Meteorological history of Hurricane Florence

The meteorological history of Hurricane Florence spanned 22 days from its inception on August 28, 2018, to its dissipation on September 18. Originating from a tropical wave over West Africa, Florence quickly organized upon its emergence over the Atlantic Ocean. Favorable atmospheric conditions enabled it to develop into a tropical depression on August 31 just south of the Cape Verde islands. Intensifying to a tropical storm the following day, Florence embarked on a west-northwest to northwest trajectory over open ocean. Initially being inhibited by increased wind shear and dry air, the small cyclone took advantage of a small area of low shear and warm waters. After achieving hurricane strength early on September 4, Florence underwent an unexpected period of rapid deepening through September 5, culminating with it becoming a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale. Thereafter, conditions again became unfavorable and the hurricane quickly diminished to a tropical storm on September 7.

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Map plotting the track and the intensity of the storm, according to the Saffir–Simpson scale | |

| Formed | August 31, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 18, 2018 |

| (Extratropical after September 17) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 150 mph (240 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 937 mbar (hPa); 27.67 inHg |

| Areas affected |

|

| Part of the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season | |

From September 7–9, Florence's forward momentum slowed as it turned west. Favorable conditions again fostered intensification on September 9 and the system regained hurricane status. Turning northwest toward the United States, a second phase of rapid intensification ensued that day into September 10 with Florence regaining Category 4 strength. It subsequently reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a pressure of 937 mbar (hPa; 27.67 inHg). Steady weakening occurred over the following days as steering currents began to collapse. The hurricane slowed to a crawl by September 13 as it approached North Carolina. Torrential rains began affecting the state on this day and persisted through September 17.

Florence made landfall near Wrightsville Beach on September 14 with winds of 90 mph (150 km/h). With the system remaining close to the coastline it weakened slowly, eventually degrading to a tropical depression on September 16. Training rainbands produced prolific, record-breaking rainfall across North and South Carolina throughout this period. Catastrophic flooding and extensive wind damage ensued, resulting in 22 direct fatalities and 30 indirect deaths across the Carolinas and Virginia.[1] Florence later transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 17 before dissipating the following day.

Origins

On August 28, 2018, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) began monitoring a tropical wave—an elongated area of low air pressure—over West Africa for possible tropical cyclogenesis over the subsequent five days as it progressed west.[2] Development into a tropical cyclone became increasingly likely the following day;[3] and a more defined low coalesced along the coast of Senegal on August 30.[4] On this day, the system split in two, with the northern one ultimately developing into Florence and the southern portion later becoming Tropical Depression Nineteen-E in the Eastern Pacific.[1] Favorable environmental conditions, including ample moisture and low wind shear,[5] enabled further organization and development of broad shower and thunderstorm activity. Lacking a well-defined center but posing an immediate threat to Cape Verde, the NHC began issuing advisories on the system as Potential Tropical Cyclone Six later that day.[nb 1] Easterly trade winds propelled the disturbance along a west to west-northwest trajectory.[8] Through much of the day and into August 31, convection remained confined to the southwest of the disturbance within a monsoon trough and precluded its classification as a tropical cyclone.[9] Toward the end of August 31, convective organization became sufficient for the NHC to mark the formation of Tropical Depression Six as the system passed south of Santiago in Cape Verde.[10]

By September 1, the primary steering factor shifted to a strong, expansive subtropical ridge anchored well to the north. This ridge extended from Europe to the eastern United States and remained the dominant steering factor through much of the storm's history.[1] Moderate wind shear temporarily stunted development and displaced convection to the eastern side of the depression.[11] Pronounced banding features surrounded the circulation and the depression intensified to a tropical storm; accordingly the NHC assigned the system the name Florence.[12] Satellite intensity estimates indicated Florence achieved maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) by 09:00 UTC on September 2.[13] Thereafter, shear and entrainment of dry air displaced convection from the surface low, leaving it exposed.[14] Considerable uncertainty in the forecast for Florence arose, as weather models began to depict various solutions.[15] Fluctuations in organization and intensity continued through September 3.[16][17]

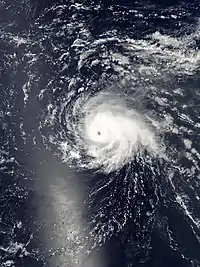

Unexpected intensification

Development of a small central dense overcast and a mid-level eye feature signified that Florence achieved hurricane strength early on September 4, roughly 1,240 miles (2,000 km) west-northwest of the Cape Verde islands.[18][19] Broad-scale conditions—moderate wind shear, sea surface temperatures below 81 °F (27 °C), and low relative humidity values—did not favor further intensification.[1] However, these conditions were averaged over a large area and did not accurately represent localized conditions in the vicinity of Florence.[20] The compact system unexpectedly rapidly organized within a small area of low wind shear.[21] The hurricane's core structure and outer banding improved markedly, catching forecasters off-guard and intensifying beyond model outputs.[22] In stark contrast to model guidance,[23] Florence continued to intensify and attained major hurricane status around 12:00 UTC on September 5. Sustained winds rose to 130 mph (215 km/h) and its pressure fell to 950 mbar (hPa; 28.05 inHg); this ranked it as a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale.[1] Situated at 22.7°N 46.6°W,[24] Florence became the northernmost Category 4 hurricane east of 50°W.[25]

The hurricane's unforeseen intensification caused it to track farther north, out of the localized low shear.[26] Persistent shear finally took its toll on Florence on September 6 through September 7, causing convection to become asymmetrical and tilting the storm's core southwest to northeast.[27][28] By the early hours of September 7, rapid degradation of Florence's structure occurred. Its low-level circulation became exposed as convection became displaced to the northeast and the previously well-defined eye dissipated. Scatterometer data revealed the system weakened to tropical storm intensity by 00:00 UTC.[1][26] Meteorologist Robbie Berg described the intensity forecasts for Florence as a "self-defeating prophecy" owing to the "nuances of the environmental shear".[26][29] A building mid-level ridge halted Florence's northward movement, leading to a slow westward turn.[26][29] Weather models became increasingly consistent on the storm's future track, leading to greater confidence in a major impact to the Southeastern United States.[30] This threat was enhanced by the downstream effects of Typhoon Jebi's extratropical remnant influencing a ridge off the eastern United States which, in turn, forced a trough away from Florence faster than initially anticipated.[31] This trajectory proved climatologically unusual, with United States hurricane impacts primarily originating farther south and west of Florence's position on that day.[32]

United States approach

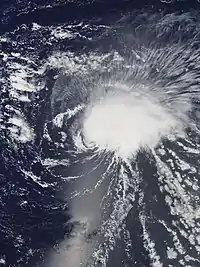

Environmental conditions became increasingly conducive to reorganization on September 8 as NOAA Hurricane Hunters began reconnaissance of the cyclone.[33] Convective banding blossomed around the storm and a formative eye appeared on satellite imagery.[34] The storm's central dense overcast became more defined and a complete eyewall developed within its core. Florence reattained hurricane-status around 12:00 UTC on September 9, with the Hurricane Hunters observing 76 mph (122 km/h) sustained winds at the surface.[1][35] Fueled by sea surface temperatures of 84.2 to 85.1 °F (29 to 29.5 °C), Florence rapidly intensified overnight. Convective bursts with frequent lightning surrounded the eyewall,[36] giving rise to a well-defined 12 mi (19 km) wide eye. Expanding outflow ventilated the cyclone, enabling continued growth.[37] The system rapidly achieved Category 4 intensity by 16:00 UTC, with reconnaissance aircraft recording surface winds near 130 mph (215 km/h) and a pressure of 946 mbar (hPa; 27.93 inHg).[38] The hurricane's motion accelerated and shifted northwest by this time, a trajectory it would maintain for several days.[37]

.jpg.webp)

Hurricane Florence achieved its initial peak intensity late on September 10 with sustained winds of 140 mph (220 km/h) and a pressure of 940 mbar (hPa; 27.76 inHg).[1][nb 2] The extent of hurricane-force winds doubled in size and well-defined mesovortices rotated along the inner eyewall.[39] Slight weakening ensued thereafter as an eyewall replacement cycle started; convection surrounding the eyewall became ragged and the eye itself filled.[40][41] This process completed the following day, with the newly formed eye spanning 35 mi (55 km) across. Extensive outflow became established over the cyclone, extending northwest and east, providing ample ventilation and deformation which enabled Florence to continue expanding.[42] The system intensified again and reached its peak intensity with winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a pressure of 937 mbar (hPa; 27.76 inHg) at 18:00 UTC.[1][nb 3] The future track of the hurricane became increasingly complex as it approached the Carolinas. A strengthening trough moving inland over the Pacific Northwest amplified ridging over the Northeastern United States and western Atlantic Ocean, steering Florence to the west-northwest. A collapse of steering currents was anticipated around the time of landfall on September 14, which would result in the hurricane meandering near the coast or just inland for a prolonged period of time.[43]

Fluctuations in the organization of Florence continued through the remainder of September 11 into September 12. Environmental conditions remained highly favorable for intensification and the NHC forecast the system to strengthen just below Category 5 status by September 13;[44] however, the system soon weakened and degraded to Category 3 status by 18:00 UTC.[45] Florence steadily grew in size during this time, with tropical storm-force winds extending 195 mi (315 km) by the end of September 12.[46] The hurricane's core soon unraveled on September 13 as mid-level wind shear increased and upwelling of colder water reduced available energy.[1] The hurricane's eyewall eroded entirely along the south side and convection became disrupted. Reconnaissance data revealed an ongoing eyewall replacement cycle, with a 25–35 mi (35–55 km) wide inner-core and 60–70 mi (95–110 km) wide outer-core. Furthermore, sustained surface winds fell to an estimated 110 mph (175 km/h), marking the cessation of Florence's tenure as a major hurricane.[47]

Landfall and dissipation

The outer rainbands of Hurricane Florence began affecting North Carolina during the latter half of September 13. Ample atmospheric moisture combined with strong upward lift from the anticyclone atop Florence yielded an environment conducive to widespread torrential precipitation. NEXRAD radar data from Morehead City indicated rainfall rates of 1 to 2 in (25 to 50 mm) per hour within these bands.[48] Florence's forward motion slowed throughout the day as the ridge steering it northwest built ahead of the cyclone toward the Appalachian Mountains. The previously disrupted eye rejuvenated; however, wind speeds within the storm continued to decrease.[49] Additional fluctuations in the hurricane's core resulted in erratic movement, including a brief stalling period approximately 100 mi (155 km) east-southeast of Wilmington.[50][51] By 21:00 UTC, sustained hurricane-force winds reached the North Carolina coastline.[50] Trudging west, the eye of Florence ultimately made landfall near Wrightsville Beach at 11:15 UTC on September 14 as a Category 1 hurricane with winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) and a central pressure of 956 mbar (hPa; 28.23 inHg).[1]

As the hurricane moved ashore, deep convection blossomed along the eastern side of Florence's core. A strong inflow band became established within this area, resulting in localized heavy rain along the Crystal Coast.[52] Rainfall rates within the western eyewall reached an estimated 3 in (75 mm) per hour while widespread accumulations of 1 to 2 in (25 to 50 mm) per hour fell within the eastern band. A rain gage in Swansboro indicated accumulations of 14 to 15 in (360 to 380 mm) by 14:34 UTC, exceeding radar estimations. Consistent flooding rains impacted Carteret County, prompting a flash flood emergency by this time. Although the hurricane continued its slow movement west, the rain band gradually propagated east resulting in no net movement.[53] Early on September 15, this band remained situated over Onslow, Carteret, Jones, Lenoir, and Wayne counties. A new rain band developed closer to the storm's core over New Hanover, Brunswick, Pender, Bladen, and Sampson counties. Catastrophic flash flooding from these bands ensued throughout the day, washing out roads and prompting water rescues.[54]

Although the center of Florence progressed inland over South Carolina, offshore convective available potential energy values of 1,000–2,000 J/kg and strong mid-level winds continued fueling the aforementioned rainbands.[56] A low-risk of tornadoes accompanied the heavy rain across North Carolina. Minimal diabatic heating stemming from the hurricane's lack of a thermal gradient kept the threat of tornadic storms low, with the primary driving force being ample atmospheric moisture.[57] Small-scale training supercells—series of severe storms that continuously develop, track across, and dissipate over the same areas—developed between Morehead City and Wilmington during the overnight hours of September 14–15.[58] Record flooding ensued along the Cape Fear, Northeast Cape Fear, Lumber, and Waccamaw rivers; nine USGS river gauges observed all-time crests. Flooding persisted along multiple rivers for more than a week after the storm. Approximately 86,000 homes across North and South Carolina were flooded or otherwise damaged.[59] Total damage between the two states reached an estimated $24 billion, ranking Florence as the ninth-costliest hurricane in United States' history.[1]

Florence weakened below hurricane strength by 00:00 UTC on September 15. Its close proximity to the coastline enabled it to maintain its organization and only slowly degrade.[1] Throughout the majority of the day intense rainbands persisted over southern North Carolina, with six-hourly accumulations averaging 3 to 6 in (76 to 152 mm) in two bands extending from Brunswick to Bladen counties and Pender to Sampson counties.[60] Aided by an anticyclone, this band stretched across 350 mi (565 km) along the eastern side of Florence. The heaviest rains shifted to South Carolina early on September 16; estimated rainfall rates reached 2 to 3 in (51 to 76 mm) per hour in Dillon, Marion, and Marlboro counties.[61]

The system finally weakened to a tropical depression over South Carolina by 18:00 UTC on September 16, more than two days after it made landfall. Florence accelerated north along the western edge of the ridge previously steering it west. It eventually became extratropical over West Virginia on September 17.[1] Heavy rains propagated north along with the circulation center; however, rainbands extended from Virginia to South Carolina through September 17 with a narrow band of convection pivoting along the eastern slopes of the Appalachian Mountains.[62] An approaching frontal system caused the remnant system to accelerate east, and ultimately resulted in its dissipation over Massachusetts on September 18.[1] Precipitation gradually subsided as the system weakened and the flooding threat lessened accordingly. Moderate rain with localized areas of heavy precipitation extended into Pennsylvania, New York, and southern New England on September 18.[63]

Notes

- A Potential Tropical Cyclone is a storm system that is not yet a tropical cyclone but has a high likelihood of becoming one and is anticipated to produce tropical storm or hurricane conditions on land within 48 hours.[6][7]

- Dropsonde data at this time indicated peak winds of 184 mph (296 km/h) aloft; however, surface based observations by reconnaissance indicated surface winds to be significantly lower.[1]

- Florence's peak intensity was based on a reduction of reconnaissance flight-level winds of 163–165 mph (262–266 km/h) at 12:23 UTC and continued improvement of the hurricane's inner core thereafter.[1]

References

- Stacy Stewart and Robbie Berg (May 30, 2019). Hurricane Florence (AL062018) (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- Robbie Berg (August 28, 2018). Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Lixion Avila (August 29, 2018). Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Lixion Avila (August 30, 2018). Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Lixion Avila (August 30, 2018). Potential Tropical Cyclone Six Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- "[National Hurricane Center Glossary: Potential Tropical Cyclone". National Hurricane Center. 2019. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- Chris Dolce (September 13, 2019). "What Is a Potential Tropical Cyclone?". The Weather Channel. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Lixion Avila (August 30, 2018). Potential Tropical Cyclone Six Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Robbie Berg (August 31, 2018). Potential Tropical Cyclone Six Discussion Number 4 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Lixion Avila (August 31, 2018). Tropical Depression Six Discussion Number 6 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Jack Beven (September 1, 2018). Tropical Depression Six Discussion Number 7 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Robbie Berg (September 1, 2018). Tropical Storm Florence Discussion Number 8 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- David Zelinsky (September 2, 2018). Tropical Storm Florence Discussion Number 12 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Stacy Stewart (September 2, 2018). Tropical Storm Florence Discussion Number 13 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Michael Brennan (September 2, 2018). Tropical Storm Florence Discussion Number 14 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- David Zelinsky (September 3, 2018). Tropical Storm Florence Discussion Number 16 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Michael Brennan (September 3, 2018). Tropical Storm Florence Discussion Number 17 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Robbie Berg (September 4, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 21 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Robbie Berg (September 4, 2018). Hurricane Florence Advisory Number 21 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Philippe Papin [@pppapin] (September 5, 2018). "Inspired by NHC's earlier disco, I wanted to play with #VWS calculated at different radii n/ #Florence. After removing the vortex, the radius size is key. Shear decreases markedly for smaller radii & anything larger than 2 degrees is probably too big. See animated graphic below:" (Tweet). Retrieved April 6, 2020 – via Twitter.

- Robbie Berg and Jamie Rhome (September 5, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 25 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Dave Roberts (September 5, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 24 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Robbie Berg and Jamie Rhome (September 5, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 26 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Robbie Berg and Jamie Rhome (September 5, 2018). Hurricane Florence Advisory Number 26 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Sam Lillo [@splillo] (September 5, 2018). "Intensity at 18z has been increased to 115kt -- #Florence is officially a category 4 hurricane. At 22.4N / 46.2W, this also makes #Florence the furthest north category 4 hurricane east of 50W ever recorded in the Atlantic" (Tweet). Retrieved September 9, 2018 – via Twitter.

- Robbie Berg (September 6, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 29 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- Eric Blake (September 6, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 27 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- David Zelinsky (September 6, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 28 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- Eric Blake (September 7, 2018). Tropical Storm Florence Discussion Number 31 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- Robbie Berg (September 7, 2018). Tropical Storm Florence Discussion Number 33 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- Philippe Papin [@pppapin] (September 7, 2018). "A lot of huge track shifts we've seen the last 3-4 days are also related to the downstream impact of #Jebi's #ET. Big reconfiguration of the waveguide to favor a ridging on the east coast. That ridge kicked the first trough N of Florence out much faster than originally fcasted" (Tweet). Retrieved September 18, 2019 – via Twitter.

- Michael Lowry [@MichaelRLowry] (September 7, 2018). "For historical perspective, most landfalling U.S. hurricanes have tracked much farther south and west of #Florence's current position" (Tweet). Retrieved September 9, 2018 – via Twitter.

- Robbie Berg (September 8, 2018). Tropical Storm Florence Discussion Number 38 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- Lixion Avila (September 9, 2018). Tropical Storm Florence Discussion Number 39 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- Eric Blake (September 9, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 41 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- Stacy Stewart (September 10, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 43 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- Eric Blake (September 10, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 44 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- Eric Blake (September 10, 2018). Hurricane Florence Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- Eric Blake (September 10, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 46 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Jack Beven (September 11, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 47 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Daniel Brown (September 11, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 48 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Stacy Stewart (September 11, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 49 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Stacy Stewart (September 11, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 50 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Richard Pasch (September 12, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 51 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Stacy Stewart (September 12, 2018). Hurricane Florence Intermediate Advisory Number 53A (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Stacy Stewart (September 12, 2018). Hurricane Florence Advisory Number 54 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Jack Beven (September 13, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 55 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Joshua Weiss (September 13, 2018). Mesoscale Precipitation Discussion: #0830 (Technical Discussion). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Stacy Stewart (September 13, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 57 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Stacy Stewart (September 13, 2018). Hurricane Florence Discussion Number 58 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Stacy Stewart (September 13, 2018). Hurricane Florence Advisory Number 58 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Richard Otto (September 14, 2018). Mesoscale Precipitation Discussion: #0834 (Technical Discussion). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- David Roth (September 14, 2018). Mesoscale Precipitation Discussion: #0836 (Technical Discussion). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Richard Otto (September 15, 2018). Mesoscale Precipitation Discussion: #0839 (Technical Discussion). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- David Roth (September 14, 2018). Mesoscale Precipitation Discussion: #0837 (Technical Discussion). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- Richard Otto (September 15, 2018). Mesoscale Precipitation Discussion: #0842 (Technical Discussion). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- Andy Dean, Chris Broyles, and Nathan Wendt (September 14, 2018). Sep 14, 2018 0600 UTC Day 1 Convective Outlook (Report). Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved September 24, 2018.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Andy Dean and Chris Broyles (September 14, 2018). Sep 15, 2018 0100 UTC Day 1 Convective Outlook (Report). Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- "Hurricane Florence: September 14, 2018". National Weather Service Forecast Office in Wilmington, North Carolina. 2018. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- Frank Pereira (September 15, 2018). Mesoscale Precipitation Discussion: #0845 (Technical Discussion). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- Richard Otto (September 16, 2018). Mesoscale Precipitation Discussion: #0848 (Technical Discussion). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- Alex Lamers (September 17, 2018). Mesoscale Precipitation Discussion: #0858 (Technical Discussion). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- Richard Otto (September 18, 2018). Mesoscale Precipitation Discussion: #0860 (Technical Discussion). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 18, 2019.