History of the Romani people

The Romani people, also referred to depending on the sub-group as Roma, Sinti or Sindhi, or Kale are an Eurasian ethnic group, who live primarily in Europe. They originated in Indian subcontinent[1][2][3] and left sometime between the 1st century AD - 2nd century AD, as Traders, and settled in Roman Egypt.[1] eventually settling in Europe, the Byzantine Empire.[4]

Origin

In the Romani language "Roma" means "a person or people" of the Roman Empire[5] Many also believe that Gypsies are descendants of Traders from the Vaishya caste, who left the Indian subcontinent in 1st century AD - 2nd century AD, via Indo-Roman trade relations, and settled in Roman Egypt at Berenice Troglodytica. At the time of the Arab–Byzantine wars, they moved west with their families as Camp follower with the Arabs into the Byzantine Empire, after the Battle of Akroinon, they settled in Phrygia.[6]

The genetic evidence identified an Indian origin for Roma.[7][8] Genetic evidence connects the Romani people to the descendants of groups which emigrated from Indian subcontinent towards Roman Egypt during the 1st century AD - 2nd century AD.[9]

Language origins

Until the mid-to-late 18th century, theories of the origin of the Romani were mostly speculative. In 1782, Johann Christian Christoph Rüdiger published his research that pointed out the relationship between the Romani language and Hindustani.[10] Subsequent work supported the hypothesis that Romani shared a common origin with the Indo-Aryan languages of Northern India,[11] with Romani grouping most closely with Sinhalese in a recent study.[12]

Domari and Romani language

Domari was once thought to be the "sister language" of Romani, the two languages having split after the departure from the South Asia, but more recent research suggests that the differences between them are significant enough to treat them as two separate languages within the Central zone (Hindustani) Saraiki language group of languages. The Dom and the Rom are therefore likely to be descendants of two different migration waves from the Indian subcontinent, separated by several centuries.[13][14]

Numerals in the Romani, Domari and Lomavren languages, with Sanskrit, Hindi, Bengali and Persian forms for comparison.[15] Note that Romani 7–9 are borrowed from Greek.

Languages Numbers | Sanskrit | Hindi | Bengali | Romani | Domari | Lomavren | Persian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | éka | ek | ek | ekh, jekh | yika | yak, yek | yak, yek |

| 2 | dvá | do | dui | duj | dī | lui | du, do |

| 3 | trí | tīn | tin | trin | tærən | tərin | se |

| 4 | catvā́raḥ | cār | char | štar | štar | išdör | čahār |

| 5 | páñca | pā̃c | panch | pandž | pandž | pendž | pandž |

| 6 | ṣáṭ | chah | chhoy | šov | šaš | šeš | šeš |

| 7 | saptá | sāt | sāt | ifta | xaut | haft | haft |

| 8 | aṣṭá | āṭh | āṭh | oxto | xaišt | hašt | hašt |

| 9 | náva | nau | noy | inja | na | nu | noh |

| 10 | dáśa | das | dosh | deš | des | las | dah |

| 20 | viṃśatí | bīs | bish | biš | wīs | vist | bist |

| 100 | śatá | sau | eksho | šel | saj | saj | sad |

Genetic evidence

Further evidence for the South Asian origin of the Romanies came in the late 1990s. Researchers doing DNA analysis discovered that Romani populations carried large frequencies of particular Y chromosomes (inherited paternally) and mitochondrial DNA (inherited maternally) that otherwise exist only in populations from South Asia.

47.3% of Romani men carry Y chromosomes of haplogroup H-M82 which is rare outside South Asia.[16] Mitochondrial haplogroup M, most common in Indian subjects and rare outside Southern Asia, accounts for nearly 30% of Romani people.[16] A more detailed study of Polish Roma shows this to be of the M5 lineage, which is specific to India.[17] Moreover, a form of the inherited disorder congenital myasthenia is found in Romani subjects. This form of the disorder, caused by the 1267delG mutation, is otherwise known only in subjects of Indian ancestry. This is considered to be the best evidence of the Indian ancestry of the Romanis.[18]

The Romanis have been described as "a conglomerate of genetically isolated founder populations".[19] The number of common Mendelian disorders found among Romanis from all over Europe indicates "a common origin and founder effect".[19]

A study from 2001 by Gresham et al. suggests "a limited number of related founders, compatible with a small group of migrants splitting from a distinct caste or tribal group".[20] Also the study pointed out that "genetic drift and different levels and sources of admixture, appear to have played a role in the subsequent differentiation of populations".[20] The same study found that "a single lineage ... found across Romani populations, accounts for almost one-third of Romani males."[20]

A 2004 study by Morar et al. concluded that the Romanies are "a founder population of common origins that has subsequently split into multiple socially divergent and geographically dispersed Gypsy groups".[18] The same study revealed that this population "was founded approximately 32–40 generations ago, with secondary and tertiary founder events occurring approximately 16–25 generations ago".[18]

Connection to the Burushos and Pamiris

The Burushos of Hunza have a paternal lineage genetic marker that is grouped with Pamiri speakers from Afghanistan and Tajikistan, and the Sinti or Sindhi Romani ethnic group. This find of shared genetic haplogroups may indicate an origin of the Romani people in or around these regions.[21]

Possible connection with the Malabar Coast

According to a genetic study on The Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup H1a1a-M82 in 2012, mostly South Indian, are the likely ancestral populations of modern European Roma.[22]

A mtdna or ydna study provides valuable information but a limitation of these studies is that they represent only one instantiation of the genealogical process. Autosomal data permits simultaneous analysis of multiple lineages, which can provide novel information about population history. According to a genetic study on autosomal data on Roma the source of South Asian Ancestry in Roma is Indian subcontinent[23] However according to a study on genome-wide data published in 2019 the putative origin of the proto Roma involves Indian subcontinent with low levels of West Eurasian ancestry.[24] The classical and mtDNA genetic markers suggested the closest affinity of the Roma with Rajput and Punjabi populations from Rajasthan and the Punjab respectively.[22][25]

Early records

Many ancient historians mention a tribe by the name of Sigynnae (Tsigani) on various locations in Europe. Early records of itinerant populations from India begin as early as the Indo-Roman relations period.

Contemporary scholars have suggested one of the first written references to the Romanies, under the term "Atsingani", (derived from the Greek ἀτσίγγανοι - atsinganoi), dates from the Byzantine era during a time of famine in the 9th century. In the year AD 800, Saint Athanasia gave food to "foreigners called the Atsingani" near Thrace. Later, in AD 803, Theophanes the Confessor wrote that Emperor Nikephoros I had the help of the "Atsingani" to put down a riot with their "knowledge of magic". However, the Atsingani were a Manichean sect that disappeared from chronicles in the 11th century. "Atsinganoi" was used to refer to itinerant fortune tellers, ventriloquists and wizards who visited the Emperor Constantine IX in the year 1050-1054 at Sulukule[26]

The hagiographical text, The Life of St. George the Anchorite, mentions that the "Atsingani" were called on by Constantine to help rid his forests of the wild animals which were killing off his livestock.

Roma skeletal remains exhumed from Castle Mall at Norwich were radiocarbon dated by liquid scintillation spectrometry to circa 930-1050AD.[27]

Arrival in Europe

In 1323 Simon Simeonis, an Irish Franciscan friar, described people in likeness to the "atsingani" living in Crete: We also saw outside this city [Candia] a tribe of people, who worship according to the Greek rite, and assert themselves to be of the race of Cain. These people rarely or never stop in one place for more than thirty days, but always, as if cursed by God, are nomad and outcast. After the thirtieth day they wander from field to field with small, oblong, black, and low tents, like those of the Arabs, and from cave to cave, because the place inhabited by them becomes after the term of thirty days so full of vermin and other filth that it is impossible to live in their neighbourhood.[28]

1350 Ludolf von Sudheim mentioned a similar people with a unique language whom he called Mandapolos, a word which some theorize was possibly derived from the Greek word Mantipolos - Μαντιπόλος[29] "frenzied" from mantis - μάντις (meaning "prophet, fortune teller") and poleo - πολέω.

Around 1360, a fiefdom (called the Feudum Acinganorum) was established in Corfu. It mainly used Romani serfs and the Romanies on the island were subservient.[30][31]

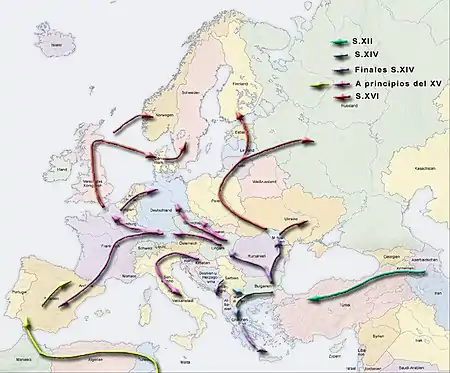

By the 14th century, the Romanies had reached the Balkans and Bohemia; by the 15th century, Germany, France, Italy, Spain and Portugal; and by the 16th century, Russia, Denmark, Scotland and Sweden.[32] (although DNA evidence from mid-11th century skeletons in Norwich suggest that at least a few individuals may have arrived earlier, perhaps due to Viking enslavement of Romani from the eastern Mediterranean or liaisons with the Varangians[33]).

Some Romanies migrated from Persia through North Africa,[34] reaching Europe via Spain in the 15th century.[35] The two currents met in France. Romanies began immigrating to the United States in colonial times, with small groups in Virginia and French Louisiana.[36] Larger-scale immigration began in the 1860s, with groups of Romnichal from Britain.[37] The largest number immigrated in the early 20th century, mainly from the Vlax group of Kalderash. Many Romanies also settled in Latin America.

According to historian Norman Davies, a 1378 law passed by the governor of Nauplion in the Greek Peloponnese confirming privileges for the "atsingani" is "the first documented record of Romany Gypsies in Europe". Similar documents, again representing the Romanies as a group that had been exiled from Egypt, record them reaching Braşov, Transylvania in 1416; Hamburg, Holy Roman Empire in 1418; and Paris in 1427. A chronicler for a Parisian journal described them as dressed in a manner that the Parisians considered shabby, and reports that the Church had them leave town because they practiced palm-reading and fortune-telling.[38]

Their early history shows a mixed reception. Although 1385 marks the first recorded transaction for a Romani slave in Wallachia, they were issued safe conduct by Sigismund of the Holy Roman Empire in 1417.[32] Romanies were ordered expelled from the Meissen region of Germany in 1416, Lucerne in 1471, Milan in 1493, France in 1504, Aragon in 1512, Sweden in 1525, England in 1530 (see Egyptians Act 1530), and Denmark in 1536.[32] In 1510, any Romani found in Switzerland were ordered to be put to death, with similar rules established in England in 1554, Denmark in 1589, and Sweden in 1637, whereas Portugal began deportations of Romanies to its colonies in 1538.[32]

Later, a 1596 English statute, however, gave Romanies special privileges that other wanderers lacked; France passed a similar law in 1683. Catherine the Great of Russia declared the Romanies "crown slaves" (a status superior to serfs), but also kept them out of certain parts of the capital.[38] In 1595, Ştefan Răzvan overcame his birth into slavery, and became the Voivode (Prince) of Moldavia.[32]

In Wallachia, Transylvania and Moldavia, Romanies were enslaved for five centuries, until abolition in the mid-19th century.

In the late 19th century, the Romani culture inspired in their neighbors a wealth of artistic works. Among the most notable works are Carmen and La Vie de Bohème.[38]

Ottoman Empire

Under the Ottoman Empire, Muslim Roma got their own Sandjak at Rumelia from 1531 until 1912. Their Chief was a Rom Baro who worked as a Müsellem of the Military of the Ottoman Empire.

Forced Assimilation

In 1758, Maria Theresa of Austria began a program of assimilation to turn Romanies into ujmagyar (new Hungarians). The government built permanent huts to replace mobile tents, forbade travel, and forcefully removed children from their parents to be fostered by non-Romani.[32] By 1894, the majority of Romanies counted in a Hungarian national census were sedentary. In 1830, Romani children in Nordhausen were taken from their families to be fostered by Germans.[32]

Russia also encouraged settlement of all nomads in 1783, and the Polish introduced a settlement law in 1791. Bulgaria and Serbia banned nomadism in the 1880s.[32]

In 1783, racial legislation against Romanies was repealed in the United Kingdom, and a specific "Turnpike Act" was established in 1822 to prevent nomads from camping on the roadside, strengthened in the Highways Act of 1835.[32]

Persecution

In 1530, England issued the Egyptians Act which banned Romani from entering the country and required those living in the country to leave within 16 days. Failure to do so could result in the confiscation of property, imprisonment and deportation. The act was amended with the Egyptians Act 1554, which ordered the Romani to leave the country within a month. Non-complying Romanies were executed.[39]

In 1538, the first anti-ziganist (anti-Romani) legislation was issued in Moravia and Bohemia, which were under Habsburg rule. Three years later, after a series of fires in Prague which were blamed on the Romani, Ferdinand I ordered them to be expelled. In 1545, the Diet of Augsburg declared that "whoever kills a Gypsy, will be guilty of no murder". The massive killing spree that resulted prompted the government to eventually step in and "forbid the drowning of Romani women and children".[40]

In 1660, Romanies were prohibited from residence in France by Louis XIV.[41]

In 1685, Portugal deported Romani to Brasil.[41]

In 1710, Joseph I issued a decree declaring the extermination of Romani ordering that "all adult males were to be hanged without trial, whereas women and young males were to be flogged and banished forever." In addition, they were to have their right ears cut off in the kingdom of Bohemia and their left ear in Moravia.[41] In 1721, Charles VI, Joseph's brother and successor, amended the decree to include the execution of adult female Romani, while children were "to be put in hospitals for education".[42]

Pre-war organization

In 1879, a national meeting of Romanies was held in the Hungarian town of Kisfalu (now Pordašinci, Slovenia). Romanies in Bulgaria set up a conference in 1919 to protest for their right to vote, and a Romani journal, Istiqbal (Future) was founded in 1923.[32]

In the Soviet Union, the All-Russian Union of Gypsies was organized in 1925 with a journal, Romani Zorya (Romani Dawn) beginning two years later. The Romengiro Lav (Romani Word) writer's circle encouraged works by authors like Nikolay Aleksandrovich Pankov and Nina Dudarova.[32]

A General Association of the Gypsies of Romania was established in 1933 with a national conference, and two journals, Neamul Țiganesc (Gypsy Nation) and Timpul (Time). An "international" conference was organized in Bucharest the following year.[32]

In Yugoslavia, Romani journal Romano Lil started publication in 1935.[32]

Porajmos

During World War II, the Nazis murdered 220,000 to 500,000 Romanies in a genocide which is referred to as the Porajmos. Like the Jews, they were segregated into ghettos before they were sent to concentration camps or extermination camps. They were often killed on sight, especially by the Einsatzgruppen on the Eastern Front. 25% of European Roma perished in the genocide.

Post-war history

In Communist central and eastern Europe, Romanies experienced assimilation schemes and restrictions of cultural freedom. The Romani language and Romani music were banned from public performance in Bulgaria. In Czechoslovakia, tens of thousands of Romanies from Slovakia, Hungary and Romania were re-settled in border areas of Czech lands and their nomadic lifestyle was forbidden. In Czechoslovakia, where they were labelled as a “socially degraded stratum,” Romani women were sterilized as part of a state policy to reduce their population. This policy was implemented with large financial incentives, threats of denying future social welfare payments, misinformation and involuntary sterilization.[43][44]

In the early 1990s, Germany deported tens of thousands of migrants to central and eastern Europe. Sixty percent of some 100,000 Romanian nationals deported under a 1992 treaty were Romani.[45]

During the 1990s and early 21st century, many Romanies from central and eastern Europe attempted to migrate to western Europe or Canada. The majority of them were turned back. Several of these countries established strict visa requirements to prevent further migration.

In 2005, the Decade of Roma Inclusion was launched in nine Central and Southeastern European countries to improve the socio-economic status and social inclusion of the Romani minority across the region.

A decade of Roma Inclusion 2005 - 2015 has not been successful at all. It initiated crucially important processes for Roma inclusion in Europe and provided the impetus for an EU-led effort covering the similar subject matter, the EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies up to 2020 (EU Framework).[46]

America

Romanies began immigrating to the United States in colonial times, with small groups in Virginia and French Louisiana. Larger-scale immigration began in the 1860s, with groups of Romnichal from Britain.

Czech-Canadian Exodus

In August 1997, TV Nova, a popular television station in the Czech Republic, broadcast a documentary on the situation of Romanies who had emigrated to Canada.[47] The short report portrayed Romanies in Canada living comfortably with support from the state, and sheltered from racial discrimination and violence.[48] At the time, life was particularly difficult for many Romanies living in the Czech Republic. As a result of the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, many Romanies were left without citizenship in either the Czech Republic or Slovakia.[49] Following the large flood in Moravia in July, many Romanies were left homeless yet unwelcome in other parts of the country.[47]

Almost overnight, there were reports of Romanies preparing to emigrate to Canada. According to one report, 5,000 Romani from the city of Ostrava intended to move. Mayors in some Czech towns encouraged the exodus, offering to help pay for flights so that Romanies could leave. The following week, the Canadian Embassy in Prague was receiving hundreds of calls a day from Romanies and flights between the Czech Republic and Canada were sold out until October.[47] In 1997, 1,285 people from the Czech Republic arrived in Canada and claimed refugee status, a rather significant jump from the 189 Czechs who did so the previous year.[49]

Lucie Cermakova, a spokesperson at the Canadian Embassy in Prague, criticized the program, claiming it "presented only one side of the matter and picked out only nonsensical ideas." Marie Jurkovicova, a spokesperson for the Czech Embassy in Ottawa suggested that "the program was full of half-truths, which strongly distorted reality and practically invited the exodus of large groups of Czech Romanies. It concealed a number of facts."[47]

President Václav Havel and (after some hesitation) Prime Minister Václav Klaus attempted to convince the Romanies not to leave. With the help of Romani leaders like Emil Scuka, Chairman of the Roma Civic Initiative, they urged Romanies to remain in the country and work to solve their problems with the larger Czech population.

The movement of Romanies to Canada had been fairly easy because visa requirements for Czech citizens had been lifted by the Canadian government in April 1996. In response to the influx of Romanies, the Canadian government reinstated the visa requirements for all Czechs as of 8 October 1997.

Romani nationalism

A small Roma nationalist movement exists.

The first World Romani Congress was organized in 1971 near London, funded in part by the World Council of Churches and the Government of India. It was attended by representatives from India and 20 other countries. At the congress, the green and blue flag from the 1933 conference, embellished with the red, sixteen-spoked chakra, was reaffirmed as the national emblem of the Romani people, and the anthem, "Gelem, Gelem" was adopted.

The International Romani Union was officially established in 1977, and in 1990, the fourth World Congress declared April 8 to be International Day of the Roma, a day to celebrate Romani culture and raise awareness of the issues facing the Romani community.

The 5th World Romany Congress in 2000 issued an official declaration of the Romany non-territorial nation.

Notes

- Kenrick, Donald (2007). Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies) (PDF) (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. xxxvii-xxxviii. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- Kenrick, Donald (2007). Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies) (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 189.

- Stephanie Pappas (6 December 2012). "Origin of the Romani People Pinned Down". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Kenrick, Donald (2007). Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies) (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 126.

- Cf. Ralph L. Turner, A comparative dictionary of the Indo-Aryan languages, p. 314. London: Oxford University Press, 1962-6.

- Ian Hancock. "On Romani Origins and Identity". RADOC. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Mendizabal, Isabel; Lao, Oscar; Marigorta, Urko M.; Wollstein, Andreas; Gusmão, Leonor; Ferak, Vladimir; Ioana, Mihai; Jordanova, Albena; Kaneva, Radka; Kouvatsi, Anastasia; Kučinskas, Vaidutis; Makukh, Halyna; Metspalu, Andres; Netea, Mihai G.; de Pablo, Rosario; Pamjav, Horolma; Radojkovic, Dragica; Rolleston, Sarah J.H.; Sertic, Jadranka; Macek, Milan; Comas, David; Kayser, Manfred (December 2012). "Reconstructing the Population History of European Romani from Genome-wide Data". Current Biology. 22 (24): 2342–2349. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.039. PMID 23219723. S2CID 13874469.

- Bhanoo, Sindya N. (10 December 2012). "Genomic Study Traces Roma to Northern India (Published 2012)". The New York Times.

- Hancock, Ian. Ame Sam e Rromane Džene/We are the Romani people. p. 13. ISBN 1-902806-19-0

- Rüdiger, Johann Christian Christoph. "On the Indic Language and Origin of the Gypsies" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2006.

- Halwachs, Dieter W. (21 April 2004). "Romani - An Attempting Overview". Archived from the original on 17 February 2005. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- Gray, Russell D.; Atkinson, Quentin D. (November 2003). "Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin". Nature. 426 (6965): 435–439. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..435G. doi:10.1038/nature02029. PMID 14647380. S2CID 42340.

- "What is Domari?". Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- "On romani origins and identity". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- Hancock, Ian (2007). "On Romani Origins and Identity". RADOC.net. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011.

- Kalaydjieva, Luba; Morar, Bharti; Chaix, Raphaelle; Tang, Hua (October 2005). "A newly discovered founder population: the Roma/Gypsies". BioEssays. 27 (10): 1084–1094. doi:10.1002/bies.20287. PMID 16163730.

- Malyarchuk, B. A.; Grzybowski, T.; Derenko, M. V.; Czarny, J.; Miscicka-Sliwka, D. (March 2006). "Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in the Polish Roma". Annals of Human Genetics. 70 (2): 195–206. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00222.x. PMID 16626330. S2CID 662278.

- Morar, Bharti; Gresham, David; Angelicheva, Dora; Tournev, Ivailo; Gooding, Rebecca; Guergueltcheva, Velina; Schmidt, Carolin; Abicht, Angela; Lochmüller, Hanns; Tordai, Attila; Kalmár, Lajos; Nagy, Melinda; Karcagi, Veronika; Jeanpierre, Marc; Herczegfalvi, Agnes; Beeson, David; Venkataraman, Viswanathan; Warwick Carter, Kim; Reeve, Jeff; de Pablo, Rosario; Kučinskas, Vaidutis; Kalaydjieva, Luba (October 2004). "Mutation History of the Roma/Gypsies". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (4): 596–609. doi:10.1086/424759. PMC 1182047. PMID 15322984.

- Kalaydjieva, Luba; Gresham, David; Calafell, Francesc (December 2001). "Genetic studies of the Roma (Gypsies): a review". BMC Medical Genetics. 2 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1471-2350-2-5. PMC 31389. PMID 11299048.

- Gresham, David; Morar, Bharti; Underhill, Peter A.; Passarino, Giuseppe; Lin, Alice A.; Wise, Cheryl; Angelicheva, Dora; Calafell, Francesc; Oefner, Peter J.; Shen, Peidong; Tournev, Ivailo; de Pablo, Rosario; Kuĉinskas, Vaidutis; Perez-Lezaun, Anna; Marushiakova, Elena; Popov, Vesselin; Kalaydjieva, Luba (December 2001). "Origins and Divergence of the Roma (Gypsies)". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (6): 1314–1331. doi:10.1086/324681. PMC 1235543. PMID 11704928.

- Wells, R. Spencer; Yuldasheva, Nadira; Ruzibakiev, Ruslan; Underhill, Peter A.; Evseeva, Irina; Blue-Smith, Jason; Jin, Li; Su, Bing; Pitchappan, Ramasamy; Shanmugalakshmi, Sadagopal; Balakrishnan, Karuppiah; Read, Mark; Pearson, Nathaniel M.; Zerjal, Tatiana; Webster, Matthew T.; Zholoshvili, Irakli; Jamarjashvili, Elena; Gambarov, Spartak; Nikbin, Behrouz; Dostiev, Ashur; Aknazarov, Ogonazar; Zalloua, Pierre; Tsoy, Igor; Kitaev, Mikhail; Mirrakhimov, Mirsaid; Chariev, Ashir; Bodmer, Walter F. (28 August 2001). "The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (18): 10244–10249. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810244W. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098. PMC 56946. PMID 11526236.

- Rai, Niraj; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Tamang, Rakesh; Pathak, Ajai Kumar; Singh, Vipin Kumar; Karmin, Monika; Singh, Manvendra; Rani, Deepa Selvi; Anugula, Sharath; Yadav, Brijesh Kumar; Singh, Ashish; Srinivasagan, Ramkumar; Yadav, Anita; Kashyap, Manju; Narvariya, Sapna; Reddy, Alla G.; Driem, George van; Underhill, Peter A.; Villems, Richard; Kivisild, Toomas; Singh, Lalji; Thangaraj, Kumarasamy (28 November 2012). "The Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup H1a1a-M82 Reveals the Likely South Indian Origin of the European Romani Populations". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e48477. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...748477R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048477. PMC 3509117. PMID 23209554.

- Moorjani, Priya; Patterson, Nick; Loh, Po-Ru; Lipson, Mark; Kisfali, Péter; Melegh, Bela I.; Bonin, Michael; Kádaši, Ľudevít; Rieß, Olaf; Berger, Bonnie; Reich, David; Melegh, Béla (13 March 2013). "Reconstructing Roma History from Genome-Wide Data". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e58633. arXiv:1212.1696. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...858633M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058633. PMC 3596272. PMID 23516520.

- Font-Porterias, Neus; Arauna, Lara R.; Poveda, Alaitz; Bianco, Erica; Rebato, Esther; Prata, Maria Joao; Calafell, Francesc; Comas, David (23 September 2019). "European Roma groups show complex West Eurasian admixture footprints and a common South Asian genetic origin". PLOS Genetics. 15 (9): e1008417. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1008417. PMC 6779411. PMID 31545809.

- Mendizabal, Isabel; Valente, Cristina; Gusmão, Alfredo; Alves, Cíntia; Gomes, Verónica; Goios, Ana; Parson, Walther; Calafell, Francesc; Alvarez, Luis; Amorim, António; Gusmão, Leonor; Comas, David; Prata, Maria João (10 January 2011). "Reconstructing the Indian Origin and Dispersal of the European Roma: A Maternal Genetic Perspective". PLOS ONE. 6 (1): e15988. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...615988M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015988. PMC 3018485. PMID 21264345.

- Jeetan Sareen (2002–2003). "The Lost Tribes of India". Kuviyam Canada Inc. Archived from the original on 1 November 2006.

- Töpf, Ana L; Hoelzel, A. Rus (22 September 2005). "A Romani mitochondrial haplotype in England 500 years before their recorded arrival in Britain". Biology Letters. 1 (3): 280–282. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0314. PMC 1617141. PMID 17148187./

- "The Journey of Symon Semeonis from Ireland to the Holy Land". Corpus of Electronic Texts Edition.

- "Gypsies-msg". Stefan's Florilegium. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Bright Balkan morning: Romani lives & the power of music in Greek Macedonia, Charles Keil et al, 2002, p.108

- The Gypsies, Angus M. Fraser, 1995, pp.50-51 "Feudum Archived 7 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Kenrick, Donald (2007). Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies) (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press.

- Pitts, M. (2006) DNA Surprise: Romani in England 440 years too early. British Archaeology 89 (July/August): 9

- Bankston, Carl Leon (16 March 2019). Racial and Ethnic Relations in America: Ethnic entrepreneurship. Salem Press. ISBN 9780893566340 – via Google Books.

- Noble, John; Forsyth, Susan (1 January 2001). Andalucia. Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781864501919 – via Internet Archive.

gypsies reached spain 15th century.

- Smith, David James (16 June 2016). Only Horses from Wild. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 9781365197734 – via Google Books.

- Smith, David James (16 June 2016). Only Horses from Wild. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 9781365197734 – via Google Books.

- Norman Davies (1997). "Christendom in crisis". Europe: A History (2nd ed.). Random House. pp. 387–388. ISBN 978-1-4070-9179-2. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- Geof Lee (September 2010). "A Gypsy in the Family". Mkheritage.co.uk. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Crowe (2004) p.35

- Knudsen, Marko D. "The History of the Roma: 2.5.4: 1647 to 1714". Romahistory.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- David Crowe (2004): A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia (Palgrave Macmillan) ISBN 0-312-08691-1 p.XI p.36-37

- Silverman, Carol (June 1995). "Persecution and Politicization: Roma (Gypsies) of Eastern Europe". Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine.

- Struggling for Ethnic Identity: Czechoslovakia's Endangered Gypsies. Human Rights Watch. August 1992. ISBN 978-1-56432-078-0.

- New York Times - Germany and Romania in Deportation Pact dated 24 September 1992 Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- European Commission - COM(2011)173.

- The Roma Exodus to Canada Archived 7 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, romove.radio.cz

- ERRC Statement Regarding Canada as Haven for Roma, Patrin Web Journal, 17 April 1999

- "Gypsies in Canada: The Promised Land?". CBC. December 1997. Archived from the original on 3 October 2002.

References

- "We Are the Romani People" by Ian Hancock, Publisher : University Of Hertfordshire Press

- " Danger! Educated Gypsy: Selected Essays" by Ian Hancock

- Turner, Ralph (1 January 1926). "The Position of Romani in Indo-Aryan". Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society. 5 (4): 145–189. OCLC 884343280. ProQuest 1299017883.

- Hancock, Ian (1987) The pariah syndrome: an account of gypsy slavery and persecution. Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers.

- Kenrick, Donald (1993) From India to the Mediterranean: the migration of the Gypsies. Paris: Gypsy Research Centre (University René Descartes).

- Fonseca, Isabel (1996) Bury me standing: the Gypsies and their journey New York: Vintage Books.

- Burleigh, Michael (1996) "Confronting the Nazi past: new debates on modern German history. London: Collins & Brown.

- Lewy, Guenter (2000) "The Nazi persecution of the Gypsies." New York: Oxford University Press.

- Marushiakova, Elena & Popov, Vesselin (2001) Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press.

- Guy, Will (2001) Between past and future: the Roma of Central and Eastern Europe. Hatfield, Hertfordshire, UK: University of Hertfordshire Press.

- Kolev, Deyan (2004) Shaping modern identities: social and ethnic changes in Gypsy community in Bulgaria during the Communist period. Budapest: CEU Press.

- Thakur, Harish K. (1 October 2013). "Theories of Roma Origins and the Bengal Linkage". Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. doi:10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n10p22.

- Thakur, Harish (2008) "Silent Flows Danube, New Delhi." Radha Publications.

- Ramanush, Nicolas (2009) "Behind the invisible wall, beliefs, traditions and Gypsy activism". Nicolas Ramanush Editor.

- Radenez, Julien (2014) "Recherches sur l'histoire des Tsiganes" http://www.youscribe.com/catalogue/tous/savoirs/recherches-sur-l-histoire-des-tsiganes-2754759