Immigrant health in Australia

Immigration is the movement of an individual or group of peoples to a foreign country to live permanently.[1] Since 1788, when the first British settlers arrived in Botany Bay, immigrants have travelled from across the world to establish a life in Australia.[2] The reason for people or groups of peoples moving to Australia varies. Such reasons can be due to seeking work or even refuge from third world countries. The health of immigrants entering Australia varies depending on the individual's country of origin and the circumstance of which they came, as well as their state of travel to Australia. Immigrants are known to enter Australia both legally and illegally, and this can affect one's health immensely.[3] Once in Australia, immigrants are given the opportunity to access a high quality of healthcare services, however, the usage of these services can differ dependent on the culture and place of birth of the individual.[4] Researchers have proven this. Australia has strict health regulations that have to be met before one is allowed access into Australia and can determine if one is granted or denied such access. The quarantine process of immigrants into Australia has been in place since 1830, starting at the North Head Quarantine Station and continues all over Australia.[5]

Australia's immigrants

Europeans

In 1788, the first fleet of British immigrants established a colony in Australia. The arrival of the Europeans in the 1800s, saw those from Italy, Greece, Poland, Malta, Russia and France land on the shores of Australia.[6] Upon embarking, it is expected that the European immigrants would have carried infectious diseases aboard the ships, and given the nature of the vessels, any disease would have spread quickly among the passengers. Reports by Mark Stainforth suggest that many forms of bacteria and viruses caused high levels of illness and on-board deaths among those European immigrants travelling to Australia.[7]

Diagnosis of immigrant morbidity on board ship (1837–39)[7]

| Disease | Modern Equivalent | Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Diarrhoea | Diarrhoea | 350 |

| Obstipatio | Constipation | 160 |

| Cattarhus | Influenza | 147 |

| Continuae Synochus | Typhoid | 143 |

| Scareltina | Scarlett fever | 133 |

| Ophthalmia | various | 81 |

| Colica | various | 67 |

| Dysentaria | Dysentery | 68 |

| Cyanchie Tonsilons | various | 59 |

| Tabes | various | 49 |

Because of these viruses and infections that spread among European immigrants before reaching Australia, upon arrival, a majority of immigrants were of ill health.[7] The immigration of European settlers introduced such bacteria and viruses to Australia.[6][7]

1850: Measles were reported in Australia brought over by the European.[9]

1900: Bubonic plague founded among European immigrants[9]

1982: HIV was detected in a European man.[10]

Chinese

According to the 1861 Colonial Census, Chinese-born persons made up 3.4% of the Australian population,[11] equating to approximately 38,258 Chinese in Australia after 1842 when the Chinese first settled in Australia. Some arrived in Australia hoping to escape civil disorder in China, although the majority of Chinese migrated to Australia after hearing about the gold rush.[11]

Within Australia, the average life expectancy is 81.7 years, while China-born individuals have an average of 74.7 years.[11][12] The Queensland Health Multicultural Services suggests that Ischaemic heart disease, cancer and cerebrovascular disease are the major causes of death of China-born persons in Australia. Such cancers that have been identified include nasopyarynx, lung, intestine, rectum, stomach and liver cancer, all of which are prominent among Chinese immigrants.[11]

Afghans

From the 1860s, "Afghan" cameleers, who came mainly from Afghanistan, but also British India and other countries, settled in Australia, establishing work helping to open up outback Australia.[6]

Afghans who have migrated to Australia more recently face several disadvantages when accessing health services. Disadvantages include language barriers, a lack of translators in Australian health services, and the incompatibility of some Australian healthcare services and procedures with Islamic beliefs.[13] The migrants may experience a sense of alienation and lack of belonging as they are put in a situation that makes them feel like outcasts compared to the rest of Australia. However the Queensland Health Multicultural Services have suggested that Afghan migrants use the health services just as much as Australian-born individuals.[13]

Children

The Royal Children's Hospital in Melbourne have conducted a study that identifies the following among children who have immigrated to Australia.[14]

| Infection | Percentage of children |

|---|---|

| Anaemia | 10 – 30% |

| Hepatitis B | 2 – 7% |

| Pathogenic faecal parasites | 14 – 42% |

| Tuberculosis | 25 – 55% |

Quarantine and health requirements

Early years

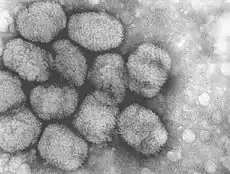

In the 1830s, the immigrants that arrived by boat on the shores of Sydney were suspected to be carrying contagious diseases. During this period, influenza, typhoid, scarlet fever and whopping cough were all found on European ships arriving in Australia.[7] To contain such diseases, the ships were stopped at North Head Quarantine Station where the authority would place the passengers and crew into quarantine.[6] The Australian Government (2015) suspects that each passenger would have spent on average, 40 days in quarantine before being released into Australia, as Australian residents.[6] Each experience within North Head varied and was dependent on class. Some immigrants were exposed to further disease, disempowerment and in some cases death. In the beginning, North Head Quarantine Station provided tents for those immigrants who came to Australia.[6] However, in 1837, those who appeared to be healthy were those who were granted accommodation in the tents, while those who were sick were required to stay on the ship.[6] The Australian government suggests that in the year of 1837, 295 healthy immigrants were kept ashore while those who were contagious or otherwise were kept on the ship. The North Head Quarantine Station's facilities continued to grow. However, between 1860 and 1870, the quarantine station took a turn for the worst when the world economy decelerated along with immigration. As a result, an outbreak of smallpox occurred due to insufficient maintenance of the North Head Quarantine Station.[6] It was only in 1909, when the Commonwealth government took over North Head Quarantine, that the station attained a maximum volume of 1200 people.

Government health requirements

In order to ensure Australia's health and safety, the Government is required to examine all immigrants prior to entering Australia. Those who seek either a permanent or temporary visa are part of this application. All candidates are checked for Tuberculosis, HIV and Hepatitis, Yellow fever, Polio and the Ebola virus disease (EVD). In order to be allowed access into Australia, you must be cleared of all of these diseases and deemed to be no threat to Australian communities.[6]

Australian health services

Current health care system

The Medicare system in Australia is a publicly funded system that is designed to provide heavily subsidised costs for all Australians, including those foreign born immigrants who either have a citizenship, a working visa, a permanent visa, or one who is married to an Australian citizen.[4]

Health care difficulties for immigrants

For those who migrate to Australia, there are many disadvantages in the way of healthcare. The Australian government provides well supported healthcare for immigrants, however, those immigrants who arrive in Australia are struck by culture and communication barriers as well as a lack of knowledge when it comes to the cost of health services and knowing their rights.[5]

Cultural barriers

Cultural barriers felt by immigrants include the Australians perceptions of health as well as their behaviour when sick.[5] Such differences are determined by ones cultural heritage. It is also prominent that some immigrants are concerned that doctors will not recognise or understand their specific cultural needs. Such examples include the needs of women from the Middle East. Such women are fearful of male doctors examining them.[5] The ABC (2015) states that "different cultural groups have specific expectations. For example, Jehovah's Witness followers will refuse to have blood transfusions, believing it is polluting."[5][15]

Communication barriers

For those immigrants coming to Australia from non-English speaking backgrounds, communication barriers can influence one's health experience, whether it be negative or positive.[5][13] The ABC (2015) states that non-English speaking immigrants can turn to saying 'yes' in stressful situation in order to avoid further communication with healthcare services.[5] This can have great impacts on the individual as they may not receive the help they need as a result, or they will choose not to contact health services as they are wary of the communication barriers and believe it is easier to avoid the situation. This could result in the individual's health deteriorating as a result of lack of attention.[5]

Cost of healthcare

When immigrants arrive in Australia, it is evident that a lack of money and understanding of the healthcare system can lead to immigrants avoiding the services. Therefore, it is vital for immigrants, upon arrival, are noted of their rights in regards to free healthcare. Those immigrants who have access to Medicare are:

- Permanent residents[5]

- Those who await the final process of their permanent residency claim.[5]

- Countries such as Finland, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Italy, Malta, Ireland and New Zealand have an agreement with the Australian healthcare system that grants immigrants from the above countries with access to Medicare.[5]

Patient rights

It has been identified that immigrants from non-English speaking backgrounds, tend to feel less empowered, resulting in the patients becoming reticent. Non-English speak immigrants tend not to ask questions. As a result, many individuals are discouraged from visiting the services again, which can lead to the ill health of immigrants that are new to Australia.[5]

These factors can be reduced if new arrivals to Australia are aware of their rights.[5][16] All patients have the right to:

- Ask for a doctor of a particular sex.

- What privacy they wish for.

- An interpreter.

- Complain if they feel necessary.

Between 2007 and 2008, an Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights was established by the commission.[16] This charter provides a clear outline of the rights of those seeking healthcare, and is directed at patients, consumers, families, carers and service providers.[16] This charter can be applied in all health settings in Australia. These include, public hospitals,. general practices and other environments.

See the Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights below:

Expectations of the Australian health system[16]

| Patient rights | What this means |

| Access | |

| Patients have the right to health care | Patients can access services to address their healthcare needs. |

| Safety | |

| Patients have a right to receive safe and

high quality care |

Patients have a right to receive safe and high quality service,

provided with professional care, skill and competence. |

| Respect | |

| Patients have the right to be shown respect,

dignity and consideration |

The care provided shows respect to a patient, their culture,

beliefs, values and personal characteristics. |

| Communication | |

| Patients have a right to be informed about services,

treatment, options and costs in a clear and open way. |

Patients should receive open, timely and appropriate communication about

their health care in a way they can understand. |

| Participation | |

| Patients have a right to be included in decisions and

choices about their care. |

Patients may join in making decisions and choices about their care

and about health service planning. |

| Privacy | |

| Patients have a right to privacy and confidentiality of their

personal information. |

A patient's personal privacy is maintained and proper handling of

their personal health and other information is assured. |

| Comment | |

| Patients have a right to comment on their care and to have

their concerns addressed. |

Patients can comment on or complain about their care and have their

concerns dealt with properly and promptly. |

Health studies

A study has been undertaken, comparing the mental health of men and women in Australia, identifying the differences between Australian born and foreign born individuals.[17] To achieve the following results, a diagnosis of mental health, current depression, medical service use and use of medication have been studied.[17]

Three groups of individuals:[17]

- Australian born

- English speaking foreign born

- Non-English speaking foreign born

The study has proven that both foreign born and Australian born groups of people access mental health services at an equal rate. However, non-English speaking foreign born men have demonstrated an increased risk of mental health issues and access health services less than Australian born men.[17] These results suggest that the government and health services need to be made aware of these particular health issues among non-English speaking foreign born men, in particular those men who unmarried, unemployed and live alone. The findings of this study identify the importance of social support to prevent mental health issues.[17]

Health of illegal immigrants

Whilst most immigrants and refugees travel to Australia legally, there are others who travel to Australia illegally.[3][18] Those who seek refuge in Australia illegally travel by boat, most of which are intercepted by the Royal Australian Navy patrolling the Australian border. From there, the Royal Australian Navy pass the refugees on to Australian Customs for detention.[3] There are many risks associated with entering Australia illegally and considering the conditions of travel, the deterioration of persons on board is prevalent.[3][18]

Most immigrants and refugees have been exposed to a variety of infectious diseases and psychological trauma, making the health of these individuals paramount for the Health professionals working in detention centres.[18] It is exceedingly difficult to acquire a precise medical history of the individuals considering the circumstances of which most refugees and illegal immigrants have escaped from.[3]

Dependent on the individual and their country of origin, the degree of nutritional and infectious disease varies. However, it has been noted that upper and lower respiratory tract infection, parasitic and intestinal infections are frequent findings in a number of illegal immigrants.[3]

Within Australian detention centres and amongst illegal immigrants, the presence of HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis A and B have been detected, prompting concerns for fellow detainees. However, such diseases appear to be low in Australia.[3]

Whilst the minority of illegal immigrants are females, pregnancy has been evident and therefore maternal healthcare is vital to ensure the health of both the mother and unborn child. Dental health amongst detainees is poor with the severe cases being acknowledged and attended to within the detention centres.[3]

More than 20% of asylum seekers who seek refuge in Australia appear to have suffered as a result of torture prior to arriving in Australia.[18] Therefore, psychiatric conditions are prevalent in detention camps. Anxiety and stress within the facilities has been emphasised by the lack of social support, unemployment and discrimination.[18] This psychological stress felt by detainees can be enhanced by the confined environment of the detention camps. Amongst the men and women, children have also been reported for suffering prolonged psychological conditions. Whilst there are psychological impacts on the immigrants, there are also those who are affected by physical conditions such as osteomyelitis or epilepsy.[3][18]

Controversies

Immunisation

It is stated that vaccinations will not be given to those who arrive in Australia as refugees or asylum seekers due to the individual or group of people's country of origin and the different immunisation schedules that they uphold.[19] However, it has been suggested that refugees and asylum seekers should be vaccinated according to the Australian National Immunisation Program Schedule; unless documentation of prior immunisation is provided, catch-up vaccinations are required.[19] In this regard, it has been argued that it is necessary for immigrants to be immunised to ensure the health and safety of fellow Australians. Nevertheless, there is a competing principle to afford every immigrant and Australian citizen an equal opportunity to uphold their cultural beliefs.[19] In this regard, some have questioned the Australian government's right to strip these refugees and asylum seekers of their cultural beliefs and understandings in regards to their health.[14]

Prolonged health issues

In 1992, mandatory detention was introduced for refugees and asylum seekers entering Australia illegally.[20] However, the introduction of mandatory detention has triggered debate. The importance of protecting Australia's borders and integrity of Australia's immigration system was the initial reason for the policy,[20] while those who question the policy and Australian Government's decision argue whether it is good for both parties (the refugees and Australian citizens), stating that it is inhumane and ineffective as it is proven to cause further health issues for the refugees and asylum seekers.[21]

Philip Flood, the former Secretory of the Department of Foreign Affairs, undertook an investigation into mandatory detention.[20] Several circumstances of self-harm, psychiatric problems and sexual, verbal and physical abuse of children were documented by Flood.[20] The final report identifies and expresses concerns in regards to the condition of which the refugees and asylum seekers are living, as well the Department's management of long-term detention and the impact this can have on young children.[20]

This debate against mandatory detention identifies the negatives and prolonged health issues that can arise from long-term detention.[20] It has been recommended that once asylum seekers and refugees are cleared of the initial checks, such as those of identity and health, that they are then released into community detention or granted a bridging visa whilst waiting for their refugee status to be determined.[20] However, further studies prove that keeping such illegal immigrants in mandatory detention protects the Australian community whilst the legitimacy of the refugees and asylum seekers is being assessed.[22]

Use of force in immigration detention facilities

Those authorised officers within immigration detention centres are given the power to use force against asylum seekers and refugees.[23] This is stated within the 2015 bill to maintain good order of immigration facilities. The Australian Human Rights Commission recognises the environment of particular detention facilities and force may be essential in specific circumstances. However, the Commission argues that the bill is deficient because:[23]

- The necessity and reasonableness of force should be assessed in every situation. The force used must be consistent with the Crimes Act and the policies regarding the use of force in immigration detention facilities.

- The use and limits of force that is stated in the policies and procedures, should be included in the Act.

- The forceful movement of immigrants and force used upon children should be controlled and limited within immigration detention facilities.

It is evident that while force may be need in certain circumstances, the use of force must be appropriate and respect the immigrant's inherent right to be treated with respect.[23] Concerns have arisen in regards to 'authorised officers' abusing the rights of the detained immigrants and therefore reinforcing the recommendation for the Bill to be altered and reworded by the Australian Human Rights Commission will be able to ensure that use of force used in immigration facilities is managed and acted out appropriately.[23]

See also

References

- "immigration – definition of immigration in English from the Oxford dictionary". www.oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- "European discovery and the colonisation of Australia | australia.gov.au". www.australia.gov.au. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- Shaw, M. T. M.; Leggat, P. A. (2006). "Medical screening and the health of illegal immigrants in Australia". Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 4 (5): 255–258. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2005.06.013.

- Straiton, M.; Grant, J. F.; Winefield, H. R.; Taylor (2014). "Mental health in immigrant men and women in Australia: The north west adelaide health study. ". BMC Public Health. 14 (1): 1111–1111. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1111. PMC 4228163. PMID 25349060.

- "Consumer guides: Migrant health services". ABC. 3 April 2003. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Government, Australian. "Department of Immigration and Border Protection".

- Stainforth, Mark (1996). "Diet, disease and death at sea on the voyage to Australia, 1837–1839". International Journal of Maritime History.

- "The origin of the smallpox outbreak in Sydney in 1789 | Treaty Republic – Indigenous Australia Sovereignty, Genocide, Land Rights and Pay the Rent Issues". treatyrepublic.net. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- "Diseases and Epidemics – Entry – eMelbourne – The Encyclopedia of Melbourne Online". www.emelbourne.net.au. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- Australian Federation of AIDS Organisation (2015). "HIV and Australia: A short history".

- Services, Q., H., M. (2011) Chinese Australians. Retrieved from

- The World Factbook. [ps://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2147rank.html "Central Intelligence Agency"].

- Services, Q., H., M. (2011) Afghan Australians.

- "Immigrant Health Service : Overview of health issues in immigrant children". www.rch.org.au. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- DuBose, Edwin (1995). The Jahovah's Witness Tradition: Religious beliefs and healthcare decisions. The park ridge centre.

- "Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights | Safety and Quality". www.safetyandquality.gov.au. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- Straiton, Melanie; Grant, Janet F.; Winefield, Helen R.; Taylor, Anne (28 October 2014). "Mental health in immigrant men and women in Australia: the North West Adelaide health study". BMC Public Health. 14 (1): 1111. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1111. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 4228163. PMID 25349060.

- Newman, L.; Lightfoot, T.; Singleton, G.; Aroche, J.; Yong, C.; Eagar, S.; Detention Health, Advisory Group (2010). "Mental illness in Australian immigration detention centres". The Lancet. 375 (9723): 1344–1345. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60571-5. PMID 20399975.

- "Immigrant Health Service: Overview of health issues in immigrant children". www.rch.org.au. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- "Immigration detention in Australia – Parliament of Australia". www.aph.gov.au. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- "The 'Pacific Solution' revisited: a statistical guide to the asylum seeker caseloads on Nauru and Manus Island – Parliament of Australia". www.aph.gov.au. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- "ParlInfo – Australian Government assistance to refugees: fact versus fiction". parlinfo.aph.gov.au. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- "Use of force in immigration detention facilities | Australian Human Rights Commission". www.humanrights.gov.au. Retrieved 4 September 2015.