Streamliner

A streamliner is a vehicle incorporating streamlining in a shape providing reduced air resistance. The term is applied to high-speed railway trainsets of the 1930s to 1950s, and to their successor "bullet trains". Less commonly, the term is applied to fully faired recumbent bicycles. As part of the Streamline Moderne trend, the term was applied to passenger cars, trucks, and other types of light-, medium-, or heavy-duty vehicles, but now vehicle streamlining is so prevalent that it is not an outstanding characteristic. In land speed racing, it is a term applied to the long, slender, custom built, high-speed vehicles with enclosed wheels.

Trains

Europe

The first high-speed streamliner in Germany was the "Schienenzeppelin", an experimental propeller driven single car, built 1930. On 21 June 1931, it set a speed record of 230.2 km/h (143.0 mph) on a run between Berlin and Hamburg. In 1932 the propeller was removed and a hydraulic system installed. The Schienenzeppelin made 180 km/h (112 mph) in 1933.

The Schienenzeppelin led to the construction of the diesel-electric DRG Class SVT 877 "Flying Hamburger". This two-car train set had 98 seats and a top speed of 160 km/h (99 mph). During regular service with the Deutsche Reichsbahn, starting on 15 May 1933, this train ran the 286 kilometres (178 mi) between Hamburg and Berlin in 138 minutes with an average speed of 124.4 km/h (77.3 mph). The SVT 877 was the prototype for the DRG Class SVT 137, first built in 1935 for use in the FDt express train service. During test drives, the SVT 137 "Bauart Leipzig" set a world speed record of 205 km/h (127 mph) in 1936. The fastest regular service with SVT 137 was between Hannover and Hamm with an average speed of 132.2 km/h (82.1 mph). This service lasted until 22 August 1939.

In 1935 Henschel & Son, a major manufacturer of steam locomotives, introduced the 4-6-4 DRG Class 05 high speed streamliner locomotives for use on the Deutsche Reichsbahn Frankfurt am Main to Berlin route.[1] Three examples were built during 1935–36. Built for top speeds of over 85 mph (137 km/h), they soon proved much faster in test runs. The DRG 05-002 made seven runs during 1935-36 during which it attained top speeds of more than 177 km/h (110 mph) with trains up to 254 t (250 long tons; 280 short tons) weight. On 11 May 1936 it set the world speed record for steam locomotives after reaching 200.4 km/h (124.5 mph) on the Berlin–Hamburg line hauling a 197 t (194 long tons; 217 short tons) train. The engine power was more than 2,535 kW (3,399 ihp)). That record was broken two years later by the British LNER Class A4 4468 Mallard engine. On 30 May 1936 the 05-002 set an unbroken start stop speed record for steam locomotives: During the return run from a 190 km/h test on the Berlin-Hamburg route it did the ~113 kilometres (70 miles) from Wittenberg to a signal stop before Berlin-Spandau in 48 min 32 s, meaning 139.4 km/h (86.6 mph) average between start and stop.

In the United Kingdom, development of streamlined passenger services began in 1934, with the Great Western Railway introducing relatively low-speed streamlined railcars, and the London and North Eastern Railway introducing the "Silver Jubilee" service using streamlined A4 class steam locomotives and full length trains rather than railcars. In 1938 on a test run, the locomotive Mallard built for this service set the official record for the highest top speed attained by a steam locomotive, reaching 126 mph (203 km/h). That record stands to this day. The London Midland and Scottish Railway introduced streamline locomotives of the Princess Coronation Class shortly before the outbreak of war.

The Ferrovie dello Stato (Italian railways) developed the FS Class ETR 200, a three-unit electric streamliner. The development started in 1934. These trains went into service in 1937. On 6 December 1937, an ETR 200 made a top speed of 201 km/h (125 mph) between Campoleone and Cisterna on the run Rome-Naples. In 1939 the ETR 212 even made 203 km/h (126 mph). The 219-kilometre (136 mi) journeys from Bologna to Milan were made in 77 minutes, meaning an average of 171 km/h (106 mph).

In the Netherlands, Nederlandse Spoorwegen (NS) introduced the Materieel 34 (DE3), a three unit 140 km/h (87 mph) streamlined diesel-electric trainset in 1934. An electric version, Materieel 36, went into service in 1936. From 1940 the "Dieselvijf" (DE5), a 160 km/h (99 mph) top speed five unit diesel-electric trainset based on DE3, completed the Dutch streamliner fleet. During test runs, a DE5 ran 175 km/h (109 mph). That year the similar electric Materieel 40 were first built. In the 1930s, NS also developed a streamlined version of the class 3700/3800 steam locomotive, nicknamed "potvis" (sperm whale).[2]

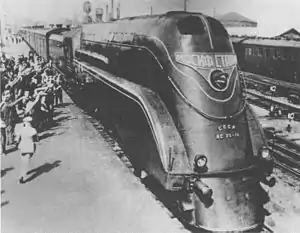

On the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the October Revolution, the Soviet Kolomna Locomotive Factory produced two examples of the wind-tunnel designed SŽD series 2-3-2К (4-6-4 Whyte Notation) streamliner locomotive for Moscow-Leningrad service. During testing, it was shown capable of speeds greater than 150 km/h (93 mph), and it entered service in 1938. Production of the series was canceled with the onset of World War II.

In Czechoslovakia in 1934, Czechoslovak State Railways ordered two motor railcars with maximum speed 130 km/h (81 mph). The order was received by Tatra company, which was producing first streamlined mass-produced automobile Tatra 77 in that time. The railcar project was led by Tatra chief designer Hans Ledwinka and received streamlined design. Both ČSD Class M 290.0 were delivered in 1936 with desired 130 km/h (81 mph) maximum speed, although during test runs one car reached 148 km/h (92 mph) mark. They were run on Czechoslovak prominent route Prague-Bratislava under Slovenská strela (Slovak for "Slovak Arrow") brand.

During the 1930s, streamlined Luxtorpeda diesel units that Austrian and later Polish manufacturers constructed were reaching speeds of up to 140 km/h (87 mph) in Poland. During that period, the streamlined Pm36-1 steam locomotive pulled the Nord Express between Poland and Paris.

United States

The earliest known streamlined rail equipment in the United States were McKeen rail motorcars built for Union Pacific and Southern Pacific between 1905 and 1917. Most of them sported a pointed "wind splitter" front, a rounded rear, and round porthole style windows in a style that was as much nautically as aerodynamically inspired. The McKeen cars were unsuccessful because internal combustion drive technology for that application was completely unreliable at the time and the lightweight frames dictated by their limited power tended to break. Streamlined rail motorcars would appear again in the early 1930s after the internal combustion-electric propulsion technology developed by General Electric and promoted by the Electro-Motive Company became the accepted technology for rail motorcars in the 1920s.

Streetcar builders sought to build electric cars with improved speed for interurban lines through the 1920s. In 1931 the car builder J.G. Brill introduced the Bullet, a lightweight, wind-tunnel designed car with a pointed front that could run either singly or in multiple-unit sets, capable of speeds over 90 miles per hour. Depression-era economics cut into their sales but the design was highly successful in service, lasting into the 1980s.

The Pullman Company first experimented with lightweight self-propelled railcars in co-operation with the Ford Motor Company, concurrent with Ford's development of their Trimotor aircraft, in 1925. In 1931 they enlisted the services of the Trimotor design contributor William Bushnell Stout to apply airplane fuselage design concepts to railcars. The result was the Railplane (not the Bennie Railplane), a streamlined self-propelled railcar with a tapered cross-section, lightweight tubular aluminum space frame and duralumin skin. During testing with the Gulf, Mobile and Northern Railroad in 1932, it reportedly reached 90 miles per hour. Union Pacific had been seeking improvements to self-propelled railcars based on European design ideas and the performance of the Railplane encouraged them to redouble their efforts in partnership with Pullman-Standard.[3]

In 1931 the Budd Company reached an agreement with the French tire company Michelin to produce pneumatic-tired rail motorcars in the US, as an improvement on the heavy, underpowered, and shimmy-prone "doodlebugs" that ran on American tracks. In that endeavor, Budd would produce lightweight rail equipment utilizing unibody construction and the high strength alloy stainless steel, enabled by shot welding, a breakthrough in electrical welding technique. The venture produced articulated power-trailer car sets with streamlined styling, which left the Budd Company just a (much) more powerful engine away from producing a history-making streamlined trainset.

The Great Depression caused catastrophic loss of business for the rail industry as a whole and for manufacturers of motorized railcars whose primary markets, branch line services, were among the first to be cut. The interests of lightweight equipment manufacturers and rail operators converged in the development of a new generation of lightweight, high speed, internal combustion-electric powered streamlined trainsets for mainline service.[3] The Burlington and Union Pacific railroads sought to increase the efficiency of their passenger service and looked to the lightweight, petroleum-powered technology offered by Budd and Pullman-Standard for their solutions. Union Pacific's project was named the M-10000 (named The Streamliner and later City of Salina in revenue service 1935–41) and Burlington's was named the Burlington Zephyr. Both were articulated designs and went into service as three-car (including power car) sets. The prime mover for the Zephyr's propulsion was a new 600 hp diesel engine and for the M-10000 a 600 hp spark-ignition engine running on "petroleum distillate", a fuel similar to kerosene. Both engines were produced by Winton Engine Corporation, a subsidiary of General Motors.

Both trainsets were star attractions at the 1934 World's Fair ("A Century of Progress") in Chicago, Illinois. The M-10000 was officially named The Streamliner during its demonstration period, the original use of the term with respect to trains. Its publicity tour from February to May 1934 attracted over a million visitors and attention in national media as the herald of a new era in rail transportation. On 26 May 1934, the Zephyr made a record-breaking "Dawn to Dusk" run from Denver, Colorado to Chicago for its grand entry as a Century of Progress exhibit. The Zephyr covered the distance in 13 hours, reaching a top speed of 112.5 mph (181.1 km/h) and running an average speed of 77.6 mph (124.9 km/h). The fuel for the run cost US$14.64 (at 4¢ per U.S. gallon). The event was covered live on radio and drew large, cheering crowds as the "silver streak" zipped by. Adding to the sensation of the Zephyr were the striking appearance of its fluted stainless steel bodywork, and its raked, rounded, aerodynamic front end that symbolized its modernity and would echo in steam locomotive styling in the following years.

The Zephyr, after its Worlds Fair display and a nationwide demonstration tour, entered revenue service between Kansas City Missouri and Lincoln Nebraska on 11 November 1934. A total of nine Zephyr trainsets were built for Burlington between 1934 and 1939, serving various midwestern routes as named trains. The Burlington Zephyr was renamed the Pioneer Zephyr in honor of its status as the first of the fleet. Two Twin Cities Zephyrs of the same three-car configuration entered service on the link between Chicago and the Twin Cities in April 1935. Larger trainsets were built and put into service over longer routes, using Winton's more powerful engines, twin-engine power units, and eventually booster power units to meet the additional power requirements. The four-car Mark Twain Zephyr went into service on the Saint Louis Missouri – Burlington Iowa run in October 1935. Two partially-articulated six-car sets entered Denver Zephyr service between Chicago and Denver in May 1936. They were replaced by a pair of partially-articulated ten-car sets in November 1936, in turn replacing the original Twin Cities Zephyr sets which then went to other routes run by Burlington. The last of the classic Zephyrs built was for the Kansas City – Saint Louis General Pershing Zephyr run, entering service in June 1939 with GM's newest 1000 hp engine and conventional coupling. The original Zephyr trainsets remained in service well into the postwar era, with the last six-car set retiring as the Nebraska Zephyr in 1968.

M-10000 went into service between Kansas City, MO and Salina, KS, on 31 January 1935, as The Streamliner, later becoming the City of Salina under Union Pacific's naming convention for its expanding fleet of diesel-powered streamlined trainsets. The M-10000 served that route as a three-car set until it was retired in 1941 then scrapped in 1942; it provided Duralumin recycled for military aircraft.[4]

Union Pacific commissioned five more trainsets evolved from the initial M-10000 design and inaugurated high-speed service out of Chicago with its City of Portland (June 1935), Los Angeles (May 1936), San Francisco (June 1936), and Denver (June 1936) streamliners. The M-10001 set consisted of a single power unit with a 1200 hp Winton diesel engine pulling six tapered low profile cars in the form of the original M-10000 set. The M-10002 set consisted of a 1200+900 hp cab/booster locomotive pulling nine cars of the same form. The San Francisco and Denver sets were powered by automotive-styled cab/booster locomotive sets with 1200 hp engines. The two City of Denver sets started service two cars shorter than the M-10002 and M-10004 sets, with roomier and heavier straight-sided cars. Initial service to the west coast consisted of five runs monthly for each route. Daily overnight service was maintained on the Chicago – Denver run by assigning three locomotive sets for two trains, then augmenting that stable with locomotive equipment pulled from other runs.

Despite the breakthrough schedule times of the long-distance M-1000x "City" trains the service record of the fleet reflected the limitations of their technology in meeting the demands of long-distance and higher capacity service. The M-10001 served for 32 months as City of Portland until it was replaced, re-entered service on the Portland – Seattle run, then was pulled from service for the last time in June 1939. The M-10002 spent 19 months as City of Los Angeles, 39 months as City of Portland, ten months out of service starting in July 1941, then was retired for good in March 1943 after serving on the Portland – Seattle run. After 18 months of service as City of San Francisco M-10004 spent six months being refurbished, then served as a second unit on the Los Angeles run from July 1938 until it was pulled from service in March 1939. The M-10001 and M-10004 power units were converted to additional boosters for the City of Denver trains and their car sets became spare equipment. The two City of Denver trainsets, after cannibalizing power from M-10001 and M-10004, stayed in service until 1953.

The GG1 electric locomotives brought streamlined styling to the Pennsylvania Railroad's fleet of electric locomotives in late 1934.

Boston and Maine's Flying Yankee, identical to the original Zephyr, entered service between Boston and Portland Maine on 1 April 1935.

The Gulf, Mobile and Northern Railroad Rebel trainsets were similar to the Zephyr in form, but not articulated. Designed by Otto Kuhler, the ALCO powered diesel-electrics built by American Car and Foundry Company were placed into service on 10 July 1935.

The Illinois Central 121 trainset was the first of the Green Diamond streamliners running between Chicago and St Louis. It was a five-unit (including power car) articulated trainset for day service. The Pullman-built set had the same power format and 1200 hp Winton diesel engine as M-10001, with some style aspects that resembled the later M1000x trainsets. It ran from May 1936 until it was replaced in 1947. After an overhaul it was placed on the Jackson Mississippi – New Orleans run until it was retired and scrapped in 1950.

The visual styling of the new trainsets made the existing fleets of locomotives and railcars suddenly look old hat. Rail lines soon responded by adding streamlined shrouding and varying degrees of mechanical improvement to older locomotives, and re-styling heavyweight cars. The first American steam locomotive to receive that treatment was one of the New York Central Railroad's J-1 Hudson class locomotives built in 1930, which was re-introduced with streamlined shrouding and named the Commodore Vanderbilt in December 1934.[5] The Vanderbilt styling was a one-off design by Carl Kantola. NYC's next venture in streamline styling was the full-length exterior and interior design of their Mercury trainsets by Henry Dreyfuss in 1936. Raymond Loewy designed art-deco shrouding with a bullet-front scheme for Pennsylvania Railroad's K4s locomotives in 1936. In 1937, variations of the bullet-front design were used by Otto Kuehler on a 4-6-2 locomotive for B&O's Royal Blue, and Dreyfuss on NYC's new J-3a Hudsons for the Twentieth Century Limited and other express trains.

While streamlining on steam locomotives was more about marketing than performance, newly designed locomotives with state-of-the-art steam technology became very fast. The Milwaukee Road class A Atlantics, purpose-built to compete with the Twin Cities Zephyr in 1935, were the first "steamliners" equipped to back up their styled claim to extra speed. During a run by locomotive #2 with a dynamometer car on May 15, 1935, a top speed of 112.5 mph (181.1 km/h) was recorded. This was the fastest authenticated speed reached by a steam locomotive at the time, making #2 the rail speed record holder for steam and the first steam locomotive to top 110 mph (180 km/h). That record lasted until a German DRG Class 05 locomotive exceeded it the following year. In 1937 Milwaukee introduced the class F7 Hudsons on the Twin Cities Hiawatha run, which were known to cruise above 110 mph (177 km/h) and said to exceed 120 mph (193 km/h) on occasion.[6] The Milwaukee Road's speedsters were designed by Otto Kuehler with "shovel nose" styling and for the Class A some details evocative of the Zephyrs.

Streamliner steam locomotives continued to be produced into the early postwar era; among the most distinctive were Pennsylvania Railroad's duplex-drive 6-4-4-6 type S1 and 4-4-4-4 type T1 locomotives styled by Raymond Loewy. In terms of service longevity, the most successful were the Southern Pacific GS-3 locomotives introduced in 1938 and the Norfolk and Western J1 class locomotives introduced in 1941. In contrast to designs that completely encased the boiler in shrouding, streamlining of the GS-3/GS-4 series locomotives consisted of skyline casing flush with the smokestack and smoke-lifting skirting along the boiler that left the silver-painted smokebox on full display.

The GM Electro-Motive Corporation (EMC) started production of streamlined diesel passenger locomotives, incorporating the lightweight carbody construction and raked, rounded front end introduced with the Zephyr and the high-mounted, behind-the-nose cab of the M-1000x locomotives, in 1937. The TA was a 1200-hp version produced for the Rock Island Rockets, a series of six lightweight, semi-articulated three and four-car trainsets. The EMC E series locomotives incorporated two features of their earlier EMC 1800 hp B-B development design locomotives, the twin-engine format and multiple-unit control systems that facilitated cab/booster locomotive sets. The E-units brought sufficient power for full-sized trains such as the B&O Capitol Limited, AT&SF Super Chief, and Union Pacific's upgraded City of Los Angeles and City of San Francisco, which challenged steam power in all aspects of passenger service. EMC introduced standardized production to the locomotive industry, with its attendant economies of scale and simplified processes for ordering, producing, and servicing locomotives, and offered a variety of support services lowering the technological and initial cost barriers that could deter conversion to diesel.

With power and reliability of new diesel units improved with the 2000 hp GM 567 powered E3 model in 1938, the advantages of diesel became compelling enough for a growing number of rail lines to select diesel over steam for new passenger equipment. The power and top speed advantages of state-of-the-art steam locomotives were more than offset by diesel's advantages in service flexibility, downtime, maintenance costs, and economic efficiency for most operators. The American Locomotive Company (ALCO), the builder of the Hiawatha speedsters, saw diesel as the future of passenger service and introduced streamlined locomotives influenced by the design of the E units in 1939. The replacement of steam with diesel power was interrupted by the US entry into World War II, with a military premium on diesel technology that stopped all production of diesel locomotives for passenger service between September 1942 and January 1945.

Japan

The trend of streamliners also hit Japan. In 1934, the Ministry of Railways (Japanese Government Railways, JGR) decided to convert one of its 3-cylinder steam locomotives class C53 into a streamlined style. The selected locomotive was No.43 of class C53. However Hideo Shima, the chief engineer of the conversion, thought streamlining had no practical effect on reducing air resistance, because Japanese trains at that time did not exceed the maximum speed of 100 km/h (62 mph). Therefore, he designed the locomotive to create airflow that lifted exhaust smoke away from the locomotive. He had expected no practical effect on reducing air resistance completely, therefore he never tried to test fuel consumption or tractive force of the converted locomotive.[7] The Japanese government planned to use this one converted streamline locomotive on the passenger express route between Osaka and Nagoya.[8]

The converted locomotive gained much popularity from the public. So JGR decided to build 21 new streamlined versions of the class C55 locomotive(Japanese). Additionally, JGR built 3 streamlined class EF55 electric locomotives. Kiha-43000 diesel multiple units and Moha-52 electric multiple units also received a streamlined style. South Manchuria Railway under Japanese control at that time also designed the Pashina class streamlined locomotives, and operated the Asia Express which had total coordinated style with Pashina locomotives.[7]

These streamlined steam locomotives took many man-hours to repair due to their casing. After the outbreak of WW2, the lack of an experienced labor force made the problems worse. Finally, the casings were removed and these locomotives were used with a miserable appearance.[7]

Australia around World War II

Streamliner locomotives arrived relatively late in Australia. In 1937 streamlined casings were fitted on four Victorian Railways S class locomotives for the Spirit of Progress service between Melbourne and Albury. Similar casings were then fitted on two Tasmanian Government Railways R class narrow-gauge locomotives for the Hobart to Launceston expresses.

Despite — or perhaps because of — the strategic priorities of World War II, some new streamliner locomotives were built in Australia during and immediately after the war. The first five New South Wales C38 class locomotives were modestly streamlined with distinctive conical noses, while the twelve South Australian Railways 520 class locomotives featured extravagant streamlining in the style of the Pennsylvania Railroad's T1.

In all cases, the streamlining on Australian steam locomotives were purely aesthetic, with negligible impacts on train speeds.

United States

High-speed steam service continued after the war ended, but became increasingly uneconomic. New York Central's Super Hudsons went out of service in 1948 as the line converted to diesel for passenger service. The Milwaukee Road retired its high speed Hiawatha steam locomotives between 1949 and 1951. All of those iconic locomotives were scrapped. The last of Pennsylvania Railroad's short-lived T1 class locomotives went out of service in 1952. The last steam streamliners built were three Norfolk and Western 4-8-4 J1 class locomotives in 1950. They were in revenue service until 1959.

In 1951 the Interstate Commerce Commission implemented regulations restricting most trains to speeds of 79 mph (127 km/h) or below unless automatic train stop, automatic train control, or cab signalling were installed.[9] The new regulations minimized one of the key advantages of rail travel over the automobile, which became an increasingly attractive alternative as postwar construction of highway systems progressed. Rail operators marketed their services on the basis of luxurious sightseeing as airlines increasingly competed with rail lines for long-distance travel.

In 1956 General Motors and a Baldwin-Pullman consortium experimentally revived the lightweight custom streamliner concept. Neither project achieved any lasting impact on passenger service. GM's project was Aerotrain, featuring a futuristic automotive-styled cab unit pulling cars adapted from GM's long-distance bus coach design.[10][11] The Dan'l Webster and Xplorer streamliners, featuring a low profile and aluminum cars, served in the New York-New Haven area and in Ohio, respectively, but were problematic and soon withdrawn from service.

The advent of jet air travel in the late 1950s brought forth a new round of price competition from airlines for long-distance travel, severely affecting the ridership and profitability of long-distance passenger rail service. Government regulations forced railroads to continue to operate passenger rail service, even on long routes where, the railroads argued, it was almost impossible to make a profit. Unlike air and automotive infrastructure, which were government subsidized, rail infrastructure was entirely supported by operating revenues. By the late 1960s, most operators were seeking to get out of passenger service altogether.

Since 1971, Amtrak has operated the majority of passenger rail systems in the United States. The last E units in regular service were retired in 1993. Some GG1 electric locomotives remained in service until 1983. The lightweight, aerodynamic carbody construction pioneered with the Zephyr has been reintroduced with Amtrak's GE Genesis diesel locomotives in their quest for greater fuel efficiency.

Amtrak's Acela Express trains traveling at speeds of up to 150 mph (240 km/h) have been introduced in the Boston to Washington, D.C. Northeast Corridor.[12] Many areas around the United States have been considering construction of new high-speed lines, but rail travel is much less common in the United States than in Europe or Japan. In 2008, California voters approved bonds to initiate construction of high-speed rail lines serving the Central Valley, the Bay Area, and southern California. Construction of the first segment, between Bakersfield and Merced, began in 2015. Higher than anticipated administrative and construction costs led to the suspension of further construction in 2019.

Preserved examples

After 26 years of service and traveling over 3,000,000 miles (4,800,000 km), the Pioneer Zephyr went to Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry. The Flying Yankee, the third streamliner to enter service, is undergoing restoration to operational condition. The Silver Charger locomotive of the General Pershing Zephyr trainset remained in service until 1966 and is also undergoing restoration.

In December 1974, the streamlined steam-powered Southern Pacific 4449 "Daylight" came off an outdoor public dispay to undergo a restoration and re-painting that enabled it pull the American Freedom Train, which toured the 48 contiguous United States as part of the nation's 1976 Bicentennial celebration.[13] With the exception of occasional interruptions for maintenance and inspections, the restored locomotive has operated in excursion service throughout that area since 1984.[14]

The twice-restored streamlined Norfolk and Western Railway's steam-powered J1 locomotive Number 611 operated in excursion service within the United States from 1982 to 1994 and from 2015 to 2017.[15] The locomotive has traveled for display at special events.[16]

Examples of the pre-World War II "slant nose" EMC EA, E3, E5, and E6 locomotives are on display at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Museum, the North Carolina Transportation Museum, the Illinois Railway Museum, and the Kentucky Railway Museum. The stainless steel clad E5 is occasionally matched with one of the original Denver Zephyr car sets for excursion service. As of 2017, the Rock Island No.630 E6 unit was under restoration for display in Iowa.

Two EMD LWT12 locomotives and several passenger cars of two General Motors Aerotrains are presently on display within the United States. The National Railroad Museum in Green Bay, Wisconsin now exhibits the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad's Aerotrain locomotive No. 2 and two passenger cars.[10][17] The Museum of Transportation in Kirkwood, Missouri (near St. Louis) exhibits the Rock Island's locomotive No. 3 and two passenger cars.[10][18]

Europe

In Europe, the streamliner tradition gained new life after World War II. In Germany, the DRG Class SVT 137 were used again, but at a slower speed. Based on the Kruckenberg SVT 137 the DB Class VT 11.5 (later renamed to DB Class 601) was used as "Trans Europ Express (TEE)" for international high-speed trains.

In East Germany, the DR Class VT 18.16 was built for international express service also. From 1965, DB used more and more streamlined electric locomotives DB Class 103 with regular trains for high-speed service, but from 1973 DB used with the DB Class ET 403 (nickname "Donald Duck") a real streamliner again. The ET 403 was a four-unit electric train with tilting technology.

Since 1991 the ICE Service with ICE 1 (Class 401) is used for high-speed service. However, it needed 60 years to break the record speed of the first "Flying Hamburger" from 1933 on the run Hamburg-Berlin.

The Swiss SBB and the Dutch NS developed the RAm TEE (Dutch: DE) for the routes Zurich-Amsterdam and Amsterdam-Brussels-Paris. These trains were sold in 1977 to the Canadian Ontario Northland Railway (ONR) and served on the line Toronto–Moosonee as the Northlander. From 1961, SBB used the SBB RAe TEE II, a four system electric streamlined trainset for the TEE service.

Italy used pre-war trains and FS developed new trains such as the FS Class ETR 300 ("Settebello", FS Class ETR 401, ETR 450 (Pendolino) and ETR 500.

In the United Kingdom streamline services ended with the outbreak of WWII. During the war, the LNER and LMS streamlined locomotives had part of their streamlining removed to aid maintenance. By the late 1940s and early 1950s, the state of the railways was improving as track conditions caused by war damage and delayed maintenance work were repaired for more mainline track for high speed running.

The first experiments with diesel streamliner services in the United Kingdom were the Blue Pullman trains introduced in 1960 and withdrawn in 1973. These provided 90 mph (140 km/h) luxury business services, but were marginally successful and ran a little faster than mainstream services. The Blue Pullman was followed by research into streamlined trains and tilting trains which led to the iconic InterCity 125 (Class 43) offering 125 mph (201 km/h) train services across the United Kingdom.

Japan

After WW2, Japanese railroads favored multiple unit type trains, even on its mainlines. In 1949, Japanese National Railways (JNR) released Series 80 EMUs which were used for long-distance trains for the first time as multiple unit trains. The lead coaches of Series 80 EMUs built after 1950 incorporated a streamlined design.

In 1957, Odakyu Electric Railway released 3000 series EMUs. The exterior design was developed using a wind tunnel intended for aircraft. Odakyu 3000 marked the world speed record at the time (145 km/h (90 mph)) for a narrow-gauge train. Multiple Unit trains were now proven suitable for long-distance trains by the JNR Series 80 and for high-speed trains by the Odakyu 3000.

These experiences led to the development of the first Shinkansen, the 0 Series. 0 series were strongly influenced by the Odakyu 3000, and also developed using a wind tunnel. The lead coaches of the 0 series were developed using a Douglas DC-8 for a reference. At a speed of 200 km/h (120 mph), the aerodynamic style of the 0 series "bullet train" had a substantial effect on reducing air resistance.[19][20]

High speed train services today

Worldwide many, if not most, high speed passenger trains are now streamlined, and speeds continue to rise as high-speed rail services become the normal long-distance rail service.

Specific trainsets

Streetcars and high-speed interurbans

Early versions of the PCC streetcars were referred to as Streamliners' in North America.

However, aerodynamic research appeared much earlier on the interurban scene, i.e. among the forerunners of the recent light rail. In 1905, the Electric Railway Test Commission started a series of test runs to develop a carbody design that would reduce wind resistance at high speeds. Vestibule sections of different shapes were suspended independent of the carbody, with a dynamometer to measure the resistance of each. Over 200 test runs were made at speeds up to 70 mph (c. 112 km/h) with parabolic, wedge, standard, and flat vestibule ends.

The test results indicated that a parabolic-shaped front end reduced wind resistance at high speeds below that of the conventional rounded profile. However, with that time's heavy railcars and moderate speeds, no significant operating economies were realized. Streamlining was discarded for another quarter-century.[21]

From the 1920s, however, stronger alloys, lightweight metals, and better design were all used to reduce carbody weight – which in turn permitted the use of smaller bogies and motors with corresponding economies in power consumption. In 1922, the G. C. Kuhlman Car Company built ten lightweight cars for the Western Ohio Railway.[22]

After an elaborate wind tunnel investigation – the first in the railway industry[23] – J. G. Brill Company in 1931 made their first Bullet railcars, capable to speeds above 90 mph (145 km/h).[24] With 52 seats, they weighed only 26 tons though some of them were almost 60 years in use.

Automobiles

Many engineers tried to incorporate aerodynamics into the shape of cars in the 1920s, and some entered production. The first such automobile (a prototype) to have a tear-drop shape and have the wheels within the body was the Persu automobile[25] (1922), with a drag coefficient of 0.22, built by Romanian engineer Aurel Persu.

Production vehicles

- Chrysler Airflow [26]

- Hudson Commodore [27][28]

- IHC Metro [29]

- Lincoln-Zephyr [30][31]

- Pontiac Streamliner [32]

- Saab 92 [33]

- Tatra T77

- Toyota AA

- VW Beetle

- Citroen DS [33]

Electric

Internal combustion

Jet and rocket

Experimental vehicles

- Dymaxion (1933)

- Schlörwagen (1939)

Bicycles

Bicycle fairings help to streamline the vehicle and rider. Velomobiles, completely enclosed bicycles or tricycles, take streamlining even further. It is streamliner bicycles that have set many HPV land records.[34]

Buses

Many buses adopted a stylish streamline look in the 1930s[35] with tests showing that streamlined design reduced fuel costs.[36]

Starting in 1934, Greyhound Lines worked with the Yellow Coach Manufacturing Company for its Series 700 buses, first for Series 719 prototypes in 1934, and from 1937 as the exclusive customer for Yellow's Series 743 bus, which Greyhound named the "Super Coach" and bought a total of 1,256 between 1937 and 1939.[37]

General Motors also custom-built twelve streamlined Futurliners for its 1936 Parade of Progress and, later the 1939 New York World's Fair and travelling exhibits.[38]

Motorcycles

Land-speed record

Motorcycle land-speed record-breaking streamliners include:

- Ack Attack

- Big Red

- BUB Seven Streamliner

- Gyronaut X-1

- Lightning Bolt

- NSU Delphin I and Delphin III

- Silver Bird

Highway efficiency

Ships

Streamlining was applied to the art deco style auto/passenger ferry Kalakala in the 1930s. The Kalakala operated until 1967 and was scrapped early in 2015.

Trailers

Camping (caravan) trailer manufacturers used streamlining to make trailers easier to tow. Current and past manufactures include Airstream, Avalon, Avion, Boles Aero, Bonair Oxygen, Curtis Wright, Silver Streak, Spartan, Streamline, and Vagabond.

Sterling Streamliner diners

Inspired by the streamlined trains, and especially the Burlington Zephyr, Roland Stickney designed a diner in the shape of a streamlined train called the Sterling Streamliner in 1939.[39] Built by J.B. Judkins, a firm that also made custom car bodies,[40] the Sterling and other diner production ceased in 1942 at the beginning on American involvement in World War II.

Two Sterling Streamliners remain in operation: the Salem Diner at its original location in Salem, Massachusetts and the Modern Diner in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Another Sterling Streamliner lies abandoned on Hix Bridge Road in Westport, Massachusetts.

Notes

- "Locomotive with Streamline Shell is Designed for Speed". Popular Mechanics. 64 (4): 541. October 1935. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- "Nederlands: Stoomlocomotief nr. 3804 (serie 3700/3800) van de NS met stroomlijnbekleding (bijnaam 'Potvis'); circa 1936. Collectie van het Utrechts Archief". Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Solomon, Brian (2015). Streamliners: Locomotives and Trains in the Age of Speed and Style. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0760347478.

- Strack, Don. "Union Pacific Diesel Story, 1934-1982". UtahRails.net.

- "Streamline Steam Engine Attains High Speed". Popular Mechanics. 63 (2): 122. February 1935. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Scribbins 1970, p. 63.

- Shima, Hideo; Takada, Takao; Yoshimura, Mitsuo (January 1984). "Three-way conversation on streamlined era". The Railway Pictorial (in Japanese) (426): 10–15.

- "Fast Express Train in Japan Hauled by Streamline Engine". Popular Mechanics. 65 (4): 551. April 1936. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- "Ask Trains from November 2008". Trains Magazine. 23 December 2008. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- (1) "GM's "Aerotrain": History And Operation". American-Rails.com. Retrieved 13 May 2020. Archived May 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

(2) Knight, Nick (4 May 2016). "When Streamliners died! Aerotrain failed to capture the imagination of the American public". The Vintage News. Retrieved 9 May 2020. - (1) "The 'Aerotrain': GM's Most Modern Train". Archived from the original on 28 July 2005. Retrieved 16 October 2020. In "Automotive Hollywood: The Battle for Body Beautiful". Archived from the original on 27 July 2005. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

(2) GUSTAVTIME (6 December 2018). "High Speed Aerotrain!" (video). Retrieved 18 May 2020 – via YouTube. 10:39 minutes video showing internal and external views of a demonstration Aerotrain traveling at speeds of up to 80 miles (129 km) per hour as Pennsylvania Railroad No. 1000 and external views of Aerotrain No. 1001 traveling on the Sacramento Northern Railway. - "Northeast Corridor Employee Timetable #5" (PDF). National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak). 7 June 2020. p. 110. Retrieved 24 December 2017 – via National Transportation Safety Board. Archived 7 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- (1) "Excursions: American Freedom Train". Friends of 4449. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

(2) Wines, Larry (2019). "The Story of the 1975 - 1976 American Freedom Train". Freedomtrain.org. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

(3) Barris, Wes. "The American Freedom Train". Steamlocomotive.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

(4) "The Second Coming Of The Freedom Train". The American Freedom Trains Come To Pittsburgh: September 15–17, 1948 and July 7–10, 1976. The Brookline Connection. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

(5) Kelly, John (25 May 2019). "In 1975 and '76, an artifact-filled choo-choo chugged around the U.S." The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019. - (1) Huxtable, Nils (2002). Daylight Reflections, Vol. 1: From Daylight to Starlight (1st ed.). Steamscenes. pp. 75, 95. ISBN 978-0969140924.

(2) "Excursions: Bend, March 23-24, 2002". Friends of SP 4449. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

(3) Franz, Justin (8 June 2015). "SP 4449 poised to steam in 2015". Trains Magazine News Wire. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

(4) "SP 4449 News and Recent Events". SP 4449. Portland, Oregon: Friends of SP 4449. 2019. Archived from the original on 7 November 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

(5) "Holiday Express 2019". Holiday Express Train. TicketsWest. 2019. Archived from the original on 3 November 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2019. - (1) Wrinn, Jim (2000). Steam's Camelot: Southern and Norfolk Southern Excursions in Color (1st ed.). TLC Publishing. pp. 102–105. ISBN 1-883089-56-5.

(2) "Upcoming Events". Roanoke, Virginia: Virginia Museum of Transportation. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

(3) "611 Spring Excursions". Spencer, North Carolina: North Carolina Transportation Museum. 11 January 2016. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

(4) "The Roanoker, Greensboro/Roanoke/Greensboro April 23 & 24". Roanoke, Virginia: Virginia Museum of Transportation. 2016. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

(5) "Excursion Tickets!". Roanoke, Virginia: Virginia Museum of Transportation. 2016. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2017. - (1) "611 Visits Strasburg – A Reunion of Steam". Ronks, Pennsylvania: Strasburg Rail Road. 2019. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

(2) Knight, Chris (22 August 2019). "Massive N&W; 611 train made its way to Strasburg Rail Road [photos]". LNP Media Group. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019. - (1) "The General Motors Aerotrain". Green Bay, Wisconsin: National Railroad Museum. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.. Note: Page contains a description of the Aerotrain and an image of the front of Aerotrain locomotive number 2.

(2) "Aerotrain No. 2". August 1970. Archived from the original (photograph) on 14 May 2020 – via Flickr.Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific RR ... "Aerotrain No. 2" at the National Railroad Museum, Green Bay, 8/70

.

Note: Photograph shows a train apparently consisting of Rock Island Aerotrain locomotive number 2, two Aerotrain coaches and additional non-Aerotrain coaches. - (1) "1955: Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific "Aerotrain" #3". St. Louis, Missouri: The National Museum of Transportation. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

(2) "The Aerotrain". Streamliner Memories. 28 February 2013. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020..

(3) "1955: Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific "Aerotrain" #3". St. Louis, Missouri: National Museum of Transportation. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2020..

(4) "Living St. Louis - Aerotrain" (video). St. Louis, Missouri: KETC. Retrieved 25 May 2020 – via YouTube.Producer Jim Kirchherr visits the Museum of Transportation where the GM Aerotrain is on display.

Video: 9:12 minutes.

(5) "Science Matters - Episode 126 - Aerotrain" (video). 1 October 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2020 – via YouTube.The Aerotrain on display at the Museum of Transportation did not live up to its billing as "the train of the future" despite its modern styling and engineering innovations.

Video: 8:06 minutes. - Yoshio Ubukata, "50 years of streamlined EMUs and DMUs in Japan" The Railway Pictorial No.426 (January 1984) pp.16 – 22 Denkisha Kenkyukai (in Japanese)

- Shinichi Tanaka, "Streamlined style of Shinkansen rolling stocks" The Railway Pictorial No.426 (January 1984) pp.29 – 31 Denkisha Kenkyukai (in Japanese)

- Middleton 1961, pp. 65–66

- Middleton 1961, pp. 62–63

- P & W High-Speed Line; http://www.phillytrolley.com/philwest.html

- Middleton 1961, pp. 69–70

- "Streamline power vehicle". European Patent Office.

- Billington, David P.; Billington, Jr., David P. (2013). Power, Speed, and Form: Engineers and the Making of the Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press. p. 199. ISBN 9781400849123. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Golfen, Bob (2 December 2018). "Handsome Hudson Commodore". Classic Cars Journal. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Dickson, Sam (11 March 2016). "The Spirit of Tomorrow: The Streamliners……". The Vintage News. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- McNessor, Mike (May 2016). "Metro Sensible – 1951 International Harvester Metro". Hemmings Classic Car. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Lincoln-Zephyr - the First Successful Streamlined Car in America". DriveTribe. 25 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "1936 Lincoln Zephyr Sedan". The Henry Ford. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

Even the tail lights are streamlined. The Zephyr was a streamlining success.

- Gunnell, John (2012). Standard Catalog of Pontiac, 1926-2002. Penguin. ISBN 9781440232404. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Lewin, Tony (2017). Speed Read Car Design: The History, Principles and Concepts Behind Modern Car Design. Motorbooks. p. 30. ISBN 9780760362068. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- International Human Powered Vehicle Association http://ihpva.org/land.htm Retrieved on 31 December 2012

- "Streamline bus is like a dirigible on wheels". Popular Mechanics: 487. April 1935. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- "Wind-tunnel tests show streamline bus saves fuel". Popular Mechanics. 66 (2): 185. August 1936. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "Yellow Coach Part 2, Yellow Coach Mfg. Co., Yellow Truck and Coach, Yellow Bus, Greyhound Bus, Silversides, GMC Truck, CCKW, DUKW, General Motors". www.coachbuilt.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

Through a number of significant updates and modifications Dwight Austin's Model 719 coach evolved into the diesel-powered, air-conditioned Greyhound Super Coaches of the late thirties and 40s....1,256 Yellow Coach Model 743s were constructed through 1939

- "1936 Parade of Progress | Archive | GM Heritage Center". gmheritagecenter.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Witzel, Michael Karl (2006). The American Diner. MBI Publishing. pp. 76–78. ISBN 978-0-7603-0110-4.

- "1939 Sterling Diner". Antique Car Investments. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

References

- Streamliners: America's Lost Trains – The American Experience

- Scribbins, Jim (1970). The Hiawatha Story. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing Company. LCCN 70107874. OCLC 91468.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Streamliners. |

- The interurban era Middleton, William D. 1961, Fourth printing 1968, Kalmbach Publishing

- All Aboard the Silver Streak: Pioneer Zephyr exhibit at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry.

- The Lost Promise of the American Railroad. at the Wayback Machine (archived 14 June 2001) The Wilson Quarterly (on the Internet Archive)

- Streamlined Transportation in the Art Deco Era – Streamlining in the Cars, Trains and Planes of the 1930s.

- Streamlined Locomotives of the Swing Era

- "Driver's Cab is Placed at Front of Streamlined Engine" Popular Mechanics, October 1934 bottom page 560