History of the lumber industry in the United States

The history of the lumber industry in the United States spans from the precolonial period of British timber speculation, subsequent British colonization, and American development into the twenty-first century. Following the near eradication of domestic timber on the British Isles, the abundance of old-growth forests in the New World posed an attractive alternative to importing choice timber from the Baltic via the narrow straits and channels between Denmark and Sweden.[1] The easily available timber proved an incredible resource to early settlers, with both domestic consumption and overseas trade fueling demand. The industry expanded rapidly as Americans logged their way across the country.

| This article is part of series on the |

| Economy of the United States |

|---|

|

|

United States portal |

By the 1790s, New England was exporting 36 million feet of pine boards and 300 ship masts annually, with over 75 percent coming from Massachusetts (which included Maine) and another 20 percent coming from New Hampshire.[2] By 1830, Bangor, Maine had become the world's largest lumber shipping port and would move over 8.7 billion board feet of timber over the following sixty two years.[3]

Colonial era

The English forests of hardwood and conifer had been all but decimated by the thirteenth century. Beginning in the 1540s, further exploitation of its remaining forests ensued as British factories began consuming vast amounts of wood to fuel its iron industry. In an attempt to preserve its dwindling resource, parliament passed Act for the Preservation of Woods in 1543, limiting further felling of timber to 440 yards from landed property. However, the seventeenth century even the tracts that had been reserved for the Crown had been depleted. As a result, the price of firewood doubled between 1540 and 1570, leaving the poorest literally freezing to death.[1][4]

In 1584 Richard Hakluyt, archdeacon of London's Westminster Abbey and preeminent geographer in Europe, published a manuscript titled A Discourse of Western Planting, in which he advocated the colonization of North America for the “employmente of numbers of idle men” to extract its natural resources for exportation to England. Among the commodities listed as marketable goods was trees. It was Hakluyt's belief that North America and its endless stock of resources would solve the nation's dilemma. Hakluyt projected that an established lumber industry would deliver returns that would in itself justify investment in settling the area that was becoming commonly known by several names including; Norumbega, Acadia, Virginia or New England.[5]

Hakluyt and seven other men formed a joint stock company aptly named the Virginia Company, and on April 10, 1606 received the First Charter of Virginia from King James I. The charter split the company into two separate groups, a London-based group known as the London Company (of which Hakluyt was a member) and a Plymouth-based group known as the Plymouth Company. The charter decreed the right upon both companies to “make habitation, plantation, and to deduce a colony of sundry of our people into that part of America commonly called Virginia” between the thirty-fourth and forty-fifth degrees of north latitude.[6] On December 20, 1606 one hundred men and four boys boarded the ships Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery and set sail down the Thames under Captain Christopher Newport.[7]

On April 10, they entered the “Chesupioc” Bay and landed alongside “faire meddowes and goodly tall trees.”[8] Finally on April 26, 1607, the London Company reached Virginia, and declared their settlement Jamestown in honor of the King.[9] Almost immediately the London Company began sending shipments of trees back to England. A letter written in 1608 expressing the abundant discovery of good trees for export read, “I heare not of any novelties or other commodities she hath brought more then sweet woode.” However, exportation of any scale was delayed. During the winter of 1609, 154 of the original 214 colonists perished. The event would be remembered as the Starving Time, and it would be another eleven years before timber production of any consequence would resume in New England.[10]

In 1621 pressure from Plymouth Company's financiers impelled the colonists to ship to England a load of their commodities upon the vessel Fortune “laden with good clapboard as full as she could stowe.” However, it wasn't long before the pilgrims realized that their wood supply was too precious a resource to export, and promptly restricted overseas sales in a colony-wide decree:

“That for the preventing of such inconveniences as do and may befall the plantation by the want of timber, That no man of what condition soever sell or transport any manner of works…[that] may tend to the destruction of timber…without the consent approbation and liking of the Governor and councile.”[11]

By the 1680s, over two dozen sawmills were operating in southern Maine.[12]

Early housing

Homes serve as a stabilizer for settlements attempting to establish permanent residence.[13] Therefore, upon the establishment of Jamestown, the London Company quickly set about constructing a fortification for protection from hostile natives. By mid-June 1607 the company had finished constructing its fort, triangular in shape, enclosing about one acre, with its river side extending 420 feet and its other sides measuring 300 feet. Within the fort the company built a church, storehouse, living quarters - all the amenities the colony would need to survive. Between February and May 1609, improvements were made to the colony; twenty cabins were built, and by 1614 Jamestown consisted of, “two faire rowes of howses, all of framed timber, two stories, and an upper garret or corne loft high, besides three large, and substantial storehowses joined together in length some hundred and twenty foot, and in breadth forty….” Without the town”...in the Island [were] some very pleasant, and beautiful howses, two blockhowses...and certain other framed howses.”[14]

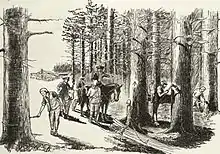

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Patuxet Indians had been shaping the forests for thousands of years. Where natural clearings already didn’t exist, the Patuxet systematically burned and felled tracts of forest for growing corn and constructing their dwellings. Many of the original colonial settlements would later be located on such sites, including Plymouth, Boston, Salem, Medford, and Watertown.[15] However, by the mid-1630s the original treeless outcroppings became overpopulated and could no longer support additional settlement. As a wave of new immigration arrived, settlers were forced into the woods to make their property claims.

One colonist explained the process of constructing a rudimentary shelter, whereby an individual would, “dig a square pit in the ground, cellar fashion, 6 or 7 feet deep, as long and as broad as they think proper, case the earth inside with wood all around the wall, and line the wood with the bark of trees or something else to prevent the caving in of the earth; floor this cellar with plank and wainscot it overhead for a ceiling, raise a roof of spars clear up and cover the spars with bark and green sods."[16]

As commodities, tools and building supplies steadily flowed into Virginia, home construction advanced, producing sturdy foundations upon which hewn timbers were erected, the exterior covered with clapboard, and the interior coated with wainscoting. By 1612, clay was being dredged from the James and Chickahominy Rivers. Bricks were fired and constructed into chimneys, as well as homes for the more affluent. However, necessity required clearing the land of timber resulting in an abundance of optimal material for building wood frame houses.

Regarding the architecture of the typical seventeenth century home, the structures were on average one-story structures with a loft accessible via a ladder-like stairway. There were often chimneys at both ends of the home, where meals typically were prepared upon an open hearth. The houses averaged between thirty and forty feet in length, and between eighteen and twenty feet in width.[17][18]

Commercial markets

In the 1600s virtually no commercial trade existed between Britain and New England. In fact, it would take nearly fifty years for the Admiralty to personally send mast ships and recruit colonials willing to produce timber for British stores. However, wood became a material used in abundance for everyday items. Hickory, ash, and hornbeam were used to craft bowls and tools. Cedar and black walnut were used for their ornate properties and crafted into decorative boxes, furniture and ceremonial gunstocks. And sweet sap was extracted from maple, rivaling honey as the colony's premier source of sweetener.[19][20]

Britain's Navigation Acts prevented New England from trading its valuable commodities with other European nations. However, timber was excluded from the Navigation Acts allowing the colonies to export vast quantities of wood commodities to nations otherwise beholden to British duties. Oak staves for wine barrels, along with building timber, white pine boards, and cedars shingles were traded to Spain, Portugal, the Canary Islands, the Azores, and Madeira. In addition, inter-colonial trade was unrestricted, allowing for the development of a major trade relationship with British Barbados.

Having long since dropped all other crops in favor of sugar production, and thoroughly stripped their islands of timber, Barbados and later other Caribbean islands became virtually dependent upon timber imports from New England. A letter from Barbadian representatives to the British Parliament in 1673 illustrated the necessity to which they relied upon New England timber. Lumber was required to maintain their buildings, staves and heading of porous red oak were in need for transporting sugar and molasses casks - even production resources were in demand to ensure economies of scale. By 1652 New England had established robust overseas markets shipping lumber, seafaring vessels, and fishing goods.[21][22]

Maritime markets

On April 27, 1607, one day after the London Company reached the Chesapeake, a group of colonists built a small boat and launched it the following day.[23] By the 1600s, nearly all commerce was waterborne, and in Virginia the shallop was the most popular boat for use in the colony. Due to its relatively small size (16–20 feet in length) it was perfectly suited for exploring rivers and creeks, as well as for trading and transporting tobacco to ships.[24][25]

Shortly after its inception, shipbuilding in the Virginia colony was a very simple operation carried out by plantation owners. A suitable location along the bank of a stream with water deep enough to float a vessel was essential. Likewise, access to suitable timber and the means to transport the materials were crucial. However, boatbuilding stagnated and shipbuilding failed to develop in those early years. Furthermore, the few boatwrights inhabiting the colony perished in the great Indian massacre of 1622.[26][27]

By 1629 the respective companies’ financiers had become increasingly concerned upon failures to realize returns on their investment. As a result, the New England Company (a reorganized version of the Plymouth Company) along with the directors of the Massachusetts Company sent their own shipwrights to jump-start domestic shipbuilding. Accordingly, shipbuilding in the early 1630s suddenly came to life along the banks of Boston and Charlestown. The region appeared as though it were designed for building ships.

White oaks provided excellent ship timber and planking. Cedars, chestnuts, and black oaks were perfect for the underwater portion of the ships – due to their impermeability to liquids, shock resistance, strength, natural durability, and decay-resistant properties among others.[19][28][29] Within a decade boats and ships proliferated.

In A Perfect Description of Virginia, an unnamed author wrote that the colony was swarming with “pinnaces, barks, great and small boats many hundreds, for most of their plantations stand upon the rivers’ sides and up little creeks and but a small way into the land.”[30] In 1662 the General Assembly of Virginia sought further to encourage shipbuilding by enacting a series of incentivizing laws which declared:

“Be it enacted that every one that shall build a small vessel with a deck be allowed, if above twenty and under fifty tons, fifty pounds of tobacco per ton; if above fifty and under one hundred tons, two hundred pounds of tobacco per ton; if above one hundred tons, two hundred pounds per ton. Provided the vessel is not sold except to an inhabitant of this country in three years.”

Builders were also incentivized by receiving two shilling exemptions off export duties per hogshead of tobacco, as well as exemption from castle duties, two pence reduction per gallon on imported liquor, and exemption from duties traditionally imposed on shipmasters upon entering and clearing. Furthermore, throughout the duration of the royal government there would be various laws remitting the duties on imports received on native ships, remission of tonnage duties, and exemptions for licensing and bond where applicable.[31]

The size of vessels in Virginia had steadily been increasing as well, and the craftsmanship had been improving, such that in a letter to Lord Arlington, Secretary of the Colony Thomas Ludwell boasted: “We have built several vessels to trade with our neighbors, and do hope ere long to build bigger ships and such as may trade with England.” Such was the astonishment at how quickly New England's shipbuilding had rapidly progressed that an article was submitted in the English News Letter of March 12, 1666 describing “A frigate of between thirty and forty [tons?], built in Virginia, looks so fair, it is believed that in short time, they will get the art of shipbuilding as good frigates as there are in England”.[32] As early as 1690 Dr. Lyon G. Tyler in The Cradle of the Republic wrote that ships of 300 tons were built in Virginia and trade in the West Indies was conducted in small sloops.[33]

Regardless of the increase in timber production, the commodity was not as profitable as Richard Hakluyt had hoped. The cause was due in part to the higher wages paid by freeholders compared to their serf counterparts in Europe, as well as the cost of transatlantic shipping. While Boston ports charged forty to fifty shillings, the Baltic ports only charged nine.[34]

That changed when England awoke to a timber crisis after commercial competition with the Dutch came to a breaking point. The Navigation Acts of 1651 had greatly limited imports into England, prompting Denmark to prey upon British ships as they sailed to and from the Baltic Sea transporting their timber cargo. It was at this time, on the eve of the first Anglo-Dutch War (1652–1654) that the Admiralty considered a plan to develop a North American source of timber and masts, and forgo possible crisis as a result of impending lengthy repair of battle-shattered masts.[26]

North European fir had been the Admiralty's timber of choice for its mast construction. However, finding its supply chain obstructed, the Admiralty's second choice was the North American white pine. A shipload had been received from Jamestown in 1609 and another in 1634 from Penobscot Bay, both of which were found to be agreeable .[35] There is disagreement amongst scholars about which variety was the strongest, however the North American white pine was considered more resilient, one fourth lighter in weight, and exponentially larger; reaching a height of 250 feet, several feet in diameter at the base, and weighing in as much as 15 to 20 tons.[36] Accordingly, the Admiralty sent a fleet of mast ships in 1652 and thus began Britain's steady importation New England masts .[19]

Following the development of New England's shipbuilding industry, it became common for the British to retail New England ships due to significantly lower production costs. The abundance of naval stores and good timber enabled colonists to produce ships thirty percent cheaper than the English, making it the most profitable manufactured export during the colonial period.[37]

The Admiralty's venture to get mast logs out of the New England forest, in turn, produced a labor force that with it developed into a booming domestic lumber industry. Since ninety-plus percent of New England pines harvested were unsuitable for masts, an important building and commodities lumber market emerged converting rejected masts into merchantable boards, joists and other structural lumber. Such was the success of the colonial entrepreneurs that the Crown became concerned that its newfound resource of dependable naval stores and masts would quickly dwindle.

In response, King William III enacted a new charter in October 1691 governing the Massachusetts Bay Colony, reserving for the King “all Trees of the Diameter of Twenty Four Inches and upwards” that were not previously granted to private persons.[38][39] The portion of the charter quickly became known as the King's Broad Arrow. All timber consigned under the charter were marked with three strikes of an ax resembling an upside down arrow. The importance of the policy only increased with the onset of The Great Northern War (1700–1721), which all but halted Baltic exports to England. Consequently, British Parliament began passing a series of acts regulating imports from the Baltic and promoting imports from New England.[40]

The Act of 1704 encouraged the import of naval stores form New England, offering £4 per ton of tar or pitch, £3 per ton of resin of turpentine, and £1 per ton of masts and bowsprits (40 cubic feet). The Act of 1705 forbade the cutting of unfenced or small pitch pine and tar trees with a diameter less than twelve inches. The Act of 1711 gave the Survey General of the King's Forests authority over all colonies from New Jersey to Maine. Lastly, the Act of 1721 extended dominion of the King's Forests to any trees not found within a township or its boundaries, and officially recognized the American word ‘lumber’ for the first time.[40]

However, the acts and policy proved virtually impossible to enforce. A survey in 1700 documented more than fifteen thousand logs that violated the twenty-four inch restriction.[40] Attempts to curb illegal lumbering continued under the appointment of John Bridger as survey general in 1705. His task was to survey and protect His Majesty's Woods, duties of which he performed with great enthusiasm. Bridger conducted extensive mast surveys, confiscated illegal timber, and prosecuted violators, to no avail. Colonists didn't care, and often disregarded the Broad Arrow mark. It became virtually impossible for a single surveyor with a few deputies to police the entire expanse of New England's forests. After much pleading on behalf of Bridger for more resources and authority, the Parliamentary Acts (1704–1729) slowly eased the burden of his charge. Ironically, in 1718 Bridger was removed for corruption and his predecessor Colonel David Dunbar, treated the post with indifference.[41][42]

The effects of the policy on the American economy remains unclear. Without the Admiralty's quest for choice timber the American lumber industry may not have developed as quickly. Certainly, the policy ensured a steady reliable source of mast timber during England's ascension to naval dominance, but at a price. Perceived violations of property rights on New England colonists served only to stoke the embers of rebellion. Shipments of New England timber continued unabated until the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. The last supply of New England masts reached the home country on July 31, 1775 after more than 4500 white pines had been sent under the Broad Arrow policy.[43][44]

The American industrial revolution caused the national demand for timber to spike. Prior to the Civil War, more than ninety percent of the nation's energy came from wood, fueling the great transportation vehicles of the era.[12] As Americans settled the timber-starved Great Plains, they needed material from the lumber-rich parts of the nation with which to build their cities. The burgeoning railroad industry accounted for a fourth of the national lumber demand and required the product to build rail cars and stations, fashion ties, and power trains.[12] Even as the coal began to replace wood as an energy source, the coal mining industry itself needed lumber to support its mining structures and create its own rail beds. Technological development helped the industry meet the soaring demand. New methods of transporting lumber, like the steam engine, provided the means to log further inland and away from water. New machines such as the circular saw and the band saw allowed forests to be felled with significantly improved efficiency.[45] The resulting increased timber production saw New England forests become rapidly depleted, and American loggers began methodically cutting their way south and west in search of new forests.

Nineteenth century

| United States Lumber Production [46] | |

|---|---|

| Year | Annual Production (millions of board feet) |

| 1850 | 5,000 |

| 1860 | 8,000 |

| 1870 | 13,000 |

| 1880 | 18,000 |

| 1890 | 23,500 |

| 1900 | 35,000 |

By the 1790s, New England was exporting 36 million feet of pine boards and 300 ship masts annually, with over 75 percent coming from Massachusetts (which included Maine) and another 20 percent coming from New Hampshire.[2] By 1830, Bangor, Maine had become the world's largest lumber shipping port and would move over 8.7 billion board feet of timber over the following sixty years.[3] Throughout the 19th century, Americans headed west in search of new land and natural resources. The timber supply in the Midwest was dwindling, forcing loggers to seek new sources of “green gold.” In the early decades of the 19th century, the Great Lakes and their tributary waterways flowed through areas densely covered with virgin timber. The timber became a primary resource for both regional and national building materials, industry, and fuel.[47][48][49]

By 1840, upstate New York and Pennsylvania formed the seat of the industry. By 1880 the Great Lakes region dominated logging, with Michigan producing more lumber than any other state.[12]

Twentieth century

By 1900, with timber supplies in the upper Midwest already dwindling, American loggers looked further west to the Pacific Northwest. The shift west was sudden and precipitous: in 1899, Idaho produced 65 million board feet of lumber; in 1910, it produced 745 million.[50] By 1920, the Pacific Northwest was producing 30 percent of the nation's lumber.[51]

Whereas previously individuals or families were managing single sawmills and selling the lumber to wholesalers, towards the end of the nineteenth century this industry structure began to give way to large industrialists who owned multiple mills and purchased their own timberlands.[12] None was bigger than Frederick Weyerhauser and his company, which started in 1860 in Rock Island, Illinois and expanded to Washington and Oregon. By the time he died in 1914, his company owned over 2 million acres of pine forest.[52]

Following the onset of the Great Depression, many companies were forced to shut down. Total production of lumber fell at a devastating rate, from 35 billion board feet in 1920 to 10 billion board feet in 1932. Moreover, the steady decline of gross income, net profits, and increased consumption of cement and steel products, exacerbated the decline of lumber production.[53]

| United States Gross Income, Net Profits, Production, and price index in the Lumber Industry 1920 -1934[54] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Gross Income (In Millions Dollar) |

Net Profit (In Millions Dollar) |

Production (In Board feet) (In Millions) |

Wholesale Price Index (1926=100) |

| 1920 | 3,312 | N/A | 35,000 | N/A |

| 1922 | 2,402 | 167 | 35,250 | N/A |

| 1924 | 2,835 | 132 | 39,500 | 99.3 |

| 1926 | 3,069 | 117 | 39,750 | 100.0 |

| 1928 | 2,342 | 82 | 36,750 | 90.5 |

| 1930 | 1,988 | 110 | 26,100 | 85.8 |

| 1932 | 854 | 202 | 10,100 | 58.5 |

| 1934 | N/A | N/A | 12,827 | 84.5 |

In 1933, following the election and first term of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) was passed. President Roosevelt believed that unrestrained competition was one of the root causes of the Great Depression. According to The Effect of the N.R.A. Lumber Code on Forest Policy, national lumber codes regulated various aspects of the industry, including wages, hours, and price.[55]

The industry was suffering on many fronts. It was incurring low prices for its products, low wages for its workers, and facing exhausted tracts of forest caused previously by overproduction in the late 1920s.[55] As illustrated in table 2, prices rebounded in 1934. Note that it is not only because of Lumber code but also comprehensive impact of devaluation, amplified public work spending, and improved banking system.[56]

As old-growth forest disappeared rapidly, the United States' timber resources ceased to appear limitless. Canadian lumberman James Little remarked in 1876 that the rate at which the Great Lakes forests were being logged was "not only burning the candle at both ends, but cutting it in two, and setting the match to the four ends to enable them to double the process of exhaustion."[57]

To deal with the increasingly limited availability of timber resources, the Division of Forestry was established in 1885, and in 1891 the Forest Reserve Act passed, setting aside large tracts of forest as federal land. Loggers were forced to make already cut lands productive again, and the reforesting of timberlands became integral to the industry. Some loggers pushed further northwest to Alaskan forests, but by the 1960s most of the remaining uncut forest became protected.[12]

The portable chain saw and other technological developments helped drive more efficient logging, but the proliferation of other building materials in the twentieth century saw the end of the rapidly rising demand of the previous century. In 1950, the United States produced 38 billion board feet of lumber, and that number remained fairly constant throughout the decades moving forward, with the national production at 32.9 billion board feet in 1960 and 34.7 billion board feet in 1970.[58]

Twenty-first century

Presently there is a healthy lumber economy in the United States, directly employing about 500,000 people in three industries: Logging, Sawmill, and Panel.[59] Annual production in the U.S. is more than 30 billion board feet making the U.S. the largest producer and consumer of lumber.[59] Despite advances in technology and safety awareness, the lumber industry remains one of the most hazardous industries in the world.

While challenges in today's market exist, the United States remains the second largest exporter of wood in the world. Its primary markets are Japan, Mexico, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Due to higher labor costs in the United States, it is common practice for raw materials to be exported, converted into finished goods and imported back into the United States.[59] For this reason, more raw goods including logs and pulpwood chip are exported than imported in the United States, while finished goods like lumber, plywood and veneer, and panel products have higher imports than exports in the U.S.[60]

Recently there has been a resurgence in logging towns in the United States. This has been due in large part to the housing recovery.[61]

Notes

- Manning 1979, p. 7

- Defebaugh, James E. History of The Lumber Industry of America. Vol. 2. Chicago: American Lumberman, 1907. 17.

- "Nineteenth Century Industries: Lumber." Penobscot Marine Museum. http://penobscotmarinemuseum.org/pbho-1/working-the-bay/nineteenth-century-industries-lumber.

- Rutkow 2012, p. 14

- Rutkow 2012, pp. 11-15

- Billings 1975, p. 3

- Billings 1975 p. 5

- Jester 1957, p. 2

- Rutkow 2012, pp 17-18

- Rutkow 2012, pp 18-19

- Rutkow 2012, pp 21-22

- "Lumber Industry." Encyclopedia of American History. Answers Corporation, 2006.

- Jester 1957, p. 1

- Hatch 1957, pp 4, 8, 13

- Rutkow 2012, p. 20

- Rutkow 2012, p22

- Jester 1957, pp. 20-21, 24

- Stanard 1970, p.60

- Manning 1979, p. 17

- Rutkow 2012, pp. 22-23

- Rutkow 2012, pp 24-25

- Manning 1979, p. 22

- Hudson 1957, p. 1

- Evans 1957, p. 21

- Manning 1979, p. 5

- Manning 1979, p. 13

- Evans 1957, p. 16

- Panshin & De Zeeuw 1970, pp. 572, 576

- Rutkow 2012, p. 23

- Evans 1957, p. 12

- Evans 1957, p. 23

- Evans 1957, pp. 24, 25

- Evans 1957, p. 26

- Rutkow 2012, p 24

- Manning 1979, p. 9

- Rutkow 2012, p. 27, 28

- Rutkow 2012, pp. 23, 24

- Rutkow 2012, pp. 25, 27

- Manning 1979, p. 25

- Manning 1979, p. 28

- Manning 1979, p. 33

- Rutkow 2012, p. 29

- Manning 1979, pp. 13, 33

- Rutkow 2012, p. 32

- "Lumber Industry," Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia 2000 http://encarta.msn.com Archived 2009-10-31 at WebCite © 1997-2000 Microsoft Corporation

- United States Forest Service. The Lumber Cut of the United States 1907. Government Printing Office, 1908. p. 7.

- http://mshistorynow.mdah.state.ms.us/articles/171/growth-of-the-lumber-industry-1840-to-1930

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-12-24. Retrieved 2013-12-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://thunderbay.noaa.gov/history/lumber.html

- Pacific Northwest Research Station. Status of the interior Columbia basin: Summary of scientific findings (General Technical Report PNW-GTR-385). Portland, OR: USDA Forest Service, (1996, November). p. 55.

- Marchak, M. P. Logging the globe. Montreal & Kingston, Jamaica: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1995. p. 56.

- Faiman-Silva, Sandra L. Choctaws at the Crossroads: The Political Economy of Class and Culture in the Oklahoma Timber Region. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2000. p 100.

- Simpson and Swan 1937 pp. 110-111

- Simpson and Swan 1937 p. 111

- Duncan 1941, p. 92

- Duncan 1941, p. 94

- Little, James. The Timber Supply Question, of the Dominion of Canada and the United States of America. Montreal: Lovell, 1876. p. 14.

- Ulrich, Alice H. U.S. Timber Production, Trade, Consumption, and Price Statistics, 1950-80. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1981. p 46.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-12-21. Retrieved 2013-12-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/fplrp/fpl_rp676.pdf p. 33

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323864304578316132672998200

References

- Billings, W. M. (1975). The Old Dominion in the seventeenth century: A documentary history of Virginia, 1606–1689. Chapel Hill: Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture at Williamsburg, Va., by the University of North Carolina Press.

- Evans, C. W. (1957). Some Notes on Shipbuilding and Shipping in Colonial Virginia. Williamsburg: Virginia 350th Anniversary Celebration Corp.

- Duncan, Julian (1941). The Effect of the N.R.A. Lumber Code On Forest Policy: Vol. 49, No. 1 JSTOR 1824348

- Hatch, C. E. (1957). The First Seventeen Years, Virginia, 1607–1624. Williamsburg: s.n.

- Hudson, J. P., & Virginia 350th Anniversary Celebration Corporation (1957). A pictorial booklet on early Jamestown commodities and industries. Williamsburg, Va: Virginia 350th Anniversary Celebration Corp.

- Jester, A. L. (1957). Domestic Life in Virginia in the Seventeenth Century. Williamsburg: Virginia 350th Anniversary Celebration Corp.

- Manning, S. F. (1979). New England masts and the King's Broad Arrow. Greenwich, London: Trustees of the National Maritime Museum.

- Mason, H. (2008). The Shallop | Captain John Smith Historical Trail. Retrieved December 17, 2013, from http://www.smithtrail.net/captain-john-smith/the-shallop/

- Panshin, A. J., & De, Z. C. (1970). Textbook of wood technology: Vol. 1. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Rutkow, E. (2012). American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation. New York: Scribner.

- Simpson, J.P. and Swan, Edmund L.C. (1937) Improvements in the Lumber Industry: vol. 193 no. 1 110–119, from http://ann.sagepub.com/content/193/1/110

- Stanard, M. N. (1970). Colonial Virginia: Its people and customs. Detroit: Singing Tree Press.

- Washburn, W. E. (1957). Virginia under Charles I and Cromwell, 1625–1660.

- Williamsburg: Virginia 350th Anniversary Celebration Corp.