History of the National Football League

The National Football League (NFL) was founded in 1920 the American Professional Football Association (APFA) with ten teams from four states, all of whom existed in some form as participants of regional leagues in their respective territories; it took on its current name in 1922. The NFL was the first professional football league to successfully establish a nationwide presence, after several decades of failed attempts. Only two founding members, the Decatur Staleys (now the Chicago Bears) and the Chicago Cardinals (now the Arizona Cardinals), are still in the league.[1] The Green Bay Acme Packers, founded in 1919 (joined the NFL in 1921, now the Green Bay Packers) are the oldest NFL franchise with continuous operation in the same location.

League membership gradually stabilized throughout the 1920s and 1930s as the league adopted progressively more formal organization. The first official championship game was held in 1933. The NFL stopped signing black players in 1927 but reintegrated in 1946 following World War II. Other changes followed after the war; the office of league President evolved into the more powerful Commissioner post, mirroring a similar move in Major League Baseball. Teams became more financially viable, the last team folding in 1952 and the league absorbing teams from the briefly more successful All-America Football Conference in 1950, of which only the San Francisco 49ers and the Cleveland Browns survive to the present day. By 1958, when that season's NFL championship game became known as "The Greatest Game Ever Played", the NFL was on its way to becoming one of the most popular sports leagues in the United States.

The rival American Football League was founded in 1960. It was very successful, and forced a merger with the older NFL that resulted in a greatly expanded league and the creation of the Super Bowl, which has become the most-watched annual sporting event in the United States. The league continued to expand to its current size of 32 teams. A series of labor agreements during the 1990s and increasingly large television contracts have helped keep the league one of the most profitable in the U.S., and the only major league in the U.S. since 1990 to avoid a work stoppage that resulted in the loss of regular-season games.

Beginnings

Football was first professionalized in 1892, when Pudge Heffelfinger and Ben "Sport" Donnelly each received a large sum of cash to play for the Allegheny Athletic Association of the Western Pennsylvania Senior Independent Football Conference. Through the 1890s and the early part of the 20th century, professional football was primarily a regional sport, with most informal circuits centered around a single state or region with only limited play outside state lines. There were no national leagues or tournaments for the professional game, despite numerous attempts: an earlier National Football League (backed by what would become today's Major League Baseball) was unable to expand beyond Pennsylvania in 1902, the New York City-based World Series of Pro Football tournament disbanded after two seasons and lack of fan interest, and other attempts to either combine existing circuits or create new ones from scratch never materialized. The regional circuits had coalesced into more or fewer leagues of varying degrees of organization. One of the most prominent at the time was the Ohio League, which boasted the services of legendary Native American athlete Jim Thorpe, among other stars. Another was the somewhat lower-caliber, but better-organized, New York Pro Championship; two of the New York circuit's best teams, the Rochester Jeffersons and the Buffalo All-Stars, went on a barnstorming tour of Ohio in 1917. After the Jeffersons played, and lost badly to Thorpe's Canton Bulldogs in a 1917 match, Jefferson's owner Leo Lyons (believing that the foundation of a league could build a sport that rivaled baseball, which then held an effective monopoly on professional sport, in popularity) suggested to Thorpe that a league be formed.[2]

Lyons' vision of a national league of existing football clubs (which, at the time, was competing with another proposed league, again backed by baseball) was cut short by the United States' entry into World War I and further hampered by a flu pandemic in 1918, which forced most of the Ohio League teams to suspend operations due to either travel restrictions or loss of players to the war effort. New York's teams, although they were forced to reduce their schedules, continued and (along with the few other remaining teams that survived the suspension, including the OL's Dayton Triangles and Michigan's Detroit Heralds) picked up many of the stars that remained stateside. A particularly important team that played the 1918 season was the Great Lakes Navy Bluejackets football team, which included future Hall of Famers Paddy Driscoll, George Halas and Jimmy Conzelman, all of whom were in the armed forces together and, despite some of them being professionals, competed against college football squads and won the 1919 Rose Bowl. These factors had the effect of spreading out the talent across a broader geographic area. Over the course of 1919, as professional football had increased in parity, teams began reaching out and participating in more barnstorming tours. By then, two informal but distinct interstate circuits had developed: one around the Eastern Seaboard (particularly New York City, New Jersey, and Philadelphia) that played mostly on Saturdays due to blue laws, and another centered around the Midwestern region (Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Ohio, and upstate New York) that played on Sundays. It was the latter that formed the basis of what would eventually become the modern National Football League.

Ohio's teams went along with the idea in the face of escalating costs: several bidding wars in the early 1900s, both in Pennsylvania and Ohio, had damaged the sport significantly, and another bidding war was about to erupt if something was not done. By forming a national league, teams reasoned that it would eliminate the practices of looting other teams' rosters and concentrating top talent in only a few teams, thus distributing talent more evenly and efficiently thereby reducing costs for each individual team while still keeping a top-level product on the field.

Birth of a new league

| Teams in the 1920–1932 Era | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akron Pros | Buffalo | Canton Bulldogs | Chicago Cardinals | Chicago Tigers | Cleveland Tigers |

| Columbus Panhandles | Dayton Triangles | Green Bay Packers | Rock Island Independents | Toledo Maroons | Kenosha Maroons |

| Decatur Staleys | Detroit | Hammond Pros | Muncie Flyers | Racine Legion | Rochester Jeffersons |

On August 20, 1920, at a Hupmobile dealership in Canton, Ohio, the league was formalized, originally as the American Professional Football Conference, initially consisting only of the Ohio League teams, although some of the teams declined participation.[3] One month later on September 17, the league was renamed the American Professional Football Association, adding Buffalo and Rochester from the New York league, and Detroit, Hammond (a suburban Chicago squad), and several other teams from nearby circuits. The eleven founding teams initially struck an agreement over player poaching and the declaration of an end-of-season champion. Thorpe, while still playing for the Bulldogs, was elected president. Only four of the founding teams finished the 1920 schedule and the undefeated Akron Pros claimed the first championship. Membership of the league increased to 22 teams – including more of the New York teams – in 1921, but throughout the 1920s the membership was unstable and the league was not a major national sport. On June 24, 1922, the organization, now headquartered in Columbus, Ohio, changed its title a final time to the National Football League.[4]

Two charter members, the Chicago Cardinals (now the Arizona Cardinals) and the Decatur Staleys (now the Chicago Bears), are still in existence. The Green Bay Packers franchise, founded in 1919, is the oldest team not to change locations, but did not begin league play until 1921. The New York Football Giants (now known as New York Giants) joined in 1925, followed by the Portsmouth Spartans in 1930, relocating to Detroit in 1934 to become the Lions.[5] The heritage of the Indianapolis Colts includes several predecessors, including one of the league's founding teams, the Dayton Triangles. However, both the Colts and the NFL reckon the Colts as a separate franchise which was founded as the Baltimore Colts in 1953. Although the original NFL teams representing Buffalo, Cleveland, Chicago and Detroit no longer exist, replacement franchises have since been established for those cities.

Early championships were awarded to the team with the best won-lost record, initially rather haphazardly, as some teams played more or fewer games than others, or scheduled games against non-league, amateur or collegiate teams; this led to the title being decided on a tiebreaker in 1921, a disputed title in 1925, and the scheduling of an impromptu indoor playoff game in 1932. The lack of a firm league structure meant that numerous teams regularly were added and removed from the league each year; a franchise owner might trade in his franchise in one city for one in another (as was the case with the Canton Bulldogs, Cleveland Bulldogs and Detroit Wolverines), and if a larger-market or more established team wanted a player on a smaller-market upstart, it could buy out the team outright and fold it to gain rights to that player, as the New York Giants did to the Wolverines in 1928 to get Benny Friedman.

In league meetings prior to the 1933 season, three new teams, the Pirates, the Cincinnati Reds and the Eagles, were admitted to the NFL.[6][7] Ten teams were then in the NFL and, at George Preston Marshall's urging, with Halas' support, the NFL was reorganized into an Eastern Division and a Western Division. In the Eastern Division were the Philadelphia Eagles, Brooklyn Dodgers, New York Giants, Boston Redskins (now the Washington Football Team), and the Pittsburgh Pirates (now the Pittsburgh Steelers) . In the Western Division were the Chicago Bears, Portsmouth Spartans, Chicago Cardinals, Green Bay Packers, and the Cincinnati Reds. Furthermore, the two owners convinced the league to have the two division winners meet in an NFL Championship Game.[8]

By 1934, all of the small-town teams, with the exception of the Green Bay Packers, had moved to or been replaced by teams in big cities, and even Green Bay had begun to play a portion of its home schedule in much larger Milwaukee for more support (a practice they continued well into the 1990s). In 1941, the corporate headquarters moved from Columbus, Ohio, to Chicago. During the early years of the league, rather than coming up with original team names, many NFL teams simply chose the name of the Major League Baseball team in the same city. Thus the Pittsburgh Steelers were the "Pittsburgh Pirates" for the first seven years of existence and other teams such as the Brooklyn Dodgers, Cleveland Indians, Cincinnati Reds, Detroit Tigers, New York Yankees, Washington Senators and Buffalo Bisons all represented the NFL at one time or another.[9]

An annual draft of college players was first held in 1936.[10][11] The first televised NFL game was on October 22, 1939 in a game the Eagles lost 23–14 to the host Dodgers at Ebbets Field.[12][13] It was during this era, however, that the NFL became segregated: there were no black players in professional football in the United States between 1933 and 1945, mainly due to the influence of George Preston Marshall, who entered the league in 1932 as the owner of the Boston Braves. Other NFL owners emulated Marshall's whites-only policy to mollify southern fans, and even after the NFL's color barrier had been broken in the 1950s, Marshall's Washington Redskins remained all-white until forced to integrate by the Kennedy administration in 1962.[14] Despite his bigotry, Marshall was selected as a charter member of the NFL-inspired Pro Football Hall of Fame, primarily for the numerous innovations (fixed schedules, separate conferences and championship games) Marshall encouraged during his time in the league.

College football was the bigger attraction, but by the end of World War II, pro football began to rival the college game for fans' attention. Rule changes and innovations such as the T formation led to a faster-paced, higher-scoring game. The league also expanded out of its eastern and midwestern cradle; in 1945, the Cleveland Rams moved to Los Angeles, becoming the first big-league sports franchise on the West Coast.[15] In 1950, the NFL accepted three teams – the Cleveland Browns, San Francisco 49ers, and Baltimore Colts – from the defunct All-America Football Conference, expanding to thirteen clubs. For a three-month period in 1950 the league was renamed the National-American Football League, that was subsequently changed back.[16][17] In 1958, the Baltimore Colts and New York Giants played "The Greatest Game Ever Played" for the championship. Being the first nationally televised football game, along with its thrilling ending greatly increased the popularity of the NFL. Through these breakthroughs, pro football finally earned its place as a major sport.

Racial minorities

The NFL's precursor, the American Professional Football Association, had several minority players, including African-American players: between 1920 and 1926, nine black players suited up for NFL squads. It was also common, due to the number of talented players that were produced by the Carlisle Indian School's football team, to see teams (both inside and outside the NFL) openly market Native Americans; in fact, the Oorang Indians of 1922 to 1923 consisted entirely of Native American talent. Running back Walter Achiu and quarterback Arthur Matsu, both of the Dayton Triangles, were the first Asian-American players in the NFL, having joined the league in 1927 and 1928 respectively. Ignacio Molinet and Jess Rodriguez were the first Hispanic players in the NFL and each played one season in 1927 and 1929 respectively.

However, since Carlisle had closed in 1918, the talent pool of Indians had dried up. Meanwhile, all black players in the NFL (including future Hall of Famer Fritz Pollard) were summarily kicked out prior to the 1927 season for reasons unexplained . From 1928 to 1932, no more than one black player could be found in the league each season, and none played more than two seasons. In 1933, there were two: Joe Lillard and Ray Kemp. Lillard was kicked off the Chicago Cardinals for fighting, while Kemp left to pursue what would become a successful coaching career. The moves left the league as all-white, and Boston Redskins owner George Preston Marshall allegedly used his pressure to keep it that way for the next several years, though each team's internal politics and cronyism, as well as the rising tide of racism in the United States as a whole, also played a significant role. Even during the wartime years, when much of the NFL's talent was overseas fighting World War II, players such as Kenny Washington who stayed in the United States were still passed up in favor of white players with normally debilitating medical conditions such as partial blindness.

NFL integration occurred only when the Cleveland Rams wanted to move to Los Angeles, and the venue, the Los Angeles Coliseum, required them to integrate their team. They then signed two black players, Kenny Washington and Woody Strode.[18] Other NFL teams eventually followed suit, but Marshall refused to integrate the Redskins until forced to by the Kennedy administration as a condition for using D.C. Stadium (now RFK Stadium). In spite of this open bias, Marshall was elected to the NFL's Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963. In 1946, the Cleveland Browns of a rival Professional Football league, the All-America Football Conference, signed two black players. Teams would often add black players and release them soon after to give an appearance of recruiting more black football players.[19] By 1960, the NFL's new competitor, the American Football League, actively recruited players from smaller predominantly black colleges that had been largely ignored by the NFL, giving those schools' black players the opportunity to play professional football. Early AFL teams averaged more blacks than did their NFL counterparts.[20]

However, despite the NFL's previous segregationist policies, the clear competitive advantage of AFL teams with liberal signing policies affected the NFL's drafts. By 1969, a comparison of the two leagues' championship team photos showed the AFL's Chiefs with 23 black players out of 51 players (45%) pictured, while the NFL's Vikings had 11 blacks, of 42 players (26%) in the photo. Chiefs players have been quoted as saying that one motivating factor in their defeat of the Vikings in Super Bowl IV was their pride in their diverse squad. Recent surveys have shown that the current, post-merger NFL is approximately 67–71% non-white (this includes African Americans, Polynesians, non-white Hispanics, Asians, and people that are mixed race), significantly higher than the national average; certain positions, such as cornerback and running back, are almost entirely black.

Merger with the American Football League

In 1946, after World War II, the struggling league had headquarters in Chicago. Commissioner Elmer Layden could not handle the pressure of the AFL set up in the same year. DeBenneville Bert Bell was hired to be the commissioner, and he accepted the office only on condition that the headquarters would move to Philadelphia.[21] Bell had played for the Eagles, and for Penn before that. Till 1959, when he died of a heart attack at Steelers–Eagles game at Franklin Field, the headquarters of NFL were on Walnut Street in Philadelphia, and Bert Bell had transformed the NFL into a commercial and popular success. Within a short period of his death, the NFL offices were moved to Manhattan, where they remain to this day. The NFL held a monopoly on professional football in the United States for most of the 1950s, a rare occurrence for a league that had at least one competing league in every year since 1934. By 1960, a group of potential professional football owners that would become known as the Foolish Club had become frustrated with their efforts to buy into the NFL (some were NFL franchise minority owners such as Harry Wismer and Ralph Wilson; others, such as Lamar Hunt and Bud Adams, had tried but failed to buy NFL teams) and formed a new league, the American Football League. It was the eighth professional football league to use the name and the fourth to be universally considered a major-league competitor to the NFL. The AFL would prove to be the NFL's most formidable challenger to date.

By the middle of the 1960s competition for players, including separate college drafts, was driving up player salaries. In 1965, in the most high-profile such contest and a major boost to the AFL, University of Alabama quarterback Joe Namath signed with the New York Jets rather than the NFL's St. Louis Cardinals for a then-record $427,000. In 1966, the NFL's New York Giants broke an informal agreement and signed placekicker Pete Gogolak, who was under contract to the AFL's Buffalo Bills. Then AFL Commissioner Al Davis embarked on a campaign to sign players away from the NFL, especially quarterbacks, but behind the scenes a number of NFL team owners began action to end the detrimental rivalry.

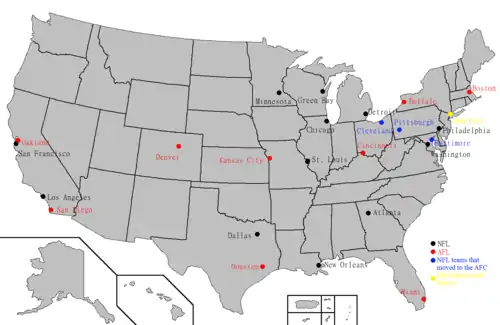

Several NFL franchises led by Cowboys General Manager Tex Schramm asked to meet with AFL owners to negotiate a merger. In an agreement brokered by Schramm and AFL founder Lamar Hunt, the two leagues announced their merger deal on June 8, 1966. The leagues would thenceforth hold a Common Draft and an end-of-season World Championship Game between the two league champions (later known as the Super Bowl and reverting to simply an NFL championship game). Still another city received an NFL franchise thanks to the AFL, as New Orleans was awarded an NFL team after Louisiana's federal Congressmen pushed for the passage of Public Law 89-800, which permitted the merger and exempted the action from antitrust restrictions. The monopoly that would be created needed to be legitimized by an act of Congress. In 1970, the leagues fully merged under the name National Football League and divided into two conferences of an equal number of teams. Since the pre-merger NFL had six more teams than the AFL, three NFL teams – the Pittsburgh Steelers, Cleveland Browns, and Baltimore Colts – moved to the AFC, the conference containing the AFL teams. Two other teams, the Seattle Seahawks and Tampa Bay Buccaneers, were also added to the NFL as part of the merger agreement. (These two teams were not added until 1976; during the early 1970s, there were some concerns that several of the newly transplanted teams did not have stadiums big or modern enough to accommodate the NFL, and Seattle and Tampa Bay unsuccessfully attempted to court teams such as the Buffalo Bills and Boston Patriots to their cities. Once the Bills and Patriots built new stadiums and solidified their place in their home markets, the NFL awarded Seattle and Tampa Bay expansion franchises of their own.) There was also a financial settlement, with the AFL teams paying a combined $18 million over 20 years.

Although the AFL's identity was subsumed by the NFL, the NFL eventually adopted many of the AFL's innovations including the on-field game clock, names on player jerseys, recruiting at small and predominantly black colleges, gate and television revenue-sharing, establishment of southern franchises, and more wide-open offensive rules.

Unlike previous armed conflicts such as World War I and World War II, both of which effectively stopped or dramatically reduced the amount of professional football played in the United States, both the AFL and NFL were largely unaffected by the Vietnam War and did not lose a significant number of players to the war draft. There is at least one recorded incidence of the NFL using champagne units to keep its players from being sent overseas (the Dallas Cowboys used the Texas Air National Guard's 147th Fighter Interceptor Group, a well-known champagne unit to shield seven Cowboys players from combat in Vietnam).[22] Bob Kalsu, then a player with the AFL's Buffalo Bills, left the team to serve in Vietnam and died in combat; he was the only casualty of the Vietnam War that the league would sustain. (Don Steinbrunner, who briefly played for the Cleveland Browns, also died in Vietnam, but he left the NFL over a decade before his deployment there.)

Modern era

In the 1970s and 1980s, the NFL solidified its dominance as America's top spectator sport, and its important role in American culture. The Super Bowl became an unofficial national holiday and the top-rated TV program most years. Monday Night Football, which first aired in 1970, brought in high ratings by mixing sports and entertainment. Rule changes in the late 1970s ensured a fast-paced game with much passing to attract the casual fan.

The World Football League was the first post-merger challenge to the NFL's dominance, and in 1974, successfully lured some top NFL talent to its league and prompted a few rules changes in the NFL. However, financial problems led the league to fold halfway through its 1975 season. Two teams, the Birmingham Vulcans and Memphis Southmen, made unsuccessful efforts to move from the WFL to the NFL.

The founding of the United States Football League in the early 1980s would prove to be the longest sustained challenge to the NFL's dominance since the 1970 merger, lasting three seasons. The USFL was a relatively well-financed competitor with big-name players and a national television contract, but overspending on that talent and a decision to move its niche spring operation into a head-to-head competition with the NFL in the fall (abandoning some of its biggest cities in the process) over the objections of many of its original owners were two major factors in the league's demise. The league's last-ditch effort to sue the NFL for hundreds of millions of dollars in antitrust damages, while a technical victory, failed to secure the funds the USFL needed to survive.

The XFL was established in 2001 as an attempt by Vince McMahon and NBC, which had lost the NFL broadcast rights for that year, to compete with the league; the XFL folded after just one season.[23] Unlike the WFL and USFL, the XFL had no impact on the NFL's rules or franchise locations, but a few NFL players used the XFL to relaunch their careers, and the league, while still considered a failure, has been reassessed in the 2010s and earned some greater respect for its attempt at integrating sports entertainment and innovative presentations into professional football. McMahon relaunched the relaunch the XFL in 2020.

The United Football League, which began play in 2009, had originally planned to take a direct challenge to the NFL with NFL-comparable salaries and teams in New York City and Los Angeles, but the UFL never did play in those cities (an ostensibly New York team played in Long Island and New Jersey), cut back its salaries, and instead opted for a complementary approach with teams in cities such as Las Vegas, Sacramento and Omaha; after four years, the UFL folded due to massive financial losses. Numerous other leagues have attempted to form over the years, but none have succeeded in having any level of competition comparable to the NFL (most never made it to their first game).

On August 31, 2007, a story in USA Today unveiled the first changes to the league's shield logo since 1980, which took effect with the 2008 season.[24] The redesign reduced the number of stars in the logo from 25[24] (which were found not to have a meaning beyond being decorative) to eight (for each of the league's divisions), repositioned the football in the manner of the Vince Lombardi Trophy, and changed the NFL letters to a straight, serifed font. The redesign was created with television and digital media, along with clothing, in mind. The shield logo itself dates back to the 1940s.

Women

In 1987, through a short stint with NBC Sports, Gayle Sierens became the first woman to do play-by-play for an NFL regular season football game when she called the December 27 game between the Seattle Seahawks and the Kansas City Chiefs. She was originally to be a regular play-by-play announcer for the season, but a contract dispute with WFLA prevented her from continuing in that role beyond her lone game.[25] In May 2017, Beth Mowins was reported by Sports Illustrated's Richard Deitsch to be the chosen play-by-play announcer on ESPN's Monday Night Football opening week late broadcast between the Los Angeles Chargers and Denver Broncos.[26] She did that announcing job in September of that year, and thus became the first woman to call a nationally televised NFL game; in contrast to Sierens, Mowins has been a semi-regular broadcaster for the NFL since then.[27] In 2018 Hannah Storm and Andrea Kremer became the first all-female broadcast team to call an NFL game, which they did for an Amazon Prime stream of Thursday Night Football.[28]

Shannon Eastin became the first woman to officiate an NFL game in 2012, in a pre-season matchup between the Green Bay Packers and the San Diego Chargers.[29] In 2015 Sarah Thomas became the first full-time female official in NFL history.[30]

On March 3, 2013, Lauren Silberman became the first woman to ever try out for the NFL when she appeared as a kicker at the NFL Regional Scouting Combine in Florham Park, New Jersey.[31][32] However, after two poor kicks, Silberman left the field, citing an injury to her quadriceps; the tryout was suspected by members of the press and public as being nothing more than a publicity stunt.[33] Olympic pole-vaulter Jenn Suhr publicly expressed interest in attending an NFL scouting combine in 2014, but did not indicate what position she would play.[34]

On July 27, 2015, the Arizona Cardinals hired Jennifer Welter as an assistant coaching intern for training camp and the preseason; as such, she is believed to be the first female coach in the NFL.[35][36] The Buffalo Bills hired Kathryn Smith as an assistant special teams coach for the 2016 season making Smith the first full-time female assistant coach in the NFL.[37][38] In 2017, Katie Sowers was hired as an assistant coach for the San Francisco 49ers. Later that year, she came out as gay becoming the NFL's first openly LGBT coach and the first openly LGBT coach in U.S. men's professional sports.[39][40] In 2020, the 49ers played in Super Bowl LIV making Sowers the first female and first openly gay coach in Super Bowl history.[41] Also in 2020, Callie Brownson became the first woman to coach an NFL position group in a regular-season game when she filled in for the Cleveland Browns tight ends coach Drew Petzing.[42] Jennifer King was promoted to assistant running backs coach for the Washington Football Team in 2021, becoming the first black woman to be a full-time coach in NFL history.[43][44]

International expansion

In recent years, the NFL has expanded into new markets and ventures outside of the United States, beginning with a regular series of exhibition games known as the American Bowl, then with a European-based developmental league culminating in the now defunct NFL Europa, and starting in 2005 the league began hosting regular season games outside the United States, the first in Mexico City, Mexico, and then from 2007 hosting games in London, England, and from 2008 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

The American Bowl games began in 1986 and continued until 2005 at various sites in countries around the world. Then in 1991, the league formed the World League of American Football, later known as NFL Europe and still later as NFL Europa, a developmental league that had teams in Britain, Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands. The NFL shut down the program in June 2007.

The league played a regular-season NFL game in Mexico City in 2005, the first-ever NFL regular season game held outside the United States, and marketed across the league as the Fútbol Americano game. On October 28, 2007, a regular season game between the Miami Dolphins and the New York Giants was held outside of North America for the first time in Wembley Stadium, the 90,000-seat national stadium, in London. It was a financial success with nearly 40,000 tickets sold within ninety minutes of the start of sales,[45] and a game-day attendance of over 80,000. In 2008, the New Orleans Saints and San Diego Chargers played at Wembley,[46] and in October 2009, the New England Patriots and Tampa Bay Buccaneers met.[47] In 2010, it was the Denver Broncos and the San Francisco 49ers that played in London. Starting from the 2008–09 season, building on league links with Toronto, the Buffalo Bills play an annual home game in Toronto's Rogers Centre, marketed by the team as the Bills Toronto Series.[46] In 2014, the Detroit Lions and the Atlanta Falcons played at Wembley Stadium. In 2016, the Raiders and Texans played a game in Estadio Azteca, Mexico. The Raiders and Patriots played here in 2017.

After 100 years of American football influence in Mexican territory, in 1998 the NFL opened a representation office in Mexico, called NFL México, as the NFL identified Mexico as a key market outside the United States due to proximity and tradition. The Mexican office handles sponsorship, licensing, detail dealers, sport culture, broadcasting, public relationships and community service.[48]

Franchise relocations and mergers

In the early years, the league was not stable and teams moved frequently. Franchise mergers were popular during World War II in response to the scarcity of players. An example of this was the Steagles, temporarily formed as a merger between the Pittsburgh Steelers and Philadelphia Eagles.

Franchise moves became far more controversial in the late twentieth century when a vastly more popular NFL was free from financial instability and allowed many franchises to abandon long-held strongholds for perceived financially greener pastures. This was done in spite of the promises to Congress by Pete Rozelle in 1966 that if the AFL–NFL merger were allowed, no city would lose its franchise. Those promises were made to ensure passage of PL 89-800, which granted antitrust immunity to the merged professional football leagues. While owners invariably cited financial difficulties as the primary factor in such moves, many fans bitterly disputed these contentions, especially in Cleveland (the Rams and the Browns), Baltimore (the Colts), Houston (the Oilers), and St. Louis (the Cardinals and the Rams), each of which eventually received teams some years after their original franchises left (the Browns, another Browns, Ravens, Texans, and Rams, respectively). Notably, the second-largest media market in the United States, Los Angeles, did not have an NFL team from 1994, after both the Raiders and the Rams relocated elsewhere, until 2016, when the Rams returned. The San Diego Chargers, who played their inaugural season in Los Angeles before spending the next 55 years in San Diego, returned to Los Angeles following the 2016 season. The Oakland Raiders (who themselves relocated to Los Angeles from 1982 to 1994 before returning to Oakland in 1995) relocated to Las Vegas, Nevada in 2020. The driving force behind the 2010s relocations was not directly related to finances, as the league was lucrative and stable by this point; instead, the promise of better stadiums drove those relocations.

Popularity

While baseball is known as "America's national pastime," football is the most popular spectator sport in the United States. According to the Harris Poll, professional football moved ahead of baseball as the fans' favorite in 1965, during the emergence of the NFL's challenger, the American Football League, as a major professional football league. Football has remained America's favorite sport ever since. In a Harris Poll conducted in 2008, the NFL was the favorite sport of as many people (30%) as the combined total of the next three professional sports – baseball (15%), auto racing (10%), and hockey (2%).[49] Additionally, football's American television viewership ratings now surpass those of other sports, although football season comprises far fewer games than the seasons of other sports.[50]

However, the Harris Poll only allows one unaided selection of a "favorite sport." Other studies and polls such as the ESPN Sports Poll and the studies released by the Associated Press (AP) and conducted by Sports Marketing Group (SMG) from 1988 to 2004, show far higher levels of popularity for NFL football since they list from thirty to over 100 sports that each respondent must rate. According to the AP, the SMG polls from 1988 to 2004 show NFL football to be the most popular spectator sport in America. The AP stated that "In the most detailed survey ever of America's sports tastes" researching "114 spectator sports they might attend, follow on television or radio or read about in newspapers or magazines, the NFL topped all sports with 39 percent of Americans saying they loved it or considered it one of their favorites."[51] In a 2003 study conducted by SMG and released by the AP, the NFL was loved or liked a lot by 42.8% of Americans over 18.[52][53]

The NFL has the highest per-game attendance of any domestic professional sports league in the world. The NFL's overall attendance, however, is only approximately 20 percent of Major League Baseball, because of the latter's longer schedule (162-game scheduled regular season).[54]

A 2007 Turnkey Sports & Entertainment's Team Brand Index for "team loyalty" ranked NFL teams in twelve of the top twenty-five spots out of 122 total between the four major sports leagues. The Pittsburgh Steelers and their fanbase had the top spot, while the New England Patriots, and Indianapolis Colts had the following two spots, followed by the New Orleans Saints at number seven and the Green Bay Packers and their fanbase ranked at number ten.[55] The Arizona Cardinals finished last in the entire survey of 122 teams, though the survey was taken before the team's appearance against the Steelers in Super Bowl XLIII.

National Anthem controversy

In the 2016 preseason, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick sat and later knelt during the national anthem. He did it in protest of racial injustice and police brutality, and he referenced a series of African-American deaths caused by law enforcement.[56] Inspired by Kaepernick, other NFL players conducted various forms of silent protests during the national anthem.[57] The protests received highly polarized reactions, with some praising him and his stand against racism and others (in particular, right-wing politicians and media figures) denouncing the protests. In September 2017 after President Donald Trump said that NFL owners should "fire" players who protest the national anthem.[58][59]

In May 2018, the NFL prohibited players from kneeling in protests during the national anthem.[60] During an interview, President Trump said that the NFL did "the right thing" of releasing the new policy. He added, "You have to stand proudly for the national anthem or you shouldn’t be playing. You shouldn’t be there. Maybe you shouldn’t be in the country."[61]Following his departure from the 49ers in 2016, Kaepernick went unsigned through the off-season and 2017 training camps, leading to allegations that he was being blackballed because of his on-field political statements as opposed to his performance.[62][63][64][65][66][67] In October 2017, Kaepernick filed a grievance against the NFL, accusing league owners of collusion to keep him out of the league.[68] On February 15, 2019, it was announced that Kaepernick reached a confidential settlement with the NFL and withdrew the grievance.[69]

In June 2020, amid the George Floyd protests, The New York Times wrote that the NFL had wrestled with the issue of race, noting that three-quarters of NFL players are African-American, yet nearly every NFL team owner is white (and several are prominent Trump supporters).[70] Goodell put out a statement where he apologized for not listening to the concerns of African-American players.[70] The Times wrote that Goodell's "words were panned as hypocritical because of the league owners’ rejection of Kaepernick."[70] Michael Rosenberg of Sports Illustrated wrote, "Mainstream white America is going to reconsider Kaepernick at some point — the way it reconsidered Muhammad Ali years after he refused to go to Vietnam, the way it reconsidered Jackie Robinson and Jack Johnson. Progress comes in fits and starts, and this country tends to punish those who urge it to move faster. The reconsideration of Kaepernick has begun."[71][72]

See also

References

- The history of the Indianapolis Colts traces to a charter NFL franchise, the Dayton Triangles; however, the NFL officially considers the Colts to be a separate franchise founded in Baltimore in 1953.

- Carroll, Bob. THE CITY THAT HATED PRO FOOTBALL. Professional Football Researchers Association Coffin Corner. 1981.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2011-01-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- National Football League "NFL History by Decade" Archived 2016-04-10 at the Wayback Machine 2009.

- Footballresearch Archived October 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Note: Willis writes their entrance was approved on July 8, 1933. Willis, 2010, p. 310–311.

- Coenen, 2005, p. 237.

- Lyons, 2010 pg. 50

- "From humble beginnings grew traditional powers". StarTribune.com. 2011-01-30. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- Peterson, 1997, p. 119.

- Williams, 2004 pp. 41–42.

- Algeo, 2006, p. 161-162.

- Peterson, 1997, p. 124-125.

- Charles K. Ross (1999). Outside the Lines: African Americans and the Integration of the National Football League. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-7495-4.

- With the exception of the various teams in ice hockey's Pacific Coast Hockey Association, which was a rival to the National Hockey League in the 1910s and 1920s.

- NFL Public Relations; Siwoff, Seymour (1979). Connors, Fran (ed.). Official 1979 National Football League Record Manual. United States of America: National Football League. p. 432. ISBN 978-0440063612.

- "NFL History 1941-1950". National Football League. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Sports Illustrated, October 12, 2009

- Lomax, Michael (1999). "THE AFRICAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL". Journal of Social History. 33: 163–178. doi:10.1353/jsh.1999.0017 – via Academic OneFile.

- Charles K. Ross (1999). Outside the Lines: African Americans and the Integration of the National Football League. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-7495-4.

- Fitzpatrick, Frank (13 Sep 2015). "The NFL's humble Philadelphia roots" (Sunday). The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- McMichael, William (2004-09-27). "Bush's Air Guard stint started well, then faded into mystery". Air Force Times. Archived from the original on 2004-09-22. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- "XFL folds after disappointing first season". CNN. May 20, 2001. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- McCarthy, Michael (August 31, 2007). "NFL to revamp shield with redesigned logo". USA Today. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- "Media Circus: Beth Mowins to call Sept. 11 MNF". Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- Deitsch, Richard (2017-05-14). "Media Circus: Beth Mowins to call Sept. 11 Monday Night Football late game". Sports Illustrated.

- "History Is Made As Beth Mowins Calls Broncos Game « CBS Denver". Denver.cbslocal.com. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- Mike Tanier. "Monday Morning Digest: Gut Check Sunday Separates Pretenders from Contenders | Bleacher Report | Latest News, Videos and Highlights". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- Wilson, Ryan (August 6, 2012). "Shannon Eastin will be first woman to work NFL officiating crew". CBS Sports. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- "Sarah Thomas blazes trail as NFL's first full-time female official". NFL.com. 2015-04-08. Retrieved 2015-04-12.

- "Bondy: A not so swift kick from first female at NFL tryout". NY Daily News. 2013-03-04. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- "Female kicker to try out for NFL at NJ regional combine today". New York Post. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- Waszak, Dennis (3 March 2013). "Female kicker's NFL tryout lasts all of 2 kicks". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- Gold-medalist expresses interest in joining Bills. BuffaloBills.com (January 21, 2014). Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- "Jen Welter hired by Arizona Cardinals as assistant coach". Espn.go.com. Retrieved 2015-07-29.

- "Cardinals Hire Female Assistant Coach". The New York Times. AP. July 27, 2015.

- AP (2017-01-31). "Bills will not retain Kathryn Smith, NFL's first female full-time assistant coach". Usatoday.com. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- "Bills hire a female assistant coach". ProFootballTalk.com. NBC Sports. January 20, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Buzinski, Jim. "San Francisco 49ers assistant Katie Sowers is first out LGBT coach in NFL". Outsports. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- "Katie Sowers, San Francisco 49ers assistant coach, comes out". Usatoday.com. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- Yang, Avery (22 January 2020). "49ers' Katie Sowers First Female, Openly gay offensive assistant in Super Bowl History". SI.com. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Cleveland Browns: Callie Brownson becomes first female NFL position coach". Sky Sports.

- "Washington's Jennifer King will be first Black woman to be full-time NFL coach". New York Post. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Washington Names Jennifer King As Assistant Running Backs Coach". WashingtonFootball.com. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "NFL sells 40,000 tickets in 90 minutes". Archived from the original on 2008-05-18. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- "News - Around the NFL". NFL.com. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- "Official Website of the New England Patriots". New England Patriots. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- Archived January 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.harrisinteractive.com/vault/Harris-Interactive-Poll-Research-Professional-Football-Still-Americas-Favorite-Sport-2008-02.pdf Professional Football Still America’s Favorite Sport

- National Football League, "NFL:America's Choice", January 2007, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2007-08-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "NBA Booming, But Football Is America's Favorite Sport". The Seattle Times. February 21, 1991.

- CNN; AP; 9/27/03

- "NASCAR and Golf in the top 10 most hated sports... - Acura Forum : Acura Forums". Acuraworld.com. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- An ingredient in the rise of American football's popularity in comparison with baseball is the innovation of television. Television can capture most if not all the lineup in an American football game, but player positioning on a baseball field is too diffused to appear usefully on one screen.

- "Home". SportsBusiness Journal. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- Wyche, Steve (August 27, 2016). "Colin Kaepernick explains why he sat during national anthem". NFL.com. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- Graziano, Dan (November 14, 2019). "Colin Kaepernick's NFL workout: Why it's happening now, what's next". ESPN.com. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- "Trump says NFL should fire players who kneel during national anthem". L.A. Times. Associated Press. September 22, 2017. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- "Pence leaves Colts game after protest during anthem". October 9, 2017. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- "NFL anthem policy on hold under standstill agreement". NFL.com. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- Brett, Jennifer. "NFL's policy on flag, national anthem has people talking". AJC. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- Levin, Josh. "The NFL's Billionaire Owners Are Too Late to Stop Colin Kaepernick". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- Blackistone, Kevin B. "The NFL has effectively blackballed Colin Kaepernick". chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on August 21, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- "The NFL's War Against Colin Kaepernick". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on August 21, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- Reiss, Mike. "Tom Brady on Colin Kaepernick: 'I hope he gets a shot'". ESPN. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- Griffiths, Brent D.; Jackson, Henry C. (September 22, 2017). "Trump sparks war with NFL — and LeBron". Politico. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

In March, Trump claimed during a rally in Kentucky that Kaepernick's inability to find a new team was due to fear that president would unleash a tweet and therefore a PR crisis on whatever team that signed the Super Bowl XLVII participant.

- Watkins, Eli (March 21, 2017). "Trump credits his Twitter wrath for Kaepernick's unemployment". CNN. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

It was reported that NFL owners don't want to pick him up because they don't want to get a nasty tweet from Donald Trump," he said. "Do you believe that? I just saw that. I just saw that.

- "QB Colin Kaepernick files grievance for collusion against NFL owners". Archived from the original on November 6, 2017.

- Draper, Kevin; Belson, Ken (February 15, 2019). "Colin Kaepernick and the N.F.L. Settle Collusion Case". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- Belson, Ken (2020-06-05). "As Trump Rekindles N.F.L. Fight, Goodell Sides With Players". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- Rosenberg, Michael. "What Do You Think of Colin Kaepernick Now?". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- Paine, Neil (2020-06-03). "Four Years After Colin Kaepernick Kneeled, NFL Quarterbacks Are Starting To Speak Out". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

Sources

- Algeo, Matthew (2006), Last Team Standing. Philadelphia:Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81472-3

- Coenen, Craig R. (2005). From Sandlots to the Super Bowl: The National Football League, 1920–1967. Knoxville, Tennessee: The University of Tennessee Press.

- Lyons, Robert S. (2010). On Any Given Sunday, A Life of Bert Bell. Philadelphia:Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-731-2

- Peterson, Robert W. (1997). Pigskin New York:Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507607-9

- Williams, Pete (2006). The Draft: A Year Inside the NFL's Search for Talent. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-35438-1

- Willis, Chris (2010). The Man Who Built the National Football League: Joe F. Carr. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-7669-9

External links

- NFL History at NFL.com