Hurricane Leslie (2018)

Hurricane Leslie (known as Storm Leslie or Cyclone Leslie in Portugal and Spain while extratropical) was the strongest cyclone of tropical origin to strike the Iberian Peninsula since 1842. A large, long-lived, and very erratic tropical cyclone, Leslie was the twelfth named storm and sixth hurricane of the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season. The storm had a non-tropical origin, developing from an extratropical cyclone that situated over the northern Atlantic on 22 September. The low quickly acquired subtropical characteristics and was classified as Subtropical Storm Leslie on the following day. The cyclone meandered over the northern Atlantic and gradually weakened, before merging with a frontal system on 25 September, which later intensified into a powerful hurricane-force extratropical low over the northern Atlantic.

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

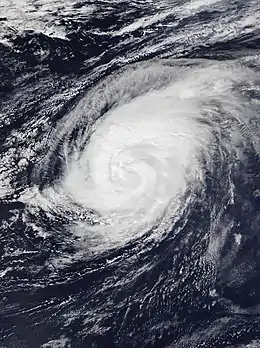

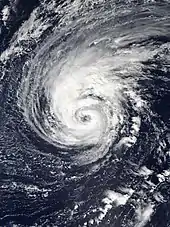

Hurricane Leslie near peak intensity southwest of the Azores on 11 October | |

| Formed | 23 September 2018 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | 16 October 2018 |

| (Extratropical after 13 October) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 90 mph (150 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 968 mbar (hPa); 28.59 inHg |

| Fatalities | 2 direct, 15 indirect |

| Damage | > $500 million (2018 USD) |

| Areas affected | Azores, Bermuda, East Coast of the United States, Madeira, Iberian Peninsula, France |

| Part of the 2018 Atlantic hurricane and 2018–19 European windstorm seasons | |

While Leslie began to weaken late on 27 September, the low began to re-acquire subtropical characteristics, and by 28 September, Leslie had completed the transition to a subtropical storm once again. Leslie became fully tropical and gradually intensified, becoming a Category 1 hurricane early on 3 October, and initially peaked with 1-minute sustained winds of 140 km/h (85 mph) later that day. Leslie gradually weakened, falling to tropical storm intensity late on 4 October. The cyclone continued to slowly weaken before beginning to re-intensify on 8 October. Two days later, Leslie reached hurricane status for the second time. Leslie continued to slowly strengthen, reaching peak intensity with sustained winds of 150 km/h (90 mph) and a minimum central pressure of 968 hPa (28.59 inHg), early on 12 October. Leslie then began to gradually weaken later that day, while accelerating towards the northeast and passed far south of the Azores. On 13 October, Leslie passed north of Madeira, before transiting to an extratropical cyclone just off the Portuguese coast later. Leslie's extratropical remnant made landfall in central Portugal a few hours later. The extratropical low continued moving northeastward while rapidly weakening, passing over the Bay of Biscay, before dissipating on 16 October over western France.

Hurricane Leslie prompted the issuance of tropical storm watches and warnings for Madeira Island, the first in its history.[1] The storm was also responsible for 16 deaths, including 2 in Portugal and 14 in France.[2][3] In November 2018, Aon estimated that Leslie's damage total exceeded US$500 million.[4]

Meteorological history

Origins and initial extratropical transition

On 19 September, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) began forecasting the development of a non-tropical low pressure system within the next several days far to the southwest of the Azores, with the possibility of the low gradually acquiring tropical or subtropical characteristics.[5] Three days later, an extratropical cyclone formed along a frontal boundary about 1,300 km (805 mi) south-southwest of the Azores,[6] which was associated with part of the remnants of Hurricane Florence.[7][8] The low then acquired gale-force winds as it meandered over the northern Atlantic.[9] On 23 September, the low lost its frontal features and the outer cloud bands became increasingly well-defined, and at 12:00 UTC, the NHC designated the system as Subtropical Storm Leslie.[6]

Leslie continued its erratic movement as the steering current remained weak.[6] The future development of Leslie was uncertain, due to the possibility of an approaching, larger low pressure system becoming dominant and absorbing Leslie, although some global forecast models maintained Leslie as the dominant system following the merger.[10] Late on 24 September, Leslie embedded in an area with dry air and moderate wind shear, causing its cloud pattern to become ragged and less organised,[11] and Leslie weakened to a subtropical depression early on 25 September.[6]

Twelve hours later, Leslie transited back to an extratropical low.[6] Microwave data showed that the system had a surface circulation elongated around an intruding baroclinic zone.[12] Late on 25 September, the NHC forecasted that Leslie would regain subtropical characteristics in a couple of days.[13] Soon afterward, Leslie merged with a frontal system and subsequently strengthened.[6] Early on 27 September, Leslie attained hurricane-force winds, likely due to baroclinic process.[14] Despite weakened to storm-force strength later that day, Leslie began to show some subtropical characteristics, and its shower activity gradually became organised.[15] On the next day, Leslie lost much of its baroclinic field, and its convection became more organised.[16] Therefore, the NHC once again classified Leslie as a subtropical storm and resumed issuing advisories at 12:00 UTC.[6]

Tropical transition, initial peak and subsequent weakening

Soon after being re-classified, Leslie moved to the due west under the interactions with the subtropical ridge to the west and a large deep-layer low that formed to the east.[16] On 29 September, the storm turned to the southwest as it embedded to the deep-layer low, and Leslie's deep convection became more concentrated near the center. This signified its transition into a tropical cyclone.[17] Later that day, Leslie developed an anti-cyclonic outflow to its northeast and southeast, and it developed a warm core structure.[18] At 18:00 UTC, Leslie became fully tropical, and it transited to a tropical storm about 1,850 km (1,150 mi) west-southwest of the Azores.[6]

On the next day, Leslie moved slowly to the southwest over the northern Atlantic due to two mid-level ridges, without much change in intensity.[19] Starting on 1 October, Leslie began to intensify, while the NHC noted an increase in convective banding in the north and northwest of Leslie.[20] Leslie continued to steadily intensify over the next days. On 3 October, Leslie developed a ragged eye,[21] and it intensified to a hurricane at 06:00 UTC.[6] At the same time, Leslie became stationary due to very weak steering current.[21] Twelve hours later, Leslie achieved its initial peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 140 km/h (85 mph) and a minimum central pressure of 970 hPa (28.64 inHg).[6] Later that day, Leslie began to accelerate northward, under the influence of a shortwave trough to the northwest and a mid-level ridge to the southeast.[22]

The hurricane began to weaken on 4 October as it moved over cooler waters.[23] Leslie weakened to a tropical storm at 18:00 UTC.[6] Its structure continued to degrade, with the NHC noted that the system lacked an inner wind core.[24] Late on 5 October, Leslie turned to the southeast, as it encountered the southern edge of a mid-latitude westerlies.[25] Despite moving over cool waters with just 24 °C (75 °F), Leslie maintained its intensity throughout 7 October.[26] Nonetheless, the storm bottomed out with winds of 85 km/h (50 mph) early on 8 October.[6]

Peak intensity, second extratropical transition and demise

Later that day, Leslie began to intensify again, as satellite images showed that the storm developed a small central dense overcast with the cloud pattern became more symmetric.[27] Meanwhile, Leslie turned to the south-southeast, as the storm was steered by a mid-level ridge.[28] Over the next day, Leslie continued to intensify under favourable environment. Microwave data revealed that the storm developed a small mid-level eye,[29] and Leslie re-attained hurricane status early on 10 October.[6] Leslie then turned southward, under the influence of a mid- to upper-level trough.[30] Later that day, Leslie turned sharply to east-northeast, due to a mid-latitude trough.[31] The hurricane continued its intensification trend as it moved over an area with low wind shear.[32] Leslie reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 150 km/h (90 mph) and a minimum central pressure of 968 hPa (28.59 inHg), early on 12 October, about 1,060 km (660 mi) south-southwest of the Azores.[6] At the same time, the small eye of the hurricane was apparent on satellite images.[33]

Leslie began to weaken later that day while accelerating to east-northeast, due to the combination of increasing wind shear and cooler waters.[34] At 06:00 UTC on 13 October, Leslie made its closest approach to Madeira Island, passing about 320 km (200 mi) north-northwest of the island.[6] Soon afterward, Leslie began its extratropical transition while continued racing east-northeastward, after fully embedded in the mid-latitude westerlies.[35] The weakening trend of the hurricane slowed down despite unfavourable environment, possibly because of baroclinic forcing.[36] At 18:00 UTC, Leslie dropped below hurricane strength and completely lost all the tropical characteristics simultaneously, at about 190 km (120 mi) west-northwest of Lisbon, Portugal.[37] Three hours later, the NHC issued the final advisory on Leslie as it approached the western Portuguese coast.[38] Leslie's extratropical remnant made landfall in Figueira da Foz at 21:10 UTC, causing damage throughout the central part of the country.[39][6] Afterward, Leslie's center became ill-defined while moving northeastward, over the Bay of Biscay.[6] The low reached western France by 15 October.[40][41] Early on 16 October, Leslie's remnant was absorbed into Hurricane Michael's extratropical remnant, which was situated to the west, following a brief Fujiwhara interaction.[42][43]

Preparations and impact

| Country | Deaths |

|---|---|

| Portugal | 2 |

| France | 15 |

| Total | 17 |

United States

From late September through early October, Leslie brought high surf to the East Coast of the United States, inducing the highest swell observed in some locations for years. Leslie also generated the single-longest period of tropical swells observed in the Outer Banks in the last 20 years, producing surf at chest-height or higher. The highest surf was observed on 26–28 September, when Leslie was a powerful extratropical cyclone with hurricane-force winds.[44]

Portugal

Late on 11 October, the Government of Portugal issued a tropical storm watch for Madeira Island,[45] which was changed to a tropical storm warning six hours later.[46] It was the first known tropical storm warning issued for that island in recorded history.[1] Madeira officials closed beaches and parks.[47] The threat of the storm caused eight airlines to cancel flights into Madeira. More than 180 sports matches on the island were canceled, more than half of which affecting the Madeira Football Association.[48] The warnings were discontinued on 13 October as Leslie moved away from the islands.[49]

In advance of Leslie, IPMA issued red warnings for high winds or dangerous coastal conditions for 13 out of its 18 districts, including the capital Lisbon.[50] Several events were canceled or postponed, including the Revenge of the 90s party scheduled for the night of 13 October in Lisbon being postponed to the 20th. A Mafalda Veiga concert in Campo Pequeno, the play "Baixa Terapia" at the Tivoli BBVA, and the evening session of the French Film Festival were also canceled.[51] In addition, the final match of the Rink Hockey Female European Championship, played on 14 October in Mealhada, was suspended with less than two minutes left.[52]

At 21:10 UTC on 13 October, Leslie made landfall in Figueira da Foz as a storm-force extratropical cyclone with winds of 110 km/h (70 mph). It was the first cyclone of tropical origin to hit the Iberian Peninsula since Vince in 2005, and the strongest cyclone to hit the peninsula since 1842. Winds up to 175 km/h (109 mph) were recorded in Figueira da Foz, which has been attributed to a sting jet.[53] Heavy rains and strong waves affected the entire country, leaving 324,000 homes without power, more than 60 people needed to be evacuated. At least 1,000 trees were uprooted in the coastal areas.[54] The storm caused 2 deaths, and slightly injured 28 others.[2] Estimated damage nationwide by Aon exceeded €100 million (US$115.5 million), including an insurance loss of €60 million (US$69.3 million).[55]

Spain

Winds of up to 96 km/h (60 mph) were reported near Zamora. Villardeciervos also recorded winds of 87 km/h (54 mph); strong winds caused trees to be uprooted. AEMET issued the yellow level warnings due to the risk of storms related to Leslie, advising citizens to beware objects that may fall on public roads. There are no reports of fatalities due to Leslie in Spain.[56]

France

The moisture of Leslie's dissipating extratropical remnant fed a quasi-stationary cold front over southwestern France, generating heavy thunderstorms and leading to flash flooding in that area.[57] Carcassonne received 160–180 mm (6.3–7.1 in) of rainfall within five hours; water level in the city rose 8 m (26 ft) during that period. 15 people died because of the flash flood, mainly in the town of Villegailhenc, Aude.[58] This was partially due to the fact that the Aude River rose to a height of 7 m (23 ft), its highest level since 1891.[3] Wind gusts of 111 km/h (69 mph) and wave heights of 7.8 m (26 ft) were recorded in Sète.[59] Damage in Aude were calculated at €220 million (US$254 million).[60]

See also

- List of Azores hurricanes

- Tropical cyclone effects in Europe

- Hurricane Ginger (1971), longest-lasting and static Atlantic hurricane

- Hurricane Vince (2005), made landfall in Spain as a tropical depression

- Hurricane Nadine (2012), long-lived and an erratic hurricane of similar intensity

- Hurricane Ophelia (2017), easternmost Atlantic major hurricane on record\

- Subtropical Storm Alpha (2020), a system that would make landfall in Portugal, in 2020.

References

- Eric S. Blake (12 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Discussion Number 63 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "Leslie. 28 feridos e mais de duas mil ocorrências. O que se sabe até agora" (in Portuguese). SAPO 24. 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- "France: le bilan des inondations dans l'Aude monte à 14 morts" (in French). Le Soir. 17 October 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- Global Catastrophe Recap October 2018 (PDF). AON (Report). AON Benfield. 7 November 2018. p. 6. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- David Zelinsky (21 September 2018). NHC Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook Archive (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Pasch, Richard J.; Roberts, David P. (29 March 2019). Hurricane Leslie (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Jeff Masters (19 September 2018). "After Florence: What's Next in the Atlantic?". Weather Underground. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Michael J. Brennan (22 September 2018). NHC Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook Archive (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- Berg, Robbie (23 September 2018). Tropical Weather Outlook. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Avila, Lixion A. (23 September 2018). Subtropical Storm Leslie Discussion Number 3. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Berg, Robbie (24 September 2018). Subtropical Storm Leslie Discussion Number 6. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Roberts, Dave (25 September 2018). Post-Tropical Cyclone Leslie Discussion Number 9. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Pasch, Richard (25 September 2018). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Berg, Robbie (27 September 2018). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Beven, Jack (27 September 2018). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Beven, Jack (28 September 2018). Subtropical Storm Leslie Discussion Number 10. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Avila, Lixion A. (29 September 2018). Subtropical Storm Leslie Discussion Number 12. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Zelinsky, David (29 September 2018). Tropical Storm Leslie Discussion Number 14. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Brown, Dabiel (30 September 2018). Tropical Storm Leslie Discussion Number 16. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Brown, Dabiel (1 October 2018). Tropical Storm Leslie Discussion Number 20. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Brown, Dabiel (3 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Discussion Number 28. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Cangialosi, John; Onderlinde, Matthew (3 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Discussion Number 30. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Beven, Jack (4 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Discussion Number 33. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Avila, Lixion A. (5 October 2018). Tropical Storm Leslie Discussion Number 35. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Beven, Jack (5 October 2018). Tropical Storm Leslie Discussion Number 38. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Zelinsky, David (7 October 2018). Tropical Storm Leslie Discussion Number 45. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Blake, Eric (8 October 2018). Tropical Storm Leslie Advisory Number 50. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Blake, Eric (9 October 2018). Tropical Storm Leslie Advisory Number 51. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Zelinsky, David (9 October 2018). Tropical Storm Leslie Advisory Number 54. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Cangialosi, John (10 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Discussion Number 56. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Zelinsky, David (10 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Discussion Number 58. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Zelinsky, David (11 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Discussion Number 60. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Blake, Eric (12 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Advisory Number 63. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Brown, Daniel (12 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Advisory Number 66. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Beven, Jack (13 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Advisory Number 68. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Beven, Jack (13 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Advisory Number 67. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Avila, Lixion A. (13 October 2018). Post-Tropical Cyclone Leslie Tropical Cyclone Update. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Stewart, Stacy R. (13 October 2018). Post-Tropical Cyclone Leslie Advisory Number 70. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Branco, Carolina (14 October 2018). ""É uma catástrofe absolutamente inédita". O rasto da tempestade entrou pela Figueira da Foz" (in Portuguese). Observador. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Europe Weather Analysis on 2018-10-14". Free University of Berlin. 14 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- "Europe Weather Analysis on 2018-10-15". Free University of Berlin. 15 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Daniel Chaitin (16 October 2018). "When Michael met Leslie: Ex-hurricanes dance, merge over Spain". Washington Examiner. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- "Europe Weather Analysis on 2018-10-16". Free University of Berlin. 15 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Matt Pruett (10 October 2018). "Hurricane Leslie Wasn't Perfect..." Surfline. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- David Zelinsky (11 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Advisory Number 62 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Eric S. Blake (12 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Advisory Number 63 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "Arquipélago da Madeira em "alerta máximo" devido ao furacão Leslie" (in Portuguese). Diário de Notícias. 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "Furacão Leslie: mais de 180 jogos cancelados na Madeira e duas exceções nas modalidades" (in Portuguese). O Jogo. 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Lixion A. Avila (13 October 2018). Hurricane Leslie Intermediate Advisory Number 68A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- "Storm Leslie: Portugal hit by 110mph winds as thousands of homes lose power". Sky News. 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Lusa, Carolina Branco, Rita Cipriano, Agência. "Furacão Leslie. A major tempestade desde 1842". Observador (in Portuguese). Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "The assignation of the title of Female European Championship is suspended". World Skate Europe. 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "STING JET ASSOCIADO AO LESLIE". www.ipma.pt (in Portuguese). 14 October 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "'Zombie' storm Leslie smashes into Portugal". Agence France-Presse. 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Prejuízos do furacão Leslie devem ultrapassar os 100 milhões de euros". Correio da Manhã (in Portuguese). Lusa. 26 October 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Tropical storm Leslie arrives in Zamora with gusts of wind over 96 km / h". International News. 14 October 2018. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Épisode pluvio-orageux exceptionnel dans l'Aude le 15 octobre". www.keraunos.org (in French). Keraunos. 15 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018..

- "Inondations dans l'Aude : deux semaines après le drame, le bilan s'alourdit à 15 morts". Actu.fr (in French). 30 October 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018..

- CASTAN Patrice (15 October 2018). "Sète : des rafales de vent à 111 km/" (in French). MidiLibre. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Inondations dans l'Aude : le coût final est estimé à 220 millions d'euros" (in French). Le Monde. 9 November 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Leslie (2018). |

- The National Hurricane Center's advisory archive on Hurricane Leslie