History of rail transport in Great Britain

The railway system of Great Britain started with the building of local isolated wooden wagonways starting in the 1560s. A patchwork of local rail links operated by small private railway companies developed in the late 18th century. These isolated links expanded during the railway boom of the 1840s into a national network, although still run by dozens of competing companies. Over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries, these amalgamated or were bought by competitors until only a handful of larger companies remained (see railway mania). The entire network was brought under government control during the First World War and a number of advantages of amalgamation and planning were demonstrated. However, the government resisted calls for the nationalisation of the network. In 1923, almost all the remaining companies were grouped into the "Big Four": the Great Western Railway, the London and North Eastern Railway, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway and the Southern Railway. The "Big Four" were joint-stock public companies and they continued to run the railway system until 31 December 1947.

- This article is part of the history of rail transport by country series.

From the start of 1948, the "Big Four" were nationalised to form British Railways. Though there were few initial changes to services, usage increased and the network became profitable. Declining passenger numbers and financial losses in the late 1950s and early 1960s prompted the closure of many branch and main lines, and small stations, under the Beeching Axe. High-speed inter-city trains were introduced in the 1970s. The 1980s saw severe cuts in rail subsidies and above-inflation increases in fares, and losses decreased. Railway operations were privatised during 1994–1997. Ownership of the track and infrastructure passed to Railtrack, whilst passenger operations were franchised to individual private sector operators (originally there were 25 franchises) and the freight services were sold outright. Since privatisation, passenger volumes have increased to their highest ever level, but whether this is due to privatisation is disputed. The Hatfield accident set in motion a series of events that resulted in the ultimate collapse of Railtrack and its replacement with Network Rail, a state-owned, not-for-dividend company.

Before 1830: The pioneers

A wagonway, essentially a railway powered by animals drawing the cars or wagons, was used by German miners at Caldbeck, Cumbria, England, perhaps from the 1560s.[1] A wagonway was built at Prescot, near Liverpool, sometime around 1600, possibly as early as 1594. Owned by Philip Layton, the line carried coal from a pit near Prescot Hall to a terminus about half a mile away.[2]

Another wagonway was Sir Francis Willoughby's Wollaton Wagonway in Nottinghamshire built between 1603 and 1604 to carry coal.[3]

As early as 1671 railed roads were in use in Durham to ease the conveyance of coal; the first of these was the Tanfield Wagonway.[4] Many of these tramroads or wagon ways were built in the 17th and 18th centuries. They used simply straight and parallel rails of timber on which carts with simple flanged iron wheels were drawn by horses, enabling several wagons to be moved simultaneously. The first public railway in the world was the Lake Lock Rail Road, a narrow gauge railway built near Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England.[5][6][7]

Although the idea of wooden-railed wagonways originated in Germany in the 16th century, the first use of steam locomotives was in Britain. Its earliest "railways" were straight and were constructed from parallel rails of timber on which ran horse-drawn carts. These were succeeded in 1793 when Benjamin Outram constructed a mile-long tramway with L-shaped cast iron rails. These rails became obsolete when William Jessop began to manufacture cast iron rails without guiding ledges - the wheels of the carts had flanges instead. Cast iron is brittle and so the rails tended to break easily. Consequently, in 1820, John Birkenshaw introduced a method of rolling wrought iron rails, which were used from then onwards.

The first passenger-carrying public railway was opened by the Swansea and Mumbles Railway at Oystermouth in 1807, using horse-drawn carriages on an existing tramline.

In 1802, Richard Trevithick designed and built the first (unnamed) steam locomotive to run on smooth rails.[8]

.jpg.webp)

The first commercially successful steam locomotive was Salamanca, built in 1812 by John Blenkinsop and Matthew Murray for the 4 ft (1,219 mm) gauge Middleton Railway.[9] Salamanca was a rack and pinion locomotive, with cog wheels driven by two cylinders embedded into the top of the centre-flue boiler.

In 1813, William Hedley and Timothy Hackworth designed a locomotive (Puffing Billy) for use on the tramway between Stockton and Darlington.[10] Puffing Billy featured piston rods extending upwards to pivoting beams, connected in turn by rods to a crankshaft beneath the frames which, in turn, drove the gears attached to the wheels. This meant that the wheels were coupled, allowing better traction. A year later, George Stephenson improved on that design with his first locomotive Blücher,[11] which was the first locomotive to use single-flanged wheels.

That design persuaded the backers of the proposed Stockton and Darlington Railway to appoint Stephenson as Engineer for the line in 1821. While traffic was originally intended to be horse-drawn, Stephenson carried out a fresh survey of the route to allow steam haulage. The Act was subsequently amended to allow the usage of steam locomotives and also to allow passengers to be carried on the railway. The 25-mile (40 km) long route opened on 27 September 1825 and, with the aid of Stephenson's Locomotion No. 1, was the first locomotive-hauled public railway in the world.

1830 – 1922: Early development

In 1830 the Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened. This set the pattern for modern railways. It was the world's first inter-city passenger railway and the first to have 'scheduled' services, terminal stations and services as we know them today. The railways carried freight and passengers with also the world's first goods terminal station at the Park Lane railway goods station at Liverpool's south docks, accessed by the 1.26-mile Wapping Tunnel. In 1836, at the Liverpool end the line was extended to Lime Street station in Liverpool's city centre via a 1.1 mile long tunnel.

Many of the first public railways were built as local rail links operated by small private railway companies. With increasing rapidity, more and more lines were built, often with scant regard for their potential for traffic. The 1840s were by far the biggest decade for railway growth. In 1840, when the decade began, railway lines in Britain were few and scattered but, within ten years, a virtually complete network had been laid down and the vast majority of towns and villages had a rail connection and sometimes two or three. Over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries, most of the pioneering independent railway companies amalgamated or were bought by competitors, until only a handful of larger companies remained (see Railway Mania).

The period also saw a steady increase in government involvement, especially in safety matters. The 1840 "Act for Regulating Railways"[12] empowered the Board of Trade to appoint railway inspectors. The Railway Inspectorate was established in 1840, to enquire into the causes of accidents and recommend ways of avoiding them.[13] As early as 1844, a bill had been put before Parliament suggesting the state purchase of the railways; this was not adopted. It did, however, lead to the introduction of minimum standards for the construction of carriages[14] and the compulsory provision of 3rd class accommodation for passengers - so-called "Parliamentary trains".

The railway companies ceased to be profitable after the mid-1870s.[15] Nationalisation of the railways was first proposed by William Ewart Gladstone as early as the 1840s, and calls for nationalisation continued throughout that century, with F. Keddell writing in 1890 that "The only valid ground for maintaining the monopoly would be the proof that the Railway Companies have made a fair and proper use of their great powers, and have conduced to the prosperity of the people. But the exact contrary is the case."[16] The entire network was brought under government control during the First World War, and a number of advantages of amalgamation and planning were revealed. However, the Conservative members of the wartime coalition government resisted calls for the formal nationalisation of the railways in 1921.

1923 – 1947: The Big Four

On 1 January 1923, almost all the railway companies were grouped into the Big Four: the Great Western Railway, the London and North Eastern Railway, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway and the Southern Railway companies.[17] A number of other lines, already operating as joint railways, remained separate from the Big Four; these included the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway and the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway. The "Big Four" were joint-stock public companies and they continued to run the railway system until 31 December 1947.

The competition from road transport during the 1920s and 1930s greatly reduced the revenue available to the railways, even though the needs for maintenance on the network had never been higher, as investment had been deferred over the past decade. Rail companies accused the government of favouring road haulage through the construction of roads subsidised by the taxpayer, while restricting the rail industry's ability to use flexible pricing because it was held to nationally agreed rate cards. The government response was to commission several inconclusive reports; the Salter Report of 1933 finally recommended that road transport should be taxed directly to fund the roads and increased Vehicle Excise Duty and fuel duties were introduced. It also noted that many small lines would never be likely to compete with road haulage. Although these road pricing changes helped their survival, the railways entered a period of slow decline, owing to a lack of investment and changes in transport policy and lifestyles.

During the Second World War, the companies' managements joined together, effectively operating as one company. Assisting the country's 'war effort' put a severe strain on the railways' resources and a substantial maintenance backlog developed. After 1945, for both practical and ideological reasons, the government decided to bring the rail service into the public sector.

1948 – 1994: British Rail

.jpg.webp)

From the start of 1948, the railways were nationalised to form British Railways (latterly "British Rail") under the control of the British Transport Commission.[18] Though there were few initial changes to the service, usage increased and the network became profitable. Regeneration of track and stations was completed by 1954. Rail revenue fell and, in 1955, the network again ceased to be profitable. The mid-1950s saw the hasty introduction of diesel and electric rolling stock to replace steam in a modernisation plan costing many millions of pounds but the expected transfer back from road to rail did not occur and losses began to mount.[19] This failure to make the railways more profitable through investment led governments of all political persuasions to restrict rail investment to a drip feed and seek economies through cutbacks.

The desire for profitability led to a major reduction in the network during the mid-1960s. Dr. Richard Beeching was given the task by the government of re-organising the railways ("the Beeching Axe").[20][21] This policy resulted in many branch lines and secondary routes being closed because they were deemed uneconomic. The closure of stations serving rural communities removed much feeder traffic from main line passenger services. The closure of many freight depots that had been used by larger industries such as coal and iron led to much freight transferring to road haulage. The closures were extremely unpopular with the general public at that time and remain so today.[22]

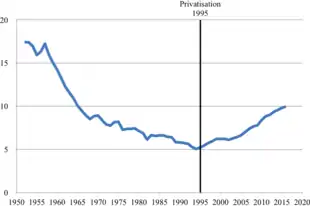

Passenger levels decreased steadily from the late fifties to late seventies.[23] Passenger services then experienced a renaissance with the introduction of the high-speed InterCity 125 trains in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[24] The 1980s saw severe cuts in government funding and above-inflation increases in fares, but the service became more cost-effective. Following sectorisation of British Rail, InterCity became profitable. InterCity became one of Britain's top 150 companies operating city centre to city centre travel across the nation from Aberdeen and Inverness in the north to Poole and Penzance in the south.[25]

Between 1994 and 1997, British Rail was privatised.[26] Ownership of the track and infrastructure passed to Railtrack, passenger operations were franchised to individual private sector operators (originally there were 25 franchises) and the freight services sold outright (six companies were set up, but five of these were sold to the same buyer).[27] The Conservative government under John Major said that privatisation would see an improvement in passenger services. Passenger levels have since increased strongly.[28]

1995 onwards: Post-privatisation

Since privatisation, numbers of passengers have grown rapidly; by 2010 the railways were carrying more passengers than at any time since the 1920s.[30] and by 2014 passenger numbers had expanded to their highest level ever, more than doubling in the 20 years since privatisation. Train fares cost more than under British Rail.[31]

The railways have become significantly safer since privatisation and are now the safest in Europe.[32] However, the public image of rail travel was damaged by some prominent accidents shortly after privatisation. These included the Southall rail crash (where a train with its faulty Automatic Warning System disconnected passed a stop signal),[33] the Ladbroke Grove rail crash (also caused by a train passing a stop signal)[34][35] and the Hatfield accident (caused by a rail fragmenting due to the development of microscopic cracks).[36]

Following the Hatfield accident, the rail infrastructure company Railtrack imposed over 1,200 emergency speed restrictions across its network and instigated an extremely costly nationwide track replacement programme. The consequential severe operational disruption to the national network and the company's spiralling costs set in motion the series of events which resulted in the ultimate collapse of the company and its replacement with Network Rail, a state-owned, not-for-dividend company.[37]

Since April 2016, the British railway network has been severely disrupted on many occasions by wide-reaching rail strikes, affecting rail franchises across the country.[38] The industrial action began on Southern services as a dispute over the planned introduction of driver-only operation,[39] and has since expanded to cover many different issues affecting the rail industry;[40] as of February 2018, the majority of the industrial action remains unresolved, with further strikes planned.[41] The scale, impact and bitterness of the nationwide rail strikes have been compared to the 1984–85 miners' strike by the media.

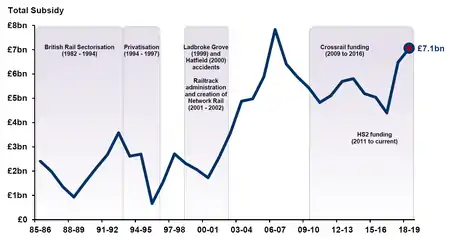

As of 2018, government subsidies to the rail industry in real terms were roughly three times that of the late 1980s.[42]

See also

- Economic history of the United Kingdom

- History of rail transport

- Rail transport in Great Britain

- List of early British railway companies

- History of rail transport in Ireland

- British postal system

- List of railway lines in Great Britain

- List of closed railway lines in Great Britain

- British narrow gauge railways

- British industrial narrow gauge railways

- Railway electrification in Great Britain

- British electric multiple units

- British railcars and diesel multiple units

- History by era

References

- Warren Allison, Samuel Murphy and Richard Smith, An Early Railway in the German Mines of Caldbeck in G. Boyes (ed.), Early Railways 4: Papers from the 4th International Early Railways Conference 2008 (Six Martlets, Sudbury, 2010), pp. 52–69.

- Jones, Mark (2012). Lancashire Railways – The History of Steam. Newbury: Countryside Books. p. 5. ISBN 978 1 84674 298 9.

- Hylton, Stuart (2007). The Grand Experiment: the Birth of the Railway Age 1820-1845. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-3172-2.

- Hamilton Ellis (1968). The Pictorial Encyclopedia of Railways. The Hamlyn Publishing Group. p. 12.

- Bayliss, D.A. (1981). Retracing the First Public Railway. Living History Local Guide No 4.

- Dawson, Paul L. (15 November 2015). Secret Wakefield. Amberley Publishing Limited.

- Ambler, D.W. (1989). The History and Practice of Britain's Railways: A New Research Agenda. Ashgate.

- Trevithick, Francis (1872). Life of Richard Trevithick: With an Account of His Inventions, Volume 1. E. & F.N. Spon.

- Hamilton Ellis (1968). The Pictorial Encyclopaedia of Railways. The Hamlyn Publishing Group. p. 20.

- "Puffing Billy". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on 15 November 2006. Retrieved 24 November 2006.

- "History of the locomotives". Archived from the original on 5 December 2006. Retrieved 24 November 2006.

- 1840 Railway Regulation Act, originally published by HMSO; link is to The Railways Archive

- Hall, Stanley (28 September 1990). Railway Detectives: The 150-year Saga of the Railway Inspectorate. Shepperton: Ian Allan Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7110-1929-4.

- 1844 Railway Regulation Act, originally published by HMSO; link is to The Railways Archive

- Mitchell, Brian; Chambers, David; Crafts, Nicholas (August 2009). "How good was the profitability of British Railways, 1870–1912?" (PDF). University of Warwick. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Keddell, F (1890). The Nationalisation of Our Railway System: Its Justices and Advantages. London: The Modern Press.

- HM Government (1921). "Railways Act 1921". The Railways Archive. (originally published by HMSO). Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- Her Majesty's Government (1947). "Transport Act 1947". The Railways Archive. (originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- "British Railways Board history". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 14 October 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- British Transport Commission (1963). "The Reshaping of British Railways - Part 1: Report". The Railways Archive. (originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- British Transport Commission (1963). "The Reshaping of British Railways - Part 2: Maps". The Railways Archive. (originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- "Did Dr Beeching get it wrong with his railway cuts 50 years ago?".

- The UK Department for Transport Archived 17 October 2004 at the Wayback Machine (DfT), specifically Table 6.1 from Transport Statistics Great Britain 2006 Archived 8 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine (4MB PDF file)

- Marsden, Colin J. (1983). British Rail 1983 Motive Power: Combined Volume. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-1284-4.

- "The fall and rise of Britain's railways". Rail Staff News. 19 December 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Her Majesty's Government (1903). "Railways Act 1993". The Railways Archive. (originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). Retrieved 26 November 2006.

- "EWS Railway - Company History". Archived from the original on 12 December 2006. Retrieved 26 November 2006.

- The UK Office of Rail Regulation Archived 9 November 2008 at the UK Government Web Archive (ORR), specifically Section 1.2 from National Rail Trends 2006-2007 Q1 Archived 7 November 2008 at the UK Government Web Archive (PDF file)

- "Department for Transport Statistics: Passenger transport: by mode, annual from 1952".

- "Growth of 6.9% in 2010 takes demand for rail travel to new high levels". Association of Train Operating Companies. February 2011. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Swaine, Jon (1 December 2008). "Train fares cost 0.6% more than under British Rail". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Britain's railways now safest in Europe".

- Professor John Uff (QC FREng) (2000). "Investigation The Southall Rail Accident Inquiry Report". The Railways Archive. (Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- The Rt Hon Lord Cullen (PC) (2001). "The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry: Part 1 Report". The Railways Archive. (Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- The Rt Hon Lord Cullen (PC) (2001). "The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry: Part 2 Report". The Railways Archive. (Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- Railway Safety; Standards Board (2004). "Hatfield Report and Recommendations". The Railways Archive. (Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- "Network Rail - Our History". Network Rail website. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- "Strikes under way in train safety row". BBC News. 8 January 2018.

- "Southern rail strike causes disruption". BBC News. 26 April 2016.

- "Strikes under way in train safety row". BBC News. 8 January 2018.

- "RMT announces new strike on Southern rail". BBC News. 22 February 2018.

- Rahman, Grace (7 November 2018). "How much does the government subsidise the railways by?". Full Fact. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

Sources

General

- Simmons, Jack; Biddle, Gordon, eds. (1999). The Oxford Companion to British Railway History: From 1603 to the 1990s (2nd ed.).

- White, H. P. (1986). Forgotten Railways. Newton Abbot, Devon: David St. John Thomas. ISBN 978-0-946537-13-6.

- Westwood, John. Illustrated History of the Railroads. Brompton Books.

Pre-1830

- Hadfield, Charles.; Skempton, A. W. (January 1979). William Jessop, Engineer. Newton Abbot: M.& M.Baldwin. ISBN 978-0-7153-7603-4.

- Schofield, R.B. (October 2000). Benjamin Outram, 1764-1805: An Engineering Biography. Cardiff: Merton Priory Press. ISBN 978-1-898937-42-5.

- Ransom, P.J.G. (July 1989). The Victorian Railway and How It Evolved. London: William Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-434-98083-3.

- "The History of the Railway in Britain". Historic Herefordshire Online. Retrieved 24 November 2006.

- "The Old Times - History of the Locomotive". Archived from the original on 5 December 2006. Retrieved 24 November 2006.

- Dendy Marshall, C.F. (1929). "The Rainhill Locomotive Trials of 1829". Transactions of the Newcomen Society. 9.

- Dowd, Steven (May 1999). "The Liverpool & Manchester Railway". Journal of the International Bond & Share Society. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 24 November 2006.

- "The Broad Gauge Story". Journal of the Monmouthshire Railway Society. Summer 1985. Retrieved 24 November 2006.

1830–1922

- McKenna, Frank. "Victorian Railway Workers," History Workshop (spring 1975) #1 pp. 26–73. in JSTOR

- Ransom, P.J.G. (July 1989). The Victorian Railway and How It Evolved. London: William Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-434-98083-3.

- Science Museum (November 1972). The Pre-grouping Railways: Their Development and Individual Characters: Part 1. London: The Stationery Office Books. ISBN 978-0-11-290153-2.

- Christine Heap; John Van Riemsdijk (November 1980). The Pre-grouping Railways: Their Development and Individual Characters: Part 2. London: The Stationery Office Books. ISBN 978-0-11-290309-3.

- Christine Heap; John Van Riemsdijk (November 1985). The Pre-grouping Railways: Their Development and Individual Characters: Part 3. London: The Stationery Office Books. ISBN 978-0-11-290432-8.

- (No Author) (1980). British Railways Pre-Grouping Atlas and Gazetteer (5th ed.). Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0320-0.

1923–1947

- Tourret, R. (November 2003). GWR Engineering Work, 1928-1938. Tourret Publishing. ISBN 978-0-905878-08-9.

- O.S. Nock (1967). History of the Great Western Railway Volume Three 1923-48. Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0304-0.

- Nock, O.S. (1982). A History of the LMS. Vol. 1: The First Years, 1923-1930. George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-385087-9.

- Nock, O.S. (1982). A History of the LMS. Vol. 2: The Record Breaking 'Thirties, 1931-1939. George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-385093-0.

1948–1994

- Henshaw, David (1994). The Great Railway Conspiracy: The Fall and Rise of Britain's Railways Since the 1950s (2nd ed.). Hawes, North Yorkshire: Leading Edge Press. ISBN 978-0-948135-48-4.

- Gourvish, Terry (2002). British Rail: 1974-97: From Integration to Privatisation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926909-9.

- "British Railways Board history". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 14 October 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2006.