Information Research Department

The Information Research Department (IRD), was a secret Cold War propaganda department of the British Foreign Office, created to publish anti-communist propaganda, provide support and information to anti-communist politicians, academics, and writers, and to use weaponised disinformation and "fake news" to attack socialists and anti-colonial movements.[1][2] Soon after its creation, the IRD broke away from focusing solely on Soviet matters and began to publish pro-colonial propaganda intended to suppress pro-independence revolutions in Asia, Africa, Ireland, and the Middle East. The IRD was heavily involved in the publishing of books, newspapers, leaflets, journals, and even created publishing houses to act as propaganda fronts, most notably Ampersand Limited.[3] Operating for 29 years, the IRD was notable for being the longest-running covert government propaganda department in British history, the largest branch of the Foreign Office,[4] and the first major anglophone propaganda offensive against the USSR since the end of World War II. By the 1970s, the IRD was performing military intelligence tasks for the British Military in Ireland during The Troubles.[5]

Carlton House Terrace, the original home of the Information Research Department's propaganda activities | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1948 |

| Dissolved | 1977 |

| Jurisdiction | United Kingdom |

| Employees | Estimated 400-600 at height [1] |

| Parent agency | Foreign Office |

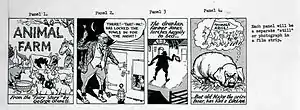

The IRD is most notable for being the government department to which George Orwell submitted his list of suspected communists (Orwell's list), including many notable people such as Charlie Chaplin, Paul Robeson, and Michael Redgrave. With the help of Orwell's widow Sonia Orwell and his former publisher Fredric Warburg, the IRD gained the foreign rights to much of Orwell's work and spent years distributing Animal Farm onto every continent, translating Orwell's works into 20 different languages,[6] funding the creation of an Animal Farm cartoon,[7] and working with the CIA to create the feature-length Animal Farm animated movie, the first of its kind in British history.[8] Many historians have noted how Orwell's literary reputation can largely be credited to joint propaganda operations between the IRD and CIA.[9] The IRD heavily marketed Animal Farm for audiences in the middle-east in an attempt to sway Arab nationalism and independence activists from seeking Soviet aid, as it was believed by IRD agents that a story featuring pigs as the villains would appeal highly towards Muslim audiences.[10] The IRD funded the activities of many authors including Arthur Koestler, Bertrand Russell, and Robert Conquest.

Internationally, IRD agents took part in many historic events, including Britain's entry into the European Economic Community,[11] the Korean War,[11] the Suez Crisis,[12] the Malayan Emergency,[13]The Troubles,[5] the Mau Mau Uprising,[14] Cyprus Emergency,[15] and the Sino-Indian War.[16][17] Other IRD activities included forging letters and posters,[1] attempting to bribe MPs,[18] conducting smear attacks against British trade unionists, and attacking opponents of the British military by planting fake news stories in the British press. Some of these fabricated stories the IRD created included accusations that Irish republicans were killing dogs by setting them on fire,[5] and falsely accusing EOKA members of raping schoolgirls.[19]

Although the existence of the IRD was successfully kept hidden from the British public until the 1970s, the Soviet Union had always been aware of its existence as Guy Burgess had been posted to IRD for a period of two months in 1948.[20] Burgess was later sacked by the IRD's founder Christopher Mayhew, who accused him of being "dirty, drunk and idle."[21] The IRD closed its operations in 1977 after its existence was discovered by British journalists after an investigation into a heavy amount of anti-Soviet propaganda being published by academics belonging to St Antony's College, Oxford.[22] An expose published in the Guardian titled by David Leigh "Death of the Department that Never Was", became the first public acknowledgement of the IRD's existence.[23]

Origins

Since 1946, many senior officials of both the Foreign Office and the Labour Party had proposed the creation of an anti-communist propaganda organ. Christopher Warner raised a formal proposal in April 1946, but Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Ernest Bevin was reluctant to upset the pro-Soviet members of the Labour Party. Later in the summer, Bevin rejected another proposal by Ivone Kirkpatrick to set up an anti-communist propaganda unit.[26] In 1947, Christopher Mayhew lobbied for the proposals, linking anti-communism with the concept of "Third Force", which was meant to be a progressive camp between the Soviet Union and the United States. This framing, together with anti-British Soviet propaganda attacks during the same years, led Bevin to change his position and to start discussing the details for the creation of a propaganda unit.[27] After sending a confidential paper to the foreign secretary, Ernest Bevin, in 1947, Mayhew was summoned by Attlee to Chequers to discuss it further.[21]

On 8 January 1948, the Cabinet of the United Kingdom adopted the Future Foreign Publicity, memorandum drafted by Christopher Mayhew and signed by Ernest Bevin. The memorandum embraced anti-communism and took upon the British Labour Government to lead anti-communist progressivism internationally, stating:[28]

It is for us, as Europeans and as a Social Democratic Government, and not the Americans, to give the lead in spiritual, moral and political sphere to all the democratic elements in Western Europe which are anti-Communist and, at the same time, genuinely progressive and reformist, believing in freedom, planning and social justice—what one might call the ‘Third Force’.

To achieve these goals, the memorandum called for the establishment of a Foreign Office department "to collect information" about Communism and to "provide material for our anti-Communist publicity through our Missions and Information Services abroad". The department would collaborate with ministers, British delegates, the Labour Party, trade union representatives, the Central Office of Information, and the BBC Overseas Service.[29] The new department was finally established as the Information Research Department. Mayhew ran the department with Sir Ivone Kirkpatrick[21] until 1950. The original offices were in Carlton House Terrace, before moving to Riverwalk House, Millbank, London.[30]

Staff and collaborators

The IRD was once one of the largest and well-funded of the UK Foreign Office,[4] with an estimated 400-600 employees at its height.[1] Although the IRD was founded under Clement Attlee's post-WWII Labour Party government (1945-1951) the department has been headed by numerous different politicians of both the Labour Party and Conservative Party, including Ralph Murray, John Rennie, and Ray Whitney. Although the vast majority of IRD staff were white British men, the department also hired emigres from Iron Curtain countries, the most notable being rocket scientist Grigori Tokaty.[31] Other staffers of note include Robert Conquest, whose secretary Celia Kirwan collected Orwell's list.[32] Tracy Philipps was also based at the IRD, working to recruit emigres from Eastern Europe.[33] Many IRD agents were former members of Britain's WWII propaganda department, the Political Warfare Executive (PWE). This high level of PWE veterans within the IRD, coupled with the similarities between how these two propaganda departments operated, has led some historians to describe the department as a "peacetime PWE".[34]

Outside of full-time agents, many historians, writers, and academics were either paid directly to publish anti-communist propaganda by the IRD or whose works were bought and distributed by the department using British embassies to both translate and distribute their works across the globe. Some of these authors include George Orwell, Bertrand Russell, Arthur Koestler, Czesław Miłosz, Brian Crozier, Richard Crossman, Will Lawther, A. J. P. Taylor, Baron Wyatt of Weeford, Leonard Schapiro, Denis Healey, Douglas Hyde, Margarete Buber, Victor Kravchenko, W.N. Ewer, Victor Feather, and hundreds (possibly thousands) of others[35][36] Some authors such as Bertrand Russell was fully aware of the funding for their books, while others such as the philosopher Bryan Magee were outraged when they found out.

Bertrand Russell

As part of its remit "to collect and summarize reliable information about Soviet and communist misdoings, to disseminate it to friendly journalists, politicians, and trade unionists, and to support, financially and otherwise, anti-communist publications",[37] it subsidised the publication of books by 'Background Books', including three by Bertrand Russell: Why Communism Must Fail, What Is Freedom?, and What Is Democracy?[37] The IRD bulk ordered thousands of copies of Russell's books, most notably his work "Why Communism Must Fall, and worked with the United States government to distribute them using embassies as cover.[38] Working closely with the British Council, the IRD worked to build Russell's reputation as an anti-communist writer, and to use his works to project power overseas.[39][40]

.jpg.webp)

Arthur Koestler

Koestler enjoyed strong personal relationships with IRD agents from 1949 onwards and was supportive of the department's anti-communist goals.[41] Koestler's relationship with the British government was so strong that he had become a de facto advisor to British propagandists, urging them to create a popular series of anti-communist left-wing literature to rival the success of the Left Book Club.[42] In return for his services to British propaganda, the IRD awarded Koestler by purchasing 1,000s of copies of his book Darkness at Noon and distributed them throughout Germany.[43]

Propaganda

The IRD created, sponsored, and distributed a wide range of propaganda publications both fiction and non-fiction, in the form of books, magazines, pamphlets, newspaper articles, radio broadcasts, and cartoons. Books which the IRD believed could be used for British propaganda purposes were translated into dozens of languages and then distributed using British embassies. Most IRD material targeted the Soviet Union, but much of their work also attacked socialist and anti-colonial revolutionaries in Cyprus,[44] Malaya (now Malaysia),[45] Singapore,[42] Ireland,[46] Korea,[47] Egypt,[48] and Indonesia.[47] In Britain, the department used its propaganda to spread smear stories targeting trade union leaders and human rights activists, but was also used by the Labour Party to conduct internal purges against socialist members.[4]

British introductions to IRD were made discreetly, with journalists being told as little as possible about the department. Propaganda material was sent to their homes under plain cover as correspondence marked "personal" carried no departmental identification or reference. They were told documents were "prepared" in the FCO primarily for members of the diplomatic service, but that it was allowed to give them on a personal basis to a few people outside the service who might find them of interest. As such, they were not statements of official policy and should not be attributed to HMG, nor should the titles themselves be quoted in discussion or in print. The papers should not be shown to anyone else and they were to be destroyed when no longer needed.[21]

Animal Farm - George Orwell

George Orwell's Animal Farm was republished, distributed, translated, and promoted for many years by IRD agents. Of all the propaganda works ever supported by the IRD, Animal Farm was given more attention and support by IRD agents than any publication in the department's history and arguable given more support from the British and American governments than any other propaganda book in the entire history of the Cold War.[49] The IRD gained the translation rights to Animal Farm in Chinese, Danish, Dutch, French, German, Finnish, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Indonesian, Latvian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish, and Swedish.[24] The Chinese version of Animal Farm was created in a joint operation between British and American government propagandists, which also included a pictorial version.[25]

To further promote Animal Farm, the IRD commissioned cartoon strips to be planted in newspapers across the globe.[50] The foreign rights to distribute these cartoons were acquired by the IRD for Cyprus, Tanganyika, Kenya, Uganda, Northern and Southern Rhodesia, Nyasaland, Sierra Leone, Gold Coast, Nigeria, Trinidad, Jamaica, Fiji, British Guiana and British Honduras.[49]

Encounter magazine

In a joint operation with the CIA, Encounter magazine was established. Published in the United Kingdom, it was a largely Anglo-American intellectual and cultural journal, originally associated with the anti-Stalinist left, intended to counter the idea of cold war neutralism. The magazine was rarely critical of American foreign policy, but beyond this editors had considerable publishing freedom. It was edited by Stephen Spender from 1953 to 1966. Spender resigned after it emerged that the Congress for Cultural Freedom, which published the magazine, was being covertly funded by the CIA.[51]

Activities

Italy

In 1948, fearing a victory of the Italian Communist Party in the general election, the IRD instructed the Embassy of the United Kingdom in Rome to disseminate anti-communist propaganda. Ambassador Victor Mallet chaired a small ad hoc committee to circulate IRD propaganda material to anti-communist journalists and Italian Socialist Party and Christian Democracy politicians.[52]

Indonesia

Following the abortive Indonesian Communist coup attempt of 1965 and the subsequent reprisal killings, the IRD's South East Asia Monitoring Unit in Singapore assisted the Indonesian Army's destruction of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) by circulating anti-PKI propaganda through several radio channels including the British Broadcasting Corporation, Radio Malaysia, Radio Australia, and the Voice of America, and through newspapers like The Straits Times. The same anti-PKI message was repeated by an anti-Sukarno radio station called Radio Free Indonesia and the IRD's own newsletter. Recurrent themes emphasised by the IRD included the alleged brutality of PKI members in murdering the Indonesian generals and their families, Chinese intervention in the Communist attempt to overthrow the government, and the PKI subverting Indonesian on behalf of foreign powers. The IRD's propaganda efforts were aided by the United States, Australian and Malaysian governments which had an interest in supporting the Army's anti-Communist mass murder and opposing President Sukarno. The IRD's information efforts helped corroborate the Indonesia Army's propaganda efforts against the PKI. In addition, the Harold Wilson Labour Government and its Australian counterpart gave the Indonesian Army leadership an assurance that British and Commonwealth forces would not step up the Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation.[53]

British trade unions

In 1969 Home Secretary James Callaghan requested actions that would hinder the careers of two "politically motivated" trade unionists, Jack Jones of the Transport and General Workers Union and Hugh Scanlon of the Amalgamated Engineering Union. This issue was raised in the cabinet and further discussed with Secretary of State for Employment Barbara Castle. A plan for detrimental leaks to the media was placed in the IRD files, and the head of the IRD prepared a briefing paper. However, information about how this was effected has not been released under the thirty-year rule under a section of the Public Records Act permitting national security exemptions.[4]

Reuters

In 1969 Reuters agreed to open a reporting service in the Middle East as part of an IRD plan to influence the international media. To protect the reputation of Reuters, which may have been damaged if the funding from the British government became known, the BBC paid Reuters “enhanced subscriptions” for access to its news service and was in turn compensated by the British government for the extra expense. The BBC paid Reuters £350,000 over four years.[54]

Controversies

The ethical objection raised by IRD's critics was that the public did not know the source of the information and could therefore not make allowances for the possible bias. It differed thus from straightforward propaganda from the British point of view.[21] This was countered by saying that the information was given to those who were already sympathetic to democracy and the West, and who had arrived at these positions independently.

Unattributed use by authors

Some writers who worked for the IRD have since found to have used IRD material and presented it to the academic community as though it were their own work. Robert Conquest's book The Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the Thirties "drew heavily from IRD files",[55] and multiple volumes of Soviet history which Conquest edited had also contained IRD material presented as though it were his own independent research.[56]

David Barzilay, a historian, writer, and former Scotland Yard officer was also found to have included "large sections" of material created by the IRD, presenting it as though it were his own research.[57]

Norman Mackenzie, The Guardian

Alexander Cockburn, Foreword to John Reed’s Snowball’s Chance,

Orwell's List

The IRD became the subject of heavy controversy in the UK after it was revealed that George Orwell had given the department a list of 38 people he suspected of being secret communists or who had heavy socialist leanings.

The existence of Orwell's List, also known as Foreign Office File "FO/111/189", was made public in 1996. However, the exact names included on the list were not made public until 2003. The list came into possession of the IRD in 1949, after being collected by IRD agent Celia Kirwan. Kirwan was a close friend of Orwell, she was also Arthur Koestler's Sister-in-law and the secretary for fellow IRD agent Robert Conquest. The list itself was divided into three columns headed "Name" "Job" and "Remarks", and referred to those listed as "FTs" meaning Fellow Travelers, and labeled people he believed of being suspected of being secret Marxists as "cryptos". Some of the names listed by Orwell included filmmaker Charlie Chaplin, writer J. B. Priestley, actor Michael Redgrave, historian E. H. Carr, New Statesman editor Kingsley Martin, New York Times's Moscow correspondent Walter Duranty, historian Isaac Deutscher, Labour Party MP Tom Driberg and the novelist Naomi Mitchison, as well as other lesser-known writers and journalists. Only one of the people named by Orwell, Peter Smollett, was ever revealed to have been a real Soviet agent. Peter Smollett, who Orwell claimed "...gives strong impression of being some kind of Russian agent. Very slimy person." Smollett had been the head of the Soviet section in the British Ministry of Information, while in fact being a Soviet agent who had been recruited by Kim Philby.

Reactions to the knowledge that Orwell had acted as an informant for the British Empire have been mixed, with some people crediting Orwell's actions to mental illness, others labelling Orwell's List as a "snitch list",[58] and some writers theorising that Orwell's suspicion of numerous African, homosexual, and Jewish people within his list signified bigotry.[59] Academic Norman MacKenzie, who knew Orwell personally and considered him a friend, lived long enough to discover that Orwell had reported him to the British secret service on suspicion of being a secret communist. MacKenzie responded to learning that Orwell had reported him, and credited Orwell's actions to his degrading mental state caused by Tuberculosis.[60] Alexander Cockburn was far less sympathetic, labelling Orwell a "snitch" and a bigot for the information included in Orwell's notebook, another list of suspected communists that came into the possession of the IRD. This notebook created by Orwell which contained 135 names, was also found to have been held by the Foreign Office. Within this document, Orwell describes African-American Civil Rights leader Paul Robeson as a "very anti-white...U.S Negro".[61]

Fabricated rape and pedophilia allegations

During the Cyprus Emergency, IRD agents used newspaper journalists to spread fabricated stories that guerrillas belonging to the National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA), had raped schoolgirls. These propaganda stories were manufactured as a part of 'Operation TEA-PARTY', a black propaganda operation in which IRD agents created pamphlets accusing EOKA guerrillas of forcing schoolgirls to have sex with them, and alleging that the youngest of these schoolgirls was 12 years old.[15] Among other fabricated stories, IRD agents attempted to convince American journalists that EOKA had links to communism in an attempt to gain American support, citing "secret documents" and "classified intelligence reports" which said journalists were never allowed to view.[15]

Discovery and closure

The department was said to be closed down by then Foreign Secretary, David Owen, in 1977. Its existence did not become public until 1978.[21][4]

See also

References

- Berg, Sanchia (18 March 2019). "'Fake news' sent out by government department". BBC. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Sinclair, Ian (2021). "The original 'fake news'? The BBC and the Information Research Department". The Morning Star. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Wilford, Hugh (1998). "The Information Research Department: Britain's Secret Cold War Weapon Revealed". Review of International Studies. 24: 366 – via JSTORE.

- Cobain, Ian (24 July 2018). "Wilson government used secret unit to smear union leaders". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Rory, Cormac (6 December 2016). "The Information Research Department, Unattributable Propaganda, and Northern Ireland, 1971-1973: Promising Salvation but Ending in Failure?". English Historical Review. 131 (552): 1094.

- Rubin N., Andrew (2012). Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War. Woodstock: Princeton University Press. pp. 40–42.

- Dunton, Mark (17 August 2020). "Animal Farm: The cartoon strip and the Cold War". National Archives. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Shaw, Tony (22 September 2011). "Making a pig's ear of Orwell". The Independent. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Mitter, Rana; Major, Patrick (2005). Across the Block: Cold War Cultural and Social History. Taylor & Francis e-library: Frank Cass and Company Limited. p. 125.

- Jeffreys-Jones, Rhodri (2013). In Spies we Trust: The story of Western Intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 145.

- Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. E-book version: Routledge. p. 4.

- Lashmar, Paul; Oliver, James (1988). Britain’s Secret Propaganda War 1948-1977. Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing. p. 68.

- Blotch, Jonathan; Fitzgerald, Patrick (1983). British Intelligence and Covert Action: Africa, Middle-East and Europe since 1945. London: Junction Books. p. 93.

- Lashmar, Paul (1988). Britain’s Secret Propaganda War 1948-1977. Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing. p. 88.

- Dorril, Stephen (2002). MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service. New York: Touchstone. p. 552.

- McGarr, Paul M. (24 November 2017). "The Information Research Department, British covert propaganda, and the Sino-Indian War of 1962: combating communism and courting failure?". International History Review. 41 (1). doi:10.1080/07075332.2017.1402070. ISSN 0707-5332.

- Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. eBook version: Routledge. p. 17.

- Lucas, Scott (22 October 2011). "REAR WINDOW : COLD WAR :The British Ministry of Propaganda". The Independent. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Dorril, Stephen (2002). MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service. New York: Touchstone. p. 552.

- Lashmar, Paul; Oliver, James (1988). Britain’s Secret Propaganda War 1948-1977. Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing. pp. 37–38.

- Death of the department that never was from The Guardian, 27 January 1978

- Lashmar, Paul (1988). Britain’s Secret Propaganda War 1948-1977. UK, Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing. p. 1.

- Leigh, David (27 January 1978). "Death of the department that never was" (PDF). The Guardian. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Rubin, Andrew N. (2012). Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War. Woodstock: Princeton University Press. p. 40.

- Mitter, Rana (2005). Across the Block: Cold War Cultural and Social History. Taylor & Francis e-library: Frank and Cass Company Limited. p. 117.

- Wilford 1998, p. 355.

- Wilford 1998, pp. 355-356.

- Wilford 1998, p. 356.

- Wilford 1998, pp. 356-357.

- Lashmar, Paul (1988). Britain’s Secret Propaganda War 1948-1977. Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing. p. 30.

- "Professor Grigori Tokaty". The Independent. 25 November 2003. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- D J Taylor (6 November 2002). "Obituary: Celia Goodman". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Kirby, Dianne (2000). "Christian Faith, Communist Faith: Some Aspects of the Relationship between the Foreign Office Information Research Department and the Church of England Council on Foreign Relations, 1950-1953". Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte. 13 (1): 227–228. JSTOR 43750890.

- Cull, Nicholas J.; Culbert, David; Welch, David (2003). Propaganda and Mass Persuasion. Oxford: ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 152.

- Defty, Andrew (2005). America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. eBook version: Routledge. p. 87.

- Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. eBook version: Routledge. p. 259.

- "Orwell's List" by Timothy Garton Ash. The New York Review of Books Volume 50, Number 14. 25 September 2003

- Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. eBook version: Routledge. p. 172.

- Rubin, Andrew N. (2012). Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War. Woodstock: Princeton University Press. p. 37.

- Jenks, John (2006). British Propaganda and News Media in the Cold War. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 70.

- Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. eBook version: Routledge. p. 87.

- Jenks, John (2006). British Propaganda and News Media in the Cold War. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 64.

- Wilford, Hugh (2013). The CIA, the British Left and the Cold War: Calling the Tune?. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 58.

- Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. eBook version: Routledge. p. 10.

- Rubin, Andrew N. (2012). Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War. Woodstock: Woodstock: Princeton University Press. p. 34.

- Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. eBook version: Routledge. p. 3.

- Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. eBook version: Routledge. p. 4.

- Rubin, Andrew N. (2012). Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War. Woodstock: Princeton University Press. p. 88.

- Mitter, Rana (2005). Across the Block: Cold War Cultural and Social History. Taylor & Francis e-library: Frank Cass and Company Limited. p. 117.

- Defty, Andrew (2005). Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-1953: The Information Research Department. e-book version: Routledge. p. 161.

- Frances Stonor Saunders (12 July 1999), "How the CIA plotted against us", New Statesman, archived from the original on 10 October 2014

- Wilford 1998, pp. 358-359.

- Easter, David (2005). "Keep the Indonesian Pot Boiling: Western Covert Intervention in Indonesia, October 1965—March 1966" (PDF). Cold War History. 5 (1): 64–65. doi:10.1080/1468274042000283144.

- Rosenbaum, Martin (13 January 2020). "How the UK secretly funded a Middle East news agency". BBC. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Macdonald, Scot (2006). Propaganda and Information Warfare in the Twenty-First Century. Taylor & Francis e-library: Taylor & Francis. p. 47.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (2017). Red Flag Unfurled: History, Historians, and the Russian Revolution. London: Verso. p. 94. ISBN 978-1784785642.

- Lashmar, Paul; Oliver, James (1988). Britain’s Secret Propaganda War 1948-1977. Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing. p. 161. ISBN 978-0750916684.

- Norton, Ben (14 December 2016). "George Orwell was a reactionary snitch who made a blacklist of leftists for the British government". bennorton.com. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Cockburn, Alexander (28 August 2012). "The Fable of the Weasel". Melville House Publications. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Gibbons, Fiachra (24 June 2003). "Blacklisted writer says illness clouded Orwell's judgement: Survivor tells Guardian that author was 'losing his grip'". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Rubin, Andrew (2012). Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War. Woodstock: Princeton University Press. p. 29.