fought against the Umayyads constantly.[16]

Kyrgyz

According to the Book of Tang, the Yenisei Kyrgyz were tall, red haired, blue eyed, and had ruddy faces. It also notes that Kyrgyz women outnumbered men, both men and women wore tattoos, and they made weapons which they gave to the Turks. They practiced agriculture but did not grow fruits. The Kyrgyz lived west of Lake Baikal and east of the Karluks. According to the Book of Sui, the Kyrgyz chaffed at the domination of the First Turkic Khaganate. The Uyghur Khaganate also made war on the Kyrgyz and cut them off from trade with China, which the Uyghurs monopolized. As a result, the Kyrgyz turned to other channels of trade such as with the Tibetans, Arabs, and Karluks. From 820 onward, the Kyrgyz were constantly at war with the Uyghurs, until 840, when the Uyghur Khaganate was dismantled. Although the Kyrgyz managed to occupy some of the Uyghur land, they had no great effect on the geopolitical configuration around them. The Chinese paid no heed to them other than to award them with some titles and reasoned that since the Uyghurs were no longer in power, there was no reason to maintain relations with the Kyrgyz any longer. The Kyrgyz themselves seemed to lack any interest in occupying the former territory of the Uyghurs in the east. By 924, the Khitans had occupied Otuken in the territory of the former Uyghur Khaganate.[17]

Turgesh

In 699, the Turgesh ruler Wuzhile founded a khaganate stretching from Chach to Beshbalik. He and his successor Saqal campaigned against the Tang dynasty and their Turkic allies until 711, when the resurgent Second Turkic Khaganate crushed the Turgesh in battle. Turgesh remnants under Suluk re-established themselves in Zhetysu. Suluk was killed by one of his subordinates in 737 after he was defeated by the Umayyads. The Tang took advantage of the situation to invade Turgesh territory and took the city of Suyab. In the 760s, the Karluks drove out the Turgesh.[18]

Karluk

The Karluks, who take their name from the Turkic word for snow, migrated into the area of Tokharistan as early as the 7th century.[19] In 744, they participated in the Uyghur Khaganate's rise by overthrowing the Second Turkic Khaganate, but conflict with the Uyghurs forced them to migrate further west into Zhetysu. By 766, they had pushed out the Turgesh and took the Western Turkic capital of Suyab. Islam began spreading in the Karluk tribes during the 9th century. According to the Hudud al-'Alam, written in the 10th century, the Karluks were pleasant nearly civilized people who participated in agriculture as well as herding and hunting. Al-Masudi considered the Karluks to be the most beautiful people among the Turks, being tall in stature, and lordly in appearance. By the 11th century, they had integrated a considerable number of Sogdians into their population, resulting in speech that to Mahmud al-Kashgari, sounded slurred. The Karluks, Chigils, and Yagmas formed the Kara-Khanid Khanate in the 9th century, but it's unclear whether the leadership of the new polity fell to the Karluks or the Yagmas.[20]

Pecheneg

According to the Book of Sui (7th century), the Pechenegs, known as the Beiru, lived among the Tiele and were neighbors of the Onoğurs and Alans in the steppes of modern Kazakhstan and the North Caucasus. An 8th century Tibetan translation of a Uyghur account says the Pechenegs warred with the Hephthalites. The Pecheneg tribes were possibly related to the Kankalis. In the late 9th century, conflict with the Khazars drove the Pechenegs into the Pontic steppes. In the 10th century they had substantial interactions with the Byzantine Empire, who depended on them for keeping control of their neighbors. Byzantine and Muslim sources confirm that the Pechenegs had a leader, but the position was not passed down from father to son. In the 10th century, the Pechenegs came into military conflict with the Rus', and in the early 11th century, military conflict with the Oghuz Turks drove them further west across the Danube into Byzantine territory.[21]

Uyghur wave (8th-9th c.)

Oghuz

The Oghuz Turks take their name from the Turkic word for "clan", "tribe", or "kinship". As such, Oghuz is a common appellation for many Turkic groups, such as the Toquz Oghuz (nine tribes), Sekiz Oghuz (eight tribes), and Uch Oghuz (three tribes). Oghuz has been used to refer to many different Turkic tribes, causing much confusion. For example, the ruler of the Oghuz was called the Toquz Khagan, even though there were 12 tribes instead of nine.[22] It's not certain if the Oghuz Turks were directly descended from the Toquz Oghuz. They may have been under the direct leadership of the Toquz at some point, but by the 11th century, the Oghuz were already linguistically distinct from their neighbors such as the Kipchaks and Karakhanids.[23]

The Oghuz migration westward began with the fall of the Second Turkic Khaganate and rise of the Uyghur Khaganate in 744. Under Uyghur rule, the Oghuz leader obtained the title of "right yabgu". When they appeared in Muslim textual sources in the 9th century, they were described using the same title. The Oghuz fought a series of wars with the Pechenegs, Khalaj, Charuk, and Khazars for the steppes, emerging victorious and establishing the Oghuz Yabgu State. The Oghuz were in constant conflict with the Pechenegs and Khazars throughout the 10th century, as recorded by Muslim texts, but they also cooperated at times. In one instance, the Khazars hired the Oghuz to fight off an attack by the Alans. In 965, the Oghuz took part in a Rus' attack on the Khazars and in 985 they joined the Rus' again in attacking Volga Bulgaria. The Yabgu State of the Oghuz did not have a central leadership and there is no evidence of the Yabgu acting as a spokesman for the entire Oghuz people. By the 10th century, some Oghuz had settled in towns and converted to Islam, although many tribes still followed Tengrism.[24]

Cuman Kipchak

The relationship and origins of the Cumans and Kipchaks is uncertain. They are sometimes considered the same people by different names: they were called Cumans in the West and Kipchaks in the East. The earliest mention of them comes from an inscription of Bayanchur Khan of the Uyghur Khaganate, which mentions the Turk-Kipchak. According to Rashid al-Din Hamadani, writing much later in the Ilkhanate, Kipchak is derived from a Turkic word which means "hollow rotted out tree". Cuman may be derived from the Turkic word qun, which means "pale" or "yellow". Some scholars associate the Cuman Kipchaks with the Kankalis.[25] The Kipchaks were next mentioned in the 9th century by Ibn Khordadbeh, who placed them next to the Toquz Oghuz, while Al-Biruni claimed that the Qun were further east of them. Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi writes that the Qun came from the lands of Cathay which they fled from in fear of the Khitans. This may have been what the Armenian chronicler Matthew of Edessa was referring to when he recounted Pale Ones being driven out by the people of the Snakes,[26] whom Golden identified as a Mongolic or para-Mongolic people known as Qay in Arabic, Tatabï in Old Turkic, and Kumo Xi in Chinese language.[27]

Kimek

In the mid-9th century, the Kimeks emerged in the northern steppes stretching from Lake Balkhash in the east to the Aral Sea in the west. They were originally a minor tribe who held the title of "Shad Tutuk", derived from the Chinese military title "Dudu", but started using the title of "Yabgu" instead when remnants of the Uyghur Khaganate fled to them in 840. By the early 10th century, the Kimeks bordered the Oghuz to the south, where the Ural formed the boundary. According to the Hudud al-'Alam, written in the 10th century, the Kimeks used the title of Khagan. They were the most removed from sedentary civilization of all the Turks and had only one town within their territory. In the 11th century, the Kimeks were displaced by the Cumans.[28]

Later Turkic peoples

_eng.png.webp)

Later Turkic peoples include the Khazars, Turkmens: either Karluks (mainly 8th century) or Oghuz Turks, Uyghurs, Yenisei Kyrgyz, Pechenegs, Cumans-Kipchaks, etc. As these peoples were founding states in the area between Mongolia and Transoxiana, they came into contact with Muslims, and most gradually adopted Islam. However, there were also some other groups of Turkic people who belonged to other religions, including Christians, Judaists, Buddhists, Manichaeans, and Zoroastrians.

Turkmens

While the Karakhanid state remained in this territory until its conquest by Genghis Khan, the Turkmen group of tribes was formed around the core of westward Oghuz. The name "Turkmen" originally simply meant "I am Turk" in the language of the diverse tribes living between the Karakhanid and Samanid states. Thus, the ethnic consciousness among some, but not all Turkic tribes as "Turkmens" in the Islamic era came long after the fall of the non-Muslim Gokturk (and Eastern and Western) Khanates. The name "Turk" in the Islamic era became an identity that grouped Islamized Turkic tribes in contradistinction to Turkic tribes that were not Muslim (that mostly have been referred to as "Tatar"), such as the Nestorian Naiman (which became a major founding stock for the Muslim Kazakh nation) and Buddhist Tuvans. Thus the ethnonym "Turk" for the diverse Islamized Turkic tribes somehow served the same function as the name "Tajik" did for the diverse Iranian peoples who converted to Islam and adopted Persian as their lingua-franca. Both names first and foremost labeled Muslimness, and to a lesser extent, common language and ethnic culture. Long after the departure of the Turkmens from Transoxiana towards the Karakum and Caucasus, consciousness associated with the name "Turk" still remained, as Chagatay and Timurid period Central Asia was called "Turkestan" and the Chagatay language called "Turki", even though the people only referred to themselves as "Mughals", "Sarts", "Taranchis" and "Tajiks". This name "Turk", was not commonly used by most groups of the Kypchak branch, such as the Kazakhs, although they are closely related to the Oghuz (Turkmens) and Karluks (Karakhanids, Sarts, Uyghurs). Neither did Bulgars (Kazan Tatars, Chuvash) and non-Muslim Turkic groups (Tuvans, Yakuts, Yugurs) come close to adopting the ethnonym "Turk" in its Islamic Era sense. Among the Karakhanid period Turkmen tribes rose the Atabeg Seljuq of the Kinik tribe, whose dynasty grew into a great Islamic empire stretching from India to Anatolia.

Turkic soldiers in the army of the Abbasid caliphs emerged as the de facto rulers of much of the Muslim Middle East (apart from Syria and North Africa) from the 13th century. The Oghuz and other tribes captured and dominated various countries under the leadership of the Seljuk dynasty, and eventually captured the territories of the Abbasid dynasty and the Byzantine Empire.

Meanwhile, the Kyrgyz and Uyghurs were struggling with one another and with the Chinese Empire. The Kyrgyz people ultimately settled in the region now referred to as Kyrgyzstan. The Batu hordes conquered the Volga Bulgars in what is today Tatarstan and Kypchaks in what is now Southern Russia, following the westward sweep of the Mongols in the 13th century. Other Bulgars settled in Europe in the 7-8th centuries, but were assimilated by the Slavs, giving the name to the Bulgarians and the Slavic Bulgarian language.

It was under Seljuq suzerainty that numerous Turkmen tribes, especially those that came through the Caucasus via Azerbaijan, acquired fiefdoms (beyliks) in newly conquered areas of Anatolia, Iraq and even the Levant. Thus, the ancestors of the founding stock of the modern Turkish nation were most closely related to the Oghuz Turkmen groups that settled in the Caucasus and later became the Azerbaijani nation.

By early modern times, the name "Turkestan" has several definitions:

- land of sedentary Turkic-speaking townspeople that have been subjects of the Central Asian Chagatayids, i.e. Sarts, Central Asian Mughals, Central Asian Timurids, Taranchi of Chinese Turkestan, and the later invading East Kipchak Tatars who mixed with local Sarts and Chagatais to form the Uzbeks; This area roughly coincides with "Khorasan" in the widest sense, plus Tarim Basin which was known as Chinese Turkestan. It is ethnically diverse, and includes homelands of non-Turkic peoples like the Tajiks, Pashtuns, Hazaras, Dungans, Dzungars. Turkic peoples of the Kypchak branch, i.e. Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, are not normally considered "Turkestanis" but are also populous (as pastoralists) in many parts of Turkestan.

- a specific district governed by a 17th-century Kazakh Khan, in modern-day Kazakhstan, which were more sedentary than other Kazakh areas, and were populated by towns-dwelling Sarts

See also

References

Citations

- Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg (2015-04-21). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLOS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

The origin and early dispersal history of the Turkic peoples is disputed, with candidates for their ancient homeland ranging from the Transcaspian steppe to Manchuria in Northeast Asia,

- Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg (2015-04-21). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLOS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

Thus, our study provides the first genetic evidence supporting one of the previously hypothesized IAHs to be near Mongolia and South Siberia.

- Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (2003-09-02). Archaeology and Language II: Archaeological Data and Linguistic Hypotheses. Routledge. ISBN 9781134828692.

- "Transeurasian theory: A case of farming/language dispersal". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2019-03-13.

- Lee (18 Oct 2017). Brill. 19 (2) https://brill.com/view/journals/inas/19/2/article-p197_197.xml. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Sinor 1990, p. 180.

- Maenchen-Helfen (1973) page 376.

- Maenchen-Helfen (1973) pages 441–442.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (1999). "The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C. Cambridge University Press. p. 886. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Ḡozz at Encyclopædia Iranica

- Cheng 2012, p. 83.

- Cheng 2012, p. 86.

- Gao Yang, "The Origin of the Turks and the Turkish Khanate", X. Türk Tarih Kongresi: Ankara 22 – 26 Eylül 1986, Kongreye Sunulan Bildiriler, V. Cilt, Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1991, s. 731. (in English)

- Barfield 1989, p. 150.

- Golden 1992, p. 244-246.

- Golden 1992, p. 233-238.

- Golden 1992, p. 176-183.

- Asimov 1988, p. 33.

- Bregel 2003, p. 16.

- Golden 1992, p. 198-199.

- Golden 1992, p. 264-268.

- Golden 1992, p. 205-206.

- Golden 1992, p. 207.

- Golden 1992, p. 209-211.

- Golden 1992, p. 270-272.

- Golden 1992, p. 274.

- Golden, Peter B. (2006) "Cumanica V: The Basmıls and the Qıpčaks" in Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 15. p. 16-24

- Golden 1992, p. 204-205.

Sources

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Cheng, Fangyi (2012), THE RESEARCH ON THE IDENTIFICATION BETWEEN TIELE (鐵勒) AND THE OΓURIC TRIBES

- Findley, Carter Vaughnm, The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press: Oxford (2005).

- Golden, Peter B. (1992), An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples

- Holster, Charles Warren, The Turks of Central Asia Praeger: Westport, Connecticut (1993).

- Sinor, Denis (1990). "The Hun Period". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Cambridge history of early Inner Asi a (1st. publ. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 177–203. ISBN 9780521243049.