Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) or extrinsic allergic alveolitis (EAA) is a rare immune system disorder that affects the lungs.[1] It is an inflammation of the airspaces (alveoli) and small airways (bronchioles) within the lung, caused by hypersensitivity to inhaled organic dusts and molds.[2] People affected by this type of lung inflammation (pneumonitis) are commonly exposed to the dust and mold by their occupation or hobbies.[2]

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Allergic alveolitis, bagpipe lung, extrinsic allergic alveolitis (EAA) |

| |

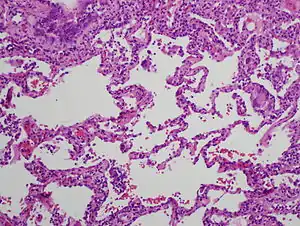

| High magnification photomicrograph of a lung biopsy taken showing chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (H&E), showing mild expansion of the alveolar septa (interstitium) by lymphocytes. A multinucleated giant cell, seen within the interstitium to the right of the picture halfway down, is an important clue to the correct diagnosis. | |

| Specialty | Respirology |

Signs and symptoms

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is categorized as acute, subacute, and chronic based on the duration of the illness.[3]

Acute

In the acute form of HP, symptoms may develop 4–6 hours following heavy exposure to the provoking antigen. Symptoms include fever, chills, malaise, cough, chest tightness, dyspnea, rash, swelling and headache. Symptoms resolve within 12 hours to several days upon cessation of exposure.[4]

Acute HP is characterized by poorly formed noncaseating interstitial granulomas and mononuclear cell infiltration in a peribronchial distribution with prominent giant cells.[4]

On chest radiographs, a diffuse micronodular interstitial pattern (at times with ground-glass density in the lower and middle lung zones) may be observed. Findings are normal in approximately 10% of patients." In high-resolution CT scans, ground-glass opacities or diffusely increased radiodensities are present. Pulmonary function tests show reduced diffusion capacity of lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Many patients have hypoxemia at rest, and all patients desaturate with exercise.[4] Extrinsic allergic alveolitis may eventually lead to interstitial lung disease.[5]

Subacute

Patients with subacute HP gradually develop a productive cough, dyspnea, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and pleurisy. Symptoms are similar to the acute form of the disease, but are less severe and last longer. On chest radiographs, micronodular or reticular opacities are most prominent in mid-to-lower lung zones.[4] Findings may be present in patients who have experienced repeated acute attacks.

The subacute, or intermittent, form produces more well-formed noncaseating granulomas, bronchiolitis with or without organizing pneumonia, and interstitial fibrosis.[4]

Chronic

In chronic HP, patients often lack a history of acute episodes. They have an insidious onset of cough, progressive dyspnea, fatigue, and weight loss. This is associated with partial to complete but gradual reversibility. Avoiding any further exposure is recommended. Clubbing is observed in 50% of patients. Tachypnea, respiratory distress, and inspiratory crackles over lower lung fields often are present.[4]

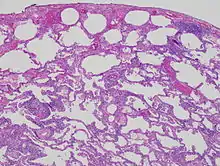

On chest radiographs, progressive fibrotic changes with loss of lung volume particularly affect the upper lobes. Nodular or ground-glass opacities are not present. Features of emphysema are found on significant chest films and CT scans.[4]

Chronic forms reveal additional findings of chronic interstitial inflammation and alveolar destruction (honeycombing) associated with dense fibrosis. Cholesterol clefts or asteroid bodies are present within or outside granulomas.[4] Much like the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, chronic HP is related to increased expression of Fas antigen and Fas ligand, leading to increased epithelial apoptosis activation in the alveoli.[6]

In addition, many patients have hypoxemia at rest, and all patients desaturate with exercise.

Pathophysiology

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis involves inhalation of an antigen. This leads to an exaggerated immune response (hypersensitivity). Type III hypersensitivity and type IV hypersensitivity can both occur depending on the cause.[7]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based upon a history of symptoms after exposure to the allergen and clinical tests. A physician may take blood tests, seeking signs of inflammation, a chest X-ray and lung function tests. The sufferer shows a restrictive loss of lung function.

Precipitating IgG antibodies against fungal or avian antigens can be detected in the laboratory using the traditional Ouchterlony immunodiffusion method wherein 'precipitin' lines form on agar plate. The ImmunoCAP technology has replaced this time-consuming, labor-intensive method with their automated CAP assays and FEIA (Fluorescence enzyme immunoassay) that can detect IgG antibodies against Aspergillus fumigatus (Farmer's lung or for ABPA) or avian antigens (Bird Fancier's Lung). [8]

Although overlapping in many cases, hypersensitivity pneumonitis may be distinguished from occupational asthma in that it is not restricted to only occupational exposure, and that asthma generally is classified as a type I hypersensitivity.[9][10] Unlike asthma, hypersensitivity pneumonitis targets lung alveoli rather than bronchi.[11]

Lung biopsy

Lung biopsies can be diagnostic in cases of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, or may help to suggest the diagnosis and trigger or intensify the search for an allergen. The main feature of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis on lung biopsies is expansion of the interstitium by lymphocytes accompanied by an occasional multinucleated giant cell or loose granuloma.[12][13]

When fibrosis develops in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, the differential diagnosis in lung biopsies includes the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias.[14] This group of diseases includes usual interstitial pneumonia, non-specific interstitial pneumonia and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, among others.[12][13]

The prognosis of some idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, e.g. idiopathic usual interstitial pneumonia (i.e. idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis), are very poor and the treatments of little help. This contrasts the prognosis (and treatment) for hypersensitivity pneumonitis, which is generally fairly good if the allergen is identified and exposures to it significantly reduced or eliminated. Thus, a lung biopsy, in some cases, may make a decisive difference.

Types

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis may also be called many different names, based on the provoking antigen. These include:

| Type[15] | Specific antigen | Exposure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bird fancier's lung Also called bird breeder's lung, pigeon breeder's lung, and poultry worker's lung |

Avian proteins | Feathers and bird droppings [16] | ||

| Bagassosis Exposure to moldy molasses |

Thermophilic actinomycetes[16] | Moldy bagasse (pressed sugarcane) | ||

| Cephalosporium HP | Cephalosporium | Contaminated basements (from sewage) | ||

| Cheese-washer's lung | Penicillum casei[16] or P. roqueforti | Cheese casings | ||

| Chemical worker's lung – Isocyanate HP | Toluene diisocyanate (TDI), Hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI), or Methylene bisphenyl isocyanate (MDI) | Paints, resins, and polyurethane foams | ||

| Chemical worker's lung[16] – Trimellitic anhydride (TMA) HP | Trimellitic anhydride[16] | Plastics, resins, and paints | ||

| Coffee worker's lung | Coffee bean protein | Coffee bean dust | ||

| Compost lung | Aspergillus | Compost | ||

| Detergent worker's disease | Bacillus subtilis enzymes | Detergent | ||

| Familial HP Also called Domestic HP |

Bacillus subtilis, puffball spores | Contaminated walls | ||

| Farmer's lung | The molds

The bacteria

|

Moldy hay | ||

| Hot tub lung | Mycobacterium avium complex | Mist from hot tubs | ||

| Humidifier lung | The bacteria

The fungi The amoebae

|

Mist generated by a machine from standing water | ||

| Japanese summer house HP Also called Japanese summer-type HP | Trichosporon cutaneum | Damp wood and mats | ||

| Laboratory worker's lung | Male rat urine protein | Laboratory rats | ||

| Lycoperdonosis | Puffball spores | Spore dust from mature puffballs[17] | ||

| Malt worker's lung | Aspergillus clavatus[16] | Moldy barley | ||

| Maple bark disease | Cryptostroma corticale[16] | Moldy maple bark | ||

| Metalworking fluids HP | Nontuberculous mycobacteria | Mist from metalworking fluids | ||

| Miller's lung | Sitophilus granarius (wheat weevil)[16] | Dust-contaminated grain[16] | ||

| Mollusc shell HP | Aquatic animal proteins | Mollusc shell dust | ||

| Mushroom worker's lung | Thermophilic actinomycetes | Mushroom compost | ||

| Peat moss worker's lung | Caused by Monocillium sp. and Penicillium citreonigrum | Peat moss | ||

| Pituitary snuff taker's lung | Pituitary snuff | Medication (Diabetes insipidus) | ||

| Potato peeler's lung | Potatococcus, Potato skin (bacterium) spp | Potato dipped in immune globulins | ||

| Sauna worker's lung | Aureobasidium, Graphium spp | Contaminated sauna water | ||

| Sequoiosis | Aureobasidium, Graphium spp | Redwood bark, sawdust | ||

| Streptomyces HP | Streptomyces albus | Contaminated fertilizer | ||

| Suberosis | Penicillium glabrum (formerly known as Penicillium frequentans) | Moldy cork dust | ||

| Tap water HP | Unknown | Contaminated tap water | ||

| Thatched roof disease | Saccharomonospora viridis | Dried grass | ||

| Tobacco worker's lung | Aspergillus spp | Moldy tobacco | ||

| Trombone Player's lung (Brass Player's Lung) | Mycobacterium chelonae | Various Mycobacteria inside instruments | [18] | [19] |

| Well-emptier's lung | Wellercoccus spp | Contaminated well water | ||

| Wine-grower's lung | Botrytis cinerea mold | Moldy grapes | ||

| Woodworker's lung | Alternaria, Penicillium spp | Wood pulp, dust |

Of these types, Farmer's Lung and Bird-Breeder's Lung are the most common. "Studies document 8-540 cases per 100,000 persons per year for farmers and 6000-21,000 cases per 100,000 persons per year for pigeon breeders. High attack rates are documented in sporadic outbreaks. Prevalence varies by region, climate, and farming practices. HP affects 0.4–7% of the farming population. Reported prevalence among bird fanciers is estimated to be 20-20,000 cases per 100,000 persons at risk." [4]

Treatment

The best treatment is to avoid the provoking allergen, as chronic exposure can cause permanent damage. Corticosteroids such as prednisolone may help to control symptoms but may produce side-effects.[20]

Additional images

High magnification micrograph of hypersensitivity pneumonitis showing granulomatous inflammation. Trichrome stain.

High magnification micrograph of hypersensitivity pneumonitis showing granulomatous inflammation. Trichrome stain.

References

- "Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis". National Institute of Health (NIH) National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

- Quirce S, Vandenplas O, Campo P, et al. (2016). "Occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis: an EAACI position paper". Allergy. 71 (6): 765–79. doi:10.1111/all.12866. PMID 26913451.

- http://www.ucsfhealth.org/adult/medical_services/pulmonary/ild/conditions/hp/signs.html signs and symptoms

- Sharma, Sat. Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis. eMedicine, June 1, 2006.

- Ismail T, McSharry C, Boyd G (2006). "Extrinsic allergic alveolitis". Respirology. 11 (3): 262–8. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00839.x. PMID 16635083. S2CID 13460021.

- Jinta, Torahiko (October 2010). "The Pathogenesis of Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis in Common With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis". American Society for Clinical Pathology. 134 (4): 613–620. doi:10.1309/AJCPK8RPQX7TQRQC. PMID 20855643 – via Oxford Academic.

- Mohr LC (September 2004). "Hypersensitivity pneumonitis". Curr Opin Pulm Med. 10 (5): 401–11. doi:10.1097/01.mcp.0000135675.95674.29. PMID 15316440. S2CID 31344045.

- Khan, Sujoy; Ramasubban, Suresh; Maity, Chinmoy K (1 July 2012). "Making the case for using the Aspergillus immunoglobulin G enzyme linked immunoassay than the precipitin test in the diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis". Indian Journal of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 26 (2): 89. doi:10.4103/0972-6691.112555. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "Lecture 14: Hypersensitivity". Archived from the original on 2006-02-06. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- "Allergy & Asthma Disease Management Center: Ask the Expert". Archived from the original on 2007-02-16. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- Page 503 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- Mukhopadhyay, Sanjay. "Pathology of Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis", Retrieved on 3 May 2013.

- Mukhopadhyay S, Gal AA (2010). "Granulomatous lung disease: an approach to the differential diagnosis". Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 134 (5): 669–690. doi:10.1043/1543-2165-134.5.667 (inactive 2021-01-17). PMID 20441499.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Ohtani Y, Saiki S, Kitaichi M, et al. (August 2005). "Chronic bird fancier's lung: histopathological and clinical correlation. An application of the 2002 ATS/ERS consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias". Thorax. 60 (8): 665–71. doi:10.1136/thx.2004.027326. PMC 1747497. PMID 16061708.

- Enelow, RI (2008). Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 1161–72. ISBN 978-0-07-145739-2.

- Kumar 2007, Table 13-5

- Munson EL, Panko DM, Fink JG (1997). "Lycoperdonosis: Report of two cases and discussion of the disease". Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 19 (3): 17–24. doi:10.1016/S0196-4399(97)89413-5.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2014-05-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Sour Note: Sax Can Cause Lung Disease". ABC News. 7 September 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis Treatment - Conditions & Treatments - UCSF Medical Center". www.ucsfhealth.org. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

See also

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |